by Marc Ambinder

April 11, 2011

from

NationalJournal Website

|

The White House is prepared for

another catastrophe.

But the rest of the government is not

prepared for what comes next. |

On the morning of

September 11, 2001, after terrorists

toppled the World Trade Center towers, rammed a jet into the Pentagon, and

were thought to be in control of an unknown number of additional planes, the

National Security Council ordered the government to act as if the apocalypse

was now.

A series of secret orders, known collectively as

Continuity of Government, or

COG, zipped across the government’s classified computer and phone

networks.

On cue, the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Alternate National Warning

Center in Olney, Md., sent emergency action alerts. The 1st

Helicopter Squadron (code-named “Mussel”) swooped down to the National Mall

from Andrews Air Force Base, grabbed congressional leaders, and rushed them

to the

Mount Weather Emergency Operations Center

in Bluemont, Va.

The Secret Service spirited first lady Laura

Bush to a bunker beneath one of its buildings. An Army helicopter on standby

at Davison Army Airfield, about 15 miles from the Pentagon, whisked the

deputy Defense secretary, Paul Wolfowitz, to an enormous hardened bunker

(code-named “Marconi”) deep within the

Raven Rock Mountain Complex near Maryland’s

border with Pennsylvania.

But 50 years of secret contingency planning, most of it drawn up with a

U.S.-Soviet Union nuclear war in mind, had not anticipated a threat like the

one that came on 9/11. No one had updated continuity-of-government plans for

the Pax Americana. Communication nodes malfunctioned, leaving

President Bush, who was in Florida, out of touch with the military and the

White House at key points during the day.

Hotlines, conference-call systems, and telephone

circuits with built-in preemption capability - the key connections between

all the moving parts - were unreliable.

The government couldn’t find Cabinet members; they and their security

details were clueless about where to go. The Presidential Emergency

Operations Center, or

PEOC, three stories beneath the East Wing of the White

House, was not always in contact with the president when it needed to be.

For a time, the emergency center could not reach Defense Secretary Donald

Rumsfeld, who was assisting with the rescue operations at the

Pentagon, even though an officer or two from the Pentagon Communication

Agency accompanied his personal protection detail.

That day did not cause an existential crisis for American government. The

evacuation of key leaders from Washington worked well enough. But the

problem was distilled by a furious phone call from

Bush to PEOC at 10:08

a.m. demanding to know what the hell was going on. Fact is, the people there

didn’t really know and weren’t equipped to find out.

Eventually, officials realized they had a major national-security threat

that was independent of terrorism: Any major catastrophe in Washington could

bring down the federal government, blurring chains of command and separating

decision makers from intelligence.

And if something truly catastrophic happened,

they acknowledged, they would have no idea how to reconstitute government

afterward.

PREPARING FOR THE

WORST

Months before

September 11, riding in a routine springtime motorcade in

Washington, Bush had tried to make a telephone call from his limousine.

Static. He couldn’t get a signal.

When he arrived at the White House, he pointed

to Joseph Hagin, his deputy chief of staff for operations - the man

responsible for making the president go - and motioned him over.

In no uncertain terms, Bush told Hagin that the

president should be able to make a telephone call to anyone at any time.

“He essentially said to me, ‘We need to fix

this and fix it quickly.’ He asked, ‘What would we do if something

really serious happened and this didn’t work?’ ”

For the next seven years, Hagin led an extremely

secret, multibillion-dollar effort to reconstitute the nation’s doomsday

plans. He has never before given a formal interview on the subject.

Hagin had not finished the job by September 11. The day after, at a National

Security Council meeting, Bush was “irate,” as one aide put it, about the

failure in communication that caused the breakdown in the chain of command.

To this day, senior members of the NSC do not know whether Bush gave Vice

President Dick Cheney the authority to order planes shot down, as

Cheney asserted.

(Bush later said he did, in a conversation

between the two before 10 a.m., but no evidence exists, and many members of

the administration suspect that Bush gave Cheney no such blessing, though

none would say so on the record.)

