Recently I handed over the keys to my email account to a service that promised to turn my spam-bloated inbox into a sparkling model of efficiency in just a few clicks.

Unroll.me's method of instant unsubscribing from newsletters and junk mail was "trusted by millions of happy users," the site said, among them the "Scandal" actor Joshua Malina, who tweeted in 2014:

"Your inbox will sing!"

Plus, it was free.

When a privacy policy popped up, I swatted away the legalese and tapped "continue."

Last month, the true cost of Unroll.me was revealed:

The service is owned by the market-research firm Slice Intelligence, and according to a report in The Times, while Unroll.me is cleaning up users' inboxes, it's also rifling through their trash.

When Slice found digital ride receipts from Lyft in some users' accounts, it sold the anonymized data off to Lyft's ride-hailing rival, Uber.

Suddenly, some of Unroll.me's trusting users were no longer so happy. One user filed a class-action lawsuit.

In a blog post, Unroll.me's chief executive, Jojo Hedaya, wrote that it was,

"heartbreaking to see that some of our users were upset to learn about how we monetize our free service."

He stressed,

"the importance of your privacy" and pledged to "do better."

But one of Unroll.me's founders, Perri Chase, who is no longer with the company, took a different approach in her own post on the controversy.

"Do you really care?" she wrote. "How exactly is this shocking?"

This Silicon Valley "good cop, bad cop" routine is familiar, and we spend our time surfing between these two modes of thought.

Chase is right:

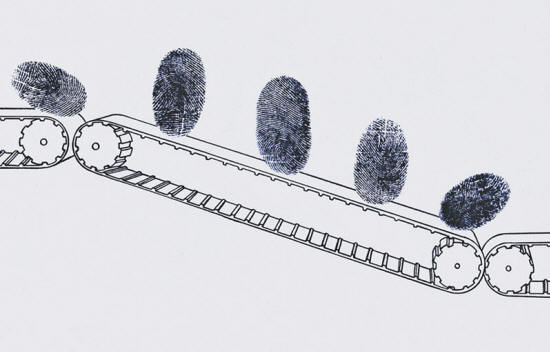

We've come to understand that privacy is the currency of our online lives, paying for petty conveniences with bits of personal information.

But we are blissfully ignorant of what that means.

We don't know what data is being bought and sold, because, well, that's private.

The evidence that flashes in front of our own eyes looks harmless enough:

We search Google for a new pair of shoes, and for a time, sneakers follow us across the web, tempting us from every sidebar.

But our information can also be used for matters of great public significance, in ways we're barely capable of imagining.

Privacy costs

often become clear

only after they've already

been paid.

When I signed up for Unroll.me, I couldn't predict that my emails might be strategic documents for a power-hungry company in its quest for total road domination.

Such privacy costs often become clear only after they've already been paid.

Sometimes a private citizen is caught up in a viral moment and learns that a great deal of information about him or her exists online, just waiting to be splashed across the news - like the guy in the red sweater who, after asking a question in a presidential debate, had his Reddit porn comments revealed.