by Wayne Madsen

04 March, 2011

from

Opinion-Maker Website

For some three decades, local residents near a

top secret terrorist training base have reported on hearing explosions,

seeing sudden flashes of light and night time flares, and noticing small

planes and "black helicopters" arriving at and departing from a small

airfield on the base.

The airspace over the base is off-limits to

unauthorized aircraft.

The base is not in Pakistan's restive Waziristan region or in Lebanon's

Bekaa Valley but in northeastern North Carolina on Albemarle Sound, near the

town of Hertford. Officially known as the Harvey Point Defense Testing

Activity base, which was once a Navy Supply Center, it actually serves

as a paramilitary training course for the CIA and allied intelligence and

paramilitary services, including Israel's Mossad and Britain's Special Air

Services (SAS).

On March 20, 1998, The New York Times reported

that during its existence, Harvey Point trained 18,000 foreign intelligence

operatives from 50 different countries.

Among those terrorists trained at Harvey Point were those who worked for,

-

the Chilean military junta of General

Augusto Pinochet

-

El Salvador's death squad chief Roberto

D'Aubisson

-

Egypt's General Intelligence Directorate

-

Katangan secessionist leader Moise

Tshombe

-

Angola's UNITA guerrilla force

-

Colombian counter-insurgency personnel

-

Laotian anti-communist paramilitary

forces

-

Arab cadres who would later join Osama

bin Laden's forces fighting against the Soviets in Afghanistan

One can only contemplate how such regulars and

irregulars from the far-flung corners of the world reacted to eastern North

Carolina cuisine, including the barbecued pork, hush puppies, and steamed

crabs.

First used to train anti-Castro Cubans for the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1960,

the base has seen Lebanese Phalangist militia train for the failed March 8,

1985, west Beirut car bombing assassination attempt against Lebanese Shi'a

spiritual leader Muhammad Hussein Fadlallah, who was also known to be

a leading figure in Hezbollah.

Although Fadlallah escaped assassination, the

car packed with 440 pounds of dynamite leveled an apartment building and a

movie theater, killing 80 innocent people, including women and children, and

injuring some 300 others.

As the United Nations Special Tribunal for Lebanon stands ready to indict

key members of Lebanese Hezbollah for the February 15, 2005, massive car

bombing that took the life of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri,

it is noteworthy that it has been the CIA, along with its Lebanese allies

and Mossad agents trained at Harvey Point who have specialized in the urban

car bombing tactic used so often over the past several decades in Lebanon.

And as WMR previously reported, it was these

same elements - CIA, Mossad, and their Lebanese assets - that jointly

carried out the Hariri car bombing assassination.

An article titled "CIA Missions Have Mysterious N.C. Roots" in the June 28,

1978, The Virginian-Pilot and The Ledger-Star, a newspaper in

Norfolk, Va., publishes the most detailed article to date about the CIA and

Harvey Point, described as an annex of the CIA training base at Camp Peary,

Virginia, was being used to train CIA operatives in car bombings.

The paper noted that every few days, Navy trucks

hauled batches of new passenger vehicles into the base and every few days

cars that were totally demolished were trucked out of the base.

Some local residents described the vehicles:

some had their hoods blown off while others

were smashed flat.

In December 1999, a rumbling from the base,

which lasted for up to five seconds, was so strong that thousands of people

in the region believed it to be an earthquake. The US Geological Survey said

it did not register any quakes in the region.

In 2009, the CIA conducted a security survey of the Elizabeth City water

plant and found that security controls were lacking. The CIA pressed local

officials to beef up security for the plant.

Former CIA operative Robert Baer wrote in his book, "See

No Evil," that his two weeks of training at

Point Harvey

was, for all purposes,

an "advanced terrorism course."

Baer was trained in the use of plastic and other

types of explosive materials.

It is believed that former CIA and Chilean DINA

intelligence agent Michael Townley, convicted in 1978 for the 1976

car bombing assassination in Washington, DC of former Chilean Foreign

Minister Orlando Letelier and his American assistant, Roni Moffitt.

Townley became part of the federal witness

protection program in 1978 after his conviction in the murder of Letelier.

However, Townley was spotted in Stockholm in 1986 a week before the

assassination of Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme.

After 9/11, CIA paramilitary operatives who were assigned to the agency's

Special Activities Division (SAD) and deployed against the Taliban in

Afghanistan were first trained at Harvey Point.

