|

by Dr. Douglas Kriner

and Dr. Francis Shen

June 19,

2017

from

SSRN Website

|

Douglas Kriner is a

professor of political science at Boston University. His

research interests include American political

institutions, separation of powers dynamics, and

American military policymaking. Professor Kriner

graduated Phi Beta Kappa from MIT in 2001 and received

his Ph.D. in Government from Harvard University in 2006.

He has recently published two books on inter-branch

politics. The first, with Andrew Reeves, The

Particularistic President: Executive Branch Politics and

Political Inequality (Cambridge 2015; winner of the 2016

Richard E. Neustadt Award), explores how electoral,

partisan, and coalitional incentives compel presidents

to target federal resources disproportionately toward

some parts of the country and away from others. The

second, with Eric Schickler, Investigating the

President: Congressional Checks on Presidential Power

(Princeton 2016), examines Congress' ability to retain

some check on the aggrandizement of presidential power

through the investigatory arm of its committees. He is

also the author of After the Rubicon: Congress,

Presidents, and the Politics of Waging War (Chicago

2010; winner of the 2013 D.B. Hardeman Award) and

co-author, with Francis Shen, of The Casualty Gap: The

Causes and Consequences of American Military

Policymaking (Oxford 2010). Professor Kriner's work has

also appeared in the American Political Science Review,

American Journal of Political Science, and Journal of

Politics, among other outlets.

Francis Shen is an Associate Professor of Law at the

University of Minnesota, where he directs the Shen

Neurolaw Lab and explores the intersection of

neuroscience and law. He is also an Affiliated Faculty

Member at the Center for Law, Brain, and Behavior at

Massachusetts General Hospital, and serves as Executive

Director of Education and Outreach for the MacArthur

Foundation Research Network on Law and Neuroscience. Dr.

Shen received his B.A. from the University of Chicago,

his J.D. from Harvard Law School, and his Ph.D. in

Government and Social Policy from Harvard University. He

has co-authored 3 books, including The Casualty Gap: The

Causes and Consequences of American Wartime Inequalities

(Oxford 2010), co-authored with Professor Douglas Kriner.

Kriner and Dr. Shen have also authored a number of

articles on American combat casualties, including most

recently Invisible Inequality: The Two Americas of

Military Sacrifice (2016). In addition to combat

casualties research, Dr. Shen has also published

articles on a range of neurolaw topics, including

criminal law, tort law, mental health, legislation,

dementia, and evidence. |

Abstract

America has been at war continuously for over 15 years, but few

Americans seem to notice.

This is because the vast majority of

citizens have no direct connection to those soldiers fighting,

dying, and returning wounded from combat. Increasingly, a divide is

emerging between communities whose young people are dying to defend

the country, and those communities whose young people are not.

In

this paper we empirically explore whether this divide - the casualty

gap - contributed to

Donald Trump's surprise victory in November 2016.

The data analysis presented in this working paper finds that indeed,

in the 2016 election Trump was speaking to this forgotten part of

America. Even controlling in a statistical model for many other

alternative explanations, we find that there is a significant and

meaningful relationship between a community's rate of military

sacrifice and its support for Trump.

Our statistical model suggests

that if three states key to Trump's victory - Pennsylvania,

Michigan, and Wisconsin - had suffered even a modestly lower

casualty rate, all three could have flipped from red to blue and

sent Hillary Clinton to the White House.

There are many implications

of our findings, but none as important as what this means for

Trump's foreign policy. If Trump wants to win again in 2020, his

electoral fate may well rest on the administration's approach to the

human costs of war.

Trump should remain highly sensitive to American combat casualties,

lest he become yet another politician who overlooks the invisible

inequality of military sacrifice.

More broadly, the findings suggest

that politicians from both parties would do well to more directly

recognize and address the needs of those communities whose young

women and men are making the ultimate sacrifice for the country.

Battlefield

Casualties and Ballot Box Defeat: Did the Bush-Obama Wars Cost

Clinton the White House?

I -

Introduction

Imagine a country continuously at war for nearly two decades.

Imagine that the wars were supported by both Democratic and

Republican presidents.

Continue to imagine that the country fighting these wars relied only

on a small group of citizens - a group so small that those who served

in theater constituted less than 1 percent of the nation's

population, while those who died or were wounded in battle comprised

far less than 1/10th of 1 percent of the nation's population. 1

And

finally, imagine that these soldiers, their families, friends, and

neighbors felt that their sacrifice and needs had long been ignored

by politicians in Washington.

Would voters in these hard hit communities get angry? And would they

seize an opportunity to express that anger at both political

parties? We think the answer is yes. And the proof is the 2016

victory of Donald J. Trump.

