|

The fear and stress, the anger and hatred, reduce all Afghans to the enemy, and this includes women, children and the elderly. Civilians and combatants merge into one detested nameless, faceless mass.

The psychological leap to murder is short. And murder happens every day in Afghanistan.

It happens in drone strikes, artillery bombardments, airstrikes, missile attacks and the withering suppressing fire unleashed in villages from belt-fed machine guns.

Military attacks like these in civilian areas make discussions of human rights an absurdity.

Robert Bales, a U.S. Army staff sergeant who allegedly killed 16 civilians in two Afghan villages, including nine children, is not an anomaly.

To decry the butchery of this case and to defend the wars of occupation we wage is to know nothing about combat. We kill children nearly every day in Afghanistan. We do not usually kill them outside the structure of a military unit. If an American soldier had killed or wounded scores of civilians after the ignition of an improvised explosive device against his convoy, it would not have made the news.

Units do not stick around to count their “collateral damage.”

But the Afghans know. They hate us for the

murderous rampages. They hate us for our hypocrisy.

This myth allows us to make sense of mayhem and death. It justifies what is usually nothing more than gross human cruelty, brutality and stupidity. It allows us to believe we have achieved our place in human society because of a long chain of heroic endeavors, rather than accept the sad reality that we stumble along a dimly lit corridor of disasters. It disguises our powerlessness.

It hides from view the impotence and ordinariness of our leaders.

But in turning history into myth we transform random events into a sequence of events directed by a will greater than our own, one that is determined and preordained. We are elevated above the multitude. We march to nobility. But it is a lie. And it is a lie that combat veterans carry within them.

It is why so many commit suicide.

When Ernie Pyle, the famous World War II correspondent, was killed on the Pacific island of Ie Shima in 1945, a rough draft of a column was found on his body.

He was preparing it for release upon the end of the war in Europe. He had done much to promote the myth of the warrior and the nobility of soldiering, but by the end he seemed to have tired of it all:

There is a constant search in all wars to find new perversities, new forms of death when the initial flush fades, a rear-guard and finally futile effort to ward off the boredom of routine death.

This is why during the war in El Salvador the death squads and soldiers would cut off the genitals of those they killed and stuff them in the mouths of the corpses. This is why we reporters in Bosnia would find bodies crucified on the sides of barns or decapitated. This is why U.S. Marines have urinated on dead Taliban fighters.

Those slain in combat are treated as trophies by their killers, turned into grotesque pieces of performance art.

It happened in every war I covered.

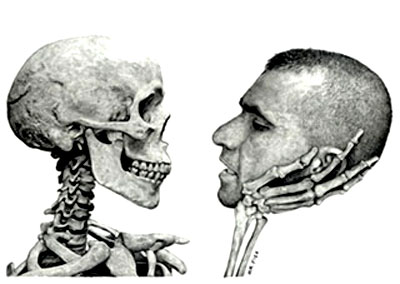

War perverts and destroys you.

It pushes you closer and closer to your own annihilation - spiritual, emotional and finally physical. It destroys the continuity of life, tearing apart all systems - economic, social, environmental and political - that sustain us as human beings. In war, we deform ourselves, our essence. We give up individual conscience - maybe even consciousness - for contagion of the crowd, the rush of patriotism, the belief that we must stand together as a nation in moments of extremity.

To make a moral choice, to defy war’s enticement, can in the culture of war be self-destructive. The essence of war is death. Taste enough of war and you come to believe that the stoics were right:

A World War II study determined that, after 60 days of continuous combat, 98 percent of all surviving soldiers will have become psychiatric casualties. A common trait among the remaining 2 percent was a predisposition toward having “aggressive psychopathic personalities.”

Lt. Col. Dave Grossman in his book “On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society,” notes:

During the war in El Salvador, many soldiers served for three or four years or longer, as in the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, until they psychologically or physically collapsed.

In garrison towns, commanders banned the sale of sedatives because those drugs were abused by the troops. In that war, as in the wars in the Middle East, the emotionally and psychologically maimed were common. I once interviewed a 19-year-old Salvadoran army sergeant who had spent five years fighting and then suddenly lost his vision after his unit walked into a rebel ambush.

The rebels killed 11 of his fellow soldiers in the firefight, including his closest friend. He was unable to see again until he was placed in an army hospital.

But the doctors told me that he had no head

wounds.

When we spend long enough in war, it comes to us

as a kind of release, a fatal and seductive embrace that can consummate the

long flirtation with our own destruction.

He stood over the body of his comrade, the commander Sava Kovacevic, and found:

War ascendant wipes out Eros. It wipes out delicacy and tenderness.

Its communal power seeks to render the individual obsolete, to hand all passions, all choice, all voice to the crowd.

When we see this, when we see our addiction for what it is, when we understand ourselves and how war has perverted us, life becomes hard to bear.

Jon Steele, a cameraman who spent years in war zones, had a nervous breakdown in a crowded Heathrow Airport after returning from Sarajevo. Steele had come to understand the reality of his work, a reality that stripped away the self-righteous, high-octane gloss.

When he was in Sarajevo he was,

A year after the end of the war in Sarajevo, I sat with Bosnian friends who had suffered horribly.

A young woman, Ljiljana, had lost her father, a Serb, who refused to join the besieging Serb forces around the city. A few days earlier she had to identify his corpse. The body was lifted, water running out of the sides of a rotting coffin, from a small park for reburial in the central cemetery.

Soon she would emigrate to Australia - where, she told me,

Ljiljana was young. But the war had exacted a toll.

Her cheeks were hollow, her hair dry and brittle. Her teeth were decayed and some had broken into jagged bits. She had no money for a dentist; she hoped to have them fixed in Australia. Yet all she and her friends did that afternoon was lament the days when they lived in fear and hunger, emaciated, targeted by Serb gunners on the heights above. They did not wish back the suffering.

And yet, they admitted, those may have been the

fullest days of their lives. They looked at me in despair. I had known them

when hundreds of shells a day fell nearby, when they had no water to bathe

in or wash their clothes, when they huddled in unheated flats as sniper

bullets hit the walls outside.

The old comradeship, however false, had vanished

with the last shot.

They depended on handouts from the international community. They understood that their cause, once as fashionable in certain intellectual circles as they were themselves, lay forgotten. No longer did actors, politicians and artists scramble to visit during the cease-fires - acts that were almost always ones of gross self-promotion.

They knew the lie of war, the mockery of their

idealism, and struggled with their shattered illusions. And yet, they wished

it all back, and I did, too.

It had no return address. I never heard from her

again. But many of those I worked with as war correspondents did not escape.

They could not break free from the dance with death. They wandered from

conflict to conflict, seeking always one more hit.

But those of us who had known him understood he

had been consumed.

His loss is a hole that will never be filled. His ashes were placed in Sarajevo’s Lion Cemetery, for the victims of the war. I flew to Sarajevo and met the British filmmaker Dan Reed. It was an overcast November day. We stood over the grave and downed a pint of whiskey. Dan lit a candle.

I recited a poem the Roman lyric poet Catullus had written to honor his dead brother.

It was there, among 4,000 war dead, that Kurt belonged.

He died because he could not free himself from war. He had been

trying to replicate what he had found in Sarajevo, but he could not. War

could never be new again. Kurt had been in East Timor and Chechnya. Sierra

Leone, I was sure, meant nothing to him.

|