|

by Bob Whitby

March 30, 2016

from

PHYS Website

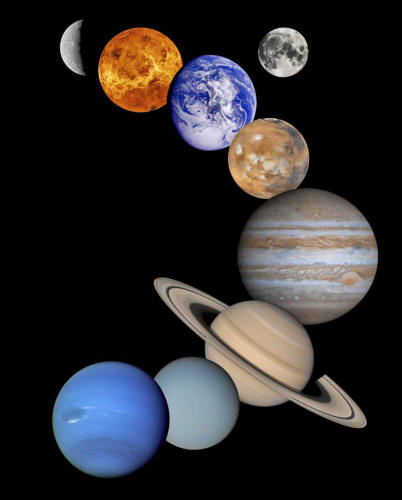

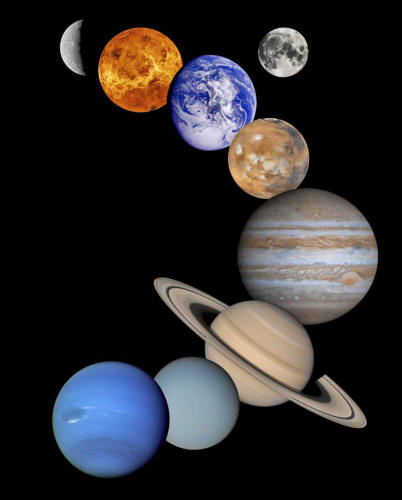

Solar system.

Credit: NASA

Periodic mass extinctions on Earth, as indicated in the global

fossil record, could be linked to a suspected ninth planet,

according to research published by a faculty member of the

University of Arkansas Department of Mathematical Sciences.

Daniel Whitmire, a retired professor of astrophysics now working as

a math instructor, published findings in the January issue of

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society that the as yet

undiscovered "Planet X" triggers comet showers linked to mass

extinctions on Earth at intervals of approximately 27 million years.

Though scientists have been looking for Planet X for 100 years, the

possibility that it's real got a big boost recently when researchers

from Caltech inferred its existence based on orbital anomalies seen

in objects in the Kuiper Belt, a disc-shaped region of comets and

other larger bodies beyond Neptune.

If the Caltech researchers are

correct, Planet X is about 10 times the mass of Earth and could

currently be up to 1,000 times more distant from the sun

Whitmire and his colleague, John Matese, first published research on

the connection between Planet X and mass extinctions (Periodic

Comet Showers and Planet X) in the journal

Nature in 1985 while working as astrophysicists at the University of

Louisiana at Lafayette:

Source

Their work was featured in a 1985 Time

magazine cover story titled, "Did Comets Kill the Dinosaurs? A Bold

New Theory About Mass Extinctions."

At the time there were three explanations proposed to explain the

regular comet showers: Planet X, the existence of a sister star to

the sun, and vertical oscillations of the sun as it orbits the

galaxy. The last two ideas have subsequently been ruled out as

inconsistent with the paleontological record.

Only Planet X remained

as a viable theory, and it is now gaining renewed attention.

Whitemire and Matese's theory is that as Planet X orbits the sun,

its tilted orbit slowly rotates and Planet X passes through the

Kuiper belt of comets every 27 million years, knocking comets into

the inner solar system.

The dislodged comets not only smash into the

Earth, they also disintegrate in the inner solar system as they get

nearer to the sun, reducing the amount of sunlight that reaches the

Earth.

In 1985, a look at the paleontological record supported the idea of

regular comet showers dating back 250 million years. Newer research

shows evidence of such events dating as far back as 500 million

years.

Whitmire and Matese published their own estimate on the size and

orbit of Planet X in their original study.

They believed it would be

between one and five times the mass of Earth, and about 100 times

more distant from the sun, much smaller numbers than Caltech's

estimates.

Matese has since retired and no longer publishes. Whitmire retired

from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette in 2012 and began

teaching at the University of Arkansas in 2013.

Whitmire says what's really exciting is the possibility that a

distant planet may have had a significant influence on the evolution

of life on Earth.

"I've been part of this story for 30 years," he said. "If there is

ever a final answer I'd love to write a book about it."

|