|

by Peter Jamieson November 14, 2011

from

IrishPublic Website

The US government interpretation of the events of 9/11 - a narrative accepted and propagated by the mainstream media - was, in principle, nothing new. It was foreshadowed by more than two thousand years of similar reinventions of what had happened in the past.

The principles of mass psychology, of propaganda, and of perception management - of speaking lies with a straight face - have been used by those in power for many, many years.

The object has always been the same: to drive those who are not of the elite in the direction desired by the elite.

One of the earliest such exercises in psychological coercion through the manipulation of ideas - presented in a series of texts as though it were history - is one which still affects us today.

This is found in the Bible...

The subtle mixture of truth, half-truths and outright lies in the Bible retains the power to fox even the keenest minds of today - even after centuries of lived experience within its moral and devotional atmosphere by Christians and Jews, of careful reflection on its theological ramifications by Church and rabbinical authorities, and dissection by literary critics.

There are clearly no easy answers to be

had on what the Bible is all about.

This isn't to say, of course, that the Bible has caused such abuses: that would be simplistic.

The actual origins of evil lie

elsewhere. But even so, in the presentation of crimes as though they

were acts of wisdom and mercy, the Bible has proven very useful to

State propagandists. Small wonder that the Church became an active

arm of State control, and survived as such for many hundreds of

years.

Another part of the problem lies in our own situation.

Our Western culture is steeped in an even richer set of religious assumptions about the Bible: about its veracity, its literal truth, the semi-idolatrous worship of it as the Word of God.

Is it possible to rise out of these

mazes within mazes, and get a bird's eye view of the problem rather

than a worm's eye view?

Up till then the great tool for unlocking the secrets of the Old Testament had been held to be source criticism, based on Julius Wellhausen's 19th-century distillation of his documentary hypothesis.

This involved the separation of Old Testament historical material, especially the material which ends with the death of Moses, into different sources; these were dated to different periods, and given a designation such as J, E, D, or P.

But from the 1970's the realization began to grow that the great hope of source criticism had led pretty much nowhere, and was in any case methodologically unsound.

With this loss of faith in Biblical dissection there occurred a simultaneous loss of faith in the historical veracity of huge chunks of the Old Testament:

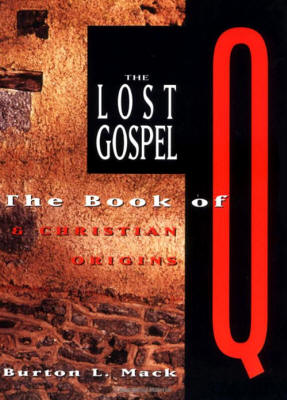

As for the New Testament, a rearguard action was fought by the Jesus Seminar in the US to maintain faith in an historical Jesus - or at least to maintain faith that a connection could be made between us and the historical Jesus through the medium of Q, a hypothetical document extracted from the synoptic Gospels.

Seen as hopelessly revolutionary by US and UK Evangelicals, and hopelessly conservative by European New Testament scholars, the Jesus Seminar's project may have fallen between two stools - though it nevertheless appears replete with many useful observations .

For example, a connection between some of the sayings of Jesus, and the modes of thought and presentation of the Hellenistic Cynic school of philosophy, seems well-founded.

On the other hand, it seems unreasonable

to insist that any historical Jesus who might have existed wasn't

interested in apocalyptic (i.e. insight into the hidden workings of

heaven).

Studies of the Bible-as-propaganda are thin on the ground, and when Biblical scholars in their writings do intimate that the Bible is pulling the wool over the eyes of its readers, they tend to do so between the lines, or in a half-joking, ironic manner. Part of the problem lies in the fact that there are so many people who will take offense.

These are people with a vested interest in something:

Why didn't biblical writers use plain speech?

Even a cursory reading of the Bible proves them to be at best simplistic, at worst examples of a wishful thinking which has no real interest in what the Bible actually says. Naturally, there's an enormous difference between eisegesis (reading one's own ideas into the Bible) and exegesis (exploring what a Biblical author is actually saying), but in practice pure exegesis has always proven difficult, not least because the Bible uses a great deal of metaphorical language.

In other words,

Those parables have to be taken for what they are.

But here there is a problem straight away: we don't really know why parables were used in the first place, and, furthermore, their interpretation is anything but straightforward.

We're presented with texts written in code, and no clear idea of why such a code has been used in the first place.

Why didn't Biblical writers use plain speech?

Whenever thinking is directed by an elite we should expect to see evidence of propaganda at work. In 1956, a book appeared by Robert Jay Lifton: Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism.

Immediately prior to the writing of this book, Lifton had

been a psychiatrist serving with the US Air Force in Japan and

Korea, and the book explored eight ways in which the citizens of

China had been 'brainwashed' (a buzzword of the time) by its

political elite. (A more polite term is 'coercive persuasion',

coined by the organizational behaviorist Edgar Schein.)

But first some general points on thought reform itself: essentially, we're dealing here with a soft approach to mind control. But it's mind control nonetheless, and one of the end results of mind control is a reduced ability to think clearly.

In a social situation characterized by thought reform, mind control, coercive persuasion - whatever we want to call it - a human being can slip by degrees into something like half-wittedness.

The reason for this has to do with the surrounding coercive culture, which itself is half-witted.

And the political culture is half-witted because it deliberately treats certain lines of enquiry as off-limits; these unnatural limits to free enquiry in turn create not just half-wittedness, but also a kind of nervous tension in the individual.

The ratcheting up of this tension can then put his or her inner equilibrium (what we might call their 'general sanity') at some hazard - and particularly so, if that individual has an attraction to truth.

At that point, the

individual has a choice to make: to stay with the craziness of their

culture, or to strike out in a saner direction. The implications of

this rather stark choice are important for each of us, of course,

but also perhaps clarify some lines of development in the Bible.

The narrative of the Book of Ezra is presented as though it were history: straight facts about what happened in the past. However, if accepted as such by the reader, this is a major misconception - because it is a devaluation of how the narrative works: it presumes that the narrative is a whole lot less than it actually is.

In other words, by suggesting that there is nothing in

the Book of Ezra other than facts about the past, we are in danger

of allowing the text to work on us in subtle, unforeseen ways.

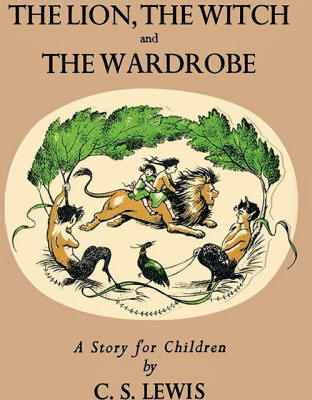

The interesting thing here is that Lewis is defending Biblical texts (especially New Testament texts) as historical, as against legends and romances which are of course fictional.

In general, his remarks are well-made and salutary, but somehow miss the main point.