The 9/11 commission, which was established to

prepare a full account of the circumstances surrounding the terrorist

attacks, including the government’s preparedness and response, noted only

that the president’s and vice president’s recollections did not necessarily

jibe with the notes taken by others who were with both men that morning.

After the attacks, Hagin refocused his work to head off this sort of

communications dysfunction in the next crisis. The goal: Move information to

the president immediately - anywhere, regardless of place or time - about

threats to the homeland. If the president couldn’t be reached, the Defense

secretary had to be available to make decisions.

The president could delegate his authority to

the vice president - but Bush wanted to have the option to do so or not,

something that aides got the strong impression he had not had on September

11 when Cheney jumped in decisively. No one blamed Cheney, who was steeped

in Reagan-era continuity planning, but they recognized that the legitimacy

of the presidency was at stake if the vice president had to improvise.

What if the president needed to decide on a

nuclear attack but couldn’t be reached?

“[Bush] said to me, ‘We need to fix this and

fix it quickly.’ ”

- Joseph Hagin, former White House deputy

chief of staff for operations

“We worked quickly to reduce the time it

took to get the president ready to make a call for Noble Eagle events,”

a former Bush administration official told National Journal, referring

to the combat air-patrol canopy over Washington.

If a plane were to violate the air-defense zone,

the president would receive instant briefings and could be connected to the

National Military Command Center within minutes.

Officials updated the technology of the

nuclear-launch briefcase, the so-called football, and revised its

accompanying folders to include contingency responses to a range of

disasters.

The U.S. Northern Command, or

Northcom, was launched in 2003 to oversee the

defense of the country’s interior; it also took responsibility for the

combat air patrols over Washington and for several units that perform

classified missions related to homeland defense. Northcom, headquartered at

the District of Columbia’s Fort McNair, was given shoot-down authority for

airplanes across the country.

Working with the Energy Department, Northcom monitors a real-time radiation

map of the Washington metropolitan area; almost every day, a department

helicopter flies over sensitive areas to determine if the background levels

have changed.

Karl Horst, the commanding general of Joint

Force Headquarters for the National Capital Region, told National Journal

that,

Northcom is responsible for the antimissile batteries around Washington

and for evacuating the government in catastrophic circumstances - by air, by

ground, and by sea.

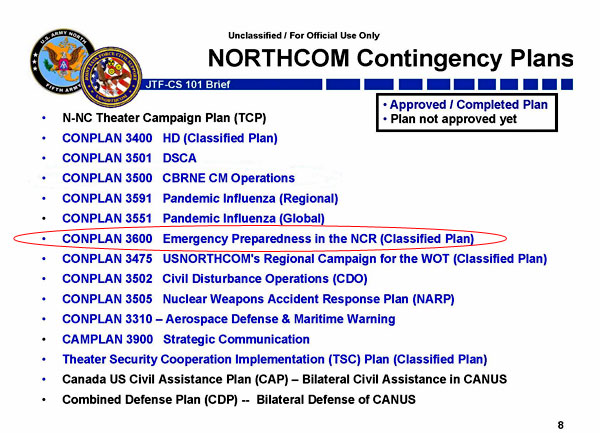

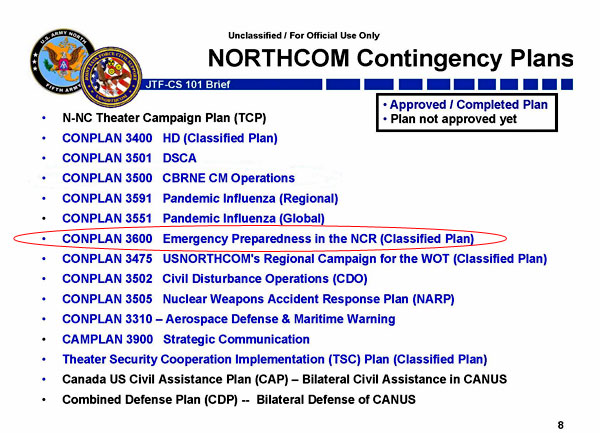

A classified Concept of Operations plan known as

Conplan

3600 spells out these functions.

http://www.npstc.org/meetings/IO-Barber-JTFCS

101 Brief-readahead-20081119.pdf

For spiriting officials away, the government has more than a half-dozen

command posts built into airplanes and more than a dozen transportable

systems on the ground.

