|

Between sunset and sunrise there has been the night. The Bible constantly saw the Creator's awesomeness in the "Host of Heaven" - the myriads of stars and planets, moons and moonlets that twinkle in the Vault of Heaven as night falls.

The "heavens" thus described were the nightly skies; and the glory they bespoke was conveyed to Mankind by astronomer-priests. It was they who made sense of the countless celestial bodies, recognized stars by their groups, distinguished between the immovable stars and the wandering planets, knew the Sun's and Moon's movements, and kept track of Time - the cycle of sacred days and festivals, the calendar.

The sacred days began at dusk on the previous evening - a custom still retained in the Jewish calendar. A text which outlined the duties of the Urigallu priest during the twelve-day New Year festival in Babylon throws light not only on the origin of priestly rituals later on, but also on the close connection between celestial observations and the festival's proceedings.

In the discovered text (generally considered to reflect, as the priest's title URI.GALLU itself, Sumerian origins) the beginning, dealing with the determination of the first day of the New Year (the first of the month Nissan in Babylon) according to the spring equinox, is missing.

The inscription starts with the instructions for the second day:

Then, putting on a garment of pure white linen, he could enter into the presence of the great God (Marduk in Babylon) and recite prescribed prayers in the Holy of Holies of the ziggurat (the Esagil in Babylon).

The recitation, which no one else was to hear, was deemed so secret that after the text lines in which the prayer was inscribed, the priestly scribe inserted the following admonition:

After he finished reciting the secret prayer, the Urigallu priest opened the temple's gate to let in the Eribbiti priests, who proceeded to "perform their rites, in the traditional manner," joined by musicians and singers. The text then details the rest of the duties of the Urigallu priest on that night. "On the third day of the month Nisannu" at a time after sunset too damaged in the inscription to read, the Urigallu priest was again required to perform certain rites and recitations; this he had to do throughout the night, until "three hours after sunrise," when he was to instruct artisans in the making of images of metal and precious stones to be used in ceremonies on the sixth day.

On the fourth day, at "three and one third hours of the night," the rituals repeated themselves but the prayers now expanded to include a separate service for Marduk's spouse, the Goddess Sarpanit. The prayers then paid homage to the other Gods of Heaven and Earth and asked for the granting of long life to the king and prosperity to the people of Babylon. It was thereafter that the advent of the New Year was directly linked to the Time of the Equinox in the constellation of the Ram: the heliacal rising of the Ram Star at dawn.

Pronouncing

the blessing "Iku-star" upon the "Esagil, image of heaven and

earth," the rest of the day was spent in prayers, singing and music

playing. On that day, after sunset,

the Enuma elish, the Epic of

Creation, was recited in its entirety.

The text which we have been following (per F. Thureau-Dangin, Rituels accadiens and E. Ebeling in Altorientalische Texte zum alien Testament) deals, however, only with the duties of the Urigallu priest; and we read that on that night the priest, at "four hours of the night," recited twelve times the prayer "My Lord, is he not my Lord" in honor of Marduk, and invoked the Sun, the Moon, and the twelve constellations of the zodiac.

A prayer to the Goddess followed, in which her epithet, DAM.KLANNA ("Mistress of Earth and Heaven") revealed the ritual's Sumerian origin. The prayer likened her to the planet Venus "which shines brilliantly among the stars," naming seven constellations. After these prayers, which stressed the astronomical-calendrical aspects of the occasion, singers and musicians performed "in the traditional manner" and a breakfast was served to Marduk and Sarpanit "two hours after sunrise."

The Babylonian New Year rituals evolved from the Sumerian AKITI ("On Earth Build Life") festival whose roots can be traced to the state visit by Anu and his spouse Antu to Earth circa 3800 BC., when (as the texts attest) the zodiac was ruled by the Bull of Heaven, the Age of Taurus. We have suggested that it was then that Counted Time, the calendar of Nippur, was granted to Mankind. Inevitably, that entailed celestial observations and thus led to the creation of a class of trained astronomer-priests.

Several texts, some well preserved and some surviving only in fragments, describe the pomp and circumstance of Anu's and Antu's visit to Uruk (the biblical Erech) and the ceremonies which became the rituals of the New Year festival in the ensuing millennia.

The works of F. Thureau-Dangin and E. Ebeling still constitute the foundation on which subsequent studies have been based; the ancient texts were then brilliantly used by teams of German excavators of Uruk to locate, identify, and reconstruct the ancient sacred precinct - its walls and gates, its courtyards and shrines and service buildings, and the three principal temples:

Of the many volumes of the archaeologists' reports (Ausgrabungen der Deuischen Forschungsgemeinschaft in Uruk-Warka), of particular interest to the remarkable correlation of ancient texts and modern excavations are the second (Archaische Texte aus Uruk) and third (Topographie von Uruk) volumes by Adam Falkenstein.

Surprisingly, the texts on the clay tablets (whose scribal colophons identify them as copies of earlier originals) clearly describe two sets of rituals - one taking place in the month Nissan (the month of the spring equinox) and the other in the month Tishrit (the month of the autumnal equinox); the former was to become the Babylonian and Assyrian New Year, and the latter was retained in the Jewish calendar following the biblical commandment to celebrate the New Year "in the seventh month," Tishrei.