A "wide and deep and genial experience of literature in general" reveals that what we are dealing with in Biblical texts is legendary and romantic - but written in a particular way for particular ends. In other words, it's propaganda, written as fiction, but presented as straight history - which makes it especially confusing for the reader.

But this confusion is

precisely the point, because the insertion of lies into the reader's

subconscious is never a straightforward procedure.

C.S. Lewis sought to convey his understanding of spiritual truths through fantasy fiction

Take The Chronicles of Narnia, for example.

The Revd Dr Michael Ward has subjected these books to some fairly thorough literary criticism. He showed, in his well-received book Planet Narnia, that the Narnia cycle is not so much a warmed-over Christian apologetic, but something much more cosmic.

Ward makes the case that Lewis, steeped as he was in classical, medieval and Renaissance literature, linked each of the seven Narnia stories to one of the seven traditional planets - and this in a specifically astrological manner. Lewis saw the planets as "spiritual symbols of permanent value" which were "especially worthwhile in our own generation", i.e. in a generation which had lost practically all sense of mystery in both religion and life.

The plot-lines and ornamental details of the books were

allowed to grow, like a climbing rose against a trellis, in

conformity to each of these seven spiritual symbols in turn, so that

a governing planetary personality infuses each book - for instance,

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe conforms to the influence of

Jupiter, Prince Caspian to that of Mars, and so on.

Plus, the notion of seven heavens was important for them too. Naturally, Lewis never intended to reveal what he was doing in these books: to have done so would quite possibly have spoiled the whole effect. Lewis' term for this was the 'kappa element in romance' - 'kappa' being the first letter of the Greek word kruptos, meaning 'hidden' or 'secret'.

This was communication of knowledge by

acquaintance, through exposure to an atmosphere or quality,

everywhere present in the story but nowhere explicit.

Now, Biblical critics have generally taken a somewhat cerebral approach to understanding the Bible - but this is to miss out on the essential lines of force there, which are communicated in rather a different way. Lewis quite rightly treats the Biblical critics of his generation with some disdain, as ivory-tower scholars insulated from the broader approach of literature as literature. When they used the term 'legend' they seemed to have had little grasp of what that term really signified. If they had, they might have found some startling new lines of enquiry stretching out before them.

But surely Lewis was wrong too: if he had seen that the term had been misapplied by Biblical critics, he too might have found something much more significant than mere 'history' in the pages of the Bible.

Perhaps he turned to the writing of fiction in order to explore

these lines of enquiry in an imaginative way, to augment his connaître-knowledge by his own creative mythologizing.

This isn't to denigrate faith in itself, but rather faith misapplied, faith placed in things that are unworthy of it. Faith is an important issue here, because it's in the nature of human beings to apply faith somewhere - even if, in a rationalistic, materialist mindset, the value of faith is denied more or less completely.

Perhaps especially so, if that mindset itself is a lie:

It's one of the truisms of our age that science has taken the place of religion as an ultimate authority: something in which we place our full trust, our full faith.

The word 'science' implies demonstrable knowledge. But simply placing one's faith in science without the necessary checks on its findings, and without being aware that the practice of science is commonly politicized, and scientific data commonly marginalized and ignored in the formulation of 'scientific' conclusions, is surely a misuse of that faith.

Without such checks, placing faith in science becomes a religious matter: a matter of accepting dogma.

There is an inherent vulnerability here, where faith, or trust, is misused, and our outlook - on ourselves and our world - is restricted to narrow, politically-directed norms. This narrow way of thinking is not really scientific in the full sense of the word, but it is symptomatic of literalist religious thinking.

It's dumbed-down

thinking, it induces a dreary half-wittedness in one's own mind and

in social intercourse, and it's thus important in programs of social

control.

What's important in literature is not necessarily the explicit story, but what lies within: the subtext, the implicit truths or lies which bypass conscious controls.

When

viewed in this way, the matter of whether a Biblical text (for

example) is fiction or non-fiction is somewhat immaterial: what

really matters is whether the subtext is true or false, because

that's what will be embedded in the deep psyche unless we find a way

of controlling for it.

Without context it's impossible to fully understand what's happening in a text: the focus becomes too narrow, and the text can then act upon the psyche without responsible controls set by the reader.

Essentially the subtext of a text can work its magic on us (malign or benign), until knowledge of both the subtext and the context of the text reveals that magic at work. Any propagandistic intention can then, with enough scrutiny, be recognized for what it is, and thus reduced or even nullified. This requires both narrow focus and a wide field of view, which is why Biblical (and other literary) analysis is such an exacting scientific field.

But it is

necessary: proper mental and spiritual hygiene is dependent on it,

since otherwise lies become accepted as truth, and then we all

remain idiots!

The Lost Gospel by Burton L. Mack.

Its norms, shibboleths, presuppositions and outlook have, to a large extent, defined Western culture because for a very long time it was read as the very word of God. The fact that you may regard such an idea as crazy is neither here nor there - because it will still control you. Doubly so, in fact, because Biblical analysis may then be sidelined as of little importance, allowing the Bible's propaganda to control the non-reader without check.

Without Biblical analysis, the walls of

the labyrinth that we're in can no longer be seen - they've turned

in effect to glass - which makes the process of negotiating the

labyrinth even harder.

But this is to underestimate the extent to which nearly all Westerners are trapped within a Biblical outlook. At least readers of the Bible have some chance of escape; they are, after all, familiarizing themselves with these texts - however much they may misread them by following Church-endorsed understandings of those texts.

The Biblical scholar Burton Mack, in his book The Lost Gospel, points out something of how a Biblical outlook informs everything in Western culture:

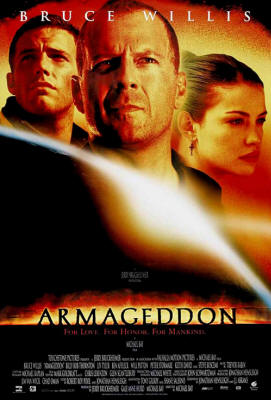

Mack has perhaps coded his points rather abstrusely here.

But on

reflection we might notice how virtually all Hollywood movies

conform to this outlook; and, indeed, how party politics,

advertising, revolutionary activism, TV dramas, national myths, the

prosecution of wars, the writing of history, and the drama of

scientific discovery are also commonly presented in this way.

Trailers for movies like these may well begin with something like:

This format for trailers is common enough for it to be mocked endlessly, but it's still used extensively because it actually does a good job of encapsulating the point of the movie.

The 'one man' is our savior,

and the drama will typically be one of 'destructive violence'

followed by 'creative transformation', as Mack suggests.

This is the twelve-year-old Jesus in the Temple arguing with the teachers there,

Bruce then destroys the incoming asteroid, saving us all from the sting of death in a self-sacrificing ball of flame, and the entire population of the Earth then rejoice at their salvation.

