|

by Max Roser

January 11,

2022

from

OurWorldInData Website

The

decline of global poverty

is one of the

most important

achievements in

history,

but the end of

poverty

is still very

far away...

The Reverend

Thomas Malthus asserted that poverty is inevitable.

"It has appeared that

from the inevitable laws of our nature, some human beings must

suffer from want. These are the unhappy persons who, in the

great lottery of life, have drawn a blank." 1

Writing in the 18th

century it is understandable that he came to this conclusion.

Poverty was such a persistent reality in humanity's history up to

then, that it was unimaginable that it could ever be different.

In the two centuries since Malthus' death we have learned however

that he was wrong.

The deep poverty of the past is not inevitable.

Economic growth is

possible and entire societies can leave the widespread poverty of

the past behind.

It is possible

to leave widespread poverty behind

Let's look at one of the societies that has achieved this.

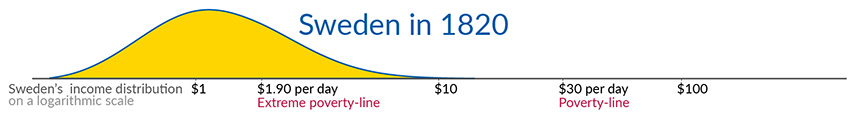

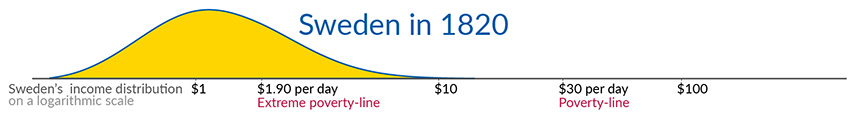

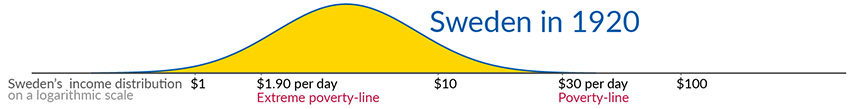

Two centuries ago, the

huge majority of people in Sweden lived in deep poverty.

Every

fourth child died,

and close to 90% of the population was so very poor that they could

not afford a tiny space to live, some minimum heating capacity, and

food that would not induce malnutrition. 2

Adjusted for inflation the income distribution looked like this:

3

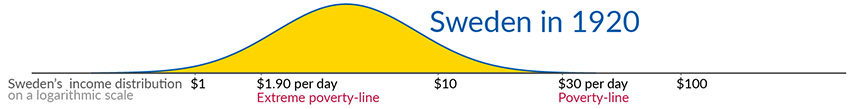

From the late 19th century onwards Sweden's economy increasingly

adopted modern production technology and achieved the productivity

gains that made economic growth possible.

A century ago Swedes were

still poor, but the majority had left the very worst poverty behind.

4

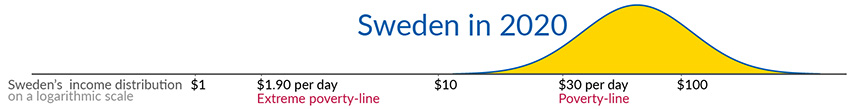

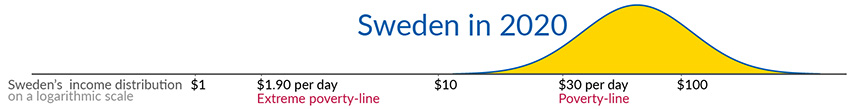

Today the poverty line in Sweden is set at about $30 per day (this

is adjusted for price differences between countries and measured in

international-dollars). 5

The

strong economic growth in the last century made it possible that

the majority of Swedes are living above the poverty line. 6

Sweden is one of the countries that achieved large growth and

thereby proved Malthus wrong.

The three distributions

show how the majority of Swedes left the deep poverty of the past

behind.

The majority

of the world is poor

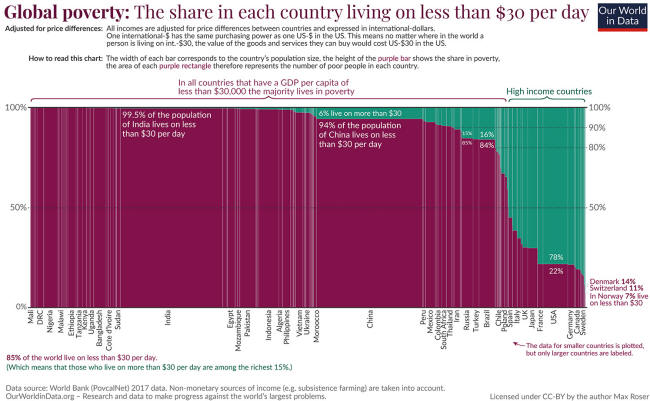

Other high-income countries adopted poverty lines very similar to

Sweden's poverty line of $30 a day.