While the reason for this diversity still mystifies scholars, Ebeling noted that the Nissan texts appear to have been better preserved than the Tishrei texts which are mostly fragmented, suggesting a clear bias on the part of the later temple scribes; and Falkenstein has noted that the Nissan and Tishrei rituals, seemingly identical, were not really so; the former stressed the various celestial observations, the latter the rituals within the Holy of Holies and its anteroom. Of the various texts, two main ones deal separately with evetime and sunrise rituals.

The former, long and well preserved, is especially legible from the point at which Anu and Antu, the divine visitors from Nibiru, are seated in the courtyard of the sacred precinct at evetime, ready to begin a lavish dinner banquet. As the Sun was setting in the west, astronomer-priests stationed on various stages of the main ziggurat were required to watch for the appearance of the planets and to announce the sighting the moment the celestial bodies appeared, beginning with Nibiru:

As these compositions ('To the one who grows bright, the heavenly planet of the Lord Anu" and "The Creator's image has arisen") were recited from the ziggurat, wine was served to the Gods from a golden libation vessel. Then, in succession, the priests announced the appearance of Jupiter, Venus, Mercury, Saturn, Mars, and the Moon.

The ceremony of washing the hands followed, with water poured from seven golden pitchers honoring the six luminaries of the night plus the Sun of daytime. A large torch of "naphtha fire in which spices were inserted" was lighted; all the priests sang the hymn Kakkab Anu etellu shamame ("The planet of Anu rose in the sky"), and the banquet could begin. Afterward Anu and Antu retired for the night and leading Gods were assigned as watchmen until dawn. Then, "forty minutes after sunrise," Anu and Antu were awakened "bringing to an end their overnight stay."

The morning proceedings began outside the temple, in the courtyard of the Bit Akitu ("House of the New Year Festival" in Akkadian). Enlil and Enki were awaiting Anu at the "golden supporter," standing by or holding several objects; the Akkadian terms, whose precise meaning remains elusive, are best translated as "that which opens up the secrets," "the Sun disks" (plural!) and "the splendid/ shining posts."

Anu then came into the courtyard accompanied by Gods in procession. "He stepped up to the Great Throne in the Akitu courtyard, and sat upon it facing the rising Sun." He was then joined by Enlil, who sat on Anus right, and Enki, who sat on his left; Antu, Nannar/Sin, and Inanna/Ishtar then took places behind the seated Anu. The statement that Anu seated himself "facing the rising Sun" leaves no doubt that the ceremony involved a determination of a moment connected with sunrise on a particular day - the first day of Nissan (the spring Equinox Day) or the first day of Tishrei (the autumnal Equinox Day).

It was only when this sunrise ceremony was completed, that Anu was led by one of the Gods and by the High Priest to the BARAG.GAL - the "Holy of Holies" inside the temple. (BARAG means "inner sanctum, screened-off place" and GAL means "great, foremost." The term evolved to Baragu/Barukhu/Parakhu in Akkadian with the meanings "inner sanctum, Holy of Holies" as well as the screen which hides it. This term appears in the Bible as the Hebrew word Parokhet. which was both the word for the Holy of Holies in the temple and for the screen that separated it from the anteroom.

The traditions and rituals that began in Sumer were thus carried on both physically and linguistically.) Another text from Uruk, instructing the priests regarding daily sacrifices, calls for the sacrifice of "fat clean rams, whose horns and hooves arc whole," to the deities Anu and Antu, "to the planets Jupiter, Venus, Mercury, Saturn and Mars; to the Sun as it rises, and to the Moon on its appearance."

The text then explains what "appearance" means in respect to each one of these seven celestial bodies: it meant the moment when they come to rest in the instrument which is "in the midst of the Bit Mahazzat" ("House of Viewing"). Further instructions suggest that this enclosure was "on the topmost stage of the temple-tower of the God Anu."

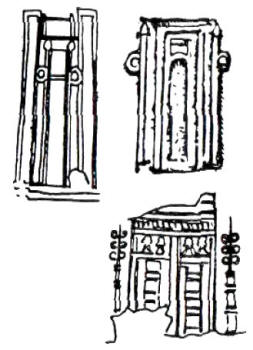

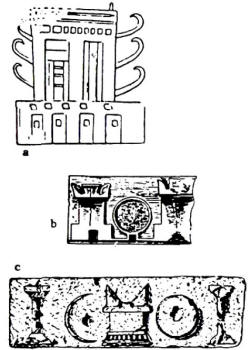

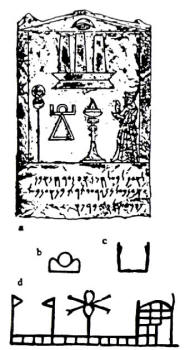

Depictions have been found that show divine beings flanking a temple entrance and holding up poles to which ring-like objects are attached. The celestial nature of the scene is indicated by the inclusion of the symbols of the Sun and the Moon (Fig. 56).

