|

by Jared Bennett

July 31,

2017

from

PublicIntegrity Website

Facebook is working on advanced facial recognition technology

to

identify users by creating digital faceprints.

The

company has begun lobbying state legislatures feverishly

to

protect its investments in the technology.

In re Facebook Biometric Information Privacy Litigation

Facebook's

massive facial recognition database grows each time

you tag a face to a person's name.

Does that give

FB the permanent right to catalog your face? What

about your clothing and posture?

All these can

be used to identify you on the street, without your

knowledge or consent.

Technocrats are

data addicts who can never get enough data.

Source

When Chicago

resident Carlo Licata joined Facebook in 2009, he did what

the 390 million other users of the world's largest social network

had already done:

He posted

photos of himself and friends, tagging the images with names.

But what Licata,

now 34, didn't know was that every time he was tagged, Facebook

stored his digitized face in its growing database.

Angered this was

done without his knowledge, Licata sued Facebook in 2015 as part of

a class action

lawsuit filed in Illinois state court accusing the company of

violating a one-of-a-kind Illinois law that prohibits collection of

biometric data without permission.

The suit is

ongoing...

Facebook denied the

charges, arguing the law doesn't apply to them. But behind the

scenes, the social network giant is working feverishly to prevent

other states from enacting a law like the one in Illinois.

Since the suit was

filed, Facebook has stepped up its state lobbying, according to

records and interviews with lawmakers.

But rather than

wading into policy fights itself, Facebook has turned to

lower-profile trade groups such as,

...to head off bills

that would give users more control over how their likenesses are

used or whom they can be sold to.

That effort is part

of a wider agenda.

Tech companies,

whose business model is based on collecting data about its users and

using it to sell ads, frequently oppose consumer privacy

legislation. But privacy advocates say Facebook is uniquely

aggressive in opposing all forms of regulation on its technology.

And the strategy

has been working. Bills that would have created new consumer data

protections for facial recognition were proposed in at least five

states this year,

-

Washington

-

Montana

-

New Hampshire

-

Connecticut

-

Alaska,

... but all failed, except the Washington bill, which

passed only after its scope was limited.

No federal law

regulates how companies use biometric privacy or facial recognition,

and no lawmaker has ever introduced a bill to do so.

That prompted the

Government Accountability Office to

conclude in

2015 that the,

"privacy issues

that have been raised by facial recognition technology serve as

yet another example of the need to adapt federal privacy law to

reflect new technologies."

Congress did,

however,

roll back privacy protections in March by allowing Internet

providers to sell browser data without the consumer's permission.

Facebook says on

its website it won't ever sell users' data, but the company is

poised to cash in on facial recognition in other ways.

The market for

facial recognition is forecast to grow to $9.6 billion by 2022,

according to analysts at Allied Market Research, as companies

look for ways to authenticate and recognize repeat customers in

stores, or offer specific ads based on a customer's gender or age.

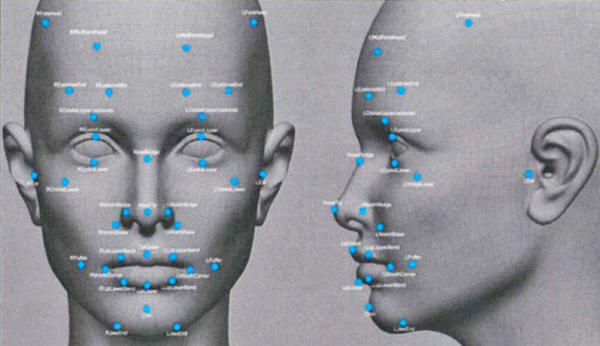

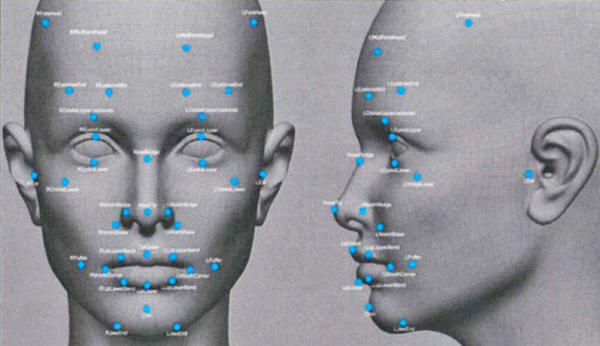

Facebook is working

on advanced recognition technology that would put names to faces

even if they are

obscured and identify people by their

clothing and posture.