Trump's victory over Hillary Clinton has prompted massive

speculation about how the political pundits got it wrong. 2 Some

suggest it was Hillary's poor strategy and lack of messaging, 3 while

others point to Trump's ability to connect emotionally with an angry

electorate. 4

Still others emphasize macro-level forces like the

economy. 5

With so much post-election analysis, it is surprising that no one

has pointed to the possibility that inequalities in wartime

sacrifice might have tipped the election. Put simply: perhaps the

small slice of America that is fighting and dying for the nation's

security is tired of its political leaders ignoring this

disproportionate burden. 6

To investigate this possibility, we

conducted an analysis of the 2016 Presidential election returns. In

previous research, we've shown that communities with higher casualty

rates are also communities from more rural, less wealthy, and less

educated parts of the country. 7

In both 2004 and 2006,

voters in these communities became more likely to vote against

politicians perceived as orchestrating the conflicts in which their

friends and neighbors died. 8

The data analysis presented in this working paper finds that in the

2016 election Trump spoke to this part of America. Even controlling

in a statistical model for many other alternative explanations, we

find that there is a significant and meaningful relationship between

a community's rate of military sacrifice and its support for Trump.

Indeed, our results suggest that if three states key to Trump's

victory - Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin - had suffered even a

modestly lower casualty rate, all three could have flipped from red

to blue and sent Hillary Clinton to the White House.

There are many implications of our findings. First, the findings

should signal to the White House that Trump's 2020 electoral fate

may well rest on the administration's approach to the human costs of

war.

If Trump wants to maintain his connection to this part of his

base, his foreign policy would do well to be highly sensitive to

American combat casualties.

Many politicians have exhibited casualty sensitivity of course, but

if this segment of the electorate is particularly important to

Trump's fortunes in 2020, it may suggest a more powerful democratic

brake on foreign wars.

Second, the findings are also a lesson for

the Democrats and establishment Republicans who are still trying to

figure out how to beat Trump.

Our analysis suggests that politicians

from both parties would do well to more directly recognize and

address the needs of those communities whose young women and men are

making the ultimate sacrifice for the country.

Third, the results

also raise puzzling questions about the relationship between some of

Trump's rhetoric (for instance his highly-publicized argument with a

Gold Star family) and his perception amongst communities with higher

casualty rates. Further research is required to explore these and

other implications.

The paper proceeds as follows.

In Part II, we review the relevant

scholarly literature on the political costs of high casualty rates.

In Part III, we present our analysis of the relationship between

local casualty rates and support for Trump.

In Part IV, we begin to

explore the implications of these results for policymaking and

campaign strategy.

II - Donald

Trump and the Politics of War Casualties

Between October 10, 2001 and the 2016 presidential election, almost

7,000 American service members lost their lives in wars in

Afghanistan and Iraq.

While the American public

initially rallied in support of both conflicts, public support

soured as their human costs rose. 9

Despite the kindling of

an Iraqi insurgency and President

Bush's embarrassingly premature

declaration of "Mission Accomplished," Bush secured reelection in

2004. However, he lost significant electoral ground in states and

communities that had paid the heaviest share of the war burden in

casualties. 10

By 2006, the continuing deterioration of the situation

in Iraq emboldened Democrats to promise to end the war in the Middle

East. That year's midterm elections returned Democrats to power in

both chambers of Congress for the first time since before the 1994

Republican Revolution. Underlying this sweeping change was a further

erosion in support for the GOP among the constituencies hardest hit

by the war.

In both the Senate 11 and the House,

12 Republican losses

were steepest among communities that had suffered disproportionately

high casualty rates in Iraq. 13

Finally, in the 2008 presidential

election one of the starkest points of contrast between

Barack Obama

and John McCain was their diametrically opposite views on the Iraq

War. McCain was a steadfast supporter and argued that the U.S. must

assiduously stay the course to ultimate victory. Obama had opposed

the war from the start and promised to end the conflict.

Voters

ultimately chose Obama in a landslide.

The electoral punishment suffered by Republicans in the 2000s was a

story of both casualty and economic inequality. The communities

suffering the most from the fighting overseas were communities with

lower income and education levels. 14

These communities, in turn, increasingly turned

against political candidates insisting on more combat.

The resulting

GOP losses in communities hardest hit by the war echoes findings

from previous conflicts. When the United States goes to war, the

sacrifice that war exacts in blood is far from uniformly distributed

across the country. 15 And in the Civil War, 16 Korea,

17 Vietnam, 18

and Iraq, 19 constituencies that have suffered the highest casualty

rates have proven most likely to punish the ruling party at the

polls.

While previous research tells us much about how incumbent

politicians lose votes due to battlefield casualties, it offers few

clues as to how a candidate might win back such voters.

In many respects, the bombastic campaign of the billionaire

businessman and political neophyte Donald Trump appeared consciously

calculated to appeal to communities fed up with fifteen years of

costly and inconclusive war.

The core of Trump's nationalist,

populist message was to "make America great again." While the

details of the message shifted as the campaign developed, Trump

regularly praised the military - while also noting that at least some

of their efforts seemed to have been for naught.

On the campaign trail, Trump sometimes sounded like a traditional

hawk. He repeatedly mocked the Obama administration's passive

approach toward the Islamic State and boasted of

his intention to "bomb the hell out of ISIS."