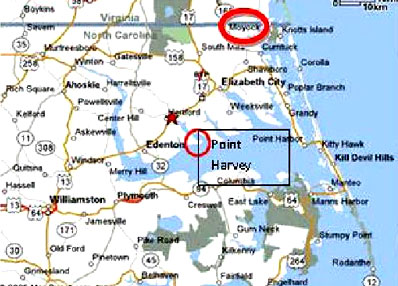

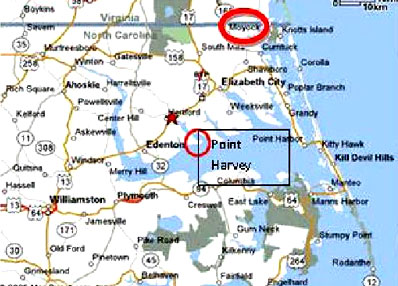

Northeast North Carolina

Center of global terrorist

training activity and home to CIA's Harvey Point car bombing training

facility

and Xe (former

Blackwater) false flag terror camp.

With the current controversy raging about the

roles that acting CIA station chief in Pakistan Raymond Davis and

suspected CIA agent Aaron DeHaven, both jailed in Pakistan - Davis

for murder of two Pakistani nationals and DeHaven for visa violations - may

have played in false flag terrorist attacks in Pakistan, there is an

interesting footnote to Harvey Point.

Just north of the CIA terrorist training

facility, past Elizabeth City, lies the sprawling Moyock, North

Carolina training facility of the company formerly called

Blackwater and now known as Xe Services.

Now known as the

United States Training Center, the

Moyock facility is on a former U.S. Navy installation that once hosted a

U.S. Naval Security Group Activity listening station that was part of the

National Security Agency's global signals intelligence eavesdropping

network.

Harvey Point is used by Navy SEALS/Underwater Demolition Teams for training.

Blackwater founder Erik Prince had served

as a Navy SEAL and many of his early Blackwater employees were ex-SEALS.

Their numbers were later supplemented by retired CIA officers.

Navy SEALS/UDT and CIA teams trained at Harvey

Point in the 1980s for the illegal planting of mines in Nicaraguan waters.

In 1990, personnel trained at the base unsuccessfully attempted to capture

Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar in the secret "POKEWEED" operation.

In 2008, the U.S. government used an eminent domain acquisition to procure

the Moorman Pine tract adjacent to Harvey Point for use by the CIA base. The

owners of the tract acquired the property in 2002 for a golf and residential

project. The owners settled with the government for $5.8 million.

The operations of Harvey Point and Moyock appear to complement one another

and jointly place a huge secretive CIA footprint in northeast North

Carolina.

The Truth About Harvey Point

by Jon Elliston

June 05, 2002

from

IndyWeek Website

Facts about the CIA's activities at Harvey Point, along with other details

about the secretive facility, have seeped out slowly over the years. Pieces

of the puzzle have surfaced in government documents, investigative news

reports and accounts by former CIA officers.

Below is a chronological summary of previous

disclosures about the base.

-

1961: The U.S. Navy announces in June

that it will establish a secret weapons testing facility at Harvey

Point. A spokesman says that some of the training currently

conducted at Camp Perry in Virginia will be moved here. (Camp Perry

is later identified as the CIA's main officer training school.)

-

1967: The magazine Ramparts, in the

midst of a series of exposÚs on the CIA's domestic operations,

publishes a detailed testimonial by an anonymous former CIA officer.

He writes that he decided to quit the agency because of what he was

taught at "demolition training headquarters." He does not, however,

name the location of the base.

-

1974: In their groundbreaking

intelligence history, The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence, former

CIA officer Victor Marchetti and former State Department officer

John Marks note that "demolitions and heavy weapons" are "taught at

a secret CIA base in North Carolina."

-

1975: The President's Commission on CIA

Activities within the United States offers the first official

disclosure about Harvey Point in its final report. The report

reveals only a portion of the CIA's activities, however, saying

merely that the agency has used the facility for training domestic

and foreign policy forces in bomb detection and disposal.

-

1976: "Purported CIA Base Classified,

Fenced," says the headline of an article in the Burlington Daily

Times-News, which reports mounting speculation about the agency's

activities at Harvey Point.

-

1978: Outside magazine reveals that the

CIA trained amateur mountain climbers at Harvey Point in the early

1960s. The climbers were ultimately sent into a remote region of

India on a failed mission to place a listening station that would

monitor Chinese nuclear tests.

Shortly thereafter, The Virginian-Pilot and The Ledger-Star, a

newspaper in Norfolk, Va., publishes the most detailed article to

date about the CIA and Harvey Point. Titled "CIA Missions Have

Mysterious N.C. Roots," the article reveals that the facility has

been instrumental in training U.S. and foreign operatives for some

of the agency's most sensitive projects.