Plans call for potentially stashing officials on

submarines, aircraft carriers, and offshore bases - even in friendly foreign

countries. Budget requests boosted the Secret Service’s budget by several

hundred million dollars for emergency capabilities.

The military established a second alternate

command center on a base near the White House and a third bunker at the

Pentagon.

It took several years and several hundred billion dollars to modernize the

communications links between the president, the Cabinet, the military, and

the bunkers - known informally as “the sites.” A number of redundant

networks were put in place, run by a little-known agency called the National

Communications System.

Located in the Homeland Security Department, it

manages a variety of secret projects, including one called SRAS, or Special

Routing Arrangement Service, which gives government officials priority use

of our communications systems in emergencies and acts as a hub to transmit

emergency war orders. The National Security Council and the White House

Military Office also manage a system of interlinked and redundant

communications bunkers across the country that allow the president to

communicate directly with, say, the director of the CIA or the FBI, wherever

they are.

Hagin’s team modernized presidential relocation facilities, including the

White House’s PEOC and the Raven Rock bunker that served as Cheney’s

“undisclosed location.”

Officials reopened several closed bunkers and

constructed new ones in Colorado and Florida. Altogether, about a dozen

formal presidential relocation facilities are stocked with six months’ worth

of supplies. National Journal discovered a secret Defense Department agency

responsible for COG acquisitions - the folks who make sure the bunkers have

toilet paper. (The National Security Council asked NJ not to reveal its name

because doing so would jeopardize the cover programs associated with other

COG functions.)

The agency operates out of a nondescript office

building in Maryland.

It took two years to equip the president’s limousine with reliable, secure

voice links to Royal Crown, the White House’s switchboard for classified

communications. In 2004, Air Force One finally received teleconferencing

capability - and live TV. The White House Communications Agency upgraded its

Washington-area infrastructure and spent several years reconciling

interoperability issues with the Secret Service.

The communications agency surveyed major telecom

carriers and found that one had much more capacity than the others; everyone

got new phones. (National Journal was asked not to disclose the carrier.)

Many of the assets that

FEMA uses to mitigate and respond to disasters have

classified functions that kick in when COG plans are executed. The number of

programs is secret, but the government has secure facilities at every

Cabinet headquarters and relocation site that contain protected vaults

stocked with bright red binders. The binders spell out the COG plans for the

department.

The security officers who guard the vaults and

safes are paid by their departments, but they actually report to the White

House Military Office.

Presidential helicopters are a weak link in the chain of command.

Officially, the

HMX-1 squadron, based in Quantico, Va., has at least 17

working helicopters. The reality is that a large number are used for spare parts.

The copters are 30 years old, and President Obama killed a follow-on program

because it was more than $1 billion over budget.

Back when Bush was on board, the helicopters

experienced two power failures and one communications breakdown. Designed

for 14 passengers, many of the choppers seat only 10 because of bulky

emergency communication equipment and countermeasures. (The Secret Service,

which supervises presidential COG programs, declined to comment, and the

Marine Corps referred requests for comment to the White House.)

A White House official said that

Obama endorses

a reasonably priced alternative and that it is on track.

The secret COG apparatus is huge: One former government official with

knowledge of the budget estimates that continuity-of-government programs

have cost $20 billion over the past 10 years. When Obama took office, he

asked for a full accounting.

A six-month study concluded that although the

COG expansion made it much likelier that the president and the Cabinet

members could be safely hidden and protected, the plans did not sufficiently

address what happened next - when Cabinet secretaries had to figure out how

to respond to a paralyzing

influenza pandemic, for example.

-

Would state governments follow federal

orders?

-

Would private companies allow the

executive branch to take over their operations and carry out orders?

-

Who had the telephone numbers of the

superintendents of major school districts so that the president

could call and personally request that a system be shut down if a

state refused to do so?

Obama has kept the COG infrastructure intact for

now. According to administration officials, he has also pushed to link its

functions with the rest of the government’s catastrophe planning.

