by Eric Lichtblau

November 13, 2010

from

NYTines Website

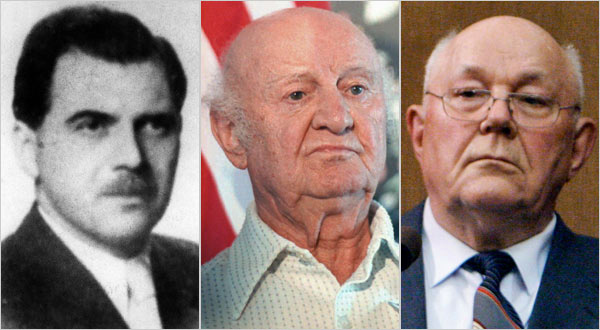

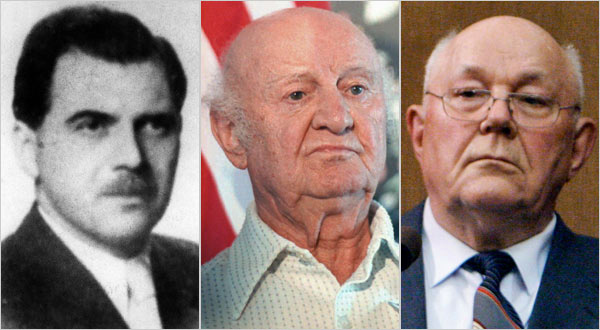

Dr. Josef Mengele in

1956, left.

Arthur Rudolph, center, in

1990, was a rocket scientist for Nazi Germany and NASA.

John Demjanjuk, right, in

2006

WASHINGTON

A secret history of the United States

government’s Nazi-hunting operation concludes that American intelligence

officials created a “safe haven” in the United States for Nazis and their

collaborators after World War II, and it details decades of clashes, often

hidden, with other nations over war criminals here and abroad.

The 600-page report,

which the Justice Department has tried to keep secret for four years,

provides new evidence about more than two dozen of the most notorious Nazi

cases of the last three decades.

It describes the government’s posthumous pursuit of Dr. Josef Mengele,

the so-called Angel of Death at Auschwitz, part of whose scalp was

kept in a Justice Department official’s drawer; the vigilante killing of a

former Waffen SS soldier in New Jersey; and the government’s mistaken

identification of the Treblinka concentration camp guard known as Ivan the

Terrible.

The report catalogs both the successes and failures of the band of lawyers,

historians and investigators at the

Justice Department’s Office of Special

Investigations, which was created in 1979 to deport Nazis.

Perhaps the report’s most damning disclosures come in assessing the

Central

Intelligence Agency’s involvement with

Nazi émigrés.

Scholars and previous government reports had

acknowledged the

C.I.A.’s use of Nazis for postwar intelligence purposes.

But this report goes further in documenting the level of American complicity

and deception in such operations.

The Justice Department report, describing what it calls,

“the government’s collaboration with

persecutors,” says that O.S.I investigators learned that some of the

Nazis “were indeed knowingly granted entry” to the United States, even

though government officials were aware of their pasts.

“America, which prided itself on being a

safe haven for the persecuted, became - in some small measure - a safe

haven for persecutors as well,” it said.

The report also documents divisions within the

government over the effort and the legal pitfalls in relying on testimony

from Holocaust survivors that was decades old.

The report also concluded that the number of

Nazis who made it into the United States was almost certainly much smaller

than 10,000, the figure widely cited by government officials.

The Justice Department has resisted making the report public since 2006.

Under the threat of a lawsuit, it turned over a

heavily redacted version

last month to a private research group, the National Security Archive, but

even then many of the most legally and diplomatically sensitive portions

were omitted.

A complete version

was obtained by The New York Times.

The Justice Department said the report, the product of six years of work,

was never formally completed and did not represent its official findings. It

cited “numerous factual errors and omissions,” but declined to say what they

were.

More than 300 Nazi persecutors have been deported, stripped of citizenship

or blocked from entering the United States since the creation of

the O.S.I.,

which was

merged with another unit this year.

In chronicling the cases of Nazis who were aided by American intelligence

officials, the report cites help that C.I.A. officials provided in 1954 to

Otto Von Bolschwing, an associate of Adolf Eichmann who had

helped develop the initial plans “to purge Germany of the Jews” and who

later worked for the C.I.A. in the United States.

In a chain of memos, C.I.A. officials debated

what to do if Von Bolschwing were confronted about his past - whether to

deny any Nazi affiliation or,

“explain it away on the basis of extenuating

circumstances,” the report said.

The Justice Department, after learning of Von

Bolschwing’s Nazi ties, sought to deport him in 1981. He died that year at

age 72.

The report also examines the case of Arthur L. Rudolph, a Nazi

scientist who ran the Mittelwerk munitions factory. He was brought to the

United States in 1945 for his rocket-making expertise under

Operation Paperclip, an American program that recruited

scientists who had worked in Nazi Germany. (Rudolph has been honored by NASA

and is credited as the father of the Saturn V rocket.)

