|

by Nicole Martinelli

October 30, 2007

from

Wired Website

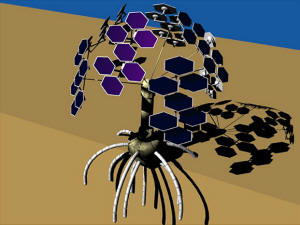

The "plantoid" is a

concept robot for exploring Mars.

Its roots would

explore the soil,

while power and

telecommunications are provided by the main stem and the solar

"leaves."

Image: Courtesy International Laboratory of Plant Neurobiology

SESTO FIORENTINO, Italy

Professor Stefano

Mancuso knows it isn't easy being green: He runs the world's

only laboratory dedicated to plant intelligence.

At the International Laboratory of Plant Neurobiology (LINV),

about seven miles outside Florence, Italy, Mancuso and his team of

nine work to debunk the myth that plants are low-life.

Research at the modern

building combines physiology, ecology and molecular biology.

"If you define

intelligence as the capacity to solve problems, plants have a

lot to teach us," says Mancuso, dressed in harmonizing shades of

his favorite color: green.

"Not only are they

'smart' in how they grow, adapt and thrive, they do it without

neuroses. Intelligence isn't only about having a brain."

Plants have never been

given their due in the order of things; they've usually been

dismissed as mere vegetables.

But there's a growing

body of research showing that plants have a lot to contribute in

fields as disparate as robotics and telecommunications. For

instance, current projects at the LINV include a plant-inspired

robot in development for the European Space Agency. The "plantoid"

might be used to

explore the Martian soil by

dropping mechanical "pods" capable of communicating with a central

"stem," which would send data back to Earth.

The idea that plants are more than hanging decor at the

dentist's office is not new.

Charles Darwin published

The Power of Movement in Plants

- on phototropism and vine behavior - in 1880, but the concept of

plant intelligence has been slow to creep into the general

consciousness.

At the root of the problem:

assuming that plants

have, or should have, human-like feelings in order to be

considered intelligent life forms, Mancuso says.

Professor Mancuso

blends in with the greenery.

He touches a formerly

neglected office plant.

Photo: Nicole Martinelli

After the folksy 1970s

hit book and stop-motion film

The Secret Life of Plants, which

maintained, sans serious research, that greenery had feelings and

emotions, the scientific community has avoided talking about smarty

plants.

So while there has been a bumper crop of studies demonstrating that

green matter can be nearly as sophisticated as gray matter --

especially when it comes to

signaling and

response systems, few talk

about intelligence.

To christen the lab in 2004, Mancuso decided to use the

controversial term "plant

neurobiology" to reinforce the idea that plants have

biochemistry, cell biology and electrophysiology similar to the

human nervous system. But although LINV is part of the University of

Florence - where Mancuso teaches horticulture - funds for this

fertile field of research weren't forthcoming.

Studies at LINV were eventually given lymph - 1 million Euro so far,

with about 500,000 Euro to come - from the

Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze,

a bank foundation that mainly supports cultural events and art

restorations.

What convinced them to provide seed money?

"Looking beyond the

name at the research," says Paolo Blasi, a physics professor at

the university who's on LINV's board of directors.

"It sounds almost

like a pseudoscientific field, but now even skeptics are

convinced because of the validity of the work."

In addition to studies

on

the effects of music on vineyards,

the center's researchers have also

published papers on gravity

sensing, plant synapses and long-distance signal transmission in

trees.

One important offshoot

of the research activity is an

international symposium on

plant neurobiology. Next year's meeting will be held in Japan.

Leopold Summerer, advanced-concepts team coordinator at the

European Space Agency, remembers that the term "plant

intelligence" raised a few eyebrows when collaboration with the lab

was proposed - even on a multidisciplinary think-tank team that's

used to pondering ideas out of left field.

Nonetheless, Summerer

says plant research may provide important ideas.

"Biometrics can

provide some of the most inspiring resources for us," he says.

"Solutions found by nature that might not seem related to real

engineering problems at first sight actually are related and

give technical solutions."

Radical as the LINV

sounds, if it weren't for a lone sugarcane stalk perched on a

cabinet, the lab looks like any other.

While white-coated researcher Luciana Renna patiently tests

for DNA markers, molecular biologist Giovanni Stefano

analyzes data on two computer monitors around the corner.

During a visit to the lab's two greenhouses - where research is

being conducted on the effects of light on olive trees and reactions

in

Venus flytraps and the

Mimosa pudica - Mancuso points

out a few neglected office plants sent there for a little TLC.

Mancuso, however, is no plant-whisperer.

Under-tended plants are

a long way from understanding sweet nothings spoken softly to them,

he explains.

"Plants communicate

via chemical substances," Mancuso says.

"They have a

specific and fairly extensive vocabulary to convey alarms,

health and a host of other things. We just have sound waves

broken down into various languages, I don't see how we could

bridge the gap."

|