|

by Tomas Frejka

December 04,

2017

from

N-IUSSP Website

Overestimates of population growth

are

fraudulent.

Google returns

7.5 million results for the word 'overpopulation',

all of which are ignorant, if not outright

fraudulently claiming that population is the blame

for everything.

Here is a

typical propaganda statement:

Human

overpopulation is among the most pressing

environmental issues, silently aggravating the

forces behind global warming, environmental

pollution, habitat loss, the sixth mass

extinction, intensive farming practices and the

consumption of finite natural resources, such as

fresh water, arable land and fossil fuels, at

speeds faster than their rate of regeneration.

Population

fear-mongering is a total fraud, similar

to global warming,

used to drive

the U.N.'s

Sustainable Development agenda.

Source

Half the

world's population reaching below replacement fertility

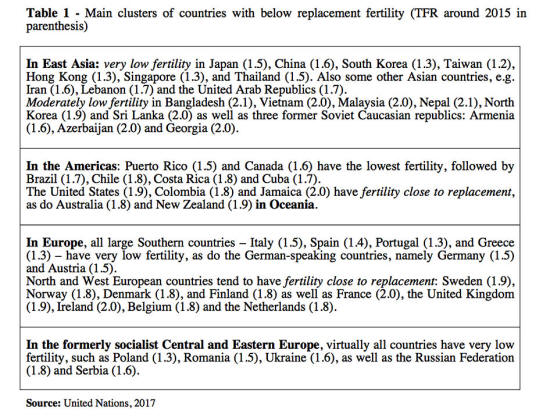

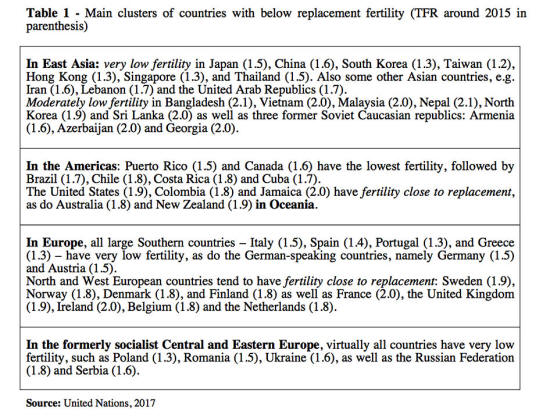

According to the

most recent UN estimates (United Nations 2017), almost one half of

the world's population lives in countries with below replacement

fertility (BRF),

i.e. with a total fertility rate (TFR)

below 2.1 births per woman.

Of these, one

quarter have TFRs close to the replacement level, i.e. between 1.8

and 2.1; the other three-quarters have really low fertility, below

1.8 births per woman.

Low-fertility

countries are generally grouped into clusters.

The main clusters

are in,

In fact,

contemporary fertility around the globe is lower than it has ever

been.

Since the middle of

the 20th century, childbearing has declined by 50

percent:

50 to 60 years

ago women in developed and developing countries combined had on

average 5 children, but now the world average is about 2.5

children per woman.

Why do so many countries

have below replacement fertility?

Early in the 20th century it became obvious that family

size was declining in countries experiencing substantial industrial

and urban growth.

A number of French,

British and American social scientists set out to map and explain

this change. Perhaps the most comprehensive and profound

explorations were conducted by a team of scholars at Princeton

University's Office of Population Research.

Frank Notestein,

its first director, outlined what had transpired by mid-20th

century, including the main causes for the changing family size, in

two papers dealing with what is now known as the "demographic

transition" (Notestein 1945 and 1953).

Much of the

following summary applies even today:

The new ideal

of the small family arose typically in the urban industrial

society. It is impossible to be precise about the various causal

factors, but apparently many were important.

Urban life

stripped the family of many functions in production,

consumption, recreation, and education. In factory employment

the individual stood on his own accomplishments.

The new

mobility of young people and the anonymity of city life reduced

the pressures toward traditional behavior exerted by the family

and community.

In a period of

rapidly developing technology new skills were needed, and new

opportunities for individual advancement arose.

Education and a

rational point of view became increasingly important. As a

consequence the cost of child-rearing grew and the possibilities

for economic contributions by children declined.

Falling death

rates at once increased the size of the family to be supported

and lowered the inducements to have many births.

Women,

moreover, found new independence from household obligations and

new economic roles less compatible with child-rearing.

(Notestein

1953:17)

Since then,

fertility trends and levels, and their causes and consequences have

been the most researched topics in population studies.

However, despite

the hundreds of published studies, it appears that Notestein's

observation continues to be valid:

"it is

impossible to be precise about the various causal factors, but

apparently many were important".

In addition to,

-

never-ending advances in technology

-

the

continuous need for new skills

-

the

indispensable need for education

-

the

persisting rise in costs of childrearing

-

continued

mortality decline

-

the steady

rise in women's status,

...important

causal factors generating contemporary BRF since around the 1960s

appear to be weakening economic and social conditions for large

swaths of the population.