Figure 56

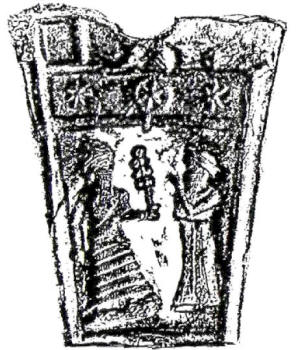

Figure 57

In one instance the ancient artist may have intended to illustrate the scene described in the Uruk ritual text - depicting Enlil and Enki flanking a gateway through which Anu is making a grand entrance. The two Gods are holding posts to which viewing devices (circular instruments with a hole in the center) are attached (which is in accord with the text that spoke of Sun disks in the plural); the Sun and Moon symbols are shown above the gateway (Fig. 57).

Other depictions of poles-with-rings freestanding, not held up, flanking temple entrances (Fig. 58) suggest that they were the forerunners of the uprights that flanked temples throughout the ancient Near East in ensuing millennia, be it the two columns at Solomon's temple or the Egyptian obelisks. Figure 58

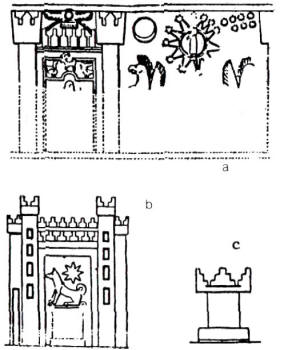

That these originally had an actual and not just symbolic astronomical function could be gathered from an inscription by the Assyrian king Tiglatpileser I (1115-1077 BC.) in which he recorded the restoration of a temple to Anu and Adad that was built 641 years earlier and that had been lying in ruins for the past sixty years.

Describing how he cleared the debris to reach the foundation and followed the original layout in the reconstruction, the Assyrian king said:

According to this account, the two great towers of the temple were not just architectural features, but served an astronomical purpose. Walter Andrae, who led some of the most fruitful excavations in Assyria, expressed the view that the serrated "crowns" that topped towers that flanked temple gateways in Ashur, the Assyrian capital, indeed served such a purpose (Die Jungeren Ishtar-Tempel).

He found confirmation for that conclusion in relevant illustrations on Assyrian cylinder seals, such as in Fig. 59a and 59b, that associate the towers with celestial symbols. Figures 59a, 59b, and 59c

Andrae surmised that some of the depicted altars (usually shown together with a priest performing rites) also served a celestial (i.e., astronomical) purpose. In their serrated superstructures (Fig. 59c) these facilities, high up temple gateways or in the open courtyards of temple precincts, created substitutes for the rising stages of the ziggurats as ziggurats gave way to the more easily built flat-roofed temples.

The Assyrian inscription also serves as a reminder that not only the Sun at dawn, and the accompanying heliacal rising of stars and planets, but also the nightly Host of Heaven were observed by the astronomer-priests. A perfect example of such dual observations concerns the planet Venus, which because of its much shorter orbit time around the Sun than Earth's appears to an observer from Earth half the time as an evening star and half the time as a morning star.

A Sumerian hymn to Inanna/lshtar, whose celestial counterpart was the planet we call Venus, offered adoration to the planet first as an evening star, then as a morning star:

After describing how both people and beasts retire for the night "to their sleeping places" after the appearance of the Evening Star, the hymn continues to offer adoration to Inanna/Venus as the Morning Star:

While such texts throw light on the role of the ziggurats and their rising stages in the observation of the night sky, they also raise the intriguing question: did the astronomer-priests observe the heavens with the naked eye, or did they have instruments for pinpointing the celestial moments of appearances?

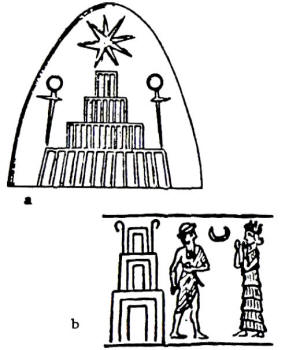

The answer is provided by depictions of ziggurats on whose upper stages poles topped by circular objects are emplaced; their celestial function is indicated by the image of Venus (Fig. 60a) or of the Moon (Fig. 60b). Figures 60a and 60b

The hornlike devices seen in Fig. 60b serve as a link to Egyptian depictions of instruments for astronomical observations associated with temples. There, viewing devices consisting of a circular part emplaced in the center of a pair of horns atop a high pole (Fig. 61a) were depicted as raised in front of the temples to a God called Min.

His festival, celebrated once a year at the time of the summer solstice, involved the erection of a high mast by groups of men pulling cords - a predecessor, perhaps, of the Maypole festival in Europe. Atop the mast are raised the emblems of Min - the temple with the viewing lunar horns (Fig. 61b). Figures 61a, 61b, and 61c

The identity of Min is somewhat of a mystery. The evidence suggests that he was already worshiped in predynastic times, even in the archaic period that preceded pharaonic rule by many centuries. Like the earliest Egyptian Neteru ("Guardians") Gods, he had come to Egypt from somewhere else. G.A. Wainwright ("Some Celestial Associations of Min" in the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. XXI) and others believe that he had come from Asia; another opinion (e.g., Martin Isler in the Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, vol. XXVII) was that Min had arrived in Egypt by sea.