His team (i.e. the Apostles) are all treated as heroes - even though they'd been complete misfits before, or even out-and-out rogues. We don't have to do anything - we just gawp at the pictures on the screen while Bruce Willis does the actual work: that's the vicarious part of the "vicarious crucifixion".

The whole thing is a Gospel story from

start to finish.

But then, we probably knew it

was going to be a Biblical film because it has a Biblical title.

Nevertheless, this sort of thing is actually pretty widespread in

movie-land. Many of the tropes used in present-day dramatic

presentations, on the television and in movies, come originally from

the Bible; and though they have metamorphosed to some extent, they

remain essentially the same.

From this point forward, no drama is going to be satisfying to the audience unless it fits into that paradigm.

That expectation might even play itself out in our minds

as a desire for consistency in how we wish or expect things in the

world to play out - for what we consider the proper form for the

theatre of the thing to work itself out to our satisfaction.

The Bible, then, seems to have provided the format, and nothing very much has changed since. As a result of all this mind-programming, we find it difficult to accept things which don't fit into this format as having either relevance or applicability to our lives.

The Bible, our Biblically-based culture, and the mind-programming which is dependent on these two things, have set up boundaries in the mind - a kind of magic circle or prison, which we have unwittingly become willing parties to.

And, being active partners in the process, it's

self-reinforcing.

But there are others, though, too: for example, party politics. Here 'one man' (one of a number of candidates) plays our savior, and all attention is focused on him, rather than anything else, e.g. party policies, or the political system as a whole. It all comes down to whether this one man has the dramaturgical abilities to act as an unflappable savior-figure, as a modern-day version of the Biblical idea of a king.

The fakery is well-recognized, but we still lack the

ability to side-step the problem; the propaganda is too deeply

ingrained into us.

Who knew a toothpaste or five-blade razor

could change your entire wardrobe, and even clean all the windows of

your home?

Heads of governments are styled as 'saviours'

Scientific discovery isn't accomplished by teams of scientists working co-operatively. No: it seems to be 'one man' playing the role of a noble socially-sidelined savior - or at least an heroic prophet, a lone voice in the desert.

For instance, we have,

...and so on.

But it's all lies.

It's a misrepresentation of the heavenly mysteries - which are likely to be a whole lot better, and a whole lot more marvelous, than the way they're presented in the majority of Biblical texts, and in our modern-day dramatic presentations which echo this Biblical outlook.

The overall effect is that our lives are pre-scripted. And even if we recognize this, and try to act our way out of it, we'll still be reacting in scripted ways.

The Shakespearian comment on this is,

We tend, then, to see things through Bible-colored spectacles.

Everything is a drama, in comparison to which our own lives are fairly banal. The perceived banality of our lives means that they need to be lifted continually by further dramas (e.g. television or movies), which are experienced vicariously, at a distance. Further exposure to these Biblically-inspired dramas makes our lives correspondingly more banal (unless, perhaps - and it's a big perhaps - we're clued in to what is happening).

No attention is given to the day-to-day glories of one's own life, so by extension the lives of other individuals are also just so much rubbish - and if they're snuffed out it in war or disaster it hardly matters. Empathy is thus damaged at the outset.

And one's own responsibilities are also

ignored, because our own lives - the reality of them, that is -

really hardly matter to us.

Destruction and creative transformation are, after all - if it's fair to say so - alchemical ideas to do with the development of a soul; and the activation of the level of reality which stands behind these ideas demands sincerity.

However, in a culture like ours, ruled and undergirded by the Bible, Biblical propaganda suffuses more or less everyone's thinking.

Lies prevail,

and thus the path to sincerity is dangerously undercut before anyone

even sets foot on it.

But wait, there's more! With the Bible we've got a whole blueprint for disaster. Let's take the modern State of Israel. In his book Blood and Religion, the journalist and political analyst Jonathan Cook explores the meaning of the building of the separation barrier, or wall, around the West Bank and Gaza.

The declared purpose of this barrier, to prevent the entry of suicide bombers into Israel, is clearly pabulum for a Western public, largely uninformed and uninterested in the facts on the ground.

It's simply another instance of a lie to be taken as the

truth, which is something we might expect to encounter in any

control system.

We know it's not the truth, because the State of Israel gives a more nuanced reason for the wall's existence to its own Jewish citizens.

Cook explains:

The State of Israel is often assumed to be a 'Western-style democracy'.

But this misses the point of what Israel is, and was set up to be: not so much a 'state of all its citizens' (including Muslims, Christians and Druze), but a specifically Jewish state. As such, it's an ethnocracy.

Cook quotes Oren Yiftachel, a political geographer at Ben-Gurion University in the Negev, who explores the meaning of this term.

Ethnocracies, he notes,

To outside observers, and certainly to most Israeli Jews, it might seem that Yiftachel is rather overstating his point, but again, if that's the case then it's because the context isn't being taken into account.

Cook lists Yiftachel's supporting data:

All these disqualify Israel from being a democracy.

Part of the Israeli 'separation barrier' that imprisons millions of Palestinians

Cook describes how the wall appears to those on the inside, and those on the outside of it:

Cook defines two other walls in Israel beside this concrete and steel one: a glass wall and an iron wall.

The glass wall is the invisible barrier separating Jews from Israeli Arabs, who comprise just over twenty per cent of Israel's citizenry; it's a metaphor for the rigid segregation in Israel between the two groups, despite the fact that the members of each group are equally enfranchised citizens of the same state.

Israeli

Arabs routinely suffer discrimination in terms of personal status,

geography, work, leisure activities and opportunities, but despite

this widespread inequality, many Jews in Israel are barely even

aware that Israeli Arabs exist, let alone that they are

discriminated against.

The term was coined in 1923 by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, whose Revisionist Zionist movement provided the intellectual inheritance of the ruling Likud party in Israel today.

In his essays The Iron Wall (We and the Arabs) and The Ethics of the Iron Wall, Jabotinsky rejected any idea of compromise as unrealistic.

Gentlemanly practice, he said, was hopelessly naïve. No native population would stomach the intrusion of another nation into their territory. So the gloves have to be off. Unremitting force is viewed as the only answer to Arab objections to Zionist control of the territory.

Which for him is fair enough - after all, the Jews are dealing, he says in The Iron Wall, with an inferior people:

In The Ethics of the Iron Wall Jabotinsky cites the Talmud to defend this 'might is right' approach, exemplified today by Israel's vast military which routinely goads and represses Palestinians:

Ze'ev Jabotinsky

After all, the Palestinians already owned the land. It's not as though the two parties came across the same piece of territory at the same time.

What we have here, surely, is a dizzyingly over-complicated example of the logical fallacy known as 'argument to moderation', which asserts that a compromise between two positions must be correct, e.g. Amanda has just baked a pie; random stranger Barney knocks on the door and claims the pie as his own - ergo, half the pie should be given to Barney.

