|

by Zbigniew Brzezinski

Harvard International Review

Winter

1997/1998

From 'The Grand Chessboard - American

Primacy and its Geostrategic Imperatives'

from

HarvardInternationalReview Website

|

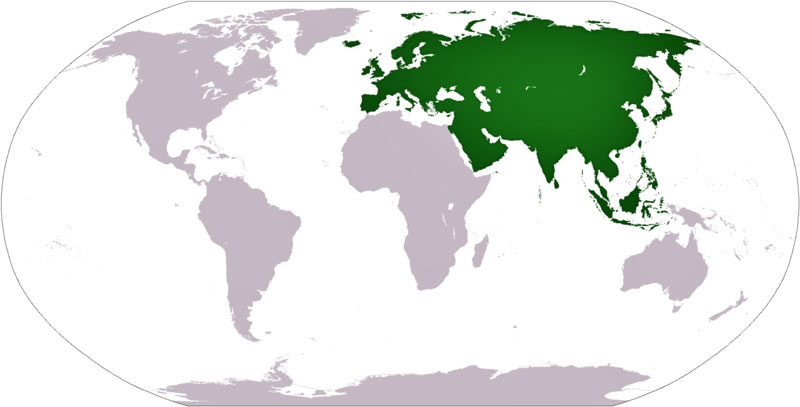

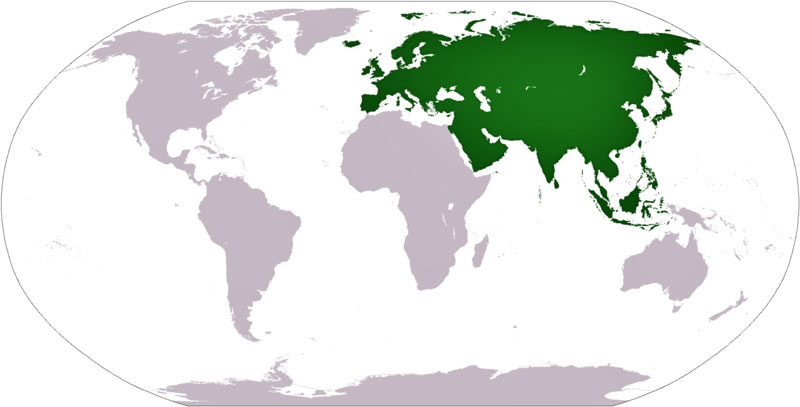

For America, the chief geopolitical

prize is Eurasia. For half a millennium, world affairs were

dominated by Eurasian powers and peoples who fought with one another

for regional domination and reached out for global power. Now a

non-Eurasian power is preeminent in Eurasia—and Americas global

primacy is directly dependent on how long and how effectively its

preponderance on the Eurasian continent is sustained. Obviously,

that condition is temporary.

But its duration, and what follows it, is of critical importance not

only to America's well-being but more generally to international

peace. |

The sudden emergence of the first and only global power has created

a situation in which an equally quick end to its supremacy—either

because of America's withdrawal from the world or because of the

sudden emergence of a successful rival— would produce massive

international instability. In effect, it would prompt global

anarchy.

The Harvard political scientist Samuel P. Huntington is

right in boldly asserting that,

"a world without US primacy will be a

world with more violence and disorder and less democracy and

economic growth than a world where the United States continues to

have more influence than any other country in shaping global

affairs.

The sustained international primacy of the United States is central

to the welfare and security of Americans and to the future of

freedom, democracy, open economies, and international order in the

world."

In that context, how America "manages" Eurasia is critical.

Eurasia

is the globe's largest continent and is geopolitically axial. A

power that dominates Eurasia would control two of the world's three

most advanced and economically productive regions. A mere glance at

the map also suggests that control over Eurasia would almost

automatically entail Africa's subordination, rendering the Western

Hemisphere and Oceania geopolitically peripheral to the world's

central continent.

About 75 percent of the world's people live in

Eurasia, and most of the world's physical wealth is there as well,

both in its enterprises and underneath its soil. Eurasia accounts

for about 60 percent of the world's GNP and about three-fourths of

the world's known energy resources.

Eurasia is also the location of most of the world's politically

assertive and dynamic states. After the United States, the next six

largest economies and the next six biggest spenders on military

weaponry are located in Eurasia. All but one of the world's overt

nuclear powers and all but one of the covert ones are located in

Eurasia. The world's two most populous aspirants to regional

hegemony and global influence are Eurasian.