Similarly, he derided

the Iran nuclear pact as one of the "worst deals" ever and promised

a more aggressive posture with increasingly bellicose rhetoric.

Channeling his inner Reagan, Trump also called for greater military

spending across the board, including on nuclear weapons, even if

such moves threatened to trigger a new arms race.

And perhaps above

all, Trump regularly pledged in his stump speeches to take care of

the military. 20 He noted repeatedly that the military's resources,

especially its manpower resources, were "depleted." 21

A Trump

administration, he promised, would bring fresh manpower and weapons.

However, other Trump campaign themes were decidedly iconoclastic.

While few Republicans openly lauded the Iraq War in 2016, Trump

vehemently denounced it and the Republican president who waged it.

22

In a nationally televised debate before the South Carolina

primary, Trump minced few words:

"I want to tell you. They lied.

They said there were weapons of mass destruction, there were none.

And they knew there were none." 23

Again and again on the campaign

trail, Trump labeled Iraq a disaster and pledged to keep the United

States out of stupid wars.

As an example of this approach, when

asked how to grapple with the quagmire in Syria, Trump sang the

virtues of allowing Russia to play the lead role, as it would keep

the United States out of another costly and unnecessary foreign war.

24

This

theme was consistent with a similar sentiment from his kick-off

speech, where he both criticized the war in Iraq and recognized the

sacrifice of American troops:

"We spent $2 trillion in Iraq, $2

trillion. We lost thousands of lives, thousands in Iraq. We have

wounded soldiers, who I love, I love - they're great - all over

the place, thousands and thousands of wounded soldiers." 25

In sum, Trump promised a foreign policy that would be both

simultaneously more muscular and more restrained.

Trump promised to

rebuild and refocus the military:

"Our active duty armed forces have

shrunk from 2 million in 1991 to about 1.3 million today. … Our

military is depleted, and we're asking our generals and military

leaders to worry about global warming."

And he also promised to be

much more reticent in its use:

"Our friends and enemies must know

that if I draw a line in the sand, I will enforce it. However,

unlike other candidates for the presidency, war and aggression will

not be my first instinct.

You cannot have a foreign policy without

diplomacy. A superpower understands that caution and restraint are

signs of strength." 26

III - Assessing

Trump's Electoral Performance in High Casualty Constituencies

In one sense, all Americans have been affected by fifteen years of

nearly continuous war in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Americans of all

stripes have watched each conflict's developments unfold through

extensive media coverage, movies, and personal stories from veterans

returning from combat.

Indeed, so great are its posited effects on

American society that some analysts have proclaimed the emergence of

an "Iraq Syndrome," echoing the public skepticism about the efficacy

of the use of force and the growing popular reluctance to employ it

that emerged after Vietnam. 27

However, on another, very

tangible dimension, some Americans have experienced the costs of war

much more acutely than others.

Most directly, of course, the costs

of war have been concentrated on those men and women who fought and

died in foreign theaters and on their families.

But Americans'

exposure to these costs has also varied significantly according to

the experience of their local communities. In the Iraq and

Afghanistan wars, for example, seven states have suffered casualty

rates of thirty or more deaths per million residents. By contrast,

four states have suffered casualty rates of fifteen or fewer deaths

per million.

As a result, Americans living in these states have had

different exposure to the war's human costs through the experiences

of their friends and neighbors and local media coverage. 28

At lower levels of aggregation, the disparities are often even more

extreme.

For example,

as of the 2016

election, just over 50% of U.S. counties had experienced a

casualty rate in Iraq and Afghanistan of 1 or fewer deaths per

100,000 residents.

However, more than a quarter of counties had

experienced a casualty rate more than 3.5 times greater, and 10%

of counties had suffered casualty rates of more than 7 deaths

per 100,000 residents.

Voters in such communities increasingly

abandoned Republican candidates in a series of elections in the

2000s. 29

To examine whether the

Trump campaign was able to reverse the GOP's earlier losses among

those constituencies hardest hit by the nation's recent wars, we

conduct analyses at both the state and county level.

Following

previous research on the electoral impact of local casualties,

30 we operationalize the dependent variable as the change in the two

party-vote share received by the Republican candidate from 2012 to

2016.

This allows us to examine where Trump out-performed Mitt Romney four

years prior. Moreover, using the change in vote share from one

election to the next provides an important measure of statistical

control as many factors that affect the GOP vote share in a

constituency should have remained roughly unchanged over this short

four-year period.

To measure variation in communities' exposure to wartime casualties,

we accessed data from the Defense Casualty Analysis System of the

Department of Defense on 6,856 American soldiers killed pursuant to

operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. 31

Of these service members,

6,732 listed home of record information from one of the 50 states,

and 10 hailed from the District of Columbia. From this data, we

constructed casualty counts for each state and divided them by state

population to construct a casualty rate per million residents.

