|

by Paul Cudenec

September 14, 2024

from

WinterOak Website

For readers primarily interested in my political writing, this

current exploration of the sophiological tradition via

the pages of

The Heavenly Country might not

seem terribly relevant.

But in fact the ideas I have been discussing here are of fundamental

importance for the building of our New Resistance against the

criminocracy.

Their pertinence to the great struggle ahead of us is, indeed,

expressed time after time in the pages of the book.

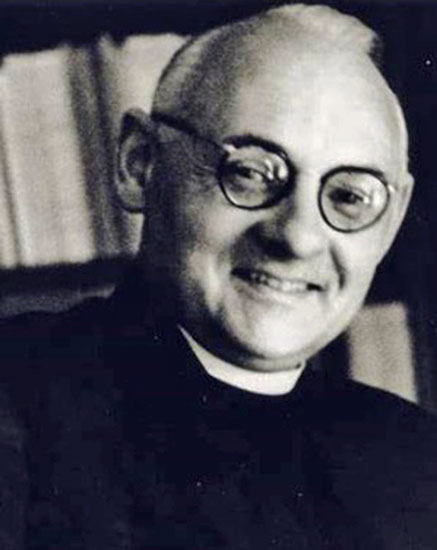

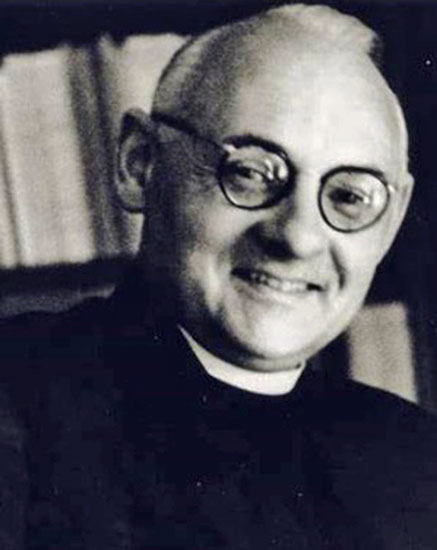

Editor Michael Martin (pictured) declares in the

introduction:

"We live in an age of untrammeled

superstition:

the hope that science will save us from

ourselves and bless us with prosperity and, even, that it

will allow us to overcome death.

"This is an age of the totalization of the

technological and

the technocratic, an age of the

unreal, the artificial, the illusory, of the simulacra". 1

"In this paradigm, the human person is viewed as a machine among

other machines, replete with updateable hardware, a myriad

number of applications, and the promise of replaceable as well

as changeable parts. I, human, iHuman...

"Accepting the human person as a machine ultimately distances

the human person from himself, from the awareness of himself as

a human person, as an integrally somatic, pneumatological and

existential being.

"Yet it is the machine model (though few have the

courage to name it as such) that is ascendant in our own

cultural moment.

"We see this perhaps most clearly in the burgeoning gender

reassignment industry, an industry not only of technological

application, but also now fully integrated into the political,

corporate, and entertainment complex". 2

Martin describes a long-term project of control

and transformation of matter that was initially directed outwardly

towards the exploitation of nature and the colonization of peoples.

He adds:

"It has now been turned onto the human

subject himself, oftentimes with individuals allowing their own

bodies to be colonized by the totalizing dictates of ideology".

3

Several ideas about how this historical process

started and developed are advanced by authors featured in the book.

Artur Sebastian Rosman sees a seed in certain kinds of

Protestant thinking, in which,

"God's transcendence of creation is

accentuated so as to almost form a complete break". 4

The poet Novalis, in his 1799 essay

'Christendom or Europe?', while acknowledging,

"the transitory blaze of heaven" in

Protestantism's beginnings, identifies a "corrosive influence"

which led us into an age in which "the worldly has gained the

upper hand". 5

He states:

"The history of Protestantism shows us no

great and splendid manifestations of the supernatural any more"

6 and argues that hatred of the Catholic Church had

gradually extended into hatred of the Christian faith, of

religion in general and then of

"all objects of enthusiasm".

"It made imagination and emotion heretical, as well as morality

and the love of art, the future and the past.

With some difficulty it placed man first in

the order of created things, and reduced the infinite creative

music of the universe to the monotonous clatter of a monstrous

mill". 7

Novalis (pictured) depicts thinkers of the

Enlightenment as,

"tirelessly busy cleaning the poetry of

Nature, the earth, the human soul, and the branches of learning

- obliterating every trace of the holy, discrediting by sarcasm

the memory of all ennobling events and persons, and stripping

the world of all colorful ornament". 8

The flat and rigid thinking regarded as

"scientific" came to dominate our society, as Brent Dean Robbins

explains in his essay.

