|

by

Kate Golembiewski

October 16,

2020

from

EurekAlert Website

Spanish

version

Italian

version

The ruins of the Roman Forum,

once a

site of a representational government.

Credit: (c) Linda Nicholas, Field Museum

The

world has never seen a Technocracy, but all previous

civilizations and governmental systems have come and

gone.

Accordingly, the United States and its Constitutional

Republic of government is in its sunset phase unless its

citizenry can resuscitate it.

Source

History shows

that societies

collapse

when leaders

undermine social contracts...

All good things must come to an end.

Whether societies are

ruled by ruthless dictators or more well-meaning representatives,

they fall apart in time, with different degrees of severity.

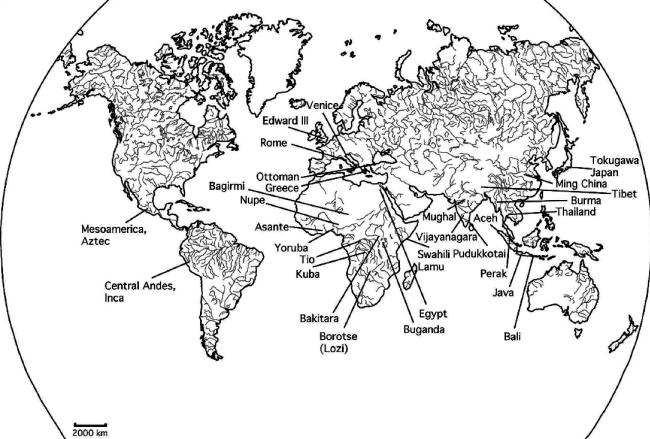

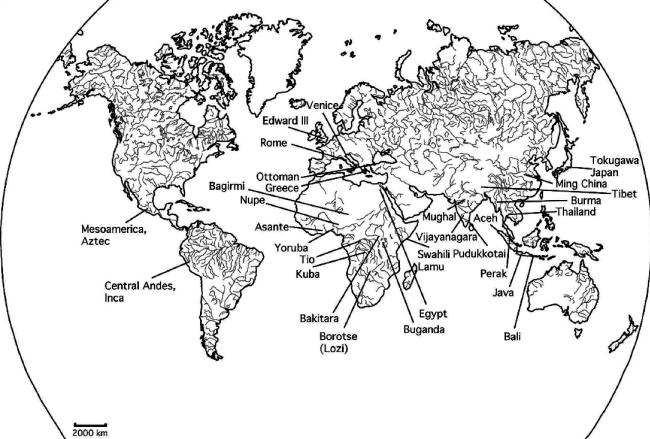

In a new paper (Moral

Collapse and State Failure - A View from the Past - here

too), anthropologists examined a

broad, global sample of 30 pre-modern societies.

They found that when

"good" governments - ones that provided goods and services for their

people and did not starkly concentrate wealth and power - fell

apart, they broke down more intensely than collapsing despotic

regimes.

And the researchers found

a common thread in the collapse of good governments:

leaders who

undermined and broke from upholding core societal principles,

morals, and ideals.

"Pre-modern

states were not that different from modern ones.

Some pre-modern

states had good governance and weren't that different from

what we see in some democratic countries today," says Gary

Feinman, the MacArthur curator of anthropology at Chicago's

Field Museum and one of the authors of a new study in

Frontiers in Political Science.

"The states that

had good governance, although they may have been able to

sustain themselves slightly longer than autocratic-run ones,

tended to collapse more thoroughly, more severely."

"We noted the potential for failure caused by an internal

factor that might have been manageable if properly

anticipated," says Richard Blanton, a professor emeritus of

anthropology at Purdue University and the study's lead

author.

"We refer to an

inexplicable failure of the principal leadership to uphold

values and norms that had long guided the actions of

previous leaders, followed by a subsequent loss of citizen

confidence in the leadership and government and collapse."