32

For

the vast majority of these soldiers, the DoD also provided a home

county of record. 33 To capture the greater nuance in the uneven

geographic allocation of casualties across the country, we

constructed casualty counts for each county and then divided them by

each county's population to create a casualty rate per 10,000

residents. 34

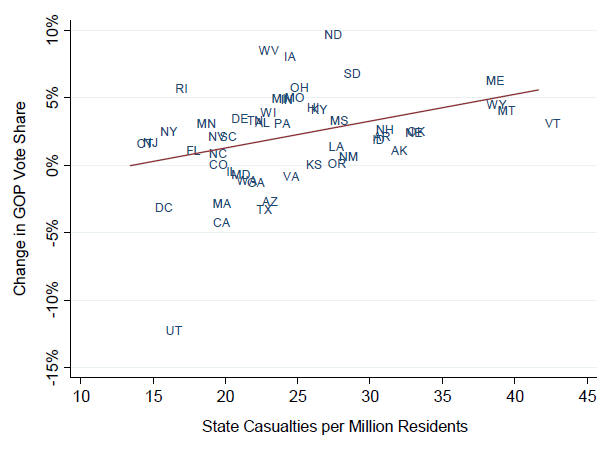

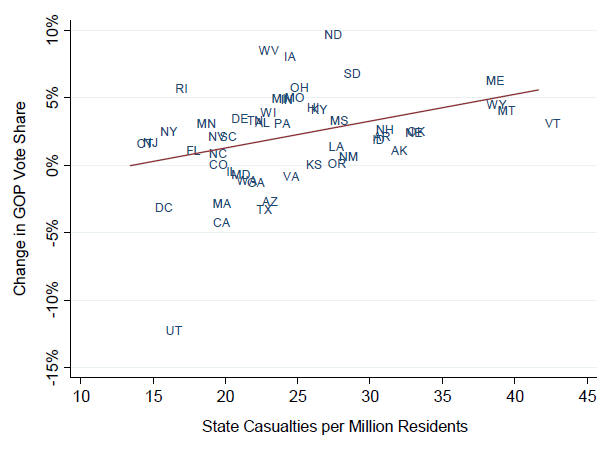

Because the relationship is easiest to visualize at the state level,

we first constructed a scatter plot showing each state's casualty

rate on the x-axis and the change in GOP vote share from 2012 to

2016 on the y-axis (Figure 1).

Trump out-performed Romney in forty of fifty states.

However, the

clear positive relationship shown in the scatter plot illustrates

Trump's ability to make electoral inroads among high casualty

states. 35

Figure 1

Trump's

Electoral Success in High Casualty States

How to read Figure 1:

Figure 1 illustrates that there is a direct

relationship between a state's combat casualty rate and the state's

support for Donald Trump.

As discussed in the main text, states that

experienced greater military sacrifice in the war in Iraq were more

likely to vote for Trump.

Additional statistical analysis confirms

that this relationship is robust, even when controlling for

alternative explanations.

Support for Trump, on the y-axis, is

measured as Trump's improvement (or decline) in state vote share as

compared to Mitt Romney in 2012. For example, 5% on the y-axis means

that Trump won 5% more of the state's votes in 2016 as compared to

Romney in 2012.

The state casualty rate, on the x-axis, is measured

as the per- capita (per 1 million) rate of soldiers from each state

who died in combat between 2001 and the 2016 election.

In an

additional analysis, we found that the same relationship holds when

we measure the total number of soldiers killed and wounded in

battle.

Could Trump's gains among high casualty states have tipped the

balance?

The data suggests it is possible. After all, Trump's

victory in the Electoral College depended on razor-thin margins in a

handful of key states. Central to Trump's victory was his ability to

flip three reliably blue states:

Pennsylvania, Michigan, and

Wisconsin.

Trump carried each of these states by less than 1%.

In

terms of their share of wartime sacrifice, all three of these states

experienced casualty rates in Iraq and Afghanistan that placed them

in the middle of the distribution, nation- wide. Michigan's casualty

rate was the national median, while Pennsylvania's casualty rate was

just above the median and Wisconsin's just below it.

What if each of

these states had suffered a lower casualty rate - for example, that

of neighboring New York?

