|

by Jason Crawford

from the book 'The Techno-Humanist Manifesto' by Jason Crawford, Founder of the Roots of Progress Institute.

Introduction - The Present Crisis Never has humanity been so powerful, and at the same time so distrustful of our power. We live in an age of wonders.

To our ancient ancestors, our mundane routines would seem like wizardry:

We build our homes in towers that rise above the hills; we build our ships larger and stronger than the ocean waves; we build our bridges with skeletons of steel, to withstand wind and storm.

Our sages gaze deep into the universe, viewing colors the eye cannot see, and,

Once, these accomplishments, and their benefits

to humanity, were referred to simply as "progress."

In Guns, Germs, and Steel, a grand narrative of civilizational advancement, author Jared Diamond disclaims the assumption,

Diamond also called agriculture,

Historian Christopher Lasch is even less charitable, asking:

Economic growth is called an "addiction," a "fetish," a "Ponzi scheme," a "fairy tale." 6

There is even a "degrowth" movement advocating

economic regress as an ideal. 7

A 2015 survey of several Western countries found that only a small minority think that,

Another survey found that almost 20% of Americans think it was better to be born 200 years ago than today (with another 41% "not sure"). 11

Nor are people hopeful for improvement.

In 2023, over three quarters of Americans did not believe that life for their children would be better than their own, and only 24% were optimistic about the country's future. 11

Most worrying is that young people are particularly pessimistic:

With so little awareness of progress, and so much despair for the future, our society is unable to imagine what to build or to dream of where to go.

As late as the 1960s, Americans envisioned flying cars, Moon bases, and making the desert bloom using cheap, abundant energy from nuclear power. We might criticize some pieces of this vision, but at least they had a vision.

Today we hope, at best, to avoid disaster:

by a coalition of power companies

in the LA

Times, 1959. 13 This is not merely academic.

If society believes that scientific, technological and industrial progress is harmful or dangerous, people will work to slow it down or stop it

Activists have obstructed all forms of energy - nuclear power, oil and gas, even solar and wind 14 - and the average American benefits from no more energy today than fifty years ago. 15

The EU has largely banned the cultivation of GMOs,16 and opposition to Vitamin-enhanced "Golden Rice" has prevented it from

Sri Lanka created a food crisis for itself when it banned synthetic fertilizer in a hasty, bungled shift to "organic" farming. 18

In medicine, romantic notions of "natural" health

cause patients to shun treatment for cancer and vaccines for

diseases; measles outbreaks are now on the rise. 19

In the Middle Ages, guilds limited competition and resisted the introduction of new techniques. 20

In the Industrial Revolution, textile workers smashed and burned the machinery that threatened their jobs. 21

The first locomotives were opposed based on fears that they could never be made safe - an objection that was stressed by their competitors who operated wagon-roads and canals. 22

The first bicycles raised pseudo-medical concerns about damage to the spine and moral panic about ladies traveling unchaperoned. 23 Today, NIMBYs fight any housing development that would alter their "neighborhood character" or threaten their property values by expanding supply.

Progress needs principled defenders against the status quo.

And more:

Science, technology, and the economy require continual investment, and each new generation must receive and carry the torch.

Inventors and entrepreneurs of the Industrial Revolution were motivated by the power of steam and all that it could be applied to; those of the late 19th century were enthralled by electricity; the scientists and engineers in the late 20th century who went to NASA had grown up on Star Trek.

If we are to make progress today, it will be driven by technologists who are fascinated with the potential for technologies such as artificial intelligence or genetic engineering.

The defeatism that arose in the 20th century about the challenges of progress does not give us a way forward.

We need a new philosophy of progress for the 21st

century, and beyond. The time for that philosophy is now. Stagnation

and sclerosis have become too painful to ignore.

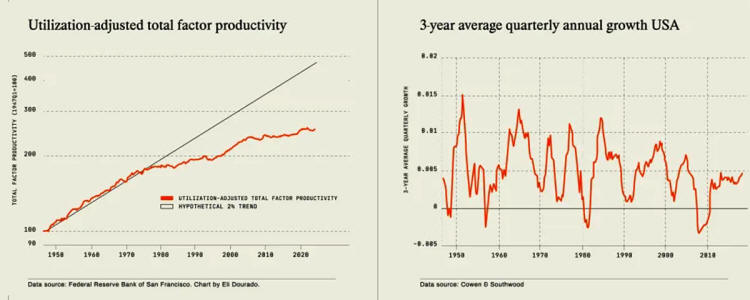

Manufacturing, construction, transportation, and energy have seen no new general-purpose technologies since the 1960s - contrast with the period 1880-1940, which saw the invention of electrical power, synthetic plastics, the assembly line, the automobile and the airplane.