Min was also known

as Amsu or Khem, which according to E.A. Wallis Budge (The Gods of

the Egyptians) represented the Moon and meant "regeneration" - a calendrical connotation.

What is certain is that Min was deemed to be related celestially to the Bull of Heaven, the zodiacal constellation of Taurus, whose age lasted from about 4400 BC. to about 2100 BC. The viewing devices that we have seen in the Mesopotamian depictions and those associated with Min in Egypt thus represent some of the oldest astronomical instruments on Earth. According to the Uruk ritual texts, an instrument called Itz Pashshuri was used for the planetary observations.

Thureau-Dangin translated the term simply as "an apparatus"; but the term literally meant an instrument "that solves, that unlocks secrets." Was this instrument one and the same as the circular objects that topped poles or posts, or was the term a generic one, meaning "astronomical instrument" in general? We cannot be sure because both texts and depictions have been found, from Sumerian times on, that attest to the existence of a variety of such instruments.

The simplest astronomical device was the gnomon (from the Greek "that which knows"), an instrument which tracked the Sun's movements by the shadow cast by an upright pole; the shadow's length (growing smaller as the Sun rose to midday) indicated the hourly time and the direction (where the Sun's rays first appeared and last cast a shadow) could indicate the seasons.

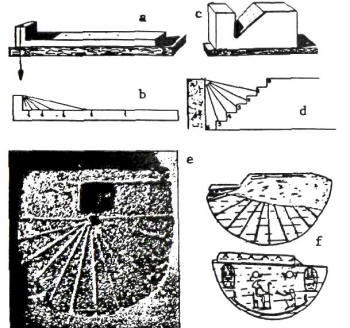

Archaeologists found such devices at Egyptian sites (Fig. 62a) which were pre marked to show time (Fig. 62b). Since at solstice times the shadows grew inconveniently long, the flat devices were improved by inclining the horizontal scale, thereby reducing the shadow's length (Fig. 62c). In time, this led to actual structural shadow clocks which were built as stairways that indicated time as the shadow moved up or down the stairs (Fig. 62d). Figures 62a, 62b, 62c, 62d, 62e and 62f

Shadow clocks also developed into sundials when the upright pole was provided with a semicircular base on which an angular scale was marked. Archaeologists have found such instruments at Egyptian sites (Fig. 62e), but the oldest device so far discovered comes from the Canaanite city of Gezer in Israel; it has the regular angular scale on its face and a scene of the worship of the Egyptian God Thoth on the reverse side (Fig. 62f).

This sundial, made of ivory, bears the cartouche of the Pharaoh Merenptah, who reigned in the thirteenth century BC. Shadow clocks are mentioned in the Bible. The Book of Job refers to portable gnomons, probably of the kind shown in 62a, that were used in the fields to tell time, when it observes that the hired laborer "earnestly desireth the shadow" that indicated it was time to collect his daily wages (Job 7:2).

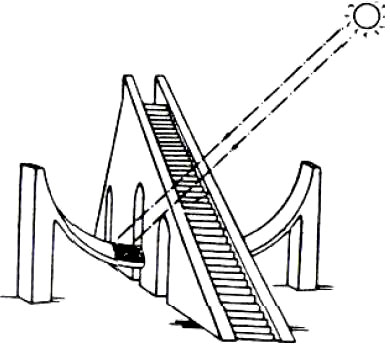

Less clear is the nature of a shadow clock that featured in a miraculous incident reported in II Kings chapter 20 and Isaiah chapter 38. When the prophet Isaiah told the ailing King Hezekiah that he would fully recover within 122 WHEN TIME BEGAN three days, the king was disbelieving. So the prophet predicted a divine omen: instead of moving forward, the shadow of the Temple's sun clock would be "brought ten degrees backward.''

The Hebrew text uses the term Ma'aloth Ahaz, the "stairs" or "degrees" of the King Ahaz. Some scholars interpret the statement as referring to a sundial with an angular scale ("degrees") while others think it was an actual stairway (as in Fig. 62d). Perhaps it was a combination of the two, an early version of the sun clock that still exists in Jaipur, India (Fig. 63).

Figure 63

Be it as it may, scholars by and large agree that the sun clock that served as an omen for the miraculous recovery of the king was in all probability a gift presented to the Judean King Ahaz by the Assyrian king Tiglatpileser II in the eighth century BC. In spite of the Greek name {gnomon) of the device (whose use continued into the Middle Ages), it was not a Greek invention nor, it seems, even an Egyptian one. According to Pliny the Elder, the first-century savant, the science of gnomonics was first described by Anaximander of Miletus who possessed an instrument called "shadow hunter."

But Anaximander himself, in his

work (in Greek) Upon Nature (547 BC.) wrote that he had obtained the

gnomon from Babylon.

