|

from BusinessInsider Website

In an interview with Business Insider following the launch of his latest book "The Euro - How A Common Currency Threatens the Future of Europe" - which argues that the European single currency will inevitably cease to be at some point in the future unless drastic changes are made - Stiglitz said that a "disastrous" political event similar to the United Kingdom's decision to leave the European Union could trigger such a collapse.

Stiglitz continued:

Asked if he believed that the ongoing problems - both politically and economically - in Italy could trigger such an event, Stiglitz agreed, saying:

Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi has a lot on his plate. REUTERS/Max Rossi

Renzi has frequently reiterated that he will step down as prime minister if he loses the referendum, in a move that would mimic British PM David Cameron's resignation following the EU referendum in June.

As it stands, Stiglitz argued, the referendum is,

Although Renzi is adamant that he and his government will succeed in their aim of reforming Italy's senate, saying in a recent interview "I will win" - Stiglitz believes that the best option for the future stability of Europe would be for the referendum to be abandoned.

Despite Stiglitz's assertion that the referendum should not go ahead, it seems unlikely that it would be cancelled with just a couple of months until it is due to take part.

The vote has now been formally approved by the Italian high court, and is set to take place on an as yet undetermined date in November this year. In the run-up to the UK's vote to leave the European Union, Italy's litany of problems had gone largely unnoticed.

However, in recent months, the spotlight has turned toward the southern European state, the Eurozone's third largest economy. Italy not only faces political turmoil but enormous economic strife too.

It has crushingly low productivity, a history of missing growth targets, and has generally underperformed the rest of Europe in recent years.

Earlier in August, economic data out of the country showed that GDP did not grow in the second quarter of 2016, a substantially worse outcome than economists very modest expectations of 0.2% growth.

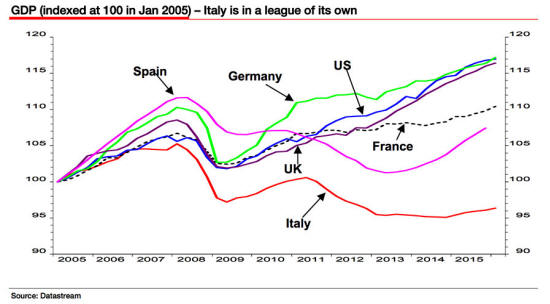

Here is just one chart showing how drastic things are when it comes to the Italian economy compared to other major economies (you can find more here):

Societe Generale

Not only is Italy in the midst of major political and economic drama, it is also staring down a huge crisis in its financial system.

The country's financial sector is plagued by an enormous surfeit of bad loans so great that the government was, in April, forced into rallying bank executives, insurers and investors to put €5 billion (£4.2 billion, $5.57 billion) behind a rescue fund for its weakest banks.

The

Atalante fund is designed to buy so-called bad loans from lenders

and invest in their shares in the hope that the re-energized banks

will lend more to businesses and spur growth. Monte dei Paschi di Siena, the world's oldest bank, is the worst affected, holding bad loans equivalent to almost 50 times its market capitalization.

The bank managed to agree a rescue package involving the likes of,

...at the end of July.

Monte dei Paschi's shares have lost more than 99% of their value in less than 10 years. Bank of America Merrill Lynch

However, soon afterwards the lender came dead last in the European Banking Association's continent-wide stress tests, and in the last week, it has been revealed that the company's CEO Fabrizio Viola is under investigation for alleged market manipulation.

The problems in Italy's banking system, Stiglitz argues, are endemic of the unnecessary rigidity within the Eurozone's rules.

Whatever the "cataclysm" that leads to the eventual collapse of the euro and the European project, right now, it looks like Italy is the most probable culprit.

You can read the first part of Business Insider's interview with Stiglitz, in which he discusses the "death" of the neoliberal economic consensus, here below:

'Neoliberalism is Dead'

Getty/Win

McNamee

Speaking with Business Insider after the launch of his latest book, "The Euro - How a Common Currency Threatens the Future of Europe" - which argues that the fundamental flaws with the euro and the broader European economy are causing huge problems for the continent and risk leading to its downfall - Stiglitz argued that neoliberalism, the dominant school of economic thinking in the West for the past 30 years or so, is on its last legs.

Since the late 1980s and the so-called Washington Consensus, neoliberalism - essentially the idea that,

...are the best ways to boost growth - has dominated the thinking of the world's biggest economies and international organizations like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

The policies of Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton in the US and Margaret Thatcher in the UK are often held up as the gold standard of neoliberalism at work, while in recent years in Britain George Osborne and David Cameron's economic policies continued the neoliberal tradition.

Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, neoliberalism's two greatest champions. REUTERS/Larry Rubenstein

Since the 2008 financial crisis, however, there has been a groundswell of opinion in both economic and political circles to suggest that the neoliberal consensus may not be the right way forward for the world. In the past few years, with growth low and inequality rampant, that groundswell has gained traction.

Stiglitz, who won a Nobel Memorial Prize in economics in 2001 for his work on information asymmetry, has been one of neoliberalism's biggest critics in recent years, and he says the "neoliberal euphoria" that has gripped the world since the 1980s is now gone.

Asked by Business Insider whether he thought the economic consensus surrounding neoliberalism was coming to an end, Stiglitz argued:

Stiglitz went on to argue that one of the central tenets of the neoliberal ideology - the idea that markets function best when left alone and that an unregulated market is the best way to increase economic growth - has now been pretty much disproved.

In other words, Stiglitz says:

Stiglitz is not alone in his belief that neoliberalism has its problems, though his argument that the consensus is "dead" is somewhat more forthright than those of many others.

In a blog post in May, three economists from the IMF - long one of the greatest champions of the neoliberal consensus - questioned the efficacy of some aspects of it, particularly when it comes to the creation of inequality.

Joseph Stiglitz with Christine Lagarde, the International Monetary Fund managing director. Lagarde is not one of those within the IMF questioning neoliberalism. Reuters/Philippe Wojaze

The decline of neoliberalism

The decline of neoliberalism is also evident in the UK, where austerity has reigned since the accession of the Conservative Party to government in 2010.

Prime Minister David Cameron and Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne presided over a period of record fiscal-deficit reduction created through a six-year programme of austerity.

But since Cameron resigned following the UK's vote to leave the European Union, fiscal stimulus in the UK has started to gain traction once again as a viable means of stimulating growth.

It is widely expected that Philip Hammond, the new chancellor under newly installed Prime Minister Theresa May, will announce some form of fiscal easing at the Autumn Statement - which will come at some point before the end of the year (last year's was in late November).

As Business Insider's Oscar Williams-Grut argued in mid-July,

Across the Atlantic, both US presidential nominees, Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, both favoring expanded government borrowing to fund infrastructure projects.

As Randall W. Forsyth argued in Barron's magazine last week:

Neoliberalism may not be completely dead, as Stiglitz argues, but it is certainly being challenged from many angles.

|