The Concorde was grounded, and the planes we fly today actually go a bit slower than the jets of the 1960s. 26

The Apollo program was canceled; no human has left low-Earth orbit since 1972. 27

Eli Dourado,29

Cowen and

Southwood28

The costs of healthcare, education, and housing continue to rise. 30 Energy projects, even "clean" ones, are held up for years by permitting delays and lack of grid connections. 31

California's high-speed rail, now decades in the making, has already cost billions of dollars and is still years away from completing even an initial operating segment, which will not provide service to either LA or San Francisco. 32

During the covid 'pandemic', when speed was at a

premium, testing kits were delayed by the FDA, the NIH was still

taking months to approve research grants, and vaccine distribution

was hampered by squabbling over equity. 33

SpaceX is landing reusable rockets, promising to enable the space economy, and testing an enormous Starship, promising to colonize Mars

A new generation of founders have ambitions in atoms, not just bits: manufacturing facilities in space, net-zero hydrocarbons synthesized with solar or nuclear power, robots that carve sculptures in marble. 35

Most significantly, LLMs have created a general kind of artificial intelligence - which, depending on who you ask, is either the next big thing in the software industry, the next general-purpose technology to rival the steam engine or the electric generator, the next age of humanity after agriculture and industrialization, or the next dominant species that will replace humanity altogether.

All together, these developments promise to re-accelerate economic growth, but also raise fears ranging from technological unemployment to literal human extinction.

of Monumental Labs

Many of them feel they have become the scapegoat

for society's problems, from teen suicides to San Francisco housing

prices to the erosion of democracy. They have grown tired of playing

defense, and are going on the offense.

The optimists point out, correctly, that history is full of scaremongering and moral panics about technology that look downright silly in retrospect, and that on the whole, technology has been massively beneficial for humanity. 36

But being too dismissive of risk is a mistake, and it will backfire.

The risks are real - history provides many examples of them, in addition to the moral panics - and the public is too sensitive to them to accept any message that feels cavalier. Progress consists not of ignoring problems, but of embracing and solving them.

The right message is not "don't worry!" but,

Another, more philosophical response has been "accelerationism", which endorses progress as the inexorable unfolding of an evolutionary process.

This process is driven by the techno-capitalist machine, a "meta-organism" that tries to capture as much energy as possible for its own growth. 37

Accelerationists seek,

In practice, this means they are pro-technology and anti-regulation:

"Don't be afraid, just build." 39 This nascent movement projects energy, ambition, and positivity, and some tech founders and investors, including people I like and greatly respect, have adopted the label "effective accelerationist" (a play on the "effective altruists" who have been warning about existential risk from AI).

based in humanism and agency.

But as an ideological foundation for human flourishing, this philosophy points in the wrong direction. It emphasizes an impersonal process over individual lives.

Its stated goal is to "follow the 'will of the universe,'" or perhaps "to preserve the light of consciousness" 40 - but not your consciousness, necessarily, or mine.

And it denies that we have any real control over the process:

We are all merely agents of the machine.

The rest of this book will explain and defend

this idea.

I will clarify the idea of a humanistic standard of value and of human well-being itself. I will attempt to tease apart concepts such as happiness, life satisfaction, value-fulfillment, and self-actualization.

I include spiritual values in this idea of well-being (on a secular concept of the spiritual), and I will argue that material progress is in harmony with these values and even supports them.

And I will briefly address some of the costs and risks of progress, especially to health and safety, and give a framework for thinking about them.

In the future we should expect acceleration, not stagnation, because the progress of the past was not a fluke: problem-solving is fundamental to human nature.

I will conclude with an ambitious vision for the technological future.

I'll conclude with a brief description of the progress movement we need to accomplish this, and the changes in society it should bring about.

If you are in government or policy, I hope this book gives you a framework for thinking about your role and responsibility for providing a legal foundation for progress.

No matter who you are, I hope this book gives you a new and powerful way of thinking about the nature of human beings, our relationship to nature, and the role of science, technology and industry in human life. Above all, I want to inspire everyone who reads this to dream of a better future and to work in some way, small or large, to advance the grand project of human progress. References

|