Facebook has filed

patents for

technology allowing Facebook to tailor ads based on users'

facial expressions.

But despite the

relative lack of regulation, the technology appears to be worrying

politicians on both sides of the aisle, and privacy advocates too.

During a

hearing of the House Government Oversight Committee in March,

Chairman Jason Chaffetz, R-Utah, who left Congress in June,

warned facial recognition,

"can be used in

a way that chills free speech and free association by targeting

people attending certain political meetings, protests, churches

or other types of places in public."

Even one of the

inventors of facial recognition is worried.

"It pains me to

see a technology that I helped invent being used in a way that

is not what I had in mind in respect to privacy," said Joseph

Atick, who helped develop facial recognition in the 1990s at

Rockefeller University in New York City.

Joseph Atick,

now an industry consultant, is concerned that companies

such as Facebook will use the technology to identify individuals in public

spaces without their knowledge or permission.

"I can no

longer count on being an anonymous person," he said, "when I'm

walking down the street."

Atick calls for

federal regulations to protect people's privacy, because without it

Americans are left with,

"a myriad of

state laws," he said. "And state laws can be more easily

manipulated by commercial interests."

Facial

recognition is here

Facial

recognition's use is increasing. Retailers employ it to

identify shoplifters, and bankers want to use it to

secure bank accounts at ATMs.

The Internet of

things - connecting thousands of everyday personal objects from

light bulbs to cars - may use an individual's face to allow

access to household devices. Churches already use facial

recognition

to track

attendance at services.

Government is

relying on it as well. President Donald Trump staffed the U.S.

Homeland Security Department transition team with at least four

executives

tied to facial recognition firms.

Law enforcement

agencies run facial recognition programs using mug shots and

driver's license photos to identify suspects. About half of

adult Americans are

included in a facial recognition database maintained by law

enforcement, estimates the

Center on Privacy & Technology at Georgetown University Law

School.

To tap into

this booming business, companies need something only Facebook

has - a massive database of faces.

Facebook now

has

2 billion monthly users who upload about 350 million photos

every day - a "practically infinite" amount of data that

Facebook can use to train its facial recognition software,

according to a

2014 presentation by an engineer working on

DeepFace,

Facebook's in-house facial-recognition project.

"When we

invented face recognition, there was no database," Atick

said.

Facebook has,

"a system that could recognize the entire

population of the Earth."

Facebook says

it doesn't have any plans to directly sell its

database.

"We do not

sell people's facial recognition template or make them

available for use by developers or advertisers, and we have

no plans to do so," Facebook spokesman Andy Stone said in an

email.

But Facebook

currently uses facial recognition to organize photos and to

support its research into artificial intelligence, which

Facebook hopes will lead to new platforms to place more focused

targeted ads, according to public announcements made by the

company.

The more

Facebook can recognize what is in users' photographs using

artificial intelligence, the more they can learn about users'

hobbies, preferences and interests - valuable information for

companies looking to pinpoint sales efforts.

For example, if

Facebook identifies a user's face and her friends hiking in a

photo, it can use that information to place ads for hiking

equipment on her Facebook page, said Larry Ponemon,

founder of the

Ponemon

Institute, a privacy and security research and consulting

group.

"The whole

Facebook model is a commercial model," Ponemon said,

"gathering information about people and then basically

selling them products" based on that information.

Facebook hasn't

been consistent about what it plans to do with its facial data.