These include often

imperfect social and family policy measures; the improving quality,

variety, and access to means of birth regulation; and the gender

revolution (Frejka 2017).

In the West, consisting of,

-

Western,

Southern and German-speaking Europe

-

North

America

-

Japan

-

other East

and South-East Asian countries,

...economic

and social conditions are not as favorable as in the post-Second

World War period.

Various beneficial

aspects of the "welfare state" have been whittled away. The level of

real income has been stagnating, and

income inequality increasing.

Employment levels

have been fluctuating. Unemployment among young people has been

relatively high and employment insecurity is widespread. The cost of

housing has been increasing, making it difficult for young people to

secure decent homes.

All of these

conditions have contributed to the fact that young people are short

on means and have postponed marriage and childbearing (Cherlin 2014,

Hobcraft & Kiernan 1996).

On the cusp of the 1990s, formerly socialist Central and East

European countries experienced a fundamental transformation from

paternalistic conditions of relatively secure employment, low-cost

housing, free education, free health care and various family

entitlements to the economic and social conditions of contemporary

capitalism just described above.

The concomitant

decrease in fertility and family size comes as no surprise (Frejka

and Gietel-Basten 2016).

In China, the strictly enforced one-child policy on top of

extraordinarily rapid industrialization and urbanization was

instrumental in lowering childbearing.

In all these countries, women have entered paid employment in vast

numbers, especially since the 1950s, shouldering not only household

chores, childbearing and childrearing, but also securing a

significant part of family income.

Often the needs of

the family and work collide, taking a toll on childbearing. Men have

started to contribute to household chores and childrearing, but only

in part and at a slower pace than women entering the "public

sphere."

As a whole, these

developments constitute what is known as the gender revolution

(Frejka et al. 2017).

The improved availability of a widening range of contraceptive means

- often labeled as the contraceptive revolution - and the

gradual legalization of induced abortions in many countries along

with safer methods of performing abortions have made it easier for

people to achieve whatever their desired family size might be.

Consequences of below

replacement fertility

Knowledge about the demographic consequences of fertility trends is

among the most important basic ingredients for long-term and

short-term policy making and planning.

Nowadays fertility

and its effects can be projected reasonably well for the near future

of 10-15 years, but also over longer periods, for which a set of

alternative projections can be calculated.

Such information is

indispensable for planning and costing educational institutions,

health care systems and social security systems, for example. It

also serves to determine the availability of human resources for the

labor market or for military purposes, or to calculate immigration

and emigration probabilities.

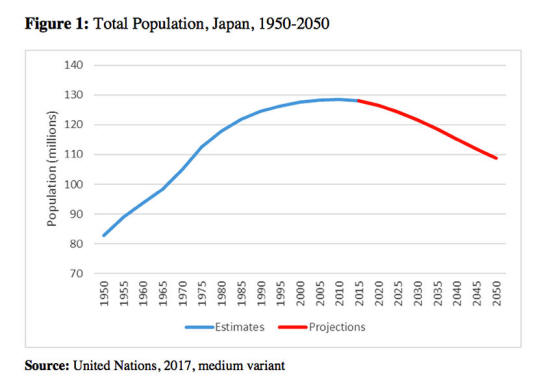

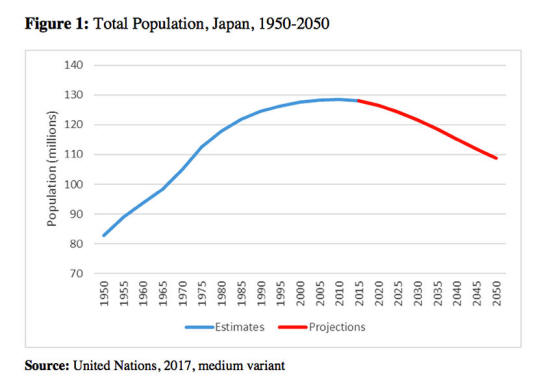

Let us take the example of Japan which is a relatively closed

population without much migration, in or out. Fertility declined to

below replacement in the late 1970s, and is currently at about 1.4

births per woman.

Because of

population momentum, the Japanese population was still growing until

around 2010, but it started to shrink thereafter and is likely to

continue to do so for decades (Figure 1).