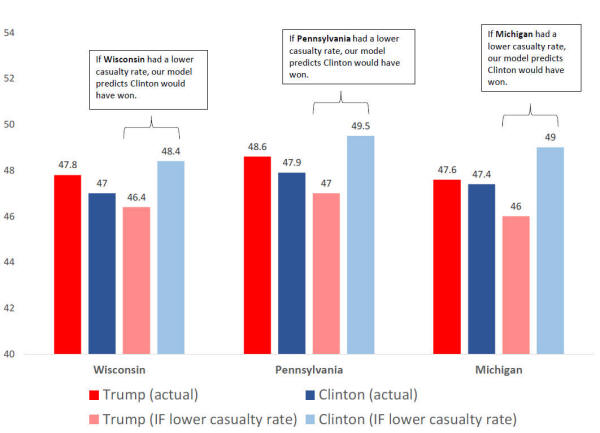

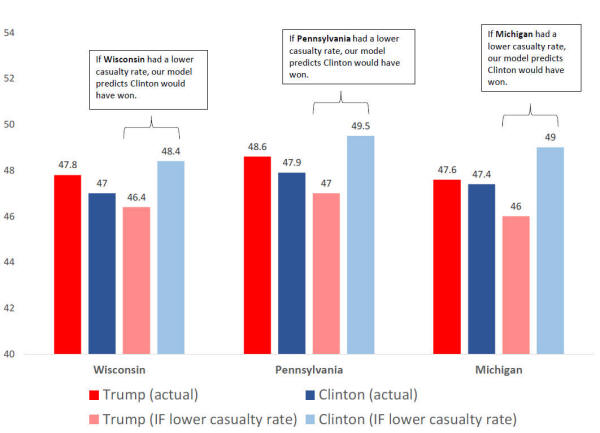

Figure 2 presents the estimates obtained from a simple regression

model. 36 In each state, our analysis predicts that Trump would have

lost between 1.4% and 1.6% of the vote if the state had suffered a

lower casualty rate.

As illustrated in Figure 2, such margins would

have easily flipped all three states into the Democratic column.

Trump's ability to connect with voters in communities exhausted by

more than fifteen years of war may have been critically important to

his narrow electoral victory.

Figure 2

How Lower Casualty Rates in

Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and

Michigan

might have cost Clinton the election

How to read Figure 2:

Figure 2, which is based on the predictive statistical model

discussed in the text, graphically examines what would have happened

in the 2016 Presidential election if Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and

Michigan had experienced a lower casualty rate.

The darker red and

darker blue bars on the left plot the actual vote percentage for

Trump and for Clinton.

The lighter red and lighter blue bars on the

right plot the predicted vote percentage, if each of these states

had a lower casual rate.

Our models suggest that

- if there had been a

lower casualty rate in each state - Trump would have lost all three.

However, most states are large, heterogeneous places.

The wartime

experiences and direct exposure to war costs of residents of upstate

and western New York, for example, may look very different from

those living in the New York City suburbs.

To account for these

intra- state differences and to paint a more nuanced picture, we

conducted a follow-up analysis of the relationship between Iraq and

Afghanistan war casualties and Trump's electoral success at the

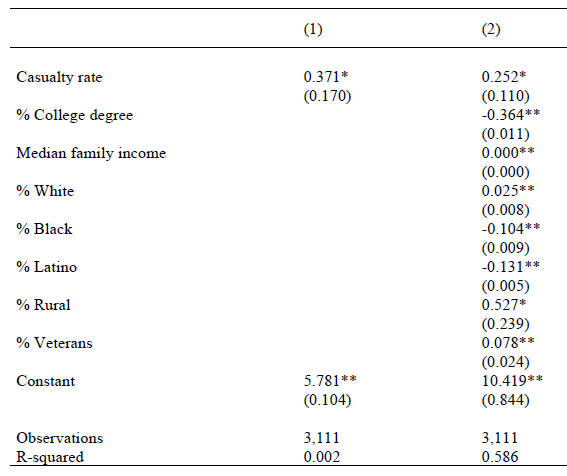

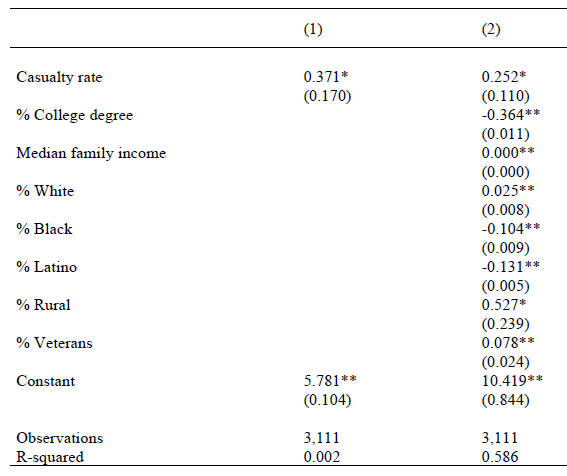

county level. The first column in Table 1 presents the results of a

bivariate ordinary least squares regression of the change in GOP

vote share from 2012 to 2016 on a county's casualty rate.

As in the

state-level analysis, the relationship is positive and statistically

significant. Trump was even more successful in surpassing Romney's

2012 performance in communities that had suffered disproportionately

high casualty rates.

Prior research has shown that Iraq and Afghanistan war casualties

are not randomly distributed across the country. Rather, they

correlate significantly with other demographics that might also

identify communities particularly receptive to Trump's candidacy.

37

To insure that county casualty rates are not just serving as a proxy

for another characteristic identifying counties predisposed to

support Trump to a greater degree than Romney, we estimated a second

regression model including a number of control variables.

Perhaps

most importantly, because prior research has shown that recent war

casualties have hailed disproportionately from communities with

lower levels of income and educational attainment, we control for

each county's median family income and percentage of adult residents

with a college degree.

Exit polls from 2016 showed that Trump

performed well among voters without a college degree; as a result,

this is a particularly important control. 38

In addition to income and education, we also included three

variables indicating each county's racial composition: the

percentage of residents that were white, black, or Latino. Trump

struggled to connect with African American voters, and his hard-line

immigration policies alienated him from many Latinos.