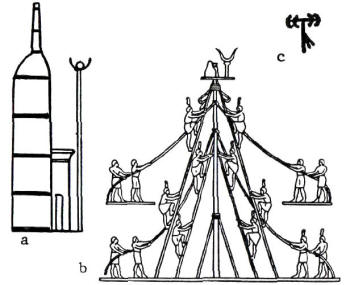

Such altars had four "horns," a Hebrew term (Keren) that also meant "corner" as well as "beam, ray" - terms suggesting a common astronomical origin. Pictorial evidence supporting such a possibility ranges from early depictions of ziggurats in Sumer, where "horns" preceded the circular objects (Fig. 64a) all the way to Greek times. In tablets depicting altars from several centuries after Hezekiah's time, we can see (Fig. 64b) a viewing ring on a short support placed between two altars; in a second illustration (Fig. 64c) we can see an altar flanked by devices for Sun viewing and Moon viewing. Figures 64a, 64b, and 64c

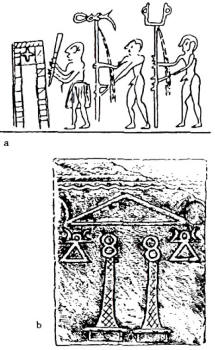

In considering the astronomical instruments of antiquity, we are in fact dealing with knowledge and sophistication that go back millennia to ancient Sumer. One of the most archaic depictions from Sumer that shows a procession of temple attendants holding tools and instruments, pictures one of them holding a pole surmounted by an astronomical instrument: a device that connects two short posts with sighting rings on their tops (Fig. 65a).

The twin rings in such an arrangement are familiar even nowadays in modern binoculars or theodolites for creating and measuring depth and distance. By carrying it, the attendant makes clear that it was a portable device, an instrument that could be emplaced in various viewing positions. Figures 65a and 65b

If the process of celestial observation

progressed from massive ziggurats and great stone circles to lookout

towers and specially designed altars, the instruments with which the

astronomer-priests scanned the heavens at night or tracked the Sun

in daytime must have progressed in tandem.

There they adopted as their main divine symbol the depiction of an astronomical instrument; before it began to appear on stelae and even tombstones, it was shown in association with two double-ringed pillars that flanked the entrance to a temple (Fig. 65b) - as earlier in Mesopotamia. The ring flanked by two opposite facing crescents suggests observations of the Sun and of the Moon's phases.

A "votive tablet" found in the ruins of a Phoenician settlement in Sicily (Fig. 66a) depicts a scene in an open courtyard, suggesting that the Sun's movements rather than the night sky are the astronomical objective. The ringed pillar and an attar stand in front of a three-columned structure; there, too, is the viewing device: a ring between two short vertical posts placed on a horizontal bar and mounted atop a triangular base. This particular shape for observations of the Sun brings to mind the Egyptian hieroglyph for "horizon" - the Sun rising between two mountains (Fig. 66b). Figures 66a, 66b, 66c and 66d

Indeed, the Phoenician device (scholars refer to it as a "cult symbol") suggesting a pair of raised hands is related to the Egyptian hieroglyph for Ka (Fig. 66c) that represented the pharaoh's spirit or alter ego for the Afterlife journey to the abode of the Gods on the "Planet of millions of years." That the origin of the Ka was, to begin with, an astronomical instrument is suggested by an archaic Egyptian depiction (Fig. 66d) of a viewing device in front of a temple.

All these similarities and their astronomical origin should add new insights to understanding Egyptian depictions (Fig. 67) of the Ka's ascent toward the Gods' planet with outstretched hands that emulate the Sumerian device; it ascends from atop a pillar equipped with gradation-steps.

Figure 67

The Egyptian hieroglyph depicting this step-pillar was called Ded, meaning "Everlastingness." It was often shown in pairs, because two such pillars were said to have stood in front of the principal temple to the great Egyptian God Osiris in Abydos. In the Pyramid Texts, in which the pharaohs' afterlife journeys are described, the two Ded pillars are shown flanking the "Door of Heaven."

The double doors stay closed until the arriving alter ego of the king pronounces the magical formula:

And, soaring as a great falcon, the pharaoh's Ka has joined the Gods in Everlastingness. The Egyptian Book of the Dead has not reached us in the form of a cohesive book, assuming that a composition that might be called a "book" truly existed; rather, it has been collated from the many quotations from it that cover the walls of royal tombs.

But a complete book did reach us from ancient Egypt, and it shows that an ascent heavenward to attain immortality was deemed connected with the calendar. The book we refer to is the Book of Enoch, an ancient composition known from two sets of versions, an Ethiopic one that scholars identify as "1 Enoch," and a Slavonic version that is identified as "2 Enoch," and which is also known as The Book of the Secrets of Enoch.

Both versions, of which copied manuscripts have been found mostly in Greek and Latin translations, are based on early sources that enlarged on the short biblical mention that Enoch, the seventh Patriarch after Adam, did not die because, at age 365, "he walked with God" - taken heavenward to join the deity. Enlarging on this brief statement in the Bible (Genesis chapter 5), the books describe in detail Enoch's two celestial journeys - the first to learn the heavenly secrets, return, and impart the knowledge to his sons; and the second to stay put in the heavenly abode.