-

1985: The Washington Post reveals that

the CIA has trained a force of Lebanese operatives to rescue U.S.

hostages and stage paramilitary attacks. The group winds up killing

80 civilians in a failed assassination attempt. Leaders of the group

received CIA training in North Carolina, writer Amir Taheri reveals

in his 1988 book, Nest of Spies.

-

1998: The New York Times reports that

the CIA recently trained security forces from the Palestinian

Authority at Harvey Point.

-

1999: Jane's Intelligence Review, a

respected journal based in London, publishes a detailed report on

the CIA's commando units, revealing additional details about the

training at Harvey Point.

-

Nov. 2001: Washington Post reporter Bob

Woodward reports that CIA paramilitary operatives are leading the

way in the war against the Taliban. A follow-up report in the London

newspaper the Guardian notes that the operatives trained at Harvey

Point.

-

Jan. 2002: In his book

See No Evil, which is vetted by the

CIA prior to publication, former CIA officer Bob Baer describes his

two weeks at Harvey Point. "By the end of the training, we could

have taught an advanced terrorism course," he writes.

Bomb School

by Jon Elliston

June 05, 2002

from

IndiWeek Website

recovered through

WayBackMachine Website

|

After 41 years of explosive training at

a secret base in eastern North Carolina, the CIA's paramilitary wing

is back on the front lines.

For the base's neighbors in nearby

Hertford, the echo of bombs is business as usual - and nobody's

business. |

On April 11, 2002, Jim Pavitts, the Central Intelligence Agency's top

covert operations official, stood up before a Duke University Law School

conference on national security issues and did something he almost never

does: He spoke publicly about his operations. In the little-noticed speech,

Pavitts assured the audience that the CIA is actively engaged in the fight

against terrorism.

To prove it, he cited the early involvement of

the agency's commandos in Operation Enduring Freedom.

"Teams of my paramilitary operations

officers, trained not just to observe conditions but if need be to

change them, were among the first on the ground in Afghanistan," Pavitts

said.

Indeed, the first U.S. casualty, Johnny "Mike"

Spann, who was killed in the prison uprising at Mazar-e-Sharif on Nov. 25,

was one of those officers.

Spann was part of an elite and super-secretive

unit, the CIA's Special Activities Division, which serves as the knifepoint

of the agency's cloak and dagger contributions to national security.

With personnel drawn from other commando units

like the Navy SEALs and the Army Special Forces, the unit is skilled in the

dark arts of paramilitary warfare:

assassination, advanced demolitions,

high-tech surveillance and behind-enemy-lines combat.

"In those few days that it took us to get

there after that terrible, terrible attack" on Sept. 11, Pavitts

continued, "my officers stood on Afghan soil, side by side with Afghan

friends that we had developed over a long period of time, and we

launched America's war against al-Qaeda."

Pavitts offered few details, saying he could share "just a bit" of what the

CIA has been up to lately.

Among the matters he did not discuss was North

Carolina's crucial but behind-the-scenes role in the CIA's paramilitary

program.

Officials have maintained strict silence about that role for more than four

decades. In fact, no serving CIA officer has ever uttered the words "Harvey

Point" in public.

That's because the Harvey Point Defense Testing

Activity, a high-security compound tucked into a quiet corner of marshland

near Hertford, N.C., and officially owned by the Defense Department, has

served as the spy agency's secret demolitions training base since 1961.

It's where CIA operatives like the ones who

infiltrated Afghanistan - and the ones who will likely lead the way in the

next battles of the war against terrorism, starting with Iraq - learn the

rough stuff.

The CIA's covert warriors train as secretly as they spy and fight. So at

Harvey Point, the boom! boom! is very hush-hush.

It's late one Friday afternoon in May, and downtown Hertford is basking in

75-degree sunlight and coastal breezes carrying the smell of barbecue. The

town is staging its annual "Pig Out on the Green." After paying $5 a plate,

a hundred or so citizens are chowing down over checkered tablecloths in

front of the Perquimans County Courthouse.

A local cover band plays light Southern rock

from the front of the building, which is flanked by two monuments: one to

the area's Confederate Civil War dead, the other to Hertford's most famous

native son, baseball great Jim "Catfish" Hunter.

Hertford Mayor Sid Eley, who also serves as director of the

Perquimans County Chamber of Commerce, is wearing a floppy fishing hat and

manning a giant barbecue bucket.

He ladles out hearty servings of pork while

other town workers pile on potatoes and coleslaw.

"When you're done with that, make sure you

head across the street to Woodmere's Pharmacy for some of that good ice

cream," he says as he passes a plate.

Hertford, the population of which has remained

steady at about 2,000 for the last 50 years, is surrounded by marshy inlets

and sparsely populated farms where corn, cotton and soybeans are grown.