"In our technological world, the call

of the natural world, can get drowned out by the abstract

theoretical concepts that have increasingly come to replace our

receptivity to the concrete claims of the phenomena that compose

our life-world". 9

He says the Cartesian-Newtonian view, what

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe calls,

"the gloom of the

empirico-mechanico-dogmatic torture chamber", 10

...understands the world through a veil of

mathematics and regards human perception as untrustworthy.

"It performs, in other words, what

philosophers have come to call 'reductionism':

it comes to explain the world of human

experience by 'reducing' its meaning to causal events

'behind' the phenomena.

"For example, what you see are colors; but,

in reality, there are 'nothing but' waves of light.

Reductionism, in this sense, is the

disease of 'nothing-but-ness'.

'Nothing-but-ness' is another term for

nihilism". 11

A similar conclusion is reached by Bruce V.

Foltz, who argues that,

"we have a monstrous distortion of creation:

nature as something bereft of divinity

and grace... leaving qualities such as goodness and beauty

merely subjective labels". 12

Analyzing the work of novelist Fyodor

Dostoevsky, he identifies a series of,

"unhappy, disappointed, Westernized

intellectuals" in his fiction.

"These are figures whose hearts have been corrupted by their

thoughts and by their attachment to their thoughts, and for whom

created nature is an object of contempt (the battered and bitter

Underground Man, for whom it is a realm of dumb necessity) or

revulsion (Raskolnikov, who from within the Hell of his own

making experiences nature as scorching and sulfuric, i.e., as

itself infernal).

"These are nihilistic figures... cerebral, disembodied figures

(shades, perhaps) believing only in the reign of the Man-God,

humanity elevating itself to the status of world-creator".

13

Some go further than labeling this phenomenon

merely nihilistic.

Foltz points to Sergei Bulgakov's concept of a,

"diabolical economy... obscuring and debasing

and disfiguring original creation". 14

And The Heavenly Country editor Martin

evokes the powerful critique of modernity voiced by 20th

century Welsh poet David Jones.

"Like Heidegger, Steiner, Huxley, and so many

others who have raised concerns about the human, cultural, and

spiritual costs of our infatuation with technology, Jones argues

that we have made this technology into an idol, a

Moloch-like demon he calls

the Ram, and that this god demands the

instrumentalization and subsequent sacrifice of human persons".

15

Martin describes Jones',

"condemnation of the anti-sophiology that

rules modernity, a modernity that can no longer recognize what a

human person is, what gender is, what marriage is or what is

real".

And he remarks:

"This is truly a modernity in which 'dead

forms multiply' and it is characterized by the fetishization of

sterility". 16

He also reminds us of Nikolai Berdyaev's

1935 warning that,

"the world threatens to become an organized

and technicized chaos in which only the most terrible forms of

idolatry and demon-worship can live".

And he adds,

"That day is here"... 17

So,

how are we to bring down the demon Moloch and

the modern techno-hell in which he has enslaved us?

Reviving and popularizing the natural-spiritual

perspective offered by sophiology could well be part of the answer.

Martin says his book,

"provides an antidote to the ontological

poison with which we have all been infected" 18 and

presents "a worldview that can heal the ontological,

teleological and epistemological wounds from which our age so

deeply suffers". 19

But the figure of

Sophia can also act as a dynamic

factor in our own relationships with existence, offering us guidance

on the path to what Foltz terms Katharsis (purification of the

heart) and a subsequent metanoia (change of heart) that would

allow us to experience the sacred presence in nature and in others.

20

He insists:

"Only when we apprehend nature as divinely

instituted, i.e., see it as creation, are we able to learn from

it, to sense the divine wisdom interwoven throughout it.

"That is, only by means of askesis (understood not

primarily as fasting and vigils, but purification of the heart)

can nature be seen deeply and the divine wisdom reigning within

it be revealed". 21

To reach this understanding, this gnosis, we need

to be open to inspiration, writes 20th century theologian

Hans Urs von Balthasar (pictured),

"a moment when the 'spirit that contains the

god' (en-thusiasmos) obeys a superior command which as such

implies form and is able to impose form". 22

"Such creative form, then, is God's work, and the work of man

only in so far as he makes himself available to the divine

action without opposition, allowing God to act, concurring in

his work.

"Such 'art' becomes visible in the Christian sphere in

the life-forms of the chosen.

In its exact sense, prophetic existence is

the existence of a person who in faith has been divested of any

intent to give himself shape, who makes himself available as

matter for the divine action". 23

The divine action for which we all need to make

ourselves available is that of fighting the evil of the dark

enslaving empire that today dominates our society.

And the potential role of Sophia in inspiring us in this task is

portrayed in the words of the 17th century English mystic

Jane Lead, whose visionary encounter with "God's Eternal

Virgin-Wisdom" is described in the first of these essays.

Sophia warns of,

"the Dragon and the Beast, with all his

horned power... which the whole World hath worshipped and

admired".

This vile entity,

"hath long had his Time, to impose strange

Laws, and Injunctions and hath been in Universally obeyed".