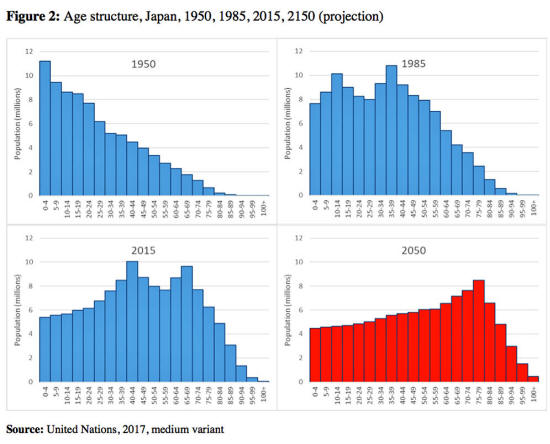

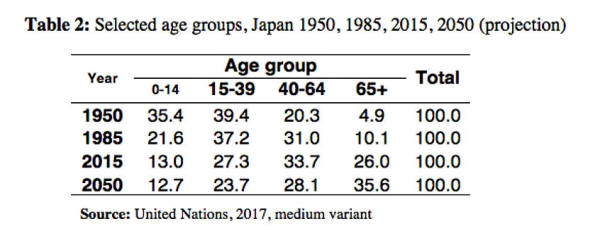

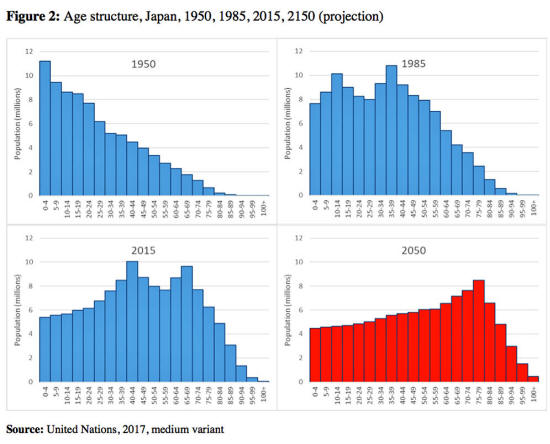

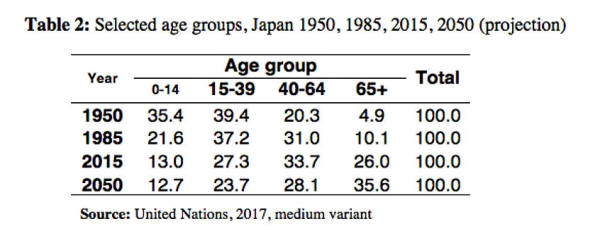

Changes in Japan's

age structure are depicted in Figure 2 and Table 2 for the years

between 1950 and 2050.

In 1950 the

majority of the population was young, and only 5 percent was 65

years old and over. By 2015 a full one quarter was aged 65 and over,

and by 2050 the proportion will likely rise to 36 percent.

The social and

economic costs of such an abrupt change in such a historically short

time are difficult to evaluate:

its impact on

the pension and health system, family structures, labor

productivity, etc. is enormous.

Japan, followed by

many other countries, is heading towards a path never experienced in

human history, and that appears to be full of unknowns.

Conclusion

Some may consider below replacement fertility and the ensuing

population decline as a positive development because it may lead to

a reduced need for, and to actual lower consumption of resources,

such as food, fuels, and housing (Grossman, 2017).

However, population

decline is necessarily accompanied by profound changes in the age

structure, and by a considerable increase in the share of old people

that, too, has its costs.

The general world trend is for a continued fertility decline and for

an increasing share of countries joining those with below

replacement fertility. When this decline is fast, profound or

prolonged, the consequences may be difficult to handle.

But this destiny is

not unavoidable:

a few

countries, especially in Northern Europe, which also experienced

a fertility decline, have been successful in maintaining levels

close to replacement.

So the good news is

that declining fertility may be stopped before it gets too low or

may even be reversed.

How that can be

done, however, may require another article in N-IUSSP.

References

-

Cherlin,

Andrew J. 2014. Labor's Love lost: The Rise and Fall of the

Working-Class Family in America. The Russell Sage

Foundation.

-

Frejka,

Tomas. 2017. "The fertility transition revisited: A cohort

perspective," Comparative Population Studies, 42:89-116.

-

Frejka,

Tomas and Stuart Gietel-Basten. 2016. "Fertility and Family

Policies in Central and Eastern Europe after 1990."

Comparative Population Studies. 41 (1): 3-56.

-

Frejka,

Tomas, Frances Goldscheider and Trude Lappegård. 2017. "The

Two-part Gender Revolution, Women's Second Shift and

Changing Cohort Fertility." Stockholm Research Report in

Demography. SSRD 2017:23

-

Grossman,

Richard. 2017. The world in which the next 4 billion people

will live. N-IUSSP

-

Hobcraft,

John and Kathleen Kiernan. 1995. "Becoming a parent in

Europe." In: European Population Conference 1995. Evolution

or Revolution in European Population. Vol. 1. Plenary

Sessions. Milano. 27-65.

-

Notestein,

Frank W. 1945. "Population - The Long View." in Schultz,

Theodore W. ed. 1945. Food for the World. 36-57.

-

Notestein,

Frank W. 1953. "Economic Problems of Population Change." In

Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference of

Agricultural Economists. New York. 13-31.

-

United

Nations. 2017. World Population Prospects: The 2017

Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables. ESA/P/WP/248.

|