Last year, the administration held what it

called the biggest continuity-of-government exercise since September 11; top

White House officials were evacuated, as were members of the Cabinet and

their senior aides.

“The goal was to see how we could all get

off-site and still communicate,” a senior official said. Obama

participated from the White House Situation Room.

An annual tabletop exercise called Eagle

Horizon, which envisions multiple simultaneous catastrophes, included more

participants in 2010 than any other exercise of its kind before, according

to a FEMA official.

Hagin said he did not intend to criticize the Obama administration, and he

informed the NSC about his cooperation with National Journal. But he also

told NJ that he observes a sense of drift in all branches of government as

the passage of time since September 11 draws focus from emergency

preparedness.

He worries that COG programs, which have large

but classified budgets, face pressure to slash spending.

“The continuity-of-government programs took

on an urgency [on September 11] that they certainly had not held since

the fall of the Berlin Wall and possibly at any time since the Cuban

missile crisis,” Hagin told National Journal.

No matter the cost, the Bush administration was

determined to take them seriously.

It was forced to.

SEPARATION OF POWERS

Decapitation attacks from terrorists or natural disasters that could

paralyze Washington are low-probability, high-impact events. It’s hard to

protect against them, let alone figure out how to pay for those protections.

Resources are finite. When a military asset is

deployed as a backup communication system to another backup communication

system on the chance that an improbable event might happen, that asset is

not available to support troops in actual combat. These are legitimate

trade-offs that should be debated.

Yet, by definition, very few people have a bird’s-eye view of the COG

programs from which to debate them. And because they are enmeshed in

questions about the Constitution and the separation of powers, Congress has

very little oversight for them. The National Security Council controls these

“Special Access Programs,” and virtually everything about them is orally

briefed to a few select members of Congress.

Not even the chairs of the Homeland Security

committees are privy to all the details. Consequently, almost no debate

about COG takes place - how much it costs and what assumptions govern its

implementation. And it is not even clear which branch of government should

have authority over continuity of government.

In 2007, Bush issued a homeland-security presidential directive that

consolidated COG functions in the White House because FEMA was having

trouble interacting with the Defense Department on crucial, classified

issues. That directive also established, in public, the dual assumptions

that guided Bush’s planning.

The branches, led by the executive, would work

together to prepare for catastrophes, but the executive branch would

exercise unilateral authority to make sure that eight “national essential

functions” - from “providing leadership visible to the nation and the world”

to stabilizing the economy - continued to operate throughout a major

emergency.

Read one way, the directive implies that, in an emergency, the executive

branch has the authority to ignore Congress and the judiciary if it wants

to. The body of law that governs national emergencies can certainly be

interpreted that way.

Many statutes and unclassified orders expand the

authority of the military to carry out executive functions that amount to

martial law (contravening the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, which restricts

what the military can do on American soil).

The directives even spell out what happens if someone lower in the line of

succession takes advantage of uncertainty to assume presidential authority.

Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin Roosevelt, allows the

military to establish operational zones inside the United States during

emergencies. Nixon’s Executive Order 11490 allows for the emergency “control

of enemies and other aliens” within U.S. borders - and for the Securities

and Exchange Commission to shut down the stock markets.

The

National Emergencies Act in 1976 gives the

president broad powers that the Army believes allow the commander in chief

to,

“regulate the operation of private

enterprise, restrict travel, and, in a variety of ways, control the

lives of United States citizens,” according to a 2010 Army legal

document obtained by National Journal.

Then there’s the

Insurrection Act, which gives

the president the power to use the military to forcibly contain “civil

disturbances.”

The rules of engagement are classified but

“restrictive in nature,” according to the Army document. An “execute order”

issued by the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 2009 lays out some

scenarios in which the military can use force, even without permission from

higher authorities - usually when no federal law-enforcement officials are

available, and lives and property are in imminent danger.

The military can even make arrests under those circumstances, under

10 USC

382.

Title 10, Section 374 (b) 2 of the U.S. code

permits the Defense Department to provide technological and personnel

support to law-enforcement agencies. Under Title 18 of the code, the

attorney general can request significant military assistance for containing

and mitigating civil disturbances.