Looking up and down the stretch of Church Street

where the courthouse sits, there are roughly 20 businesses, and just one,

the corner Amoco, is a chain store. Only the modern offices of a local

Internet service provider seem out of place.

On this lazy afternoon, it's a postcard-perfect scene from small-town

America. But Mayor Eley, like most other locals, knows that this is no

ordinary backwater community. Beneath the quiet veneer lies an explosive

secret: The citizens of Hertford live a few miles up the road from a

classified facility that exists to help the government break things and kill

people - and do so in secret.

Unlike most locals, Eley has actually been there. A few years ago, the

director of the base at Harvey Point, which is fenced in and doesn't allow

in visitors, invited a group of about 25 local officials to come have a look

around.

During the unprecedented visit, Eley was told that the base is used by all

branches of the armed services, along with other federal entities, for

testing explosives.

"They took us out there and showed us

basically what they do," Eley remembers.

"We were in a bunker and they gave us a

display. They started with a hand-grenade - I had never seen an actual

hand-grenade go off. Then they worked their way up to bigger stuff and

eventually they blew up a car. The top of it flew way back over our

heads."

Such tests, Eley was told, are intended to help

the authorities detect and contain terrorist bombs.

For instance, Harvey Point personnel said they

had staged re-enactments of the bombing that took place at the 1996 Summer

Olympics in Atlanta, trying to determine precisely what sort of device had

been used.

After a short briefing, a lengthy bombing display and a good meal at the

base cafeteria, the visit was over.

Grateful for the peek inside the secret

facility, some of the civic officials sent a thank-you note to Harvey

Point's director:

"When we hear an explosion from that general

direction or feel the ground shake due to the same, we will, from our

experience, know, in some degree, what it is for. We will now be able to

explain to our people why we have the Base and what it is doing for our

Nation."

But those explanations are still necessarily

incomplete, because, as Eley and other local leaders readily admit, they

still don't know the details about who trains at Harvey Point, and to what

ends.

And most of the base's neighbors, it seems, are content not to know.

"This CIA crap, it's all just speculation,"

says Charles Skinner, a retiree who serves as the town's resident local

historian, about the widely reported accounts concerning the base.

"I don't know what they're doing. They might

be playing with Roman candles down there. It's very obviously

explosives, because you can feel the vibrations. But I'm not that

concerned, so I don't pay any attention to it, no more than thunder."

"Everybody's just satisfied that we're up

here and they're down there," says Susan R. Harris, editor and publisher

of the Perquimans Weekly, explaining why her newspaper rarely reports on

the base.

For anyone who does want to know, getting the

facts from the government can prove to be a frustrating endeavor.

Because of the shroud of secrecy over Harvey

Point, military and intelligence spokespeople have difficulty being candid

about it, and they can't quite get the cover story straight. The Independent

started by calling the Navy, which acquired the property during World War II

and later announced it was setting up an off-limits testing center there.

A spokesman for the Navy's Mid-Atlantic Region

Command in Norfolk, Va., which oversees operations in the area, checked with

the Defense Department and then referred questions to the CIA.

A CIA public affairs officer, in turn, refused

to discuss the base and suggested contacting the Defense Department.

Eventually, a Pentagon spokesman, Maj. Mike Halbig, agreed to field

questions about Harvey Point.

"The Department of Defense took over the

facility in 1961," he says. "The primary mission is to test and evaluate

conventional explosives, ordnance and ballistic materials."

And what of the stories that it's a major center

for CIA special warfare training?

"It is a Department of Defense facility that

serves the military services and it serves the special needs of other

U.S. government departments," is all Halbig will say. Base personnel

cannot speak to reporters, he says, nor can visits be arranged.

"The projects and materials that they test

there are highly classified, and for that reason we do not allow public

access," he says.

It's true that the CIA hasn't been the only

government entity to make use of Harvey Point.

According to press reports and government

documents, over the years, several military units and police squads have

trained there, along with personnel from the DEA, FBI, Secret Service and

other agencies. A recent Treasury Department report, for example, says that

the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy and the Defense

Department have established a joint program at Harvey Point for devising

methods of stopping drug runners.

Despite the CIA's best efforts to keep its role at Harvey Point under wraps,

there is a mounting body of public information about the base's secret

history. The latest example.

In his newly published memoir,

See No Evil: The True Story of a Ground Soldier in the

CIA's War on Terrorism, former CIA officer Bob Baer

describes the "two weeks of nonstop demolition training" he received in

North Carolina as a young recruit in the early 1970s:

"We spent two days crimping blasting caps to

make sure we understood that if you crimped them too high, they'd

explode and take your hand off. After we'd mastered that, we crimped

them in the dark, by feel.