The various versions indicate wide astronomical knowledge concerning the motions of the Sun and the Moon, the solstices and the equinoxes, the reasons for the shortening and lengthening days, the structure of the calendar, the solar and lunar years, and the rule of thumb for intercalation. In essence, the secrets that were imparted to Enoch and by him to his sons to keep, were the knowledge of astronomy as it related to the calendar.

The author of The Book of the Secrets of Enoch, the so-called Slavonic version, is believed to have been (to quote R.H. Charles, The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament) "a Jew who lived in Egypt, probably in Alexandria" some time around the beginning of the Christian era. This is how the book concludes: Enoch was born on the sixth day of the month Tsivan, and lived three hundred and sixty-five years.

He was taken up to heaven on the first day of the month Tsivan and remained in heaven sixty days. He wrote all these signs of all creation which the Lord created, and wrote three hundred and sixty-six books, and handed them over to his sons. He was taken up [again] to heaveivon the sixth day of the month Tsivan, on the very day and hour when he was born.

Methosalam and his brethren, all the sons of Enoch, made haste

and erected an altar at the place called Ahuzan, whence and where

Enoch had been taken up to heaven. Not only the contents of the Book

of Enoch - astronomy as it relates to the calendar - but also the very

life and ascension of Enoch are thus replete with calendrical

aspects. His years on Earth, 365, are of course the number of whole

days in a solar year; his birth and departure from Earth are linked

to a specific month, even the day of the month.

Now that it is certain that the biblical tales of the Deluge and the Nefilim (the biblical Anunnaki), of the creation of the Adam and of Earth itself, and of ante-Diluvial patriarchs, are abbreviated renderings of original earlier Sumerian texts that recorded all that, it is almost certain that the biblical "Enoch" was the equivalent of the Sumerian first priest, EN.ME.DUR.AN.KI ("High Priest of the ME's of the Bond Heaven-Earth"), the man from the city Sippar taken heavenward to be taught the secrets of Heaven and Earth, of divination, and of the calendar.

It was with him that the generations of astronomer-priests, of Keepers of the Secrets, began. The granting by Min to the Egyptian astronomer-priests of the viewing device was not an extraordinary action. A Sumerian sculpture molded in relief shows a great God granting a hand-held astronomical device to a king-priest (Fig. 68). Figure 68

Numerous other Sumerian depictions show a king being granted a measuring rod and a rolled measuring cord for the purpose of assuring the correct astronomical orientation of temples, as we have seen in Fig. 54. Such depictions only enhance the textual evidence that is explicit about the manner in which the line of astronomer-priests began. Did Man, however, become haughty enough to forget all that, to start thinking he had attained all that knowledge by himself?

Millennia ago the issue was tackled when Job was asked to admit that not Man but El, "the Lofty One," was the Keeper of the Secrets of Heaven and Earth:

Have you ever ordered Morning or figured out Dawn according to the corners of the Earth? Job was asked. Do you know where daylight and darkness exchange places, or how snow and hailstones come about, or rains, or dew? "Do you know the celestial laws, or how they regulate that which is upon the Earth?"

The texts and depictions were intended to make clear that the human Keepers of the Secrets were pupils, not teachers. The records of Sumer leave no doubt that the teachers, the original Keepers of the Secrets, were the Anunnaki. The leader of the first team of Anunnaki to come to Earth, splashing down in the waters of the Persian Gulf, was E.A - he "whose home is water." He was the chief scientist of the Anunnaki and his initial task was to obtain the gold they needed by extracting it from the gulfs waters - a task requiring knowledge in physics, chemistry, metallurgy.

As a shift to mining became necessary and the operation moved to southeastern Africa, his knowledge of geography, geology, geometry - of all that we call Earth Sciences - came into play; no wonder his epithet-name changed to EN.KI, "Lord Earth," for his was the domain of Earth's secrets. Finally, suggesting and carrying out the genetic engineering that brought the Adam into being - a feat in which he was helped by his half sister Ninharsag, the Chief Medical Officer - he demonstrated his prowess in the disciplines of Life Sciences: biology, genetics, evolution.

More than one hundred ME's, those enigmatic objects that, like computer disks, held the knowledge arranged by subject, were kept by him in his center, Eridu, in Sumer; at the southern tip of Africa, a scientific station held "the tablet of wisdom." All that knowledge was in time shared by Enki with his six sons, each of whom became expert in one or more of these scientific secrets. Enki's half brother EN.LIL - "Lord of the Command" - arrived next on Earth.

Under his leadership the number of Anunnaki on Earth increased to six hundred; in addition, three hundred IGI.GI ("Those who observe and see") remained in Earth orbit, manning orbiting stations, operating shuttlecraft to and from spacecraft. He was a great spaceman, organizer, disciplinarian.

He established the first Mission Control Center in NI.IBRU, known to us by its Akkadian name Nippur, and the communication links with the Home Planet, the DUR.AN.KI - "Bond Heaven-Earth." The space charts, the celestial data, the secrets of astronomy were his to know and keep. He planned and supervised the setting up of the first space base in Sippar ("Bird City"). Matters of weather, winds and rains, were his concern; so was the assurance of efficient transportation and supplies, including the local provision of foodstuffs and the arts and crafts of agriculture and shepherding.