Though in this case, Jabotinsky implies, giving up half the pie would set Barney at risk of only getting a quarter. Best to claim the whole thing, and then take the whole thing, just to be sure.

But surely such a claim is undermined by the fact that Barney is actually a random stranger? So how could the Zionists make any claim on the land?

But of course, if we think that, we have reckoned

without the Bible.

Not that protection is necessarily

the ultimate reason for the walls, but it is nevertheless their

justification. Walls, though, can have a dual purpose. Whatever the

justification given by those who erect them, they are often

constructed, not just to keep the barbarians out, but also to keep

the prisoners in.

Let's go back to the situation in scientific research today. This might seem remote from the plight of Arabs in Palestine, but arguably, nevertheless, similar principles apply.

Mainstream science maintains its own glass wall:

It also has its own version of the concrete wall:

And in extreme cases there's even perhaps an iron wall: the circumstances surrounding the death of Dr David Kelly are still open to question, as are the mysterious deaths of many other scientists - not to mention more than 310 scientists murdered by the Mossad in Iraq after the invasion in 2003. The corruption of science in our own society is an example of the imposition of barriers to the detriment of all.

Small wonder when such obstacles to free enquiry are imposed

all over the world, that a physical barrier is tolerated in

Palestine as pretty normal, and nothing to make a fuss about.

Perhaps an answer lies in the broader context. Is it possible that this, as well as the corruption of science, the defense of economic inequality, and the degradation of spirituality - all under the guise of everything being normal - are political matters which themselves stem to some extent from one and the same charter: a charter which indicates how things should be in a 'normal', tidy society?

This brings us back again to how a text is

read: is it exegesis (the reading of the whole of the text, complete

with subtext and context), or is it eisegesis (the reading into the

text of a lie considered as truth by the reader)?

The first Greek novel that we know about was written round about 100 BC. Astonishingly, this doesn't center on characters in Athens or Rhodes or elsewhere in the classical world - it's about characters that we meet in the Old Testament. The very fact of the novel's existence points to a taste for fiction among the Greek-speaking Jews of Egypt.

It also gives us a hint that

the Old Testament history from which the novel is derived might

itself be somewhat fictional.

The concept of slavery is important here, because it's one of the main lines of force running through the Old Testament, whether threatened, implied or actual. Joseph and Asenath deals with the conversion of Asenath to Judaism, and portrays Judaism as a Mystery religion, like the religions built up around the figures Osiris and Dionysus.

There is a melding here of Jewish,

Egyptian and Hellenistic ideas about the divine, but the Jews seem

especially keen on casting these Mystery myths in the form of

history.

However, simply because this is implied in the text does not make it a fact - and it shows scant respect to the text to take what was quite possibly meant as fiction at face value as though it were fact. Biblical critics of the nineteenth century (and earlier) realized there had been a misreading of the texts as soon as they rejected Mosaic authorship for these books.

Both they, and

the Church at large, have been struggling with the

implications of this ever since - because it implies a traditional

misreading of the whole of Holy Scripture.

(Perhaps these are not the very best terms to use. Propaganda implies something rather obvious and in-your-face, whereas Biblical propaganda is a whole lot more subtle - even devilishly so. Allegory implies a one-to-one correspondence between one thing and another, but again in the Biblical narrative the correspondences are really not so rigid, and are instead rather dream-like, encouraging and non-coercive. But they are the best terms I could think of.)

It is not easy to separate these two approaches in the composition of Biblical texts.

Subversion of the meaning of an original text by propagandists, can then be reversed by counter-subversion by allegorists, which in turn is countered by counter-counter-subversion of the same text by a new generation of propagandists.

You get the picture: it's a terrible muddle. But certain lines of force within the Old Testament as a whole reveal something of what's going on.

(Similar things have happened in the

formation of the New Testament. But the story of the New Testament's

formation, though parallel to the story of the development of the

Old Testament - because similar shadowy groups with contradictory

agendas were involved in the development of each - probably needs to

be kept separate for the time being.)

When you or your children read the bible you are reading the work of 'shadowy groups'

In that sense they are shadowy indeed. And in that

sense we are dealing with something rather like a conspiracy:

unthinkable, of course, but there you go. Our task now is to think

the unthinkable, and just get on with it.

The widespread denial of 'conspiracy' - which is, after all, just a shorthand term for groups working in secret - has, it seems, hampered our understanding of historical processes for a long time. This is partly because we are not willing to see conspiracy at work in the ancient world; instead there is a common fantasy that ancient people were idiots who didn't have the wit to write between the lines.

It was only in

totalitarian Communist and Nazi regimes, so it is said, where all

the elements of mass media were used as tools in support of the

State and its ideology, that propaganda became commonplace - and

even then was only accepted by blockheads. The moderns of the

peace-loving Free World are apparently so much more advanced than

that.

It's indicative of an academic culture invested in a lie. Investment in this particular lie - that there is not, never has been, and never could be conspiracies - gives everyone peace of mind, and confidence in the system (religious, political and scientific). There's a real danger to society here, as well as to spiritual development - we only see part of the picture if we deny certain possibilities right from the outset.

Denial of possibilities means that the situation has been

pre-judged; in other words there is prejudice at work here. Isn't

this contrary to the true spirit of scientific exploration?

The first is propaganda, which we might fairly regard as malign; after all, it seeks a restriction in individuals and populations to secure a political aim.

Naturally, this must be done in secrecy: there can be no public admission that the truth of things is being bent, managed or limited (in the sense that only part of the picture of things is being presented as though it were the whole) - otherwise the effect, of course, is lost completely.

The motive is straightforward: people are lied to in this way, because those creating propaganda believe they are somehow or other in a state of war against their fellow-citizens.

They are

manufacturing consent (in Herman and Chomsky's phrase), and

eliminating dissent.

Examples range from,

Really, they're pretty much ubiquitous.

With propaganda like this so widespread, there is also the chance that propaganda was at work in the creation of more polished, ambitious literature too, particularly when this focused on the creation of a national myth.

Since much of the Old Testament does indeed read like national myth, it's perhaps no wonder that some recent Biblical scholars, especially,

...have drawn attention to this possibility.

What is surprising is that academia has taken so long to cotton on to this possibility.

The reason for that lies for the most part with the corruption of Syro-Palestinian archaeology by advocates of Biblical historicity (even inerrancy), the dominance of Old Testament scholarship itself by conservative Christians (Protestant and Catholic), especially in the US, the flat-footed turgidity of much twentieth-century German scholarship - and last, but certainly not least, the Zionist agenda, whose justification for a modern Jewish state in Palestine lies to a very large extent in the Old Testament.

The Zionist investment in Old Testament historicity is therefore intense.

There are political and religious agendas at work in Biblical scholarship and Syro-Palestinian archaeology.

That much seems obvious.

William G. Dever, until his retirement in 2002, Professor of Near Eastern Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Arizona, is a supporter of the essential historicity of the Biblical narratives, and a critic of scholars such as Thompson and Davies.