Then we started blowing things up: cars,

buses, diesel generators, fences, bunkers. We made a school bus

disappear with about 20 pounds of U.S. C-4. For comparison's sake, we

tried Czech Semtex and a few other foreign plastic explosives.

"Not that you really needed anything fancy. We blew up one bus using

three sacks of fertilizer and fuel oil, a mixture called ANFO (ammonium

nitrate fuel oil), that did more damage than the C-4 had. The biggest

piece left was a part of the chassis, which flew in an arc, hundreds of

yards away.

We learned to mix up a potent cocktail

called methyl nitrate. If you hit a small drop of it with a hammer, it

split the hammer. Honest. We were also taught some of the really

esoteric stuff like E-cell times, improvising pressurized airplane bombs

using a condom and aluminum foil, and smuggling a pistol on an airplane

concealed in a mixture of epoxy and graphite.

By the end of the training, we could have

taught an advanced terrorism course."

Long before the CIA arrived to practice blowing

things up, Harvey Point was a storied and mysterious place.

A small peninsula that pokes into the north side

of the Albemarle Sound, in the early 1700s it served as the stomping ground

of the infamous pirate Blackbeard. Around the same time, North Carolina's

first native-born governor, Thomas Harvey, lived here, as did his grandson,

John Harvey, one of the key local leaders to conspire against English

authorities and launch the Revolutionary War.

Several members of the Harvey family are buried at Harvey Point. But the

public can't visit the historic gravesite, which features some of the oldest

known tombstones in North Carolina. Today those stones sit within the

classified confines of Harvey Point.

The Navy bought the 1,200-acre peninsula in November 1942, paying five

land-owners a total of $41,751 for the property and quickly setting up an

air station to help fight World War II. After the war, the site served as a

blimp base, but remained relatively quiet until another big project came

along.

In 1958, the Navy chose Harvey Point to house an experimental long-range

bomber, the "Martin P6M Seamaster."

The size of a B-52, the plane took off from and

landed in the waters near Harvey Point, but as a viable weapon, it never

really got off the ground. It crashed and burned too often for the Navy to

sustain the project, and just one year later, in August 1959, the fleet of

six Seamasters was mothballed.

The closing of the base hit Hertford hard. Local merchants were counting on

revenues from Naval aviators and their support staff. Charles Skinner

remembers one businessman, in particular, who was devastated.

The man had opened The Seamaster Tavern, a

short-lived beer garden.

"When they pulled out the seaplane, he had

to close up," Skinner says.

Rep. Herbert Bonner, a Democrat who then

represented the area in Congress, met with the Secretary of the Navy and

pleaded that a new use for the facility be found.

Shortly thereafter, his request was granted, and

this time, Harvey Point would be getting a lot more than a half-dozen sea

planes: The CIA was about to open an outpost in North Carolina.

The agency has never disclosed its reasons for setting up an undercover bomb

school at Harvey Point. But the timing and the context, along with scattered

press reports, offer indications of the base's original purpose. Fidel

Castro, it seems, was the impetus - and the target of the first commandos to

train at Harvey Point.

The story begins in 1959, when Castro led a revolutionary government to

power in Cuba. At first, White House officials hoped to topple him quickly.

In March of 1960, President Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered the CIA to create a

force of anti-Castro, Cuban exile fighters, and John F. Kennedy, who

succeeded Eisenhower in 1961, authorized the operation to go forward.

In mid-April of that year, the CIA staged its most ambitious and disastrous

paramilitary operation: the Bay of Pigs invasion. It took Castro's military

and militia just three days to rout the agency's force of 1,300 Cuban

exiles. The debacle was viewed as an abject failure by the CIA's

paramilitary wing.

Harvey Point had played a supporting role in the disaster, press reports

would later reveal. The CIA quietly amassed weapons for the operation at the

base, which was secretly on its way to becoming a full-blown training

facility.

In June of 1961, two months after the Bay of Pigs invasion, the Navy

announced it was officially opening a new facility at the old Seamaster

base. A spokesman said that all four branches of the military would conduct

"testing and evaluation of various classified materials and equipment" at

the site.

He added that training,

"now being done at Camp Perry, Va., will be

transferred to Harvey Point."

At the time, Camp Perry, which is located next

to Williamsburg, was officially a military base.

But since then, reporters and CIA veterans have

written about the camp's true role: It is the agency's training compound for

new spy officers. Code-named ISOLATION, the 12,000-acre Camp Perry is

referred to in the intelligence community as "the Farm," and to this day it

serves as the CIA's main spy school. But in 1961, the agency moved its most

dangerous and sensitive training - in demolitions and unconventional

weaponry - to Harvey Point.

Following the Bay of Pigs, Harvey Point is one place where the CIA hoped to

continue efforts to undermine Castro.