As a result,

we expect Trump to struggle making electoral inroads in counties

with large non-white populations.

Finally, we control for the percentage of each county's population

that lives in rural areas, as well as the percentage of each

county's population that are military veterans. The results are

presented in column 2 of Table 1.

Even after including all of these demographic control variables, the

relationship between a county's casualty rate and Trump's electoral

performance remains positive and statistically significant.

Trump significantly

outperformed Romney in counties that shouldered a disproportionate

share of the war burden in Iraq and Afghanistan. 39

IV - Looking

Ahead - An Electoral Check on Military Adventurism?

When President Obama won in 2008, pundits regularly discussed

frustration with the Iraq War as a factor motivating voters.

Yet

when Obama won re-election in 2012 the wartime narrative was not as

prominent. And in the post-election analysis of the 2016 cycle,

discussion of war fatigue has been all but absent.

This oversight

may plausibly be due to the fact that most American elites in the

chattering class have not, at least in recent years, been directly

affected by on-going conflicts. Children of elites are not as likely

to serve and die in the Middle East, and

elite communities are thus less likely to make this a point of

conversation.

The costs of war remain largely hidden, and an

invisible inequality of military sacrifice has taken hold. 40

Our

analysis in this paper suggests that Trump recognized and

capitalized on this class-based divergence. His message resonated

with voters in communities who felt abandoned by traditional

politicians in both parties.

If our interpretation of the data is correct, what does this mean

for the future of policymaking in the Trump administration? Trump's

surprise victory has raised pressing questions about how the

political neophyte will exercise his newfound political power.

During the campaign, scores of national security experts, including

many prominent Republicans, publicly denounced Trump, warning that

he possessed neither the knowledge base nor the temperament to lead

the world's most powerful military. 41

In his first months in office,

Trump's continued cavalier rhetoric concerning nuclear weapons and a

renewed arms race, coupled with controversial national security

staffing decisions - such as removing the chairman of the Joint

Chiefs and the Director of National Intelligence from the National

Security Council's principals committee and to elevate former

Breitbart CEO and political adviser Steve Bannon to the same body

- did little to assuage such concerns. 42

As of this writing in June 2017, Trump has significantly increased

bombing of ISIS targets in Iraq and Syria. 43

This includes dropping

the Massive Ordnance Air Blast (MOAB) bomb, known as the

"mother of

all bombs." While these actions were criticized by some, they also

drew bi-partisan support because some of the bombs were in reaction

to gas attacks carried out by Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

Congress and the courts are unlikely to offer a significant check on

President Trump's unilateral authority to direct the nation's

military policy. While Congress possesses the constitutional powers

needed to provide such a check, perhaps foremost the power of the

purse, it often lacks the political will to use them. This will

almost certainly be the case for the foreseeable future with

Republicans in charge of both chambers of Congress.

Courts can, and

have, struck down some executive actions that exceed constitutional

limits on executive power, even in the military realm.

However,

these cases are limited in number and scope. As a result, public

opinion and, ultimately, the ballot box may be the strongest check

on presidential recklessness.

All presidents consider the likely judgment of voters, both for

their own reelection and for the prospects of a co-partisan

successor who can defend their legacies. However, the significant

inroads that Trump made among constituencies exhausted by fifteen

years of war - coupled with his razor thin electoral margin (which

approached negative three million votes in the national popular

tally) - should make Trump even more cautious in pursuing ground

wars.

Trump, of course, has already proven in his first 100 days

that conventional wisdom (and conventional political theory) may not

apply to his administration. However, Trump has plainly demonstrated

keen electoral instincts and may well think twice before taking

actions that risk alienating an important part of his base.

Our results also have important implications for Democrats.

Currently the Democratic Party is engaging in a period of fitful

soul searching in a quest to understand its inability to connect

with many working class and rural voters who abandoned the party of

Roosevelt for

Trump.

Much of this introspection has focused on the party's

position on trade policy, economic inequality, and emphasis on

identity politics.

However, Democrats may also want to reexamine

their foreign policy posture if they hope to erase Trump's electoral

gains among constituencies exhausted and alienated by fifteen years

of war.

Table 1:

County Casualty Rates and Change in GOP Vote Share,

2012-2016

Note:

Table 1 presents

the results of ordinary least squares regression in which dependent

variable is the change in GOP share of the two-party vote from 2012

to 2016. Standard errors in parentheses. All significance tests are

two-tailed.

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.01

References

-

For data on the

number of Americans who died or were wounded in the Iraq and

Afghanistan wars, see:

https://www.dmdc.osd.mil/dcas/pages/casualties.xhtml.

For an estimate of the number of Americans who have served

in theater, see:

http://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/costs/human/veterans

-

For an analysis

of the election forecast models, see James E. Campbell, et

al, A Recap of the 2016 Election Forecasts, 50 POLITICAL

SCIENCE & POLITICS 331 (2017).