In his November 3rd 2009 speech to students at South-western Baptist Theological Seminary, Dever concluded:

This at least has the advantage of showing Dever's agenda. He's taking no pains to disguise it.

After all, for him it's a mark of his devotion to truth - a mark of virtue. And this is not to say that he's not trying to be fair-handed in his scholarship. That's not the point. But nonetheless, for someone like Dever, it comes down to defending a tradition. And 'facts', in both archaeology and Biblical criticism, are seldom what they seem.

Making sense of the

'facts' is a matter of interpretation; and interpretation of a text

(for example, an archaeological datum or a verse in the Bible)

involves divining the subtext, and becoming more and more aware of

the larger context.

Glock's story is perhaps illuminating.

He had come to Israel in 1962 as a Lutheran missionary, and had been the director of the W.F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research in Jerusalem.

Dr Glock's credentials as a Bible-believing - but rational and

scientific - Christian were pretty much second-to-none. But this was

just the beginning of a personal odyssey which led to him becoming

an advocate of an archaeology which placed Palestinians at the heart

of the subject.

This constriction of archaeological investigation is surely perverse.

The introduction to Francis Pryor's recent book The Birth of Modern Britain - A Journey into Britain's Archaeological Past, 1550 to the Present, for example, shows how what had formerly been termed 'industrial archaeology', has now become thoroughly mainstream across the world. No defense is needed in academic circles - however much some outside observers regard archaeology as a kind of glorified treasure-hunt.

Instead,

archaeology of the recent past - even of the late twentieth century

- is regarded as a truly valuable contribution to our understanding

of what happened in the past. Not so, it seems, in Israel, where

discussion of the subject, let alone excavation, is freighted with

controversy. Or worse.

In his book Palestine Twilight - The Murder of Dr Glock and the Archaeology of the Holy Land (published in the US under the alternative title Sacred Geography), Edward Fox describes what happened:

A short editorial note at the end of Glock's article in the Journal of Palestine Studies points to the significance of other details about the murder (which Fox also considers highly significant):

And in the end we cannot know who killed Albert Glock, or why. All we can do is examine what evidence we have, and then look for the lines of force in the total context to show the most probable culprit.

What we do know is that Glock was committed to the

Palestinians as a people he lived among. Immersed in life among the

Palestinians, he and his wife Lois were set to retire there, rather

than in the US - which would have amounted to "living in the

bubble", as he called it.

The occupation levels he excavated covered the 400-year period of Ottoman rule which had ended in 1918 - a period very much neglected in favor of those older periods with some connection to the Bible.

The investigation of the material remains from Ottoman Palestine was also politically charged.

After all, the State of Israel had a myth to maintain:

The investigation of the post-medieval history of the Palestinians, and their material culture - the culture which stood as a witness to their essential humanity - was therefore tacitly off-limits.

Simply by digging up the comparatively recent past, Glock was setting himself against the sacred myths of the Israeli State, and the Zionist project which underlay it.

That was a kind of sacrilege, and it seems fair to

suggest that Glock was murdered for it.

In The Language of Poetry (edited by Allen Tate), Philip Wheelwright explains that,

It's a script which a person can believe in, and believe that all is well.

But myths don't have to be true, or even representative of the truth. They are ripe for subversion by propagandists, and the suspicion is that that's what the Old Testament is: propagandistic subversion of myth, masquerading as history.

It's useful to bear in mind here George Orwell's famous maxim from 1984:

Scribes wrote and interpreted religious laws

Thomas Thompson proposes that the writers of the Old Testament were putting together a set of documents to lend support to a political idea. This idea was based on the traditional political model found throughout ancient western Asia:

The city-state was a social model with slaves and citizens at the bottom, a priesthood above that, and then a king at the top.

Above the king was something more nebulous:

There is a slight complication here: as spokesmen and spokeswomen for the deity, we might assume the priesthood to be on the same level, or even above, the king. Here, though, is where it gets interesting.

The priesthood, in those far-off times, were also scribes, i.e. masters of writing. And what we are concerned with here is the composition of literature.

So who

actually is really in charge? The deity? The king? The priesthood?

Or those specific scribes who produced the supporting, perhaps

propagandizing, literature?

Instead we have a network of forces, and all of these figures are manipulators, or the manipulated - or the manipulated imagining that they're the ones who are manipulating. So the simple model is actually anything but. But it is a model, it was a stable or consistent model, and this was largely because it was pretty simple and easy to remember: everyone knew their place.

The origins of civilization, as we know it, stem from this period. The two revolutions in Mesopotamia, round about 3400 BC, were urban (with the establishment of organized, centralized cities) and literate (with the invention of writing).

The two seem to have gone hand in

hand.

It can be made intensely so - as was the case around 2000 BC with the Third Dynasty of Ur, when matters were hyper-regulated by the priesthood; during this period they maintained a particularly firm control over economic affairs. It may have been found, however, that such a level of control was insupportable or counter-productive.

Or that there were easier, propagandistic, ways to control a population - and these may have involved the figure of the king. But did the king control, or was he controlled?

The extent to which any particular king was important is not always easy to estimate: he may have been something of his own man, while at other times simply the mouthpiece or figurehead for a controlling elite, or something in between.

But whatever the actual circumstances, the model was retained in the population's overall psyche.

And it could be argued that it remains there still.

The suspicious death of William II of England lithograph by Alphonse de Neuville, 1895

After all, there were other figures around him who may have actually been more influential, e.g. Ranulf Flambard, his chief minister, or Lanfranc, who tutored William and secured his accession to the throne.

This may seem somewhat beside the point, but William II was, in some ways, considered a weak or troublesome king, unlike his predecessor (and father) William I, or his successor (and brother) Henry I.

But the terms later applied to him, such as 'weak' and 'troublesome', disguise what was happening politically at the time, which, we may make an educated guess, quite possibly amounted to intrigues behind the scenes. There is nothing inherently unlikely about this scenario - though it's a scenario that, to some extent, troubles the historian all the same.

The very fact that it's

troubling is interesting.

What are the dynamics here?

James I of England (who reigned from 1603 to 1625) believed in the concept of the divine right of kings, which was essentially, as he had argued in his treatise The True Law of Free Monarchies, a Biblical doctrine.

But despite this he was in many ways sidelined by others in his court. There's nothing peculiar about this understanding of Jacobean politics: it was well-known at the time, and it's recognized today.

James' personal rule was not exactly what he hoped it would be: an autocracy - government by one individual. Instead, individuals like Robert Cecil, Robert Carr, and George Villiers were in turn key decision-makers, with others behind them.

Robert Carr, for instance, was subsumed into the Howard party (Henry, Thomas and Charles Howard, William Knollys and Thomas Lake). And there were casualties too.

Much of Carr's work was carried out by

Thomas Overbury, and when they quarreled, Overbury was sent to the Tower,

and there poisoned.