Other laws permit emergency quarantines, too.

The most sensitive parts of continuity of government - the ones that expand

executive power most conspicuously - are very closely held. They’ve been

completely revised, according to several officials who have read them, for

an era when state governments feel confident exercising their own power and

when some Americans are predisposed to suspect martial-law scenarios.

Classified executive orders spell out a range of

powers the president can assume in the event of an incident of national

significance. (Since 1958, one of these documents has provided for the

suspension of habeas corpus for citizens on “security” lists at the time of

a crisis.)

According to people who have seen them, the COG plans include draft

presidential emergency-action directives, or

PEADs, under which White House

lawyers can fill in the blanks - in the case of “x,” the president may do

“y.” But it’s unclear whether, during an emergency, these orders would be

recognized by the federal agency or officials they’re directed to, or by

state governments, or even by the American people.

The Bush-era COG plans were based on the

commonsense premise that no post-disaster government would be legitimate

unless people perceived it to be a valid expression of their will and the

constitutional balancing of powers among the branches. The Bush White House

encouraged the federal branches to plan together.

The COG plans also include, however, directives for scenarios in which one

or two branches of government cannot function.

“As we would go through functions, we would

realize, ‘Oh shit, that’s going to be a challenge because Congress can’t

constitute a quorum,’ ” one of Hagin’s colleagues said.

“So our plans were written from an

operational concern about our ability to perform their role, and what

flows from the executive branch in those situations is the scenario

where they can’t [perform].”

LEGITIMACY

COG planners are particularly worried about how to reconstruct a government

whose authority people will respect. That wasn’t a problem when President

Truman first confronted the prospect of a nuclear doomsday.

During his presidency, military officers wrote

plans for a post-crisis government that the public would almost certainly

have accepted as legitimate. People of that era did not conceive of a

six-decade-long diminution of trust in the presidency - or in all large

institutions. They did not consider the idea that a malfunctioning Congress

could affect the way Americans respond to emergency powers because no one

would be able to check the president.

Back then, functions mattered more than

personality. That is, if the president were killed, it would be sufficient

that his successor (whoever that might be) could press the right buttons to

launch nuclear weapons.

By September 11, 2001, that 1940s-era system was inadequate because the

world had calmed down. The idea that terrorists could decapitate the

government was within the realm of imagination, but it was not something

that preoccupied Washington.

CIA Director Leon Panetta, who was President

Clinton’s chief of staff, told National Journal that he recalls being

introduced to the bunker facilities underneath the White House and

participating in a few exercises, but says he had no cause to spend much

time on continuity-of-government scenarios.

Meanwhile, the plans themselves were relics. Most were minor revisions to

the Eisenhower administration’s Code of Emergency Federal Regulations

blueprints.

Those secret documents emphasized fixing

immediate problems like food shortages and rioting rather than ensuring that

legitimate elected officials could solve problems and mitigate the potential

for an extended crisis.

“I feel very confident that we can

reconstitute the legislative process.”

- Senate Sergeant-at-Arms Terrance Gainer

The

Presidential Succession Act of 1947 spells

out procedures to ensure that constitutional government endures, but it is

full of holes.

In the scenario imagined by the statute - no

president, no vice president, no speaker of the House, and no president pro

tempore of the Senate - the secretary of State becomes president either

until the end of the current president’s term in office or until someone

higher in the chain of command suddenly reappears or recovers from injuries

and is able to discharge the powers of office.

(After the secretary of

State, the chain of succession proceeds through the Cabinet, based on when

the departments were created.)

Imagine that some lower officeholder takes power for a time, and then the

vice president recovers from an injury. As soon as the VP wants, he or she

can “bump” the acting president - or not, if the VP doesn’t want to.

Constitutional scholars don’t like this

provision because it provides incentives for all sorts of mischief (someone

could be bumped just as a particular piece of legislation needed the

president’s signature) and relies on the assumption that national leaders

are willing to completely surrender the attachments of their political party

and their personal agenda.

Another problem is that, in a catastrophic emergency, the people who need to

know who is in charge might not be able to find this out immediately. In

particular, the Secret Service and the officials who execute lawful orders

from the National Command Authority (which is another name for the commander

in chief’s executive powers) might be paralyzed by a communications

breakdown, despite all the systems.