JFK wanted the job done right, and he appointed

his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, to oversee the new

operations, which mainly consisted of hit-and-run sabotage raids.

"Bobby wanted boom and bang all over the

island," Sam Halpern, a high-ranking officer on the CIA's Cuba desk,

told a historian years later.

The "boom and bang" the Kennedy brothers pressed

for would be taught at Harvey Point.

The base was code-named ISOLATION TROPIC, but

most of the operatives who trained there came to call it "the Point." Over

the years, it has carved out a unique space in paramilitary history as a

clandestine landmark, of sorts. Veterans who have passed through it share an

intimate knowledge of how covert action plays a central role in U.S. foreign

policy.

Over the years, U.S. and foreign commandos who

trained at "the Point" have fought in shadowy conflicts around the globe,

from Cuba to the Congo, from Nicaragua to Vietnam, and lately, in

Afghanistan.

For its first decade or so of operations, the base managed to maintain the

covert character the CIA was looking for. But slowly, parts of the real

story began to filter out. (See "The

Truth About Harvey Point")

A major, but still only partial, disclosure

appeared in the April 1967 edition of Ramparts, a once popular and now

defunct leftist magazine. The issue carried a testimonial from a CIA officer

who had recently resigned after passing through the agency's demolitions

course.

The former officer, who kept his name out of print, did not specify the

location of his training.

But now it's clear that the place he wrote

about, the place where he ultimately soured on the CIA, was Harvey Point:

"The stated purpose of the paramilitary

school was to train and equip us to become instructors for village

peasants who wanted to defend themselves against guerrillas. I could

believe in that.

"Some of the training was conventional: But then we moved to the CIA's

demolition training headquarters. It was here that Cubans had been, and

still were, being trained in conventional and underwater demolitions.

And it was here that we received training in tactics which hardly

conform to the Geneva Convention.

"The array of outlawed weaponry with which we were familiarized included

bullets that explode on impact, silencer-equipped machine guns,

home-made explosives and self-made napalm for stickier and hotter

Molotov cocktails. We were taught demolition techniques, practicing on

late-model cars, railroad trucks, and gas storage tanks. And we were

shown a quick method for saturating a confined area with flour or

fertilizer, causing an explosion like in a dustbin or granary.

"And then there was a diabolical invention that might be called a

mini-cannon. It was constructed of a concave piece of steel fitted into

the top of a #10 can filled with a plastic explosive. When the device

was detonated, the tremendous heat of friction of the steel turning

inside out made the steel piece a white-hot projectile.

There were a number of uses for the

mini-cannon, one of which was demonstrated to us using an old Army

school bus. It was fastened to the gasoline tank in such a fashion that

the incendiary projectile would rupture the tank and fling flaming

gasoline the length of the bus interior, incinerating anyone inside.

It was my lot to show the rest of the class

how easily it could be done. I stood there watching the flames consume

the bus. It was, I guess, the moment of truth. What did a busload of

burning people have to do with freedom? What right did I have, in the

name of democracy and the CIA, to decide that random victims should die?

The intellectual game was over. I had to

leave."

Of course most officers stayed in the spy

agency, and the operations that benefited from such training were many and

varied.

In 1978, Outside magazine published a detailed

account of a madcap mission involving Harvey Point. According to the

magazine, in 1964, the CIA brought a small group of amateur mountain

climbers to the base for demolitions training. The climbers later

infiltrated an isolated mountain range in India in an attempt to place

listening devices for monitoring Chinese nuclear tests.

The mission failed, but at Harvey Point, the

climbers did learn how to blow a hole in a glacier where the devices were

supposed to be placed.

Those who trained at Harvey Point certainly learned how to do some damage,

and some continued to use their deadly skills after they quit working for

the CIA. The Cuban exiles were perhaps the most prodigious bomb experts to

pass through the facility. Not only did they set off a sizable wave of

terrorism against Cuba, some of them went freelance after their CIA ties

were cut, and helped make Miami the car-bomb capital of the world during the

1970s.

In addition, Cuban exile operatives, some of

whom had received CIA training, staged two audacious acts of terrorism in

1976: They bombed a Cuban airliner, killing 73 people, and participated in

the assassination of Chilean exile leader Orlando Letelier and his

assistant, Ronni Moffitt, who were killed by a car bomb as they drove up

Embassy Row in Washington, D.C.

In the 1980s, Harvey Point played a role in some of the CIA's most

controversial covert operations. In 1983, a team of agency operatives mined

Nicaraguan harbors - while floating the cover story that Nicaraguan contra

guerrillas had placed the mines. The attack prompted quick rebukes from

Congress, which moved to halt funding of such sabotage operations.