But this, it has long been suggested, had been stage-managed to some extent by the nascent Security Service of the day:

But, as we have seen, there were other

movements off-stage too.

Engraving of eight of the thirteen 'Gunpowder plot' conspirators, by Crispijn van de Passe 1605

That such deliberations take place on a daily basis is acknowledged by everybody. The fact that it is then more or less denied in the next breath simply expresses a wish for something cleaner, something we can believe in.

To some extent, it's a learned

response - exposure of the workings of the control system carries

with it the risk of exclusion from its propagandizing arm, which

today is more or less the whole of mainstream news-reporting,

news-analysis and academe. The propagandizing is effected through

exclusion of data, a subconscious recognition that certain areas of

study or interpretation are off-limits.

The political process in places like France, the US, and the UK is ostensibly democratic: a government by the people, or at least by the people's elected representatives (which is assumed to be much the same thing).

Closed-door discussions are acknowledged, but nevertheless omitted from discussion about the government: one part of political decision-making, parliamentary process, is taken as the whole.

This is not to say that closed-door

discussions aren't the focus of serious debate in some circles, but

there is a tendency for the force of such debate to simply run into

the sand - largely, perhaps, because the influence of private and

corporate interest groups, among others, isn't taken into account.

Indeed, James could hardly say anything else.

When he wrote The True Lawe he could see the possibility of becoming king of England on the death of Elizabeth I - or at least, at the turn of the 17th century, this is what Robert Cecil was attempting to organize. (James had recognized the kingmaker in Cecil, whom he referred to as essentially the monarch of England: "king there in effect".)

Both Elizabeth and James were descendants of William, and their divine right to rule England rested on this single fact, that they were supposedly the ones at the head of the line of succession from William.

It was a little difficult to reconcile the 'divine right of kings', and their legitimacy as rulers, with the fact that it was based on a particularly bloody conquest, when, with the slaying of Harold Godwinson, the last of the Anglo-Saxon kings (whom one might have thought was the divinely-appointed king), a new order of things was imposed by Normandy.

But James hung on to this idea,

that William had not acted against God by conquering England, since

conquest itself - the overturning of the older order of things, and

de-throning of a king - could itself be seen as instituted by God.

Portrait of James I of England by Daniel Mytens

This is not to say that subsequent events were directly caused by the way James articulated his thinking in one single treatise. James was simply laying the case for how a king, and those he ruled, should behave. But the idea was clearly in the air: a king could be overthrown "by force and with a mighty arm" with complete legitimacy.

And ironically that legitimacy had even

been underlined by the king himself - whose son Charles I was, of

course, to be executed for treason in 1649.

On his accession in 1603, James had been presented with the Millenary Petition, a series of demands made by Puritan clergy of the Church of England for changes in church practice, e.g. the abolition of wedding rings, confirmation, and the term 'priest' for ministers.

For Puritans, matters like these were considered 'Popish' errors.

Perhaps trivial to us today, they were nevertheless important matters in this period because of the way in which people understood the nature and function of society, as a hierarchical governmental pyramid, surmounted by God and King, and sanctioned, infused and informed by religious practice.

It was commonly understood that, if religion was practiced wrongly, it could undermine everything. As recently as the early 19th century, for instance, it was still illegal to say that Jesus was anything less than the Son of God.

Such an idea would have struck at the root of the State's legitimacy.

It was only with widespread agitation towards a universal franchise, which passed its first milestone in the 1832 Reform Act, that democracy began to be seen as the basic underpinning of the State, as opposed to something more quasi-mystical based on Mesopotamian city-state ideals inherited through the Bible.

This, though, was a cheat, as were the American and French Revolutions which anticipated the 1832 reform in England.

It serves merely to mask the Biblical hierarchic ideal, which itself

masks a semi-secret oligarchy.

Shakespeare, for example, whose later plays fall in the Jacobean period, shows little evidence of such concern. And in fact James' government was remarkably laissez-faire on religious matters compared to earlier and later periods, such as the reign of Mary I, and the post-Civil War Commonwealth.

But if Catholics tried to assume a low profile, there were others - the Puritans - who wanted a religion stripped of anything Catholic.

These reformers wanted a return to sola scriptura ('by Scripture alone'), but their quasi-Gnostic reliance on their own personal walk with God masked an authoritarian literalist streak about a mile wide.

For them the Bible was the only pertinent authority - but

interpreted by Puritans themselves, who then took it upon themselves

to tell others what to believe and how to live.

The environment, as they understood it with swivel-eyed logic, was 'oppressive', i.e. they couldn't get away with trying to enforce their own ideas on others, whose more moderate ideas smacked of godlessness. Puritans had been the main driving-force behind James' decision to produce a new translation of the Bible, the Authorized King James Bible of 1611.

Ironically, the translators' Dedication of this Bible to James refers to them as,

It was, of course, during the reign of James that the Pilgrims (or Pilgrim Fathers) made their way to America in 1620, largely because they felt that England stifled their religious practice.

For that reason they needed a New England in Massachusetts and beyond, for the,

Under the circumstances, and insofar as the Pilgrims had

settled illegally in Massachusetts rather than Virginia, that last

phrase about king and country seems a little mealy-mouthed, but was

perhaps indicative of a diplomatic need to show at least outward

solidarity with the government of England - particularly as they

expected regular supplies to be ferried out to them from the home

country.

Pilgrims on the Speedwell en route to Massachusetts by Robert W. Weir

Which was a little surprising in that the country teemed with game, the harbors swarmed with fish, and the soil was not unfertile. But then the Pilgrims, naïve as they undoubtedly were, were trying to stick to the terms of their agreement with the Merchant Adventurers, a London trading firm, which stipulated that the Pilgrims should give all their time and labour to the Adventurers for a period of seven years, after which the land would be divided equally between the Pilgrims and the Adventurers.

The Adventurers, however, had not stuck to their end of the bargain by sending regular provisions to the settlers - which meant that the contract was actually null and void.

Caught in a web of assumed

obligation - which itself quite probably stemmed from their

adherence to the rather one-sided contractual obligations set out in

the Bible - the Pilgrims would have ended as a colony were it not

for the basic humanity shown by the Wampanoag people.

It would appear they were expecting trouble from some quarter or other - and Standish was the man to create just such trouble.

An alleged 1625 likeness of published in 1885

This trouble was useful in that it served to knit the

colonists more closely together - a tactic the European settlers in

America continue to use even today.

The colonists, in effect, were digging in, and the

palisade served to keep the purity of those inside free from

contamination outside. It was, in other words, a psychological

measure - a way to emphasize a bunker mentality.

In April 1622 (one month after the palisade had been completed) further settlers arrived, and settled in their new colony of Wessagusset, about 25 miles north of Plymouth. When this colony failed through starvation, many of the settlers there elected to go and live with the Massachusetts tribe.

Standish would have none of it, and ordered them to return to Wessagusset.