In their study (PDF),

Richard Blanton, Gary Feinman, and their colleagues

took an in-depth look at the governments of four societies:

-

the Roman Empire

-

China's Ming

Dynasty

-

India's Mughal

Empire

-

the Venetian

Republic

Source

These societies

flourished hundreds (or in ancient Rome's case, thousands) of years

ago, and they had comparatively more equitable distributions of

power and wealth than many of the other cases examined, although

they looked different from what we consider "good governments" today

as they did not have 'popular elections'...

"There were basically

no electoral democracies before modern times, so if you want to

compare good governance in the present with good governance in

the past, you can't really measure it by the role of elections,

so important in contemporary 'democracies'...

You have to come up

with some other yardsticks, and the core features of the good

governance concept serve as a suitable measure of that," says

Feinman.

"They didn't have

elections, but they had other checks and balances on the

concentration of personal power and wealth by a few individuals.

They all had means to

enhance social well-being, provision goods and services beyond

just a narrow few, and means for commoners to express their

voices."

In societies that meet

the academic definition of "good governance," the government meets

the needs of the people, in large part because the government

depends on those people for the taxes and resources

that keep the state afloat.

"These systems

depended heavily on the local population for a good chunk of

their resources.

Even if you don't

have elections, the government has to be at least somewhat

responsive to the local population, because that's what funds

the government," explains Feinman.

"There are often

checks on both the power and the economic selfishness of

leaders, so they can't hoard all the wealth."

Societies with good

governance tend to last a bit longer than autocratic governments

that keep power concentrated to one person or small group.

But the flip side of that

coin is that when a "good" government collapses, things tend to be

harder for the citizens, because they'd come to rely on the

infrastructure of that government in their day-to-day life.

"With good

governance, you have infrastructures for communication and

bureaucracies to collect taxes, sustain services, and distribute

public goods. You have an economy that jointly sustains the

people and funds the government," says Feinman.

"And so social

networks and institutions become highly connected, economically,

socially, and politically.

Whereas if an

autocratic regime collapses, you might see a different leader or

you might see a different capital, but it doesn't permeate all

the way down into people's lives, as such rulers generally

monopolize resources and fund their regimes in ways less

dependent on local production or broad-based taxation."

The researchers also

examined a common factor in the collapse of societies with good

governance:

leaders who abandoned

the society's founding principles and ignored their roles as

moral guides for their people.

"In a good

governance society, a moral leader is one who upholds the

core principles and ethos and creeds and values of the

overall society," says Feinman.

"Most societies

have some kind of social contract, whether that's written

out or not, and if you have a leader who breaks those

principles, then people lose trust, diminish their

willingness to pay taxes, move away, or take other steps

that undercut the fiscal health of the polity."

This pattern of amoral

leaders destabilizing their societies goes way back:

the paper uses

the Roman Empire as an example...

The Roman emperor

Commodus inherited a state with

economic and military instability, and he didn't rise to the

occasion; instead, he was more interested in performing as a

gladiator and identifying himself with Hercules.

He was eventually

assassinated, and the empire descended into a period of crisis and

corruption.

These patterns can be

seen today, as

corrupt or inept leaders threaten

the core principles and, hence, the stability of the places they

govern:

...are all evidenced in

democratic nations today.

"What I see around me

feels like what I've observed in studying the deep histories of

other world regions, and now I'm living it in my own life," says

Feinman.

"It's sort of like

Groundhog Day for archaeologists and historians."

"Our findings provide insights that should be of value in the

present, most notably that societies, even ones that are well

governed, prosperous, and highly regarded by most citizens, are

fragile human constructs that can fail," says Blanton.

"In the cases we

address, calamity could very likely have been avoided, yet,

citizens and state-builders too willingly assumed that their

leadership will feel an obligation to do as expected for the

benefit of society.

Given the failure to

anticipate, the kinds of institutional guardrails required to

minimize the consequences of moral failure were inadequate."

But, notes Feinman,

learning about what led to societies collapsing in the past can help

us make better choices now:

"History has a chance

to tell us something.

That doesn't mean

it's going to repeat exactly, but it tends to rhyme. And so that

means there are lessons in these situations."

|