-

AMIE PARNES &

JONATHAN ALLEN, SHATTERED: INSIDE HILLARY CLINTON'S DOOMED

CAMPAIGN (2017)

-

On Clinton's

messaging failures, see Molly Ball, Why Hillary Clinton Lost

(The Atlantic, Nov 15, 2016); on Trump's connection with an

angry electorate, see: Jeff Guo, A New Theory for Why Trump

Voters Are So Angry - That Actually Makes Sense (Washington

Post, Nov 8, 2016).

-

Brad Schiller,

Op-Ed: Why did Trump win? The Economy, Stupid (Los Angeles

Times, Nov 9, 2016).

-

Even prior to the

election, we were on record as suggesting this might be the

case. As one of us said in a radio interview in September,

"… it will be very interesting to see after the election …

the extent to which this group [overlooked, primarily white,

working class veterans] and others like them found a voice

in the Trump campaign… Trump is speaking, in part, to a

group who hasn't found their voice heard by other

politicians."

http://www.accessminnesotaonline.com/2016/09/28/invisible-inequality-in-the-military/

-

DOUGLAS L. KRINER

& FRANCIS X. SHEN, THE CASUALTY GAP (2010).

-

See, infra, Part

II.

-

Richard

Eichenberg, Richard Stoll & Matthew Lebo, War President: The

Approval Ratings of George W. Bush, 50

J. CONFLICT RESOL. 783 (2006); Christopher Gelpi, Peter D.

Feaver & Jason Reifler, Success Matters: Casualty

Sensitivity and the War in Iraq, 30 INT'L SECURITY 7

(2005/2006); Erik Voeten & Paul Brewer, Public Opinion, the

War in Iraq, and Presidential Accountability, 50 J. CONFLICT

RESOL. 809 (2006); Matthew A. Baum & Tim Groeling, Reality

Asserts Itself: Public Opinion on Iraq and The Elasticity Of

Reality, 64 INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION 443 (2010).

-

David Karol &

Edward Miguel, The Electoral Cost of War: Iraq Casualties

and the 2004 U.S. Presidential Election, 69 J. Pol. 633

(2007).

-

Douglas L. Kriner

& Francis X. Shen, Iraq Casualties and the 2006 Senate

Elections, 32 LEGIS. STUD. Q. 507, 516-23 (2007); Scott

Sigmund Gartner & Gary M. Segura, All Politics Are Still

Local: The Iraq War and the 2006 Midterm Elections, 41 POL.

SCI. & POL. 95 (2008).

-

Christian Grose &

Bruce Oppenheimer, The Iraq War, Partisanship, and Candidate

Attributes: Explaining Variation in Partisan Swing in the

2006 U.S. House Elections, 32 LEGIS. STUD. Q. 531 (2007)

-

This pattern is

not unique to the Iraq War. Previous research has shown how

voters in high casualty constituencies have punished

incumbents associated with the war in conflicts ranging from

the Civil War (Carson, Jenkins, Rohde, and Souva 2001), to

Korea (Kriner and Shen 2010), to Vietnam (Gartner, Segura,

and Barratt 2004; Kriner and Shen 2010).

-

Scholarship on

military recruiting has long emphasized the importance of

economic incentives, in addition to patriotism. Even today,

as the Army struggles to retain experienced soldiers, it is

significantly increasing re-enlistment bonuses, while the

Air Force is considering resorting to "stop-loss" orders to

compel pilots to remain in the force even after their terms

of service conclude. Lolita Baldor, "Needing Troops, Army

Offers up to $90k Bonuses to Reenlist," (Associated Press,

June 6, 2017),

http://www.startribune.com/needing-troops-army-offers-up-to-90k-bonuses-to-re-enlist/426780681/.

John Donnelly, "Stop-Loss an Option for Air Force to Keep

Departing Pilots," (Roll Call¸ April 10, 2017),

http://www.rollcall.com/news/policy/stop-loss-option-air-force-keep-departing-pilots.

-

Kriner & Shen

(2010); DENNIS LAICH, SKIN IN THE GAME: POOR KIDS AND

PATRIOTS (2013); KATHY ROTH- DOUQUET & FRANK SCHAEFFER,

AWOL: THE UNEXCUSED ABSENCE OF AMERICA'S UPPER CLASSES FROM

MILITARY SERVICE - AND HOW IT HURTS OUR COUNTRY (2007).

-

Jamie Carson et

al., The Impact of National Tides and District-Level Effects

on Electoral Outcomes: The U.S. Congressional Elections of

1862-63, 42 Am. J. Pol. Sci. 887 (2001)

-

Kriner & Shen

(2010).

-

Scott Sigmund

Gartner, Gary M. Segura & Bethany A. Barratt, War

Casualties, Policy Positions, and the Fate of Legislators,

53 POL. RES. Q. 467 (2004); Kriner & Shen (2010).

-

Douglas L. Kriner

& Francis X. Shen, Invisible Inequality: The Two Americas of

Military Sacrifice, 46 U. MEM. L. REV. 545 (2016).