He maintained discipline among the Anunnaki, chaired the council of the "Seven who Judge," and remained the supreme God of law and order when Mankind began to proliferate. He regulated the functions of the priesthood, and when kingship was instituted, it was called by the Sumerians "Enlilship." A long and well-preserved Hymn to Enlil, the All Beneficent found among the ruins of the E.DUB.BA, "House of Scribal Tablets" in Nippur, mentioned in its one hundred seventy lines many of the scientific and organizational achievements of Enlil.

On his ziggurat, the E.KUR ("House which is like a mountain"), he had a "beam that searched the heart of all the lands." He "set up the Duranki," the "Bond Heaven-Earth." In Nippur, "a bellwether of the universe" he erected. Righteousness and justice he decreed. With "ME's of heaven" that "none can gaze upon" he established in the innermost part of the Ekur "a heavenly zenith, as mysterious as the distant sea," containing the "starry emblems... carried to perfection"; these enabled the establishment of rituals and festivals.

It was under Enlil's guidance that "cities were built, settlements founded, stalls built, sheepfolds erected," riverbanks controlled for overflowing, canals built, fields and meadows "filled with rich grain," gardens made to produce fruits, weaving and entwining taught. Those were the aspects of knowledge and civilization that Enlil bequeathed to his children and grandchildren, and through them to Mankind.

The process by which the Anunnaki imparted such diverse aspects of science and knowledge to Mankind has been a neglected field of study. Little has been done to pursue, for example, such a major issue as how astronomer-priests came into being - an event without which we, today, would neither know much about our own Solar System nor be able to venture into space.

Of the pivotal event, the teaching of the heavenly secrets to Enmeduranki, we read in a little-known tablet that was fortunately brought to light by W. G. Lambert in his study Enmeduranki and Related Material that Enmeduranki [was] a prince in Sippar, Beloved of Anu, Enlil and Ea. Shamash in the Bright Temple appointed him [as priest].

When the instruction of Enmeduranki in the secret knowledge of the Anunnaki was accomplished, he was returned to Sumer. The "men of Nippur, Sippar and Babylon were called into his presence." He informed them of his experiences and of the establishment of the institution of priesthood and that the Gods commanded that it should be passed from father to son:

According to the Sumerian King Lists Enmeduranna was the seventh pre-Diluvial holder of kingship, and reigned in Sippar during six orbits of Nibiru before he became High Priest and was renamed Enmeduranki.

In the Book of Enoch it was the archangel Uriel ("God is my light") who showed Enoch the secrets of the Sun (solstices and equinoxes, "six portals" in all) and the "laws of the Moon" (including intercalation), and the twelve constellations of the stars, "all the workings of heaven." And in the end of the schooling, Uriel gave Enoch - as Shamash and Adad had given Enmeduranki - "heavenly tablets," instructing him to study them carefully and note "every individual fact" therein. Returning to Earth. Enoch passed this knowledge to his oldest son, Methuselah.

The Book of the Secrets of Enoch includes in the knowledge granted Enoch "all the workings of heaven, earth and the seas, and all the elements, their passages and goings and the thunderings of the thunder; and of the Sun and the Moon; the goings and changings of the stars; the seasons, years, days, and hours."

This would be in line with the attributes of Shamash - the God whose celestial counterpart was the Sun and who commanded the spaceport, and of Adad who was the "weather God" of antiquity, the God of storms and rains. Shamash (Utu in Sumerian) was usually depicted (see Fig. 54) holding the measuring rod and cord; Adad (Ishkur in Sumerian) was shown holding the forked lightning.

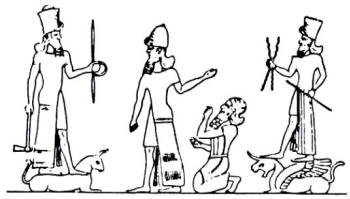

A depiction on the royal seal of an Assyrian king (Tukulti-Ninurta I) shows the king being introduced to the two great Gods, perhaps for the purpose of granting him the knowledge they had once given to Enmeduranki (Fig. 69). Figure 69

Appeals by later kings to be granted as much "Wisdom" and scientific knowledge as renowned early sages had possessed, or boasts that they knew as much, were not uncommon. Royal Assyrian correspondence hailed a king as "surpassing in knowledge all the wise men of the Lower World" because he was an offspring of the "sage Adapa." Another instance had a Babylonian king claim that he possessed "wisdom that greatly surpassed even that contained in the writings that Adapa had composed."

These were references to Adapa, the Sage of Eridu (Enki's center in Sumer), whom Enki had taught "wide understanding" of "the designs of Earth" - the secrets of Earth Sciences. One cannot rule out the possibility that, as Enmeduranki and Enoch, Adapa too was the seventh in a line of sages, the Sages of Eridu, and thus another version of the Sumerian memory echoed in the biblical Enoch record.