The day after Standish's arrival, Pecksuot, a Massachusetts man, came up to Standish and said, looking down on him,

This perceived insult was not to be brooked.

On a prearranged signal the Englishmen shut the door of the one-room house, Standish moved forward, seized Pecksuot's own knife, and stabbed him repeatedly with it.

The two other Massachusetts men who

were in the house with Pecksuot were also murdered, as were the

remaining two waiting outside.

A reconstruction of the original Pilgrim village in Plymouth, Massachusetts, including a replica of the palisade surrounding the settlement

The Governor of Plymouth Colony, William Bradford evidently found the matter to his distaste, but only commented,

The general good here perhaps really means

'the general good of the colonists', which was based to some extent

on State terrorism.

At any rate, in their understanding of themselves, many Americans are happy to return to the Pilgrims as a measure of who they are; it's not something that has been quietly forgotten or marginalized.

From the outset the aim of the Pilgrims was isolationary, an isolation exacerbated by both defensive measures (the palisade), and pre-emptive offensive measures (the massacre).

None of this is any less true today for modern America.

And it's a situation we have already examined in Israel, where a

separation barrier and pre-emptive military strikes are emblematic

of how the Jewish State thinks and behaves. It's interesting too

that religion - a religion where the Old Testament is such a

touchstone for behavior - plays such a major part in the national

ideologies of both Israel and the United States.

The holy scriptures were never far away from the scene; throughout, they provided the rationale or excuse for nearly every political move. The seeds of England's Revolution and Civil War, which began in 1640, and culminated in the execution of the king in 1649, were sown in the reign of King James.

And it was in this same period that the colonization of New England from across the Atlantic also began.

Both movements were characterized by Puritanism, a strain of thinking that emphasized self-reliance, devotion to the Bible as the ultimate authority (since the Bible was reckoned the only revelation of God available to hand), the responsibility of fulfilling contracts and obligations (however crazy or one-sided such a contract or obligation might be, or invalid due to the non-fulfillment of their terms of the contract by the other party), a desire to straighten others out (or at least those within one's own community), and an inward-looking, defensive posture that encouraged parochialism.

However adventurous and seemingly

responsible such people may appear to be, it may nevertheless be

fair to say that these tendencies are actually evidence of

narrow-mindedness and egotism.

When the Pilgrims established their colony at Plymouth, they were surprised at the way the first American Indian to make spoken contact with them made his entrance. His name was Samoset.

Here is the event, as described in Mourt's Relation, which was first published in 1622 (spelling modernized):

The Pilgrims treated him well, and seem to have been much impressed by him.

Nevertheless, it's perhaps telling that they should remark on his boldness, as though boldness itself were somehow surprising or inappropriate. This may partly be due to a certain racism, to a belief that a 'savage' was somehow less of a man than themselves.

No doubt this was a view taken by many Europeans at that time, and up to the present day. This had been the attitude which had encouraged Thomas Hunt, one of John Smith's lieutenants at Jamestown, when he had engaged in a spot of slave-taking up the coast.

Again, from Mourt's Relation:

The Pilgrims seem clearly to have been incensed by such a practice.

And it would obviously have been bad for the trade in beaver-skins they were keen to engage in with the Indians. The Wessagusset massacre obviously scotched this trade, and it's interesting that Plymouth's Governor thought not to censure Standish for this, if only on economic rather than humanitarian grounds.

The sale of beaver-skins in London was, after all, a primary way of raising revenue for the colony.

But 'putting the fear of God' into the

natives seems to have been thought a matter of more urgency - either

that, or, as may be more likely, Standish himself was now

effectively the master of the colony rather than the Governor.

The Pilgrims seemed to have no compunction about robbing Indian graves and entering Indian villages, but for Indians to walk into their territory without asking leave as though it were natural and normal perplexed the colonists. (Isn't there something of this attitude in how Israel restricts the free passage of Palestinians into 'its' territory, as though such restrictions were completely normal?)

Plymouth was somehow under the ownership of the

colonists - although there had been no negotiation with the locals

about this. Not that the locals would have recognized such claims,

of course.

But the Governor, William Bradford, ignoring these factors, felt that after four years the merits of communism had been disproved.

Governor William Bradford

He explains:

So - people are naturally wicked, and because of this cannot combine to work for the good of the whole.

The fact that Plymouth increased in prosperity after each family had been given an acre of land to farm on their own, was held to be due to this change, rather than to the fact that the colony no longer sought to keep to the terms of their agreement with London, and had become better adapted to their new surroundings and circumstances.

The corrupt nature of humanity was of course a foundation-stone of Calvinism. It meant that people had to be shepherded if they were to keep to the correct course.

Perhaps there is more than a grain of truth here, but it was

nevertheless used, as we see in the above quotation from Bradford,

strictly to support the idea of private ownership of land.

Among these men were Bradford himself, and Standish. In return for assuming all financial responsibility, the Undertakers were allowed a monopoly over all trade and fishing rights, control of prices and wages, and general oversight of all aspects of the colony's economy.

Within seven years of arriving at Plymouth, communism had been

supplanted by an oligarchy, and the oligarchs had awarded themselves

the best land, the best cattle, and the best meadows for hay.

The colony continued to be ostensibly democratic and held to the principle of equality. But the oligarchy maintained control of the church, which became an instrument of 'correction', with many pettifogging rules.

We hear for instance of how Samuel Gorton was expelled from the colony apparently because his wife's maid had smiled during a church service.

And the colony was stratified into a social pyramid, with the Undertakers at the top, the church members immediately beneath, then a third group (disparagingly referred to as the 'Inhabitants'), who were regarded as potential members of the church, and the servants, apprentices and slaves at the very bottom.

So it was not

quite so egalitarian at Plymouth as we have been led to believe.

It's part of the national myth of the United States, and thus continues to lend justification to what it does.

It is supposed to represent a profound break from Jacobean politics, which was based on the concept of the hierarchic state, with King James at the top, supported by church regulation. Of course there was something of a myth itself at the heart of Jacobean politics.

A lot of things came down to money, and the power derived from money.

It was convenient

to have a king who was always short of cash; after all, as a

figurehead controlled by other interests, if the king had easy

access to money he could not be controlled so easily. Political

parties in the UK and US find themselves in a similar situation,

most likely for this very reason: after all, they too are

figureheads, controlled by other interests.

But what was interesting here was the idea of revolution, the idea of abolition of the old order. Right up until the early 17th century, the idea of replacing the old pyramid of power with a king at the top was pretty much unheard of.

But from the Jacobean period onwards, the idea began to gather steam. The Pilgrims were respectfully declining to follow church practice in England.

This was the reason they had made their journey across the Atlantic. And that's why the Pilgrims are still venerated so highly in the US today.

Although they were deferent to James (at least outwardly), they mark the beginnings of a defiance against Britain. This was a quiet sort of revolution or declaration of independence. And like any revolutionary movement, those outside its walls were treated as less than human.