And

as I documented before, the

size of social care payouts and proposals for Universal Basic

Incomes are also around $30 per day.

Just like the UN relies

on the $1.90 per day poverty line to track 'extreme poverty', I

therefore rely on the $30 a day threshold as a definition for

'poverty'.

It is based on the notion

of who is considered poor in the world's richer countries.

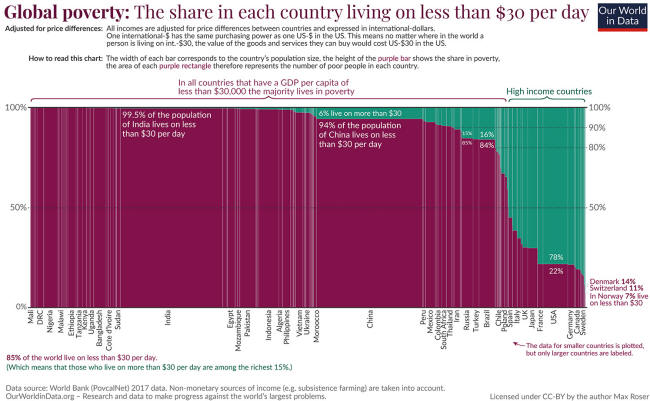

Taking into account the different price levels across countries, the

latest statistics show that 85% of the world population live below

this poverty line.

This large visualization shows where they live.

The height of the purple bar corresponds to the share in poverty in

each country.

I ordered the countries by income:

from the poorest

countries on the very left to the richest countries on the

right.

The width of each country

corresponds to the country's population size.

The only countries in which not nearly everyone lives in poverty are

high-income countries. GDP per capita is a measure of average income

that not only takes people's individual incomes, but also government

expenditure, into account. 7

As noted in the chart, in

all countries that have a GDP per capita of less than $30,000 the

majority of the population lives in poverty.

But the data also shows that in all countries a significant share

lives in poverty. No country, not even the richest countries, has

eliminated poverty.

There are no 'developed'

countries, there is work to do for all.

How far away

are we from a world in which no one lives on less than $30 a day?

The economic history of today's richest countries shows that

widespread poverty is not inevitable.

What needs to happen to

achieve the same for all people in the world?

The share in poverty in any country depends on two factors: the

average level of income and the level of inequality.

Some

countries

reduced inequality successfully and thereby reduced

poverty. Lower inequality in the future can further reduce

poverty.

But because

the average income in the majority of countries in the world

is much lower than $30-poverty-line, strong growth is

necessary for global poverty to decline.

I calculated

that at a minimum the world economy needs to increase

five-fold for global poverty to substantially decline.

This is in

a scenario in which the world would also achieve a massive

reduction in inequality: inequality between all the world's

countries would disappear entirely in this scenario.

It should

therefore be seen as a calculation of the minimum necessary

growth for an end of poverty.

A five-fold

increase of the global economy is certainly not easy to

achieve, but it is also not impossible - it is what the

world has achieved

in the last 5 decades, and the climate researchers of

the IPCC

expect even more growth for this century in their

'Sustainability Scenario', the scenario in which the world

is most successful in avoiding climate change.

8

That all of

the world will live on more than $30 a day might be hard to

imagine right now.

But then

it's good to remember that today's reality in high-income

countries was also entirely unimaginable very recently.

Two

centuries of progress and still a very long way to go

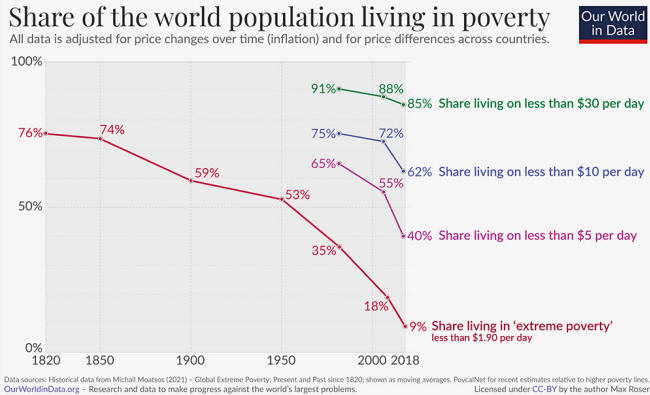

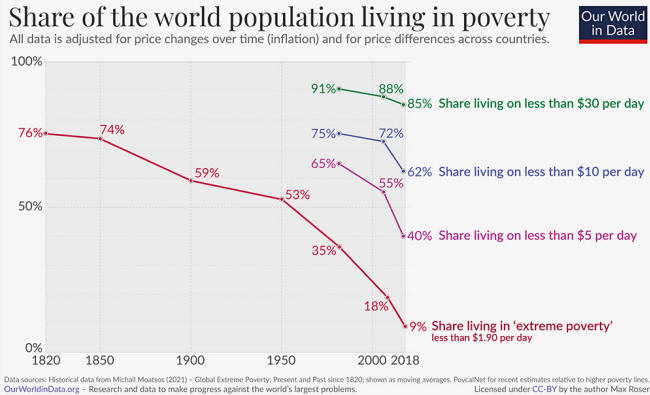

The final

chart summarizes the global history of poverty. It focuses

on the last two centuries when humanity

left the stagnation of the past behind and achieved

growth for the first time.

The world

made good progress - in the last decade the share that lives

on less than $10 per day has declined by 10 percentage

points - but the chart also shows that much progress is

still needed. 62% live on less than $10 per day and 85% live

on less than $30.

The global

data makes clear why the world needs much more growth to end

poverty. The world as a whole today is in a situation not so

different from Sweden a century ago.

The majority of the

world left extreme poverty behind, but is still far poorer

than $30 a day.

Even after

two centuries of the global fight against poverty we are

still in the early stages. The history of global poverty

reduction has only just begun.

Our World in

Data presents the data and research to make progress against the

world's largest problems.

This article draws on data and research discussed in our entry

on

Global Poverty...

Endnotes

-

Thomas

Malthus (1798) - An Essay on the Principle of Population.

Chapter X, paragraph 29, lines 12-15. Online

here.

-

Michail

Moatsos (2021) - Global extreme poverty: Present and past

since 1820. Published in OECD (2021), How Was Life?

Volume II: New Perspectives on Well-being and Global

Inequality since 1820, OECD Publishing, Paris,

https://doi.org/10.1787/3d96efc5-en.

-

The data

for the income distribution plotted below is produced by the

team of Gapminder - it is documented

here.

-

Moatsos

estimates that in 1920 a third of Sweden's population (34%)

still lived in extreme poverty.

-

Sweden's

median monthly income in 2017 was $1469 according to

PovcalNet. 60% of the median expressed in daily

income/consumption is (0.6*1469)/30=$29.38 per day

-

Much of

this progress was achieved in the recent past, since the

early 80s the share living on less than $30

has declined from 60% to 16%.

-

GDP per

capita is a more comprehensive measure of average incomes

and there are several reasons why it is typically higher

than the averages found in both income surveys and

expenditure surveys.

GDP

includes many items that are typically not measured in

household income surveys, such as an imputed rental value of

owner-occupied housing, the retained earnings of firms and

taxes on production such as VAT.

The gap is even larger when

GDP is compared to surveys of household consumption - the

latter concept excluding both investment expenditure and

government expenditure on public services such as education

and health.

Other

aggregates beyond GDP are available in the national accounts

that are more comparable to the concepts applied in

household income and consumption surveys.

However, important

differences still remain even here.

For example, in addition

to imputed rents, imputations for the value of certain

financial services, such as bank accounts, are included in

aggregate household consumption measured in national

accounts, with no equivalent for these items recorded in the

survey data. In many countries the consumption of 'nonprofit

institutions serving households' (NPISH) is included as part

of household consumption within national accounts, but not

within household surveys.

On top of

these conceptual differences are a range of mis-measurement

problems that affect both sets of data. On this topic see

Deaton (2005), and Pinkovskiy and Sala-i-Martin (2016).

Deaton,

Angus. 2005. "Measuring Poverty in a Growing World (or

Measuring Growth in a Poor World)." The Review of Economics

and Statistics 87 (1): 1–1.

Pinkovskiy,

Maxim, and Xavier Sala-i-Martin. 2016. "Lights, Camera…

Income! Illuminating the Nation"

-

In this

scenario global GDP per capita increases to $81,250.

|