|

by Mark Tseng-Putterman

June 20,

2018

from

Medium Website

Spanish version

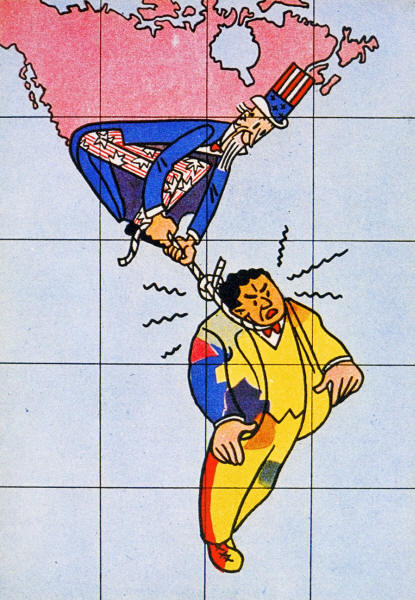

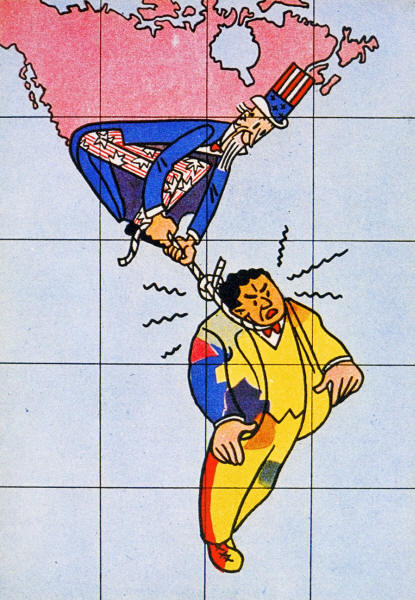

The 1823 Monroe Doctrine

set the

stage for U.S. intervention

throughout Latin America.

Photo

by Michael Nicholson/Corbis via Getty

Those

seeking asylum today

inherited a

series of crises

that drove them

to the border...

A national spotlight now shines on the border between the United

States and Mexico, where heartbreaking images of Central American

children being separated from their parents and held in cages

demonstrate the consequences of the

Trump administration's

"zero-tolerance policy" on unauthorized entry into the country,

announced in May 2018.

Under intense

international scrutiny, Trump has now

signed an executive order that will keep families detained at

the border together, though it is unclear when the more than 2,300

children already separated from their guardians will be returned.

Trump has promised

that keeping families together will not prevent his administration

from maintaining "strong-very strong, borders," making it

abundantly clear that the crisis of mass detention and deportation

at the border and throughout the U.S. is far from over.

Meanwhile,

Democratic rhetoric of inclusion, integration, and opportunity has

failed to fundamentally question the logic of Republican calls for a

strong border and the nation's right to protect its sovereignty.

At the margins of

the mainstream discursive stalemate over immigration lies over a

century of historical U.S. intervention that politicians and pundits

on both sides of the aisle seem determined to silence.

Since

Theodore Roosevelt in 1904

declared the U.S.'s "right" to exercise an "international police

power" in Latin America, the U.S. has cut deep wounds throughout the

region, leaving scars that will last for generations to come.

This

history of intervention is inextricable from the contemporary

Central American crisis of internal and international displacement

and migration...

The liberal

rhetoric of inclusion and common humanity is insufficient:

we must

also acknowledge the role that a century of U.S.-backed military

coups, corporate plundering, and neoliberal sapping of resources has

played in the poverty, instability, and violence that now drives

people from,

-

Guatemala

-

El Salvador

-

Honduras,

...toward Mexico and

the United States.

For decades, U.S.

policies of military intervention and economic neoliberalism have

undermined democracy and stability in the region, creating vacuums

of power in which drug cartels and paramilitary alliances have

risen.

In the past fifteen years alone,

CAFTA-DR - a free trade

agreement between the U.S. and five Central American countries as

well as the Dominican Republic - has

restructured the region's economy and guaranteed economic

dependence on the United States through massive trade imbalances and

the influx of American agricultural and industrial goods that weaken

domestic industries.

Yet there are few

connections being drawn between the weakening of Central American

rural agricultural economies at the hands of CAFTA and the rise in

migration from the region in the years since.

In general, the U.S.

takes no responsibility for the conditions that drive Central

American migrants to the border.

U.S. empire thrives on amnesia.