In 2012, at a

hearing of the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Privacy,

Technology and the Law, then-Chairman

Al Franken, D-Minn., asked Facebook's then-manager of

privacy and public policy, Rob Sherman, to assure users

the company wouldn't share its faceprint database with third

parties.

Sherman

declined.

"It's

difficult to know in the future what Facebook will look like

five or 10 years down the road, and so it's hard to respond

to that hypothetical," Sherman said.

And in 2013,

Facebook Chief Privacy Officer Erin Egan

told Reuters,

"Can I say

that we will never use facial recognition technology for any

other purposes [other than suggesting who to tag in photos]?

Absolutely not."

Egan added,

though, that if Facebook did use the technology for other

purposes the firm would give users control over it.

BIPA

Nearly a decade

ago, when facial recognition was still in its infancy, Illinois

passed the Biometric Information and Privacy Act (BIPA) of 2008 after a

fingerprint-scanning

company went bankrupt, putting the security of the biometric

data the company collected in doubt.

The

law requires companies to obtain permission from an

individual before collecting biometric data, including,

"a retina

or iris scan, fingerprint, voiceprint, or scan of hand or

face geometry."

It also

requires companies to list the purpose and length of time the

data will be stored and include those details in a written

biometric privacy policy.

If a business

violates the law, individuals can sue the company, a

provision that no other state privacy law permits.

"The

Illinois law is a very stringent law," said Chad Marlow,

policy counsel at the American Civil Liberties Union.

"But it's

not inherently an unreasonable law. Illinois wanted to

protect its citizens from facial recognition technologies

online."

That may

include, possibly, Facebook's Tag Suggestions application.

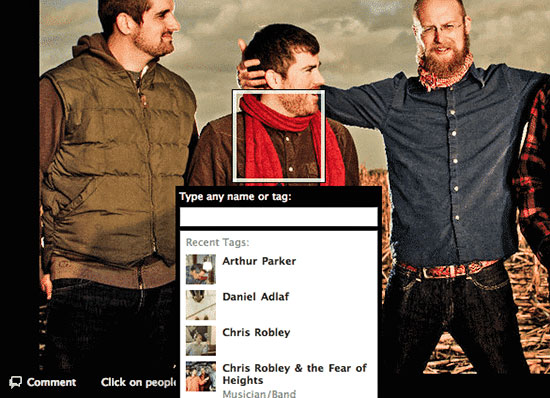

First

introduced in 2010, Tag Suggestions allows Facebook users to

label friends and family members in photos with their name using

facial recognition. When a user tags a friend in a photo or

selects a profile picture, Tag Suggestions

creates a personal data profile that it uses to identify

that person in other photos on Facebook or in newly uploaded

images.

Facebook

started quietly enrolling users in

Tag Suggestions in 2010 without informing them or obtaining

their permission.

By June 2011,

Facebook announced it had enrolled all users, except for a few

countries.

That's

what upset Licata, who works in finance in Chicago.

In the

lawsuit against Facebook, which names two other

plaintiffs, Licata alleges that every time he was tagged

in an image or selected a new profile picture, Facebook,

"extracted from those photographs a unique faceprint

or 'template' for him containing his biometric

identifiers, including his facial geometry, and

identified who he was,"

according to the lawsuit.

"Facebook

subsequently stored Licata's biometric identifiers

in its databases."

The

other plaintiffs also claim that by using their data to

build

DeepFace, Facebook deprived them of the monetary

value of their biometric data.

The

statute carries penalties up to $5,000 per violation,

which potentially could include thousands of Illinois

residents.

Licata

declined an interview request through the law firm

representing him, Chicago-based

Edelson PC, which

specializes in suing technology companies over privacy

violations.

The

firm's founder, Jay Edelson, is a controversial

figure. Some technologists and colleagues view him as an

opportunist - a "leech tarted up as a freedom fighter" -

according to a New York Times

profile.

Facebook declined the Center for Public Integrity's

requests to comment on the lawsuit specifically, but

said in an email that,

"our work demonstrates our commitment to protecting

the over 210 million Americans who use our service."