All of the potential

political and/or economic challengers to American primacy are

Eurasian. Cumulatively, Eurasia's power vastly overshadows

America's. Fortunately for America, Eurasia is too big to be

politically one.

The time has come for the United States to formulate and prosecute

an integrated, comprehensive, and long-term geostrategy for all of

Eurasia. This need arises out of the interaction between two

fundamental realities:

-

America is now the only global superpower

-

Eurasia is the globe's central arena.

US Secretary of

Defense William Cohen and Ukrainian Defense Minister Olexandr Kuzmuk

watch as NATO

exercises promise a secure Europe.

Hence, what happens to the distribution

of power on the Eurasian continent will be of decisive importance to

America's global primacy and to America's historical legacy.

In that context, for some time to come—for more than a generation—

America's status as the world's premier power is unlikely to be

contested by any single challenger. No nation-state is likely to

match America in the four key dimensions of power (military,

economic, technological, and cultural) that cumulatively produce

decisive global political clout. Short of a deliberate or

unintentional American abdication, the only real alternative to

American global leadership in the foreseeable future is

international anarchy. In that respect, it is correct to assert that

America has become, as President Clinton put it, the world's

"indispensable nation."

It is important to stress here both the fact of that

indispensability and the actuality of the potential for global anarchy. The disruptive consequences of population explosion,

poverty-driven migration, radicalizing urbanization, ethnic and

religious hostilities, and the proliferation of weapons of mass

destruction would become unmanageable if the existing and underlying

nation-state-based framework of even rudimentary geopolitical

stability were itself to fragment.

Without sustained and directed

American involvement, before long the forces of global disorder

could come to dominate the world scene. And the possibility of such

a fragmentation is inherent in the geopolitical tensions not only of

today's Eurasia but of the world more generally.

Implications

of European Unity

The United States has always professed its fidelity to the cause of

a united Europe. Ever since the days of the Kennedy administration,

the standard invocation has been that of "equal partnership."

Official Washington has consistently proclaimed its desire to see

Europe emerge as a single entity, powerful enough to share with

America both the responsibilities and the burdens of global

leadership.

That has been the established rhetoric of the subject. But in

practice, the United States has been less clear and less consistent.

Does Washington truly desire a Europe that is a genuinely equal

partner in world affairs, or does it prefer an unequal alliance? For

example, is the United States prepared to share leadership with

Europe in the Middle East, a region not only much closer

geographically to Europe than to America but also one in which

several European states have long-standing interests? The issue of

Israel instantly comes to mind. US-European differences over Iran

and Iraq have also been treated by the United States not as an issue

between equals but as a matter of insubordination.

The emergence of a truly united

Europe—especially if that should occur with constructive American

support—will require significant changes in the structure and

processes of the NATO alliance, the principal link between America

and Europe. NATO provides not only the main mechanism for the

exercise of US influence regarding European matters but the basis

for the politically critical American military presence in Western

Europe.

However, European unity will require that structure to

adjust to the new reality of an alliance based on two more or less

equal partners, instead of an alliance that, to use traditional

terminology, involves essentially a hegemony and its vassals. That

issue has so far been largely skirted, despite the modest steps

taken in 1996 to enhance within NATO the role of the Western

European Union (WEU), the military coalition of the Western European

states. A real choice in favor of a united Europe will thus compel a

far-reaching reordering of NATO, inevitably reducing the American

primacy within the alliance.

In brief, a long-range American geostrategy for Europe will have to

address explicitly the issues of European unity and real partnership

with Europe. An America that truly desires a united and hence also a

more independent Europe will have to throw its weight behind those

European forces that are genuinely committed to Europe's political

and economic integration.

Such a strategy will also mean junking the

last vestiges of the once-hallowed US-UK special relationship.

The NATO Imperative

A policy for a united Europe will also have to address—though

jointly with the Europeans—the highly sensitive issue of Europe's

geographic scope.

The former is more a matter for a

European decision, but a European decision on that issue will have

direct implications for a NATO decision. The latter, however,

engages the United States, and the US voice in NATO is still

decisive.

Given the growing consensus regarding the desirability of

admitting the nations of Central Europe into both the EU and NATO,

the practical meaning of this question focuses attention on the

future status of the Baltic republics and perhaps also that of

Ukraine. There is thus an important overlap between the European

dilemma discussed above and the second one pertaining to Russia. It

is easy to respond to the question regarding Russia's future by

professing a preference for a democratic Russia, closely linked to

Europe.