According to a 1999 article in Jane's

Intelligence Weekly, which detailed the CIA's modern paramilitary

capabilities, the team that mined the harbors trained at Harvey Point.

About the same time, the agency used the base to train three Lebanese

operatives for a most-sensitive mission:

They would lead a special, CIA-sponsored

squad for rescuing U.S. hostages and combating Islamic extremists.

The operation is detailed in two books,

In March 1985, the squad staged a disastrous

assassination attempt against a prominent holy warrior in Beirut.

They missed their target, but managed to kill an

estimated 80 civilians when their car bomb crashed into the wrong building.

As a result, the CIA cut its ties to the group.

Even then, the CIA continued to instruct foreign operatives, along with its

own personnel, in North Carolina. In 1998, The New York Times reported that

Harvey Point's most recent guests included members of the security detail

for Yasser Arafat's Palestinian Authority.

Today, Harvey Point may be playing its most important role ever.

The CIA's Special Activities Division - its

paramilitary force - did indeed lead the way in Afghanistan, according to a

recent report in the Boston Globe. The article, citing officials in the

White House and CIA, revealed that an agency force of 50 paramilitary

officers infiltrated Afghanistan on Sept. 27, 2001. Another 100 followed

soon thereafter.

Inside Taliban territory, the operatives, working in small teams, spread out

and laid the groundwork for the coming combat.

They passed cash to Northern Alliance leaders

and earned their allegiance. They acquired safe houses and conducted

surveillance for the Army's Special Forces, which would be soon arriving by

the hundreds to do the bulk of the fighting. Later, the CIA's commandos

identified targets for the agency's pilot-less Predator drones, which fired

down laser-targeted missiles on al-Qaeda leaders.

Such operations were the opening salvo in the war against terrorism, and a

sign that the CIA is in the midst of its biggest expansion of paramilitary

operations since the Reagan era, according to press reports and intelligence

experts. In February, the Associated Press reported the basic details of the

Bush administration's funding request for the CIA during the next fiscal

year.

The agency's overall budget will increase from

roughly $3.5 billion to almost $5 billion.

A good portion of that spending will be focused on bulking up the CIA's

commando force, says John Pike, director of

Global Security.org, a defense and

intelligence policy research group in Washington, D.C.

"Most of it will have to be going toward

counterterrorism, toward the kinds of things they do at Harvey Point

more than the kinds of things they do at Camp Perry," where traditional

espionage is taught. The CIA, he says, is "hiring a lot of muscle."

The

Bush administration's plans to continue a global war against

terrorism could portend still more CIA paramilitary operations, Pike says.

The next target is Iraq, and if some Bush

advisors get their way, the agency will lead the way in an attempt to

overthrow Saddam Hussein. One faction within the administration is reported

to be arguing that "the Afghanistan scenario" - carefully crafted covert

operations, along with airstrikes and coordinated attacks by opposition

groups - could do the job, sparing the United States from a major military

commitment.

Another faction argues that Hussein is too entrenched to be toppled as

easily as was the Taliban.

Pike agrees.

"I don't think the CIA can get rid of Saddam

Hussein," he says. "The joke going around is that this is the 'Bay of

Goats' plan - it's probably just enough to get a lot of people killed

and not enough to remove Hussein."

But both President Bush and CIA Director

George Tenet are fans of the CIA's paramilitary performance in

Afghanistan, according to recent press reports, and both may soon order

similar operations in Iraq, if they haven't already.

Whatever covert operations are in the works, the secretive yet noisy

training at Harvey Point continues. In Hertford, the echo of bombs is

business as usual - and nobody's business.

Despite all the intrigue emanating from their

community, most people living near Harvey Point have gotten used to the boom

and bang.

"They're good neighbors," says a woman

standing in the doorway of her home on Harvey Point Road. "They don't

bother us and we don't bother them."

The woman, who has shared a property line with

the base for 20 years, asks that her name not be printed and says she's not

precisely sure what goes on behind the facility's fenced perimeter.

"It's for testing explosives, and that's all

I know," she says. "A lot of different looking things go by here," she

adds, pointing to the road that runs past her house to Harvey Point's

high-security gateway.

"Like busses that you can't see through the

windows of, and a lot of old cars and trucks that they blow up. When you

see an 18-wheeler going in at midnight, you wonder what they're carrying

in there."

The noise isn't usually a bother, but,

"every once in a blue moon, they let off a

good one," she says. "When they do one of the big ones, it jars

everything, shakes everything for a few seconds."

Several times a month, the sound of the bomb

blasts is strong enough to carry two miles to the east, to Holiday Island, a

spot popular with boaters that cruise the waters off of Harvey Point.