The Trump administration cannot remember what it said last week, let

alone the actions of presidential administrations long gone that

sowed the seeds of today's immigration crisis.

There can be no

common-sense immigration "debate" that conveniently ignores the

history of U.S. intervention in Central America.

Insisting on

American values of inclusion and integration only bolsters the very

myth of

American 'exceptionalism,' a narrative that has erased this

nation's imperial pursuits for over a century.

As the British

immigrant rights refrain goes,

"We are here

because you were there."

The adage holds no

less true here and now.

It's time to insist that accepting Central

American refugees is not just a matter of morality or American

benevolence. Indeed, it might be better described as a matter of

reparations.

The following timeline compiles

numerous sources to lay out an incomplete history of U.S. military

and economic intervention in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala

over the past century:

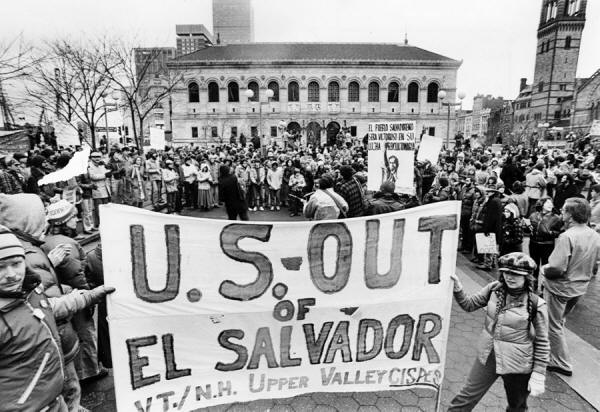

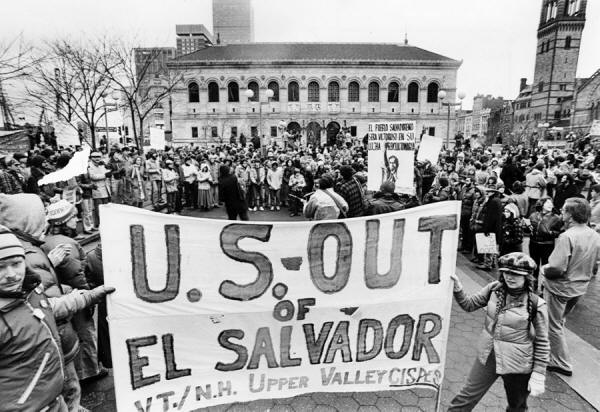

Anti-war marchers at Copley Square

on their way to Boston Common to protest

U.S. military involvement in El Salvador,

on March 21, 1981.

Photo by John Tlumacki

The Boston Globe via Getty

1932:

A peasant rebellion, led by Communist leader Farabundo Martí,

challenges the authority of the government. 10,000 to 40,000

communist rebels, many indigenous, are systematically murdered

by the regime of military leader Maximiliano Hernández Martínez,

the nation's acting president. The United States and Great

Britain, having bankrolled the nation's economy and owning the

majority of its export-oriented coffee plantations and railways,

send naval support to quell the rebellion.

1944:

Martínez is

ousted by a bloodless popular revolution led by students.

Within months, his party is reinstalled by a reactionary coup

led by his former chief of police, Osmín Aguirre y Salinas,

whose regime is legitimized by immediate

recognition from the United States.

1960:

A military-civilian junta promises free elections. President

Eisenhower withholds recognition, fearing a leftist turn. The

promise of democracy is broken when a right-wing countercoup

seizes power months later. Dr. Fabio Castillo, a former

president of the national university, would

tell Congress that this coup was openly facilitated by the

United States and that the U.S. had opposed the holding of free

elections.

1980–1992:

A civil war rages between the military-led government and the

leftist Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). The

Reagan administration, under its Cold War containment policy,

offers significant military assistance to the authoritarian

government, essentially running the war by 1983. The U.S.

military

trains key components of the Salvadoran forces, including

the Atlacatl Battalion, the "pride

of the United States military team in San Salvador." The

Atlacatl Battalion would go on to commit a civilian

massacre in the village of El Mozote in 1981, killing at

least 733 and as many as 1,000 unarmed civilians, including

women and children. An

estimated 80,000 are killed during the war, with the U.N.

estimating that 85 percent of civilian deaths were committed by

the Salvadoran military and death squads.