Presumably, a democratic Russia would be more sympathetic to

the values shared by America and Europe and hence also more likely

to become a junior partner in shaping a more stable and cooperative

Eurasia. But Russia's ambitions may go beyond the attainment of

recognition and respect as a democracy. Within the Russian foreign

policy establishment (composed largely of former Soviet officials),

there still thrives a deeply ingrained desire for a special Eurasian

role, one that would consequently entail the subordination to Moscow

of the newly independent post-Soviet states.

With regard to Russia, the United States faces a dilemma.

-

To what

extent should Russia be helped economically—which inevitably

strengthens Russia politically and militarily—and to what extent

should the newly independent states be simultaneously assisted in

the defense and consolidation of their independence?

-

Can Russia be

both powerful and a democracy at the same time?

-

If it becomes

powerful again, will it not seek to regain its lost imperial domain,

and can it then be both an empire and a democracy?

US policy toward the vital geopolitical pivots of Ukraine and

Azerbaijan cannot skirt that issue, and America thus faces a

difficult dilemma regarding tactical balance and strategic purpose.

Internal Russian recovery is essential to Russia's democratization

and eventual Europeanization. But any recovery of its imperial

potential would be inimical to both of these objectives.

Moreover,

it is over this issue that differences could develop between America

and some European states, especially as the EU and NATO expand.

The costs of the

exclusion of Russia could be high— creating a self-fulfilling

prophecy in the Russian mindset—but the results of dilution of either the EU or NATO could also be quite destabilizing.

Problems at

the Periphery

Another major uncertainty looms in the large and geopolitically

fluid space of Central Eurasia, maximized by the potential

vulnerability of the Turkish-Iranian pivots. In the area from Crimea

in the Black Sea directly eastward along the new southern frontiers

of Russia, all the way to the Chinese province of Xinjiang, then

down to the Indian Ocean and then westward to the Red Sea, then

northward to the eastern Mediterranean Sea and back to Crimea, live

about 400 million people, located in some twenty-five states, almost

all of them

ethnically as well as religiously heterogeneous and practically none

of them politically stable.

Some of these states may be in the

process of acquiring nuclear weapons.

This huge region, torn by volatile hatreds and surrounded by

competing powerful neighbors, is likely to be a major battlefield

both for wars among nation-states and, more likely, for protracted

ethnic and religious violence. Whether India acts as a restraint or

whether it takes advantage of some opportunity to impose its will on

Pakistan will greatly affect the regional scope of the likely

conflicts. The internal strains within Turkey and Iran are likely

not only to get worse but to greatly reduce the stabilizing role

these states are capable of playing within this volcanic region.

Such developments will in turn make it more difficult to assimilate

the new Central Asian states into the international community, while

also adversely affecting the American-dominated security of the

Persian Gulf region. In any case, both America and the international

community may be faced here with a challenge that will dwarf the

recent crisis in the former Yugoslavia.

A possible challenge to American primacy from Islamic fundamentalism

could be part of the problem in this unstable region. By exploiting

religious hostility to the American way of life and taking advantage

of the Arab-Israeli conflict, Islamic fundamentalism could undermine

several pro-Western Middle Eastern governments and eventually

jeopardize American regional interests, especially in the Persian

Gulf.

However, without political cohesion and

in the absence of a single genuinely powerful Islamic state, a

challenge from Islamic fundamentalism would lack a geopolitical core

and would thus be more likely to express itself through diffuse

violence.

A Pragmatic

Approach to China

A geostrategic issue of crucial importance is posed by China's

emergence as a major power. The most appealing outcome would be to

co-opt a democratizing and free-marketing China into a larger Asian

regional framework of cooperation. But suppose China does not

democratize but continues to grow in economic and military power?

A

"Greater China" may be emerging, whatever the desires and

calculations of its neighbors, and any effort to prevent that from

happening could entail an intensifying conflict with China. Such a

conflict could strain American-Japanese relations—for it is far from

certain that Japan would want to follow America's lead in containing

China—and could therefore have potentially revolutionary

consequences for Tokyo's definition of Japan's regional role,

perhaps even resulting in the termination of the American presence

in the Far East.

However, accommodation with China will also exact its own price. To

accept China as a regional power is not a matter of simply endorsing

a mere

slogan. There will have to be substance to any such regional

preeminence.

To put it very directly,

-

How large a Chinese sphere of

influence, and where, should America be prepared to accept as part

of a policy of successfully co-opting China into world affairs?

-

What

areas now outside

of China's political radius might have to be conceded to the realm

of the re-emerging Celestial Empire?