Facebook told

The New York Times in 2015 that the BIPA

lawsuit,

"is

without merit, and we will defend ourselves

vigorously."

Facebook says users can turn off Tag Suggestions, but

critics say the process is complex, making it likely the

feature will remain active.

And

many Facebook users don't even know data about their

likenesses are being stored.

"As

a person who has been tagged, there should be some

agreement at least that this is acceptable" before

Facebook enrolls users in Tag Suggestions, said

privacy researcher Ponemon.

"But the train has left the station."

In

2016, just 21 days after the judge in the Licata case

ruled against a Facebook motion that the Illinois law

only applies to in-person scans, not images or video,

an amendment to BIPA that would have defined facial

scans just that way was offered in the state Senate.

After

consumer groups such as the

World Privacy Forum and the

Illinois Public Interest Research Group wrote

letters of opposition, the measure was withdrawn by its

sponsor, state Sen. and Assistant Majority Leader

Terry Link, D-Vernon Hills. Link did not respond to

requests for comment.

Facebook has expressed support for the amendment, but

won't confirm or deny their involvement in the attempt.

The

effort fits a pattern, said Alvaro Bedoya,

executive director of the

Center on Privacy & Technology at Georgetown

University.

"Their approach has been, 'If you sue us, it doesn't

apply to us; if you say it does apply to us, we'll

try to change the law'," Bedoya said.

"It

is only laws like Illinois' that could put some kind

of check on this authority, so it is no coincidence

that [Facebook] would like to see this law undone.

This is the strongest privacy law in the nation. If

it goes away, that's a big deal."

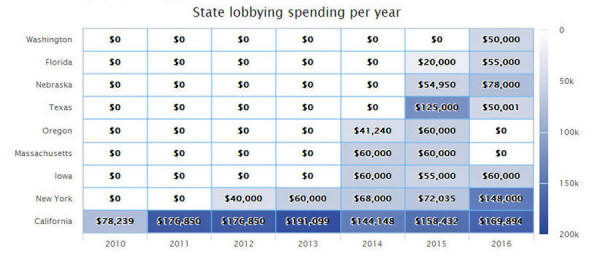

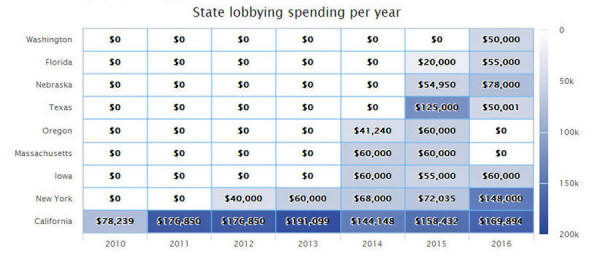

Facebook's state lobbying spending grows

Source:

National Institute on Money in State

Politics

Facebook's

hidden lobbying

Facebook

started

lobbying the federal government in earnest around 2011, when

it reported spending nearly $1.4 million.

By 2016, the

amount grew more than five times, to almost $8.7 million, when

Facebook lobbied on issues such as data security, consumer

privacy and tax reform, according to the

Center for Responsive Politics.

Facebook spends

much less to influence state lawmakers.

According to

reports compiled by the

National Institute on Money in State Politics, it spent

$670,895 on lobbying in states in 2016, a 64 percent jump from

$373,388 in 2014. Facebook has an active presence in a handful

of states - primarily California and New York - but it only

hired its first lobbyist in Illinois for

this year's session.

Facebook

prefers to work through trade associations to influence policy.

Sources in the

Illinois Legislature told the Center for Public Integrity that

the BIPA amendment attempt, which would have redefined facial

recognition, was led by

CompTIA, a trade

group that bills itself as,

"the

world's leading tech association."

CompTIA

declined to comment in detail, but confirmed that Facebook is

among its members.

Facebook

declined to comment about whether it was behind the amendment.

When Edelson lawyers asked for information about Facebook's

lobbying related to BIPA, Facebook's lawyers successfully

requested the court to seal those records, keeping the

information private.