-

For instance, in

his speech Trump said: "We have an Army that hasn't been in

this position since World War II, in terms of levels and in

terms of readiness and in terms of everything else. We are

not capable like we have to be. This will be one of my most

important elements. When I talk cost cutting, I do for so

many different departments where the money is pouring and

they don't even know what to do with it. But when it comes

to the military we have to enhance our military. It's

depleted. That's the word I tend to use. It's a depleted - we have a very depleted military. We have great people, we

have a depleted military. I told you about the jet fighters.

Well it's like that with so many other things. So we are

going to take care of our military. We're going to take care

of our military - the people in our military, the finest

people we have." Remarks at a panel hosted by the Retired

American Warriors PAC in Herndon, Va., Oct 3, 2016. Online:

http://time.com/4517279/trump-veterans-ptsd-transcript/

-

See also Trump's

speech on April 27, 2016 at an event hosted by the National

Interest:

http://nationalinterest.org/feature/trump-foreign-policy-15960

-

Whether or not

Trump had actually been against the war originally was a

matter of dispute. See, e.g., Tim Murphy, What Did Donald

Trump Say on the Iraq War and When Did He Say It? (Mother

Jones, Sept 26, 2016).

-

"The CBS News

Republican Debate Transcript: Annotated." February 13, 2016,

Washington Post,

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/02/13/the-cbs-republican-debate-transcript-annotated/

-

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-politics/wp/2015/09/25/donald-trump-let-russia-fight-the-islamic-state-in-syria/

-

Trump's campaign

announcement speech on June 16, 2015:

http://time.com/3923128/donald-trump-announcement-speech/

-

Remarks on

Foreign Policy at the National Press Club on April 27, 2016:

http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=117813

-

John Mueller, The

Iraq Syndrome, 84 FOREIGN AFFAIRS 44 (2005).

-

Scott L. Althaus,

et al, When War Hits Home: The Geography Of Military Losses

And Support For War In Time And Space, 56 JOURNAL OF

CONFLICT RESOLUTION 382 (2012).

-

David Karol &

Edward Miguel, The Electoral Cost of War: Iraq Casualties

and the 2004 U.S. Presidential Election, 69 J. POL. 633

(2007); Douglas L. Kriner & Francis X. Shen, Iraq Casualties

and the 2006 Senate Elections, 32 LEGIS. STUD. Q. 507

(2007); Grose & Oppenheimer, supra note 12. Gartner and

Segura, supra note 11.

-

Karol & Miguel,

supra note 10; Kriner & Shen (2007), supra note 29; Kriner &

Shen (2010), supra note 7.

-

Specifically, we

use the casualty lists provided by the DoD for Operation

Enduring Freedom; Operation Freedom's Sentinel; Operation

Iraqi Freedom; and Operation New Dawn.

https://www.dmdc.osd.mil/dcas/pages/casualties.xhtml

-

State population

data taken from the 2016 U.S. Census, Population Division.

-

Military rules

stipulate that the home of record is each soldier's home at

the time of enlistment. By contrast, a soldier's "legal

residence" can be changed to the location in which they are

stationed if they intend to remain there.

https://www.army.mil/article/160640. The DoD records

provided (or we were able to identify if missing) home

county data for 6,475 service members. For most of the

remaining 257 service members, the DoD reported their home

county as "multiple," indicating that their home city of

record spanned multiple counties.

-

County-level

population estimates were obtained from the Census Bureau's

2015 American Community Survey.

-

Utah represents a

clear outlier in the scatter plot. Because the dependent

variable is the change in the two-party vote share, this is

not due to Evan McMullen's success as a third party

candidate in the state. Rather, it reflects Romney's

exceptional strength in heavily Mormon Utah in 2012, and

Trump's failure to connect with the same constituency in

2016. However, excluding Utah from the analysis yields

virtually identical results; for example, the bivariate

correlation coefficient decreases only slightly from r = .35

with Utah to r = .31 excluding it.

-

Estimates

obtained from a bivariate regression illustrated by the

best-fit line in the scatter plot presented in Figure 1.

Column 2 of Table 1 presents results from a multivariate

regression using county-level data.

-

Kriner & Shen

(2010), supra note 7; Kriner & Shen (2016), supra note 19.

-

https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/politics/2016-election/exit-polls/

-

Although not the

focus of our present investigation, it is worth noting that

the coefficients for many of the control variables also

accorded with expectations. Trump significantly

over-performed Romney in counties with greater percentages

of residents who did not hold a college degree. He

under-performed Romney in counties with higher African

American and Latino populations, but over-performed in

counties with larger white populations. Finally, Trump ran

ahead of Romney in rural communities as well as in

communities with large shares of military veterans.

-

Kriner & Shen

(2016), supra note 19.

-

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/08/08/us/politics/national-security-letter-trump.html

-

http://europe.newsweek.com/shuffle-national-security-council-players-lambasted-549892.

Note: This decision has since been reversed under new

National Security Adviser, H.R. MacMaster.

-

http://www.afcent.af.mil/Portals/82/Airpower Summary - March

2017.pdf?ver=2017-04-13-023039-397

|