According to this tale, seven Wise Men were trained in Eridu, Enki's city; their epithets and particular knowledge varied from version to version. Rykle Borger, examining this tale in light of the Enoch traditions ("Die Beschworungsserie Bit Meshri und die Himmelfahrt Henochs" in the Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 33), was especially fascinated by the inscription on the third tablet of the series of Assyrian Oath Incantations. In it the name of each sage is given and his main call on fame is explained; it says thus of the seventh: "Utu-abzu, he who to heaven ascended."

Citing a second such text, R. Borger concluded that this seventh sage, whose name combined that of Utu/Shamash with the Lower World (Abzu) domain of Enki, was the Assyrian "Enoch." According to the Assyrian references to the wisdom of Adapa, he composed a book of sciences titled U.SAR d ANUM d ENLILA - "Writings regarding Time; from divine Anu and divine Enlil."

Adapa, thus, is credited with writing Mankind's first book of astronomy and the calendar. When Enmeduranki ascended to heaven to be taught the various secrets, his patron Gods were Utu/Shamash and Adad/Ishkur, a grandson and a son of Enlil. His ascent was thus under Enlilite aegis. Of Adapa we read that when Enki sent him heavenward to Anu's abode, the two Gods who acted as his chaperons were Dumuzi and Gizzida, two sons of Ea/Enki.

There, "Adapa from the horizon of heaven to the zenith of heaven cast a glance; he saw its awesomeness" - words reflected in the Books of Enoch. At the end of the visit Anu denied him everlasting life; instead, "the priesthood of the city of Ea to glorify in future" he decreed for Adapa. The implication of these tales is that there were two lines of priesthood - one Enlilite and one Enki'ite; and two central scientific academies, one in Enlil's Nippur and the other in Enki's Eridu.

Both competing and cooperating, no doubt, as the two half brothers themselves were, they appear to have acquired their specialties. This conclusion, supported by later writings and events, is reflected in the fact that we find the leading Anunnaki having each their talents, specialty, and specific assignments. As we continue to examine these specialties and assignments, we will find that the close relationship of temple-astronomy-calendar was also expressed in the fact that several deities, in Sumer as in Egypt, combined these specialties in their attributes.

And since the ziggurats and temples served as observatories - to determine the passage of both Earthly and Celestial Times - the deities with the astronomical knowledge were also the ones with the knowledge of orienting and designing the temples and their layouts. "Say, if thou knowest science; Who hath measured the Earth, that it be known? Who hath stretched a cord upon it?"

So was Job asked when called upon to admit that God, not Man, was the ultimate Keeper of the Secrets. In the scene of the introduction of the king-priest to Shamash (Fig. 54), the purpose or essence of the occurrence is indicated by two Divine Cordholders. The two cords they stretch to a ray-emitting planet form an angle, suggesting measurement not so much of distance as of orientation.

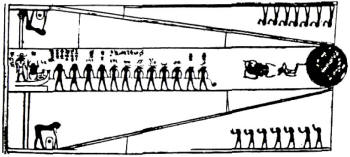

An Egyptian depiction of a similar motif, a scene painted on the Papyrus of Queen Nejmet, shows how two cordholders measured an angle based on the planet called "Red Eye of Horus" (Fig. 70). Figure 70

The stretching of cords to determine the proper astronomical orientation of a temple was the task of a Goddess called Sesheta in Egypt. She was on the one hand a Goddess of the Calendar; her epithets were "the great one, lady of letters, mistress of the House of Books" and her symbol was the stylus made of a palm branch, which in Egyptian hieroglyphs stood for "counting the years." She was depicted with a seven-rayed star within the Heavenly Bow on her head. She was the Goddess of Construction, but only (as pointed out by Sir Norman Lockyer in The Dawn of Astronomy) for the purpose of determining the orientation of temples.

Such an orientation was not haphazard or a matter left to guesswork. The Egyptians relied on divine guidance to determine the orientation and major axis of their temples; the task was assigned to Sesheta. Auguste Mariette, reporting on his finds at Denderah where depictions and inscriptions pertaining to Sesheta were discovered, said it was she who "made certain that the construction of sacred shrines was carried out exactly according to the directions contained in the Divine Books."

Determining the correct orientation called for an elaborate ceremony named Put-ser, meaning "the stretching of the cord." The Goddess sank a pole in the ground by hammering it down with a golden club; the king, guided by her, sank another pole. A cord was then stretched between the two poles, indicating the proper orientation; it was determined by the position of a specific star. A study by Z. Zaba published by the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences (Archiv Orientalni, Supplement 2, 1953) concluded that the ceremony revealed knowledge of the phenomenon of precession, and thus of the zodiacal division of the celestial circle.

The astral aspects of the ceremony have been made clear by relevant inscriptions, as the one found on the walls of the temple of Horus in Edfu. It records the words of the pharaoh:

In another instance concerning the rebuilding of a temple in Abydos by the Pharaoh Seti I, the inscription quotes the king thus:

The ceremony was pictorially depicted on the temple's walls (Fig. 71). Figure 71

Sesheta was, according to Egyptian theology, the female companion and chief assistant of Thoth, the Egyptian God of sciences, mathematics, and the calendar - the Divine Scribe, who kept the Gods' records, and the Keeper of the Secrets of the construction of the pyramids.

As such, he was the foremost Divine Architect.

|