Although China is emerging as a regionally dominant power, it is not

likely to become a global one for a long time to come—and paranoiac

fears of China as a global power are breeding megalomania in China,

while perhaps also becoming the source of a self-fulfilling prophesy

of intensified American-Chinese hostility. Accordingly, China should

be neither contained nor propitiated.

It should be treated with

respect as the world's largest developing state, and— so far at

least —a rather successful one. Its geopolitical role not only in the

Far East but in Eurasia as a whole is likely to grow as well. Hence,

it would make sense to co-opt China into the G-7 annual summit of

the world's leading countries, especially since Russia's inclusion

has widened the summit's focus from economics to politics.

For historic as well as geopolitical reasons, China should consider

America its natural ally. Unlike Japan or Russia, America has never

had any territorial designs on China; and, unlike Great Britain, it

never humiliated China. Moreover, without a viable strategic

consensus with America, China is not likely to be able to keep

attracting the massive foreign investment so necessary to its

economic

growth and thus also to its attainment of regional preeminence. For

the same reason, without an American-Chinese strategic accommodation

as the eastern anchor of America's involvement in Eurasia, America

will not have a geostrategy for mainland Asia; and without a

geostrategy for mainland

Asia, America will not have a geostrategy for Eurasia. Thus for

America, China's regional power, co-opted into a wider framework of

international cooperation, can be a vitally important geostrategic

asset— in that regard coequally important with Europe and more

weighty than Japan in assuring Eurasia's stability.

Emerging

Challenges

In the past, international affairs were largely dominated by

contests among individual states for regional domination.

Henceforth, the United States may have to determine how to cope with

regional coalitions that seek to push America out of Eurasia,

thereby threatening America's status as a global power. However,

whether any such coalitions do or do not arise to challenge American

primacy will in fact depend to a very large degree on how

effectively the United States responds to the major dilemmas

identified here.

Potentially, the most dangerous scenario would be a grand coalition

of China, Russia, and perhaps Iran, an "antihegemonic" coalition

united not by ideology but by complementary grievances. It would be

reminiscent in scale and scope of the challenge once posed by the

Sino-Soviet bloc, though this time China would likely be the leader

and Russia the follower. Averting this contingency, however remote

it may be, will require a display of US geostrategic skill on the

western, eastern, and southern perimeters of Eurasia simultaneously.

A geographically more limited but potentially even more

consequential challenge could involve a Sino-Japanese axis, in the

wake of a collapse of the American position in the Far East and a

revolutionary change in Japan's world outlook. It would combine the

power of two extraordinarily productive peoples, and it could

exploit some form of "Asianism" as a unifying anti-American

doctrine. However, it does not appear likely that in the foreseeable

future China and Japan will form an alliance, given their recent

historical experience; and a farsighted American policy in the Far

East should certainly be able to prevent this eventuality from

occurring.

Also quite remote, but not to be entirely excluded, is the

possibility of a grand European realignment, involving either a

German-Russian collusion or a Franco-Russian entente. There are

obvious historical precedents for both, and either could emerge if

European unification were to grind to a halt and if relations

between Europe and America were to deteriorate gravely. Indeed, in

the latter eventuality, one could imagine a European-Russian

accommodation to exclude America from the continent. At this stage,

all of these variants seem improbable. They would require not only a

massive mishandling by America of its European policy but also a

dramatic reorientation on the part of the key European states.

Whatever the future, it is reasonable to conclude that American

primacy on the Eurasian continent will be buffeted by turbulence and

perhaps at least by sporadic violence. America's primacy is

potentially vulnerable to new challenges, either from regional

contenders or novel constellations.

The currently dominant American

global system, within which "the threat of war is off the table," is

likely to be stable only in those parts of the world in which

American primacy, guided by a long-term geostrategy, rests on

compatible and congenial sociopolitical systems, linked together

by American-dominated multilateral frameworks.

A Geostrategy

For Eurasia

The point of departure for the needed policy has to be hard-nosed

recognition of the three unprecedented conditions that currently

define the geopolitical state of world affairs: for the first time

in history,

-

a single state is a truly global power

-

a

non-Eurasian state is globally the preeminent state

-

the

globe's central arena, Eurasia, is dominated by a non-Eurasian

power

However, a comprehensive and integrated

geostrategy for Eurasia must

also be based on recognition of the limits of America's effective

power and the inevitable attrition over time of its scope. The very

scale and diversity of Eurasia, as well as the potential power of

some of its states, limit the depth of American influence and the

degree of control over the course of events.