If confusion persists about who’s alive and

who’s dead - and if, for example, the Defense secretary and the chairman of

the Joint Chiefs of Staff are out of the country or incommunicado - the

confusion could be deadly.

Maybe the secretary of Defense, if he doesn’t have contact with anyone above

him in the chain of command, assumes that he is the acting president. Maybe

the vice president will do the same if he can’t reach the president, or if

the Secret Service doesn’t know whether the president is alive.

These are extremely unlikely scenarios, but what

happens if two people act as if they’re in control?

The PEADs provide Cabinet secretaries, White House aides, and other senior

officials with what amount to checklists:

Have you called here?

Have you

waited for “x” amount of time?

Are you sure that FEMA hasn’t done “y”?

After they answer the questions, the checklists

then empower the officials to temporarily assume certain presidential

authority to make sure that the government can function.

The directives even

spell out what happens if someone lower in the line of succession takes

advantage of uncertainty to assume presidential authority. The documents are written, essentially, to deal

with possible coups d’état.

These scenarios are improbable, but the confusion around them is not.

Confusion played out for real in 1981 during the attempted assassination of

President Reagan. In the chaos after the president was shot, Secretary of

State Alexander Haig declared that he was in charge. The secretary had

apparently forgotten that the vice president, the speaker of the House, and

the president pro tempore of the Senate were above him in the line of

succession.

(Haig later insisted that he meant to say that

he was in charge of just the White House and its immediate executive

functions until Vice President George H.W. Bush could return to Washington.)

Reagan’s “biscuit” - his nuclear-command code-verification card - remained

in the custody of the FBI for a period of time after the shooting, even

though Bush was connected to the National Military Command Center at all

times. There was no abrogation of the National Command Authority, and yet

the American people were treated to scenes that seemed to show an executive

branch out of control.

Possibilities like these keep planners up at night. Hagin and others believe

that an alive, alert, in-touch elected president of the United States will

have an enormous calming effect on the American people during a major

calamity.

But in an age where some people seem to doubt

the legitimacy of presidents even before they take office (Bush lost the

popular vote in 2000, and a quarter of Americans still think that Obama was

not born in the United States), it’s hardly clear that the public would

accept Vice President Joe Biden or Speaker John Boehner as chief executive.

Norman Ornstein of the

American Enterprise

Institute and other scholars believe that a government run by someone who is

unelected or someone without a Congress to provide a check wouldn’t be seen

as legitimate even if the levers of government worked.

WHOLE OF GOVERNMENT

In the end, continuity of government relies as much on the other two

branches of government as on the executive.

But the different habits and prerogatives of

each are difficult to bridge. Virtually every former and current official

contacted by National Journal is confident that the executive branch is well

prepared to handle almost anything. But they said that Congress and the

judicial branch might not be.

Hagin says he did what he could. He furnished the House speaker with a plane

containing secure communications, and he offered to help pay for judiciary’s

separate and unrelated “marshal’s office” - which protects Supreme Court

justices when they are outside the District as well as federal judges across

the country - to modernize its COG plans.

(Continuity-of-government planning

for justices and the Court itself is handled by this marshal’s office, which

did not return a phone call seeking comment.)

Ornstein has long complained about the American political system’s inability

to conceive of the questions that would arise if many members of Congress

were killed - or if Congress were unable to function at all.

Then there’s the problem of constitutional succession. The president pro

tempore of the Senate, who is customarily the longest-serving - and oldest -

member of the majority party, is fourth in line to the presidency. The

majority leader of the Senate, who is much more familiar with the policy

decisions that would need to be made in an emergency, is nowhere in the line

of succession.

Had a decapitation strike taken out Bush, Cheney, and the speaker of the

House in 2001, the octogenarian Sen. Robert Byrd, D-W.Va., would have become

president, and his staff could have taken over the government.