The report cites a 1949 memo from the Justice Department’s No. 2 official

urging immigration officers to let Rudolph back in the country after a stay

in Mexico, saying that a failure to do so “would be to the detriment of the

national interest.”

Justice Department investigators later found evidence that Rudolph was much

more actively involved in

exploiting slave laborers at Mittelwerk than he or

American intelligence officials had acknowledged, the report says.

Some intelligence officials objected when the Justice Department sought to

deport him in 1983, but the O.S.I. considered the deportation of someone of

Rudolph’s prominence as an affirmation of “the depth of the government’s

commitment to the Nazi prosecution program,” according to internal memos.

The Justice Department itself sometimes concealed what American officials

knew about Nazis in this country, the report found.

In 1980, prosecutors filed a motion that “misstated the facts” in asserting

that checks of C.I.A. and F.B.I. records revealed no information on the Nazi

past of Tscherim Soobzokov, a former Waffen SS soldier.

In fact, the report said, the Justice

Department,

“knew that Soobzokov had advised the C.I.A.

of his SS connection after he arrived in the United States.”

(After the case was dismissed, radical Jewish

groups urged violence against Mr. Soobzokov, and he was

killed in 1985 by a

bomb at his home in Paterson, N.J.)

The secrecy surrounding the Justice Department’s handling of the report

could pose a political dilemma for President

Obama

because of his pledge to run the most 'transparent' administration in

history. Mr. Obama chose the Justice Department to coordinate the

opening of government records.

The Nazi-hunting report was the brainchild of Mark Richard, a senior

Justice Department lawyer. In 1999, he persuaded Attorney General Janet Reno

to begin a detailed look at what he saw as a critical piece of history, and

he assigned a career prosecutor, Judith Feigin, to the job.

After Mr. Richard edited the final version in

2006, he urged senior officials to make it public but was rebuffed,

colleagues said.

When Mr. Richard became ill with cancer, he told a gathering of friends and

family that the report’s publication was one of three things he hoped to see

before he died, the colleagues said.

He died in June 2009, and Attorney General

Eric

H. Holder Jr. spoke at his funeral.

“I spoke to him the week before he died, and

he was still trying to get it released,” Ms. Feigin said. “It broke his

heart.”

After Mr. Richard’s death, David Sobel, a

Washington lawyer, and the National Security Archive sued for the report’s

release under the Freedom of Information Act.

The Justice Department initially fought the lawsuit, but finally gave Mr.

Sobel a partial copy - with more than 1,000 passages and references deleted

based on exemptions for privacy and internal deliberations.

Laura Sweeney, a Justice Department spokeswoman, said the department

is committed to transparency, and that redactions are made by experienced

lawyers.

The full report disclosed that the Justice Department found “a smoking gun”

in 1997 establishing with “definitive proof” that Switzerland had bought

gold from the Nazis that had been taken from Jewish victims of the

Holocaust. But these references are deleted, as are disputes between the

Justice and State Departments over Switzerland’s culpability in the months

leading up to a major report on the issue.

Another section describes as “a hideous failure” a series of meetings in

2000 that United States officials held with Latvian officials to pressure

them to pursue suspected Nazis. That passage is also deleted.

So too are references to macabre but little-known bits of history, including

how a director of the O.S.I. kept a piece of scalp that was thought to

belong to Dr. Mengele in his desk in hopes that it would help establish

whether he was dead.

The chapter on Dr. Mengele, one of the most notorious Nazis to escape

prosecution, details the O.S.I.’s elaborate efforts in the mid-1980s to

determine whether he had fled to the United States and might still be alive.

It describes how investigators used letters and diaries apparently written

by Dr. Mengele in the 1970s, along with German dental records and Munich

phone books, to follow his trail.

After the development of DNA tests, the piece of scalp, which had been

turned over by the Brazilian authorities, proved to be a

critical piece of

evidence in establishing that Dr. Mengele had fled to Brazil and had died

there in about 1979 without ever entering the United States, the report

said. The edited report deletes references to Dr. Mengele’s scalp on privacy

grounds.

Even documents that have long been available to the public are omitted,

including court decisions, Congressional testimony and front-page newspaper

articles from the 1970s.

A chapter on the O.S.I.’s most publicized failure - the case against

John

Demjanjuk, a retired American autoworker who was mistakenly identified

as Treblinka’s Ivan the Terrible - deletes dozens of details,

including part of a 1993 ruling by the United States Court of Appeals for

the Sixth Circuit that raised ethics accusations against Justice Department

officials.

That section also omits a passage disclosing that Latvian émigrés

sympathetic to Mr. Demjanjuk secretly arranged for the O.S.I.’s trash to be

delivered to them each day from 1985 to 1987.

The émigrés rifled through the garbage to find

classified documents that could help Mr. Demjanjuk, who is currently

standing trial in Munich on separate war crimes charges.

Ms. Feigin said she was baffled by the Justice Department’s attempt to keep

a central part of its history secret for so long.

“It’s an amazing story,” she said, “that

needs to be told.”