Sophia declares that,

"Sorceries, Witchcrafts, and Deceits have

worn out many Generations, who was ignorant of the Depths of

this subtle Serpent" and have tricked them into accepting "this

false usurped Power and Authority". 24

Sounds familiar...!

But she tells Lead:

"Be of good comfort, the Judge is nominated,

the Jury is chosen, by whom the Verdict will be given; therefore

be true to the Interest of my Son, who is appointed to judge the

World in thee, and to cast out Hell, Sin and Death, the Beast

and his retinue into the Lake, where there shall be no return

out thence, to assault thee with their Dregs and Poisonous

Floods.

"This is to be done by joining Issue and Power with me, whom am

come to help thee against the great Leviathan, who makes war

most, where he sees his Time of Reigning is almost worn out, and

that he must have no more place". 25

There is a definite compatibility between all

this and my own version of Sophia, whom I introduced in the opening

essay.

I present here

The Green One's concluding

statement as a parting encouragement, ahead of the completing

footnote to this three/four-part series.

"I have been called to action and will not

cease from mental fight.

I ride into battle,

-

as Tammuz and Pachamama

-

as Great Pan and Grandmother Spider

-

as Brigid and Jack in the Green

-

as Diana and Dikaiosune

-

as Joan of Arc and the Queen of

Elphame

-

as Cybele and Dionysus

-

as Oshún and Oannes

-

as Dodola and Jarilo

-

as viriditas and asha...

"And I ride into battle as much more than

these.

I am not just the sum of their parts, but the

understanding of how they all represent the same vital force

emerging through the human mind - the understanding, too, that

this understanding is important and that it is itself part of

the eternal wisdom of humanity, the Sophia Perennis.

"I am Sophia Perennis in active mode, in revolutionary mode, in

the mode of destroying all that stands in the way of my

reinstatement as the foundation of your thinking and your

living.

"I am your determination to ditch the dead-souled industrial

mindset that blocks your future". 26

References

-

Michael Martin, 'Introduction: Sophiology:

Genealogy and Phenomenon', in

The Heavenly Country - An Anthology of

Primary Sources, Poetry, and Critical Essays on Sophiology,

edited by Michael Martin (Kettering, Ohio: Angelico

Press/Sophia Perennis, 2016), p. 1.

-

Ibid.

-

Martin, 'Introduction', in The Heavenly

Country, p. 2.

-

Artur Sebastian Rosman, 'The Catholic

Imagination: A Sophiology Between Scatology and

Eschatology', in The Heavenly Country, p. 380.

-

Novalis, 'Christendom or Europe?', in The

Heavenly Country, p. 91.

-

Ibid.

-

Novalis, 'Christendom or Europe?', in The

Heavenly Country, p. 93.

-

Novalis, 'Christendom or Europe?', in The

Heavenly Country, p. 94.

-

Brent Dean Robbins, 'New Organs of

Perception: Goethean Science as a Cultural Therapeutics', in

The Heavenly Country, p. 325.

-

Quoted in Erich Heller, The Disinherited

Mind: Essays in Modern German Literature and Thought

(Cambridge: Bowes and Bowes, 1952), p. 18, cit. Robbins,

'New Organs of Perception', in The Heavenly Country, p. 319.

-

Robbins, 'New Organs of Perception', in

The Heavenly Country, pp. 316-17.

-

Bruce V. Foltz, 'Nature and Divine

Wisdom: How (Not) to Speak of Sophia', in The Heavenly

Country, p. 359.

-

Foltz, 'Nature and Divine Wisdom', in The

Heavenly Country, p. 356.

-

Foltz, 'Nature and Divine Wisdom', in The

Heavenly Country, p. 374.

-

Michael Martin, 'The Poetic of Sophia',

in The Heavenly Country, p. 400.

-

Martin, 'The Poetic of Sophia', in The

Heavenly Country, p. 401.

-

Nicolas Berdyaev, The Fate of Man in the

Modern World, trans. Donald A. Lowine (1935, reprt. Ann

Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan Press, 1961), p.

127, cit. etc Martin, 'The Poetic of Sophia', in The

Heavenly Country, p. 388.

-

Martin, 'Introduction', in The Heavenly

Country, p. 2.

-

Martin, 'Introduction', in The Heavenly

Country, p. 5.

-

Foltz, 'Nature and Divine Wisdom', in The

Heavenly Country, p. 356.

-

oltz, 'Nature and Divine Wisdom', in The

Heavenly Country, p. 363.

-

Hans Urs von Balthasar, 'The Glory of the

Lord: Volume 1: Seeing the Form', in The Heavenly Country,

p. 138.

-

bid.

-

Jane Lead, 'A Fountain of Gardens', in

The Heavenly Country, p. 79.

-

Jane Lead, A Fountain of Gardens, p. 78.

-

Paul Cudenec,

The Green One (Sussex,

Winter Oak, 2017), pp. 185-86.

|