Currently, 86-year-old Sen. Daniel Inouye,

D-Hawaii, fills that post. Senior officials in the Bush and Obama

administrations say they have privately expressed concern to Senate Majority

Leader Harry Reid about the role of the president pro tempore. Reid has not

been responsive, these officials say. The majority leader’s office declined

to comment, but a simple Senate rules change could fix this quirk.

The Constitution itself is another problem. When a senator dies, the

appropriate state government usually acts quickly to appoint a successor,

but House seats remain vacant until a special election is held. After a

crisis, the Senate could reconstitute itself much more quickly than the

House could. If a catastrophe happened to wipe out most of Congress

tomorrow, Democrats would quickly be running Capitol Hill again.

The Republicans’ control of the House - if the

lower chamber were able to function at all - would be wiped away. According

to several congressional officials, members and their staffs pay little

attention to the subject of continuity.

But Terrance Gainer, the Senate sergeant-at-arms

and the former head of the U.S. Capitol Police, insists that the legislative

branch’s continuity-of-government planning is robust and dynamic.

“The notion that we aren’t prepared speaks

highly of the classified system that we have in place,” he said. The

plans are “well formed and well rehearsed,” Gainer said.

“Whether something happens to one building

on Capitol Hill, whether Washington, D.C., as a whole isn’t available to

us, whether it is something more catastrophic… I feel very confident

that we can reconstitute the legislative process.”

Gainer is briefed on COG planning at least once

every two weeks, he says, as is Phillip D. Morse, his counterpart at the

Capitol Police, which is responsible for the Capitol complex and the

security of the House of Representatives.

Their teams have rehearsed such nuances as how

to physically deliver legislation if the president is somewhere else.

“Our main goal is to make sure that Congress

can do substantive, meaningful legislation,” Gainer said.

Others briefed on Congress’s plans are

skeptical.

One official privy to recent congressional COG

plans said that members have never been subject to a call-tree exercise,

which is the staple of continuity planning.

“No one has ever sat down from a secure site

and tried to call every member of Congress in their districts to see the

response rate,” the official said. “I know it takes time to do this, and

I know that it’s not in the nature of Congress to be closed and

secretive about these things, but we have to do them.”

Speaker Boehner has asked his chief of staff,

Barry Jackson, who became familiar with COG plans as an official in the Bush

White House, to assess congressional readiness, a senior Republican aide

said.

In Ornstein’s assessment, the legislature’s

continuity-of-government planning is,

“a classic case of avoiding short-term

discomfort to insure against small chance of devastating long-term

catastrophe.”

“The farther we get away from September 11,” Hagin said, “the more

memories start to fade. No president, current or future, should want to

be in a position to struggle to communicate effectively because the

technology was not there in a critical national emergency. We learned

that the hard way, and we suffered through a time with an inadequate

system.”

On the night of 9/11, members of Congress

memorably gathered on the Capitol steps to sing “God Bless America.”

It was a sign to all that the Republic was

strong. But what if there is no Congress to gather and give that sign? The

legislative branch lags behind the executive branch in considering that

possibility.

The legitimacy of what the government

does in a crisis is at stake.

Doomsday Lingo - A Guide

by Marc Ambinder

April 8, 2011

from

NationalJournal Website

The secret world of Continuity of Government

planning has its own vocabulary and history. Acronyms are often meant to

obscure, rather than elucidate.

Here’s a brief primer:

-

NSPD 51/HSPD-20 - The National Security

and Homeland Security Presidential Directives that replace the

Clinton-era directive on the national continuity policy. The

directive pulls critical COG functions into the WHMO and contains

classified annexes.

-

COG - Continuity of

Government - six or more discrete classified programs designed to

safeguard the National Command Authority - the president and/or his

successors - during an attack and allow senior government officials

to communicate with each other to ensure that essential government

functions can be performed. The plans are so highly classified that

they are only revealed to Congressional leaders and a few chairs and

ranking members of relevant committees.

-

ECG - an effort,

originated by the

George H.W. Bush administration, to

link up the continuity plans of all three branches of government and

ensure that all can function properly. The goal of ECG is to

preserve constitutional democracy. Very little is known about ECG

plans, or whether ECG is merely a concept that informs certain COG

plans.