1984:

Despite the raging civil war funded by the Reagan

administration, a mere three percent of Salvadoran and

Guatemalan asylum cases in the U.S. are approved, as Reagan

officials

deny allegations of human rights violations in El Salvador

and Guatemala and designate asylum seekers as "economic

migrants." A religious sanctuary movement in the United States

defies the government by publicly sponsoring and sheltering

asylum seekers. Meanwhile, the U.S.

funnels $1.4 million to its favored political parties in El

Salvador's 1984 election.

1990:

Congress

passes legislation designating Salvadorans for Temporary

Protected Status. In 2018, President Trump would

end TPS status for the 200,000 Salvadorans living in the

United States.

2006:

El Salvador enters the

Dominican Republic-Central

America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR), a neoliberal

export-economy model that gives global multinationals increased

influence over domestic trade and regulatory protections.

Thousands of unionists, farmers, and informal economy workers

protest the free trade deal's implementation.

2014:

The U.S.

threatens to withhold almost $300 million worth of

Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) development aid unless El

Salvador ends any preferences for locally sourced corn and bean

seeds under its Family Agriculture Plan.

2015:

Under the tariff reduction model of CAFTA-DR,

all U.S. industrial and commercial goods enter El

Salvador

duty free, creating impossible conditions for domestic

industry to compete. As of 2016, the country had a

negative trade balance of $4.18 billion.

Honduran soldiers operate a mortar

for members of the U.S. Army 82nd Airborne Division

during a joint exercise, March 1988.

(Photo: Department of Defense, NARA)

1911:

American entrepreneur Samuel Zemurray partners with the deposed

Honduran President Manuel Bonilla and U.S. General Lee Christmas

to launch a

coup against President Miguel Dávila. After seizing several

northern Honduran ports, Bonilla wins the Honduran 1911

presidential election.

1912:

Bonilla

rewards his corporate U.S. backers with concessions that

grant natural resources and tax incentives to American

companies, including Vaccaro Bros. and Co. (now Dole Food

Company) and United Fruit Company (now Chiquita Brands

International). By 1914, U.S. banana interests would come to own

one million acres of the nation's best land - an ownership

frequently insured through the deployment of U.S. military

forces.

1975:

The United Fruit Company ( rebranded as the United Brands

Company)

pays $1.25 million to a Honduran official, and is accused of

bribing the government to support a reduction in banana export

taxes.

1980s:

In an attempt to curtail the influence of left-wing movements in

Central America, the Reagan administration stations thousands of

troops in Honduras to

train Contra right-wing rebels in their guerrilla war

against Nicaragua's Sandinistas. U.S. military aid reaches $77.5

million in 1984. Meanwhile, trade liberalization policies open

Honduras to the interests of global capital and disrupt

traditional forms of agriculture.

2005:

Honduras becomes the second country to enter CAFTA, the free

trade agreement with the U.S., leading to

protests from unions and local farmers who fear being

outcompeted by large-scale American producers. Rapidly, Honduras

goes from being a net agricultural exporter to a net importer,

leading to loss of jobs for small-scale farmers and increased

rural migration.

2009:

Left-leaning and democratically elected President Manuel Zelaya,

who pursued progressive policies such as raising the minimum

wage and subsidizing public transportation, is exiled in a

military coup. The coup is staged after Zelaya announces

intentions to hold a referendum on the replacement of the 1982

constitution, which had been written during the end of the reign

of U.S.-backed military dictator Policarpo Paz García. Honduran

General Romeo Vásquez Velásquez, a graduate of the U.S. Army

training program known as the School of the Americas (nicknamed

"School of Assassins"), leads the coup. The United States, under

Hillary Clinton's Department of State,

refuses to join international calls for the "immediate and

unconditional return" of Zelaya.

2017:

Honduras enters an electoral crisis as thousands of protesters

contest the results of the recent presidential election,

which many allege was rigged by the ruling party.

