|

Update

Multiple sources are claiming that Google is preparing a billion dollar investment into SpaceX that would give the company's nascent internet plan an enormous capital boost.

It's not clear what kind of ownership or stake Google would take in SpaceX as a result, but this move would likely replace the search giant's own research into providing online connectivity via weather balloons.

Google has previously hired satellite veterans to work on Project Loon; it's possible that the two companies would actively collaborate to design the future system.

Original article

Elon Musk held a SpaceX event over the weekend at which he announced plans for a new Seattle headquarters and unveiled a long-term proposal to build a high-speed, low-latency satellite system that would circle the entire planet with internet capability.

There are two kinds of people in this world - those who have never used satellite internet and those who loathe it.

Potential slogans for satellite providers like HughesNet include:

Sadly, it's a lot like this...

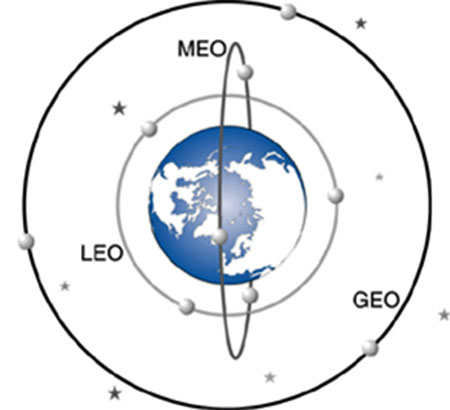

The reason typical satellite internet has such a terrible reputation is partially because of the inevitable latency. Satellite providers tend to use geostationary orbits, which sit 26,199 miles (on average) above sea level.

Typical minimum latency for an internet user tapping a geostationary satellite for connectivity is therefore in the 500-700ms range.

The advantage of using a geostationary orbit for satellite communication is that a relative handful of satellites can cover vast distances, and the ground arrays can use fixed dishes that don't need to rotate to track the satellite's position in the sky.

What Musk describes is something altogether different. Instead of a handful of fixed satellites, he's proposed building an array of satellites in low-Earth orbit at an altitude of approximately 750 miles.

This hypothetical system would be built at the new Seattle facility and is part of a long-term effort to revolutionize satellite design in much the same way that SpaceX has been attempting to reinvent rockets.

The long-term plan

Musk's goal, in the long term, is to finance the construction of a Mars city from such a satellite network while building a transmission system that can stretch the gap between the 'Red' Planet and our own.

The new network would focus on developing nations first, but would offer an option for first world countries as well. In theory, selling to the developed world could help boost sales in developing countries.

Musk thinks the entire network would require roughly 4000 satellites to operate at full capacity.

The explicit focus of this approach is to create a large network of relatively simple devices as opposed to the current "Big Satellite" model in which extremely complex, heavy, and expensive satellites are lofted into orbit to share signal across much of the planet but at substandard latencies and very high costs.

In theory, Musk's plan has something in common with Google's Project Loon and Facebook's drone research.

Both of these plans, however, are focused on the Earth-scale - how to extend more internet to more people, and by extension, secure more users for Google and Facebook's respective platforms. Musk, in contrast, is thinking much bigger - the long-term goal of his strategy is to fund an entire Mars exploration and colonization effort.

Details on this particular facet of the plan are scarce, but Musk isn't just talking about a handful of people - he wants to move millions of people and tons of cargo to Mars.

Critical to these plans is the idea that Musk can revolutionize the cost of putting satellites in space. Failure to do so is part of what doomed previous LEO efforts from companies like, These companies all attempted to bring LEO satellite networks online in the late 1990s to early 2000s, but the enormous costs of doing so bankrupted each (though both Globalstar and Iridium emerged from bankruptcy and were kept online, neither company ever rolled out the planned number of satellites or service plans).

Musk envisions this as a long-term plan, with launches beginning in five years and the network only coming fully online in 12-15 years.

That should be more than enough time to work out the kinks in Falcon's remote landing software - we'll see if that's enough to keep slashing the cost of launches and make such vast satellite networks a possibility.

|