Hence the way that Standish could get away with serial murder, and hence the way the US behaves today.

In the US everyone is an American, and in a patronizing display of solidarity American Indians are termed 'Native Americans' (even though Indians generally like to refer to themselves as 'Indians', or 'American Indians' to distinguish themselves from people from India), Arab citizens of the US are termed 'Arab Americans', blacks are termed 'African Americans', as though somehow this makes everything alright.

This is a sign of how important it is seen in the US to

belong to the club - and how dangerous it might be to be 'beyond the

pale' (which is a rather appropriate term in this context).

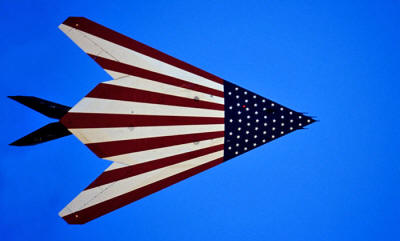

Wrap anything in an American flag and it becomes acceptable

This probably accounts for the extraordinary veneration of the American flag by its citizens. A lack of interest in the flag might mark the citizen out as lacking in revolutionary spirit or sympathy, fellow-travelers of some alternative way of doing things, i.e. they're somehow 'unAmerican' - a word non-US citizens have a hard time getting to grips with.

Everything has to be draped in the flag before it's acceptable - and unacceptable things can be draped in the flag, and voilà, they're totally acceptable.

This doesn't happen anywhere else in the world, where the open display of national flags by private citizens is quite often associated with right-wing looneys.

It also explains how, despite the pioneer spirit, US citizens are generally hesitant about travelling abroad.

Foreigners after all are unAmerican,

because - shockingly - they generally don't give a damn about the

American Revolution. They can be appreciated at a distance, through

the pages of National Geographic, where they're presented as folksy,

quaint, and exotic.

The psychological links between the US and Israel are reasonably clear.

Both are following much the same Old Testament-defined trajectory, although with Israel there's something a little more vicious. Presenting itself primarily as a persecuted people, it gives itself carte blanche to do as it pleases.

As

a rogue state with little interest in the world outside

the Jewish diaspora, Israel has intentionally marginalized itself.

This, of course, is one of the problems with the concept of purity. In trying to be a purer community, to be more committed to the community's ideals, the wall thrown up between that community and the rest of the world can lead to the intensification of peculiar, even perverse, ideas.

The rest of the world might provide saner ways of doing things, or a more balanced context, but the wall prevents those ideas leaking through.

...have all spiraled down into something parochial, off-balance, superstitious and defensive.

Each cherishes its walls, but the isolation imposed by the walls drives them crazy. Each has a skewed kind of purity.

Why do people put up with this?

Well, the drive for this kind of purity is fundamentally religious, and it's based on lies which are a little difficult to spot. A belief in a lie causes a certain congestion in thinking, and the believer becomes a half-wit. Ever wonder why certain people are dimwits? It's useful to look at what politico-religious lies they believe. And the same goes for each of us.

A useful rule of thumb is: It's all

politics, it's all religion, and it's all a pack of lies.

This is why quite a few Americans are happy to contrast 'new' America with 'old' Europe.

By and large it seems to make little sense to Europeans, who have seen a comparable amount of political change themselves since the late 18th century.

And it's not as though the European inhabitants of America don't share exactly the same roots.

The American Revolution is thought to mark a sharp break with the old. It was thus a deliberate act of sacrilege against the old religio-political order, in an attempt to reach a higher level of holiness. In doing this, other countries across the Atlantic (where the majority of immigrants had come from) were deemed to be backward and superstitious.

They were thus cast in

the same mold as Protestants had cast Catholics - and again Jacobean

political thinking has a part to play in this. The political

rejection of Europe had its religious roots in the rejection

of

Rome.

This is even more the case today, when an American king (albeit elected for a 4-year term) is largely free to do as he wishes, at least in foreign policy - and in practice cannot be impeached, whatever crimes he commits.

So things aren't always what they seem:

The American revolution was supposed to be a rejection of the pyramid of power, but the pyramid still exists today

A similar problem occurs when we look at the modern president of the US - is he actually the one in charge, or is he a figurehead for a controlling elite, perhaps comprising people working in an official capacity in the White House, perhaps not, who actually call the shots? Having power, while not being accountable for it, is actually quite helpful for such people.

When things go wrong politically, the figurehead can always be made the scapegoat. For a controlling elite, if a figurehead begins to assume some real power, and to be going in a direction they dislike, they may even contemplate assassination.

The deaths of both John F. Kennedy and

William II - both shot in mysterious circumstances - may make more

sense within this broader context.

Property, though, was an emotional issue for them, because at heart such people are mostly confirmed materialists. It's possible that the majority of the elite are in fact psychopathic, with no functioning conscience. Enjoyment in life for them boils down to power, the misuse of that power, and a delight in lies.

Spirituality, then, has no place in their understanding of

themselves or the world, unless it can be used to deceive others.

But there are New Testament tropes which can also be used, and they have a particularly important part to play in revolution. Mack summed this up in The Lost Gospel, which I quoted earlier.

It's rather a dense passage, but it's critically important, which makes some of it worth repeating here:

This summarizes the arc of revolution quite well.

The Gospel story has been plundered for its dramatic symbols, and then put to use to further social control. And make no mistake about it, revolutions have very often tended to be about social control.

The first revolution of note in modern European history is the English Revolution, which began 15 years after the death of James I.

Events in James' reign had sowed the seeds of it, and in a way the English Civil War (1642 to 1651) was simply a newer version of jostling for control in government - done this time under authority of Parliament and against the king, rather than in the court and with the favor of the king.

To contemporary observers, on whatever side of the fence

you were, it must have seemed that all bearings had been lost - and

indeed The World Turned Upside Down was the title of a popular

ballad of the time.

The Civil

War was of course religious, but then, as well as now, religion lies

at the root of revolutionary politics - for all the reasons Mack

enumerates. In both America and Britain things were being turned

upside-down, which is what the term 'revolution' literally implies.

In both countries the sanctity of kingship (itself an Old Testament

trope) was replaced with other Biblical tropes.

But Holy Scripture remains even now at the heart of everything as a way of corrupting our perception of reality, and thus remains a primary psycho-social tool.

As far as the control system is concerned, nobody needs to be a Christian any more, because everything has now been taken out of our hands: Biblical dramas are imposed upon us from without, whether we like it or not.

Those who cannot recognize any other way of doing things (and they constitute roughly half the human population) go along with a certain measure of enthusiasm, blindly following their leaders, or overthrowing them and then clamoring for a new 'saviour'.

The other half of humanity can then make a choice - which

practically speaking may not seem much of a choice at all, given the

circumstances. That choice comes down to either accepting the lies -

or seeing them for what they are, and so rejecting them.

|