-

COP - Continuity of

the Presidency - a subcomponent of COG, COP plans, when executed,

trigger a surge of communication and security resources to protect

the sitting president's ability to function as the Commander in

Chief.

-

The Mountain - the colloquial term for

MWEOC, the

Mount Weather Emergency Operations Center

in Bluemont, Virginia. Mount Weather is widely known (but still not

officially acknowledged) to be a major relocation facility for

members of Congress, the Cabinet and the President.

FEMA operates an overt emergency

operations center on the premises. There's also a gift shop.

-

The Rock - the colloquial term term for

the enormous complex of bunkers and

communication towers at Raven Rock, near Waynesboro, PA., It's

the home to the Alternate Military Command Center and a presidential

bunker, among other tenants.

-

PRFs - Presidential

Relocation Facilities, a.k.a, secret underground bunkers. There are

a dozen in operation today.

-

PEADs -

Presidential Emergency Action Directives - executive orders that

grant or more precisely define presidential powers when a state of

emergency is declared pursuant to the National Emergencies Act of

1950. Most are classified.

-

COOP continuity of

operations - Since 2005, federal agencies performing "primary

mission essential functions (PMEFs)," have submitted extensive

internal contingency plans to FEMA and the White House. Twice a

year, agencies like the FBI run COOP drills, where headquarters

functions are relocated to an alternative site and procedures are

tested.

-

Defense Mobilization Systems Planning

Activity - established in 1982 to provide a "legit" cover for the

National Programs Office, which ran more than a dozen Reagan era COG

plans, most of which were kept from Congress, and some of which were

probably illegal. In 1994, the Clinton administration shut this

apparatus down and transferred core COG functions to FEMA and the

Defense Information Systems Agency.

-

Sensitive Support Operations - the

official DoD term for special circumstances when units that don't

exist perform emergency or continuity functions that you're not

supposed to know about, like Joint Special Operations Command

support to the Joint Terrorism Task Forces. Classified guidelines

describe how said authorities do not violate the

Posse Comitatus Act, which

prohibits the military from directly supporting law enforcement

agencies.

-

CONPLAN - Concept

of Operation Plan - basically, a plan.

-

OPLAN - what CONPLANS are called when

people are actually doing them

-

EXORDs - execute orders, temporary and

standing, that provide specific authorities under specific

circumstances

-

CONPLAN 2202-05 - the classified plan

that is operationalized when an enemy force invades or indigenously

appears on American soil.

-

CONPLAN 3500 series - Classified plans

relating to CBRNE mitigation inside the United States.

-

CONPLAN 3501-09 - a 500 page

unclassified operational plan that explains the various ways that

the Defense Department can support civilian agencies and provides

for the chain of command and legal authorities to do so.

-

CONPLAN 3502-07 - A classified plan,

informally known as GARDEN PLOT, that describes the way the military

will support civilian law enforcement agencies and the National

Guard during "civil disturbances," or riots.

GARDEN PLOT was activated in 1992

to quell the violence after the Rodney King verdict. The President

can trigger this plan when the National Guard is no longer

sufficient to contain a civil disturbance or after the executive

agent has given the rioters an ultimatum to disperse..

-

CONPLAN

3600 series - Classified NORTHCOM plans that delegate the Joint

Force Headquarters National Capital Region's roles and

responsibilities before, during and after a major emergency in the

NCR, including counter-terrorism, COG, hardening of the White House

complex and WMD consequence management.

-

CONPLAN 0300 series - Classified Joint

Chiefs of Staff plans involving counter-terrorism and support to

domestic law enforcement agencies. The unclassified nickname for

this series is

POWER GEYSER; the sub-plans have an

extra word added to them, like POWER GEYSER CUP or POWER GEYSER

TREE.

-

CONPLAN 0400 series - Classified JCS

plans dealing with domestic counter-proliferation and

nuclear/radiological consequence management. The unclassified

nickname for these plans is GRANITE SHADOW.

-

Cover groups - In researching this

story, National Journal identified three Defense Department field

activities whose anodyne names obscure their purpose as accounting

mechanisms for COG funding and operations. The National Security

Staff and the Department of Defense requested that NJ not disclose

the names, locations or functions of these entities.