On its website,

Facebook says it is a member of

56 groups and 108 third-party organizations that it works

with,

"on issues

relating to technology and Internet policy."

CompTIA,

despite acknowledging Facebook is a member, isn't on the list.

At the Facebook

annual shareholders meeting in Redwood City, California, last

month, more than 90 percent of the shares voted

were opposed to a proposal that would have required the

company to provide more information about its political

associations, including grass-roots lobbying.

CompTIA, which

absorbed the Washington, D.C.-based tech advocacy group

TechAmerica in 2015, employs one permanent lobbyist in Illinois

and contracts with the Roosevelt Group, one of Illinois' "super

lobbyists," which last year represented lobbying powerhouses

AT&T Illinois, payday lender PLS Financial Services and the

influential Illinois Retail Gaming & Operators Association.

In August 2016

CompTIA published a blog

post about the practical applications of biometrics, and

labeled BIPA "problematic" because terms such as "consent" and

"facial recognitions" are vaguely defined and it,

"invites an

avalanche of litigation."

CompTIA made

political contributions to just two non-candidate groups in 2016

- in the two states with the strictest privacy laws, Illinois

and Texas, according to the

National Institute of

Money in State Politics.

CompTIA gave

$21,225 last year to the Illinois Democratic Party.

CompTIA also

gave

$5,000 to the Republican Party in Texas, where Republican

Attorney General

Ken Paxton is charged with enforcing the state's biometric

privacy regulations, according to the institute.

Texas enacted

one of the stricter

biometric privacy laws in the nation. Signed in 2009, the

law requires companies to obtain an individual's permission to

capture a biometric identifier such as a facial image.

But unlike

Illinois' law, it doesn't allow state residents to sue and

leaves the enforcement authority solely with the attorney

general. The Texas attorney general's office declined to comment

on whether it has pursued lawsuits on biometric privacy

violations.

There's no

indication that Paxton's office has ever completed an

investigation, according to a review of records.

'They will

descend on you'

...proposed biometric privacy laws this past

legislative session, but all failed except for a weakened

version that survived in Washington.

Two other

states -

Arizona and

Missouri -

proposed narrower bills that provide privacy protections just

for students, but both fizzled out in committee.

Illinois tabled

a proposed

amendment to BIPA that would have strengthened the law by

barring companies from making submission of biometric data a

requirement of doing business.

...had a hand in blocking or weakening the biometric

privacy bills in Montana, Washington and Illinois, according to

a Center for Public Integrity review.

What happened

in Montana is typical. Katherine Sullivan, a small business

owner and intellectual privacy lawyer turned privacy advocate,

helped write a

biometric privacy bill that Democrat Rep. Nate McConnell

introduced this year in the Montana Legislature.

"Everyone I

talked to as a citizen thought it was a good idea," Sullivan

said.

Still, Sullivan

said she was warned that lobbyists representing powerful

companies would come out against the law.

"'They will

descend on you'," Sullivan said she was told.

The Montana

bill was introduced Feb. 17 and assigned to the House Judiciary

Committee.

Only one

hearing on the bill was held, on Feb. 23. Lobbyists from

Verizon, the Internet Coalition, which represents Internet and

ecommerce companies including Facebook, and the Montana Retail

Association showed up in opposition to the bill.

At the hearing,

Jessie Luther, a lobbyist from Verizon, read a letter

signed by,

-

CompTIA

-

the

Internet Coalition

-

TechNet, a network of

chief executives from technology companies

-

the

State Privacy and Security Coalition, a group of major

internet communications, retail and media companies

All three

count Facebook as a member.

The

letter, addressed to state Rep. Alan Doane, chairman

of the Judiciary Committee, warned that the proposed ,

"would

put Montana residents and businesses at much greater risk of

fraud, as well as open the door to wasteful class action

lawsuits against Montana businesses that receive biometric

data."

It also warned

that the bill would prevent using biometrics for "beneficial

purposes" such as accessing and securing personal accounts.