This condition places a

premium on geostrategic insight and on the deliberately selective

deployment of America's resources on the huge Eurasian chessboard.

And since America's unprecedented power is bound to diminish over

time, the priority must be to manage the rise of other regional

powers in ways that do not threaten America's global primacy.

Eurasia

In the short run, it is in America's interest to consolidate and

perpetuate the prevailing geopolitical pluralism on the map of

Eurasia. That puts a premium on maneuver and manipulation in order

to prevent the emergence of a hostile coalition that could

eventually seek to challenge America's primacy, not to mention the

remote possibility of any one particular state seeking to do so.

By

the middle term, the foregoing should gradually yield to a greater

emphasis on the emergence of increasingly important but

strategically compatible partners who, prompted by American

leadership, might help to shape a more cooperative trans-Eurasian

security system. Eventually, in the much longer run still, the

foregoing could phase into a global core of genuinely shared

political responsibility.

The most immediate task is to make certain that no state or

combination of states gains the capacity to expel the United States

from Eurasia or even to diminish significantly its decisive

arbitrating role. However, the consolidation of transcontinental

geopolitical pluralism should not be viewed as an end in itself but

only as a means to achieve the middle-term goal of shaping genuine

strategic partnerships in the key regions of Eurasia.

It is unlikely

that democratic America will wish to be permanently engaged in the

difficult, absorbing, and costly task of managing Eurasia by

constant manipulation and maneuver, backed by American military

resources, in order to prevent regional domination by any one power.

The first phase must, therefore, logically and deliberately lead into the second, one in which a benign American

hegemony still discourages others from posing a challenge not only

by making the costs of the challenge too high but also by not

threatening the vital interests of Eurasia's potential regional

aspirants.

What that requires specifically, as the middle-term goal, is the

fostering of genuine partnerships, predominant among them those with

a more united and politically defined Europe and with a regionally

preeminent China, as well as with (one hopes) a post-imperial and

Europe-oriented Russia and, on the southern fringe of Eurasia, with

a regionally stabilizing and democratic India. But it will be the

success or failure of the effort to forge broader strategic

relationships with

Europe and China, respectively, that will shape the defining context

for Russia's role, either positive or negative.

It follows that a wider Europe and an enlarged NATO will serve well

both the short-term and the longer-term goals of US policy. A larger

Europe will expand the range of American influence—and, through the

admission of new Central European members, also increase in the

European councils the number of states with a pro-American

proclivity—without simultaneously creating a Europe politically so

integrated that it could soon challenge the United States on

geopolitical matters of high importance to America elsewhere,

particularly in the Middle East. A politically defined Europe is

also essential to the progressive assimilation of Russia into a

system of global cooperation.

Meeting these challenges is America's burden as well as its unique

responsibility. Given the reality of American democracy, an

effective response will require generating a public understanding of

the continuing importance of American power in shaping a widening

framework of stable geopolitical cooperation, one that

simultaneously averts global anarchy and successfully defers the

emergence of a new power challenge.

These two goals—averting global

anarchy and impeding the emergence of a power rival—are inseparable

from the longer-range definition of the purpose of America's global

engagement, namely, that of forging an enduring framework of global

geopolitical cooperation.

In brief, the US policy goal must be unapologetically twofold:

-

to

perpetuate America's own dominant position for at least a generation

and preferably longer still

-

to create a geopolitical framework

that can absorb the inevitable shocks and strains of

social-political change while evolving into the geopolitical core of

shared responsibility for peaceful global management

A prolonged

phase of gradually expanding cooperation with key Eurasian partners,

both stimulated and arbitrated by America, can also help to foster

the preconditions for an eventual upgrading of the existing and

increasingly antiquated UN structures. A new distribution of

responsibilities and privileges can then take into account the

changed realities of global power, so drastically different from

those of 1945.

These efforts will have the added historical advantage of benefiting

from the new web of global linkages that is growing exponentially

outside the more traditional nation-state system.

That web, woven by:

-

multinational corporations

-

NGOs (non-governmental organizations,

with many of them transnational in character)

-

scientific

communities

-

reinforced by the Internet

...already creates an

informal global system that is inherently congenial to more

institutionalized and inclusive global cooperation.

In the course of the next several decades, a functioning structure

of global cooperation, based on geopolitical realities, could thus

emerge and gradually assume the mantle of the world's current

"regent," which has for the time being assumed the burden of

responsibility for world stability and peace.

Geostrategic success

in that cause would represent a fitting legacy of America's role as

the first, only, and last truly global superpower.

|