|

by Tyler Durden

September 09, 2025

from

ZeroHedge Website

Source

On an autumn day in 2011, Jeffrey Epstein stepped into

JPMorgan Chase's headquarters at 270 Park Avenue and rode the

elevator to the executive floors where the bank's leaders, including

Chief Executive Jamie Dimon, kept their offices.

Epstein, who had pleaded guilty to a sex crime in

Florida three years earlier, had a message for the bank's top

lawyer, Stephen Cutler:

he had "turned over a new leaf," he said, and

powerful friends could vouch for him.

"Go talk to Bill Gates about

me"...

Key takeaways:

-

Epstein was connected to Israeli PM

Benjamin Netanyahu, not

just former PM Ehud Barak

-

He wired 'hundreds of millions of dollars

in payments to Russian banks and young Eastern European

women'

-

Accounts for young women were opened

without in-person verification (in one case a SSN could not

be confirmed)

-

Jes Staley was constantly running

interference for Epstein vs. JPM compliance concerns

-

Epstein had accounts at JPM for at least

134 (!) entities...

-

JPMorgan funded/serviced pieces tied to

Ghislaine Maxwell (millions, incl. $7.4M for a

Sikorsky helicopter) and helped finance MC2, the

modeling agency linked to

Jean-Luc Brunel.

For more than a decade, JPMorgan Chase processed

over $1 billion in transactions for Jeffrey Epstein, including,

hundreds of millions routed to Russian banks

and payments to young Eastern European women, opened at least

134 accounts tied to him and his associates, and even helped

move millions to Ghislaine Maxwell - including $7.4 million for

a Sikorsky helicopter - while anti-money laundering staff

repeatedly flagged large cash withdrawals and wire patterns

aligned with known trafficking indicators, according to a new

report from the NY Times following a six-year investigation that

involved "some 13,000 pages" of legal and financial records.

Funny how they sat on this until now - maybe it's

related to this, but do read on.

Illustration via FT

Inside JPMorgan, the debate over whether to keep Epstein as a client

had been simmering for years.

Epstein was lucrative.

His accounts held more than $200 million and

generated millions in fees, and he opened doors to wealthy prospects

and world leaders.

He had helped midwife the bank's 2004 purchase of

Highbridge Capital Management, earning a $15 million

payday.

Senior bankers credited him with introductions to

figures such as Sergey Brin and Benjamin Netanyahu.

Sure enough, just as more bank employees were

losing patience with Epstein in 2011, he began dangling more

goodies.

That March, to the pleasant surprise of

JPMorgan's investment bankers in Israel, they were granted an

audience with Netanyahu. The bankers informed Staley, who

forwarded their email to Epstein with a one-word message:

"Thanks." (The bank spokesman said

JPMorgan "neither needed nor sought Epstein's help for

meetings with any government leaders.")

And around that same time, Epstein presented

an opportunity that, like the Highbridge deal years

earlier, had the potential to be transformative.

This one involved

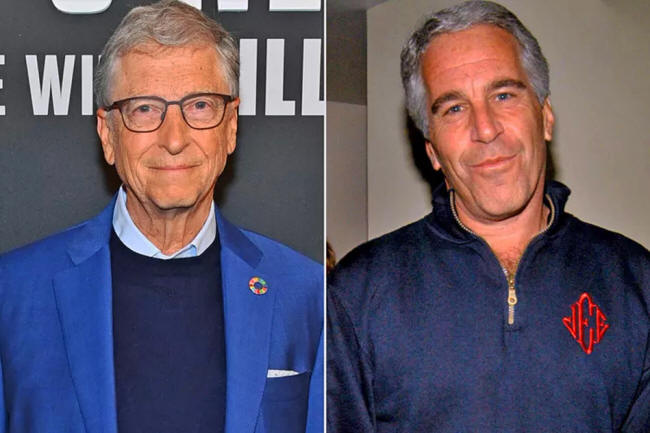

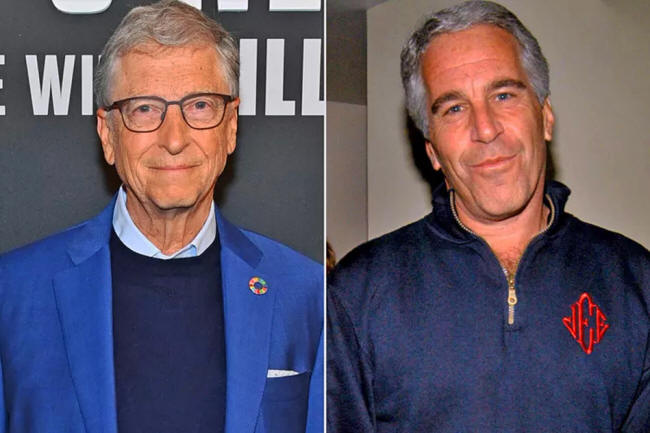

Bill Gates, who had only

recently entered Epstein's orbit...