Doane said in an interview he

doesn't remember the letter, but agreed with many of its points.

On Feb. 27, the bill was tabled in committee.

Facial recognition, WhatsApp and

Facebook's

privacy record

The

'NRA approach'

Tough

privacy legislation that would have prohibited the

collection of biometric information without prior

consent and allow individuals to sue companies that

violate the law also fizzled out in

New Hampshire and

Alaska.

A

weaker bill in

Connecticut would have prohibited brick-and-mortar

stores from using facial recognition for marketing

purposes died in committee.

Washington's law

requires companies to obtain permission from customers

before enrolling their biometric data into a database

for commercial use and prohibits companies from selling,

leasing or otherwise handing the data over to a third

party without consent.

But it

does not allow individuals to sue companies directly.

More

important, some privacy advocates say, the law exempts

biometric data pulled from photographs, video or audio

recordings, similar to the amendment CompTIA had lobbied

for in Illinois as a way to weaken BIPA, which would

exempt Facebook's Tag Suggestions.

Earlier

versions of the law won the approval of big tech

companies such as Google and Microsoft Corp., and the

privacy advocacy group the

Electronic Frontier

Foundation.

But in

2016, EFF

pulled its support when the bill was amended to omit

"facial geometry," which Adam Schwartz, a senior

staff attorney at EFF, said would cover facial

recognition.

Schwartz said the final statute is weaker than BIPA

because the law's language is written in such a way that

it may allow companies to capture facial recognition

data without informed notice or consent.

The

statute,

"appears to have been tailored to protect companies

that are using facial recognition," Shwartz said.

Democratic state Rep. Jeff Morris, one of the

bill's sponsors, disagrees.

Morris

said the law covers any data that can be used to

identify a person by unique physical characteristics,

including applications that use,

"precise measurements between the bridge of your

nose and your eyes."

But

Morris said while most of the big tech companies such as

Microsoft, Amazon and Google supported the bill in its

final form, Facebook remained opposed.

Facebook's hired lobbyist in Washington - Alex Hur,

a former aide to state Speaker of the House Frank Chopp

- was,

"lobbying quite ferociously on the bill," Morris

said.

Facebook objected to the bill, he said, because it

included as protected data "behavioral biometrics,"

which refers to data on how a person moves, including an

individual's gait as recorded in videos.

Hur did

not respond to requests for comment.

One of

the trade groups working on Facebook's behalf in

Washington was the

Washington Technology Industry Association.

At a

hearing on the legislation in February, Jim

Justin, a WTIA representative, argued tagging

services like Facebook's should be exempt from the law.

"Given facial recognition, that data should be

protected," Justin said, "but if you are tagging

someone on Facebook and simply using their name, we

don't think that falls under what should be

protected, given that that person provided consent."

A

CompTIA lobbyist also spoke at the February hearing,

asking lawmakers to take a "limited approach" to

biometric privacy.

Morris

said CompTIA adopts what he calls the "NRA approach" to

lobbying.

"They basically say, 'You'll take our innovation out

of our cold, dead hands'," he said.

"This is a pretty common public-affairs tactic,"

Morris added, "an association that does the dirty

work so your company isn't tarnished."

'Didn't know they existed until…'

State

legislatures are beginning to recognize that many

personally identifying technologies may require

additional regulatory attention - and technology

companies such as Facebook and their trade groups are

gearing up to fight them.

Lawmakers in Illinois formed a committee this year to

discuss technology issues such as data privacy. The

CyberSecurity, Data Analytics and IT committee in

the Illinois House of Representatives held its first

hearing in March.

The

formation of the committee brought national attention to

Springfield.

"It

has brought in groups from D.C.," like the Internet

Association, said Rep.

Jaime Andrade Jr., D-Chicago, the committee's

chairman.

CompTIA

also has been "very active," he said.

"I

didn't know they existed until the committee"

formed, Andrade added. "As soon as the committee was

created they came in and introduced themselves."

|