April Ghose, 17, has lived there for nine years.

"I heard it was FBI or CIA training, one of

them," she says. "When I first moved down here, I didn't know what it

was. My house started trembling and I said, 'Granma, what was that?' And

she was like, 'It's just Harvey Point.' Now it's not a really big deal,

I'm so used to it."

But Ghose's great-grandmother, she says, can't

get used to it:

"She just turned 87. She has really bad

Alzheimer's, so when it comes she doesn't know what's happening."

Phillip Jackson, a 15-year-old friend of Ghose's

who lives in Hertford, says that the main thing he knows about Harvey Point

is that he's not supposed to go anywhere near it.

"My stepdad, he's heard of people going down

there too close in boats, and looking in there with binoculars, and they

get shot," Jackson says. "The law around here is, if you get a hundred

feet from the fence they can shoot you."

Other locals say there have been no such

shootings, but that boaters who stray too close are told to back off by

Harvey Point security guards.

In fact, most of the community's experience with Harvey Point has been good,

according to Perquimans County Manager Paul Gregory Jr.

"I'm not aware of any danger in the past or

in the present," he says, and besides, the base is at least a small

economic boon.

Twenty or so local civilians, he estimates, work

at the base as mechanics, janitors and cafeteria staff.

"For us, that's a lot of jobs, anytime you

get over 10 or 15 jobs. That's a big positive for Perquimans County."

Gregory goes so far as to say that,

"we've not had any negative impacts

whatsoever from them being there."

But local officials have no oversight authority

for Harvey Point, because it is a federal facility.

"They've provided good jobs, but they

haven't provided a whole lot of information about what they say and do

in there," he says.

County officials do not know, for example, what

environmental damage, if any, has resulted from four decades of bomb

testing.

The base at Harvey Point does have a full-time

environmental coordinator, Dr. Wade Jordan, but when The Independent

contacted him recently on the telephone, he said he is not permitted to talk

to the press.

Publicly available federal records do indicate that an environmental cleanup

company, Potomac-Hudson Engineering Inc., did work at Harvey Point in 1996.

According to a company-written summary of the

job, the Defense Department paid $250,000 for,

"remediation of PCB and VOC contaminated

soils at explosives test range and waste asbestos."

Gregory says that the county has a more pressing

concern than Harvey Point - another national security project that could

potentially disrupt the good life in Hertford.

The Navy is seeking landing sites for a new

fleet of F/A-18 "Super Hornets," an exceedingly noisy jet that will be based

in Norfolk, Va.

A spot five miles north of Hertford is on the

Navy's short list, and in response, Perquimans officials have joined several

neighboring counties to lobby against locating an airstrip in their neck of

the woods.

"We are patriotic, but we've got

agriculture, we've got tourism and we're a popular place for retirement

- that's all we've got going for us," Gregory says. "If the noise comes,

there goes the tourism, there go the retirees, who aren't going to want

to live here."

The Navy is slated to name its Super Hornet

landing sites later this year.

Whatever happens with the Navy's jets, it seems like the CIA's bomb school

is here to stay. Last year's defense appropriations bill authorized the Navy

to purchase an additional 200 acres in Perquimans County,

"To provide a buffer zone for the Harvey

Point Defense Testing Activity."

And if the Bush administration decides to try

the "Afghanistan scenario" in Iraq - using the CIA's troops as a vanguard -

then the tempo of the training may well increase.

Bob and Thelma Brannock, two retired postal workers who live across the

Perquimans River from Harvey Point, say they're content to let the

government's secret warriors do their thing - whatever it is. Through the

windows in their living room, they can see the mini marina the CIA built

around the concrete ramps that the Navy Seamaster planes once used to get to

their hangars. They can see the mouth of the clearing that leads to the

base's airstrip.

Since nothing but a few acres of trees surrounding the base and a

mile-and-half of open water stand between their house and Harvey Point, the

Brannocks don't just have the best view - they also hear the bombs more than

most folks do.

The loudest blasts,

"sound like the fireworks on the fourth of

July," according to Bob.

"Sometimes I actually thought they were

right here in the yard," Thelma says. "But it hasn't done any damage to

our house. Now I have heard some people say it knocks the pictures off

the wall."

"It doesn't bother us," Thelma says as Bob nods.

"I know roughly what it is, and to me, we

need some security someplace. Everybody shouldn't know everything, as

long as they're protecting us. We can't know everything or else all the

other countries will know everything. It kind of makes me mad when I

hear people say they don't want it around, because the noise bothers

them. They've got to train somewhere."

Bob thinks for a minute, then says cryptically:

"I think you don't wanna know. My theory is

that there's a lot going on over there."

Additional Information