Source

In an apparent effort to ingratiate - and

further entangle - himself with his bankers and the Microsoft

co-founder, Epstein pitched Erdoes and Staley on creating an

enormous investment and charitable fund with something like $100

billion in assets.

NY Times

Compliance leaders urged the bank to "exit" the

felon after anti-money laundering personnel flagged a yearslong

pattern of large cash withdrawals and constant wires that, in

hindsight, matched known indicators of trafficking and other illicit

conduct.

Instead, top executives overrode objections at

least four times, allowed accounts for young women to be opened with

scant verification, and paid Epstein directly - the aforementioned

$15 million tied to a hedge-fund deal and $9 million in a

settlement.

Even in 2011, as concerns mounted, internal notes

referenced decisions "pending Dimon review," while Jes Staley,

a senior executive and Epstein confidant, traded sexually suggestive

messages ("Say

hi to Snow White") and shared confidential bank

information with the client.

Exact dollar figures and destinations across years:

-

$1.7M in cash (2004–05) and earlier $175K

cash (2003).

-

$7.4M wired to buy Maxwell's Sikorsky

helicopter.

-

$50M credit line approved in 2010 even

post-plea; ~$212M then at the bank (about half his net

worth).

-

$176M moved to Deutsche Bank after the

2013 exit.

JPM of course regrets everything - calling their

relationship with Epstein,

"a mistake and in hindsight we regret it, but

we did not help him commit his heinous crimes," Joseph

Evangelisti, a JPMorgan spokesman, said in a statement.

"We would never have continued to do business

with him if we believed he was engaged in an ongoing sex

trafficking operation."

The bank has placed much of the blame on Jes

Staley, then a rising executive and close confidant of Epstein.

"We now know that trust was misplaced,"

Evangelisti said.

A Client too Valuable to Lose

Epstein's ties to JPMorgan reached back to the late 1990s, when

then-Chief Executive Sandy Warner met him at 60 Wall Street

and urged a lieutenant, Mr. Staley, to do the same.

Epstein soon became one of the private bank's

top revenue generators.

A 2003 internal report estimated his net

worth at $300 million and attributed more than $8 million in

fees to him that year.

Even then, there were warning signs. In 2003

alone, he withdrew more than $175,000 in cash.

Bank employees recognized the need to report

large cash transactions to federal monitors but failed to treat the

withdrawals as a signal of deeper risk.

In the years that followed, compliance staff

repeatedly expressed alarm over Epstein's wires, cash activity and

requests to open accounts for young women with minimal verification.

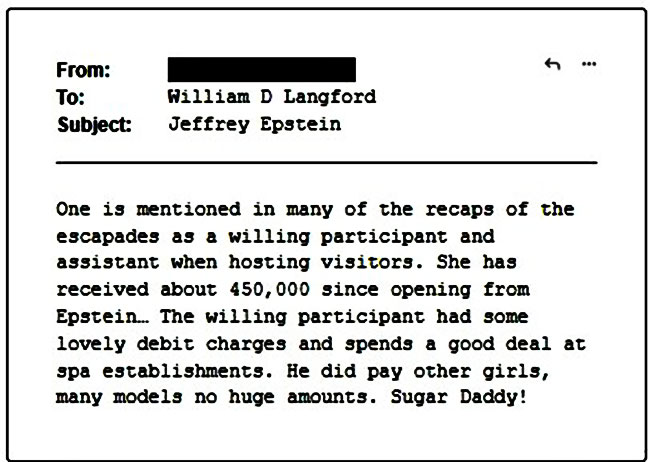

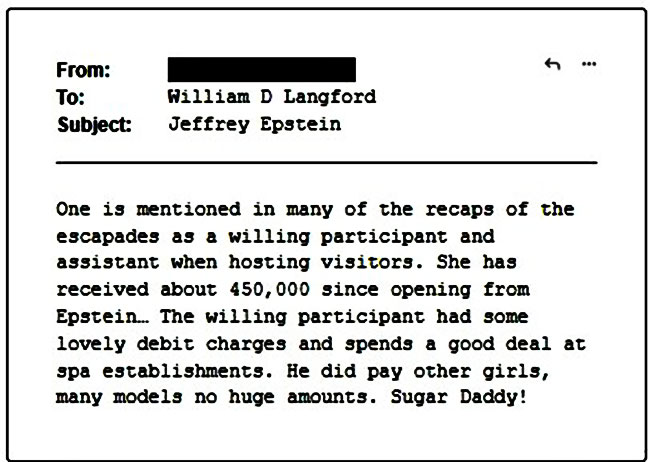

One internal note, describing large transfers to

an 18-year-old totaling,

"about 450,000 since opening," read: "Sugar

Daddy!"

Still, influence carried weight. Epstein was

prized not only for his personal balances but for the business he

brought in.

Through his network, which included hedge fund

founder Glenn Dubin and a constellation of billionaires and

officials, he introduced potential clients and helped shape the

bank