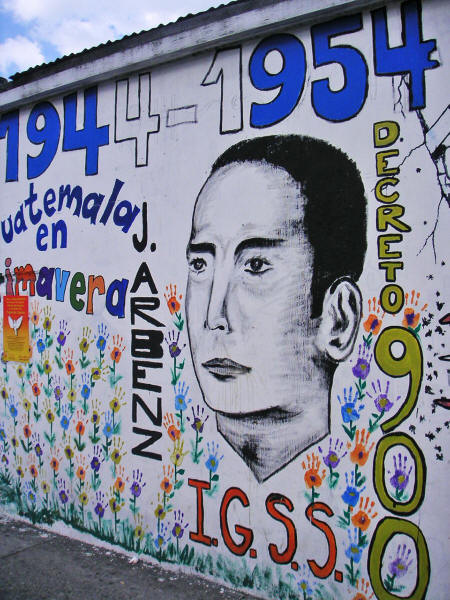

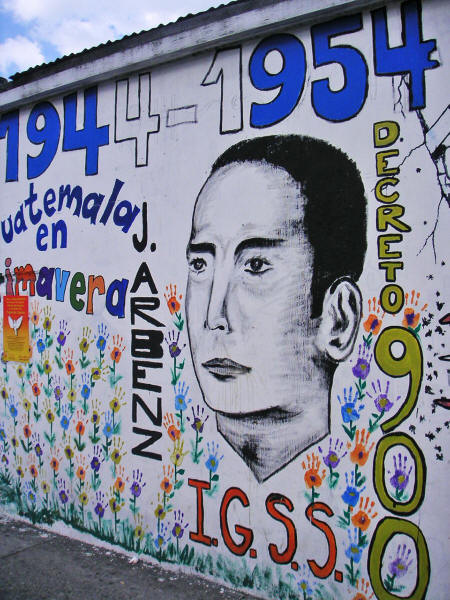

A present-day Guatemala City mural

memorializes deposed President Jacobo Árbenz

and his historic land reforms.

Credit: Soman via Wikimedia Commons

CC BY 2.5

1920:

President Manuel Estrada Cabrera, an ally to U.S. corporate

interests who had granted several concessions to the United

Fruit Company, is overthrown in a coup. The United States

sends an armed force to ensure the new president remains

amenable to U.S. corporate interests.

1947:

President Juan José Arévalo's self-proclaimed "worker's

government" enacts labor codes that

give Guatemalan workers the right to unionize and demand pay

raises for the first time. The United Fruit Company, as the

largest employer and landowner in the country, lobbies the U.S.

government for intervention.

1952:

Newly-elected President Jacobo Árbenz

issues the Agrarian Reform Law, which redistributes land to

500,000 landless - and largely indigenous - peasants.

1954:

Fearing the Guatemalan government's steps toward agrarian reform

and under the influence of United Fruit propagandist Edward

Bernays, President Eisenhower authorizes the CIA to

overthrow democratically elected President Jacobo Árbenz,

ending an unprecedented ten years of democratic rule in the

country, colloquially known as the "ten years of spring." In

Árbenz's place, the U.S.

installs Carlos Castillo Armas, whose authoritarian

government rolls back land reforms and cracks down on peasant

and workers' movements.

1965:

The CIA issues Green Berets and other counterinsurgency advisors

to aid the authoritarian government in its repression of

left-wing movements recruiting peasants in the name of "struggle

against the government and the landowners." State Department

counterinsurgency advisor Charles Maechling Jr. would later

describe the U.S.'s "direct complicity" in Guatemalan war

crimes, which he compared to the "methods of Heinrich Himmler's

extermination squads."

1971:

Amnesty International

finds that 7,000 civilian dissidents have been "disappeared"

under the government of U.S.-backed Carlos Arana, nicknamed "the

butcher of Zacapa" for his brutality.

1981:

The Guatemalan Army launches "Operation Ceniza" in response to a

growing Marxist guerrilla movement. In the name of

"counterattacks" and "retaliations" against guerrilla

activities, entire villages are bombed and looted, and their

residents executed, using high-grade military equipment received

from the United States. The Reagan administration

approves a $2 billion covert CIA program in Guatemala on top

of the shipment of $19.5 million worth of military helicopters

and $3.2 million worth of military jeeps and trucks to the

Guatemalan army. By the mid-1980s, 150,000 civilians are killed

in the war, with 250,000 refugees fleeing to Mexico. Military

leaders and government officials would later be tried for the

genocide of the Maya victims of military massacres.

1982:

A second U.S.-backed military coup installs Efraín Ríos Montt as

president. Montt is

convicted of genocide in 2013 for trying to exterminate the

indigenous Maya Ixil.

2006:

Ten years after a U.N.-brokered peace deal and the resumption of

democratic elections, Guatemala enters the CAFTA-DR free trade

deal with the United States. Ninety-five percent of U.S.

agricultural exports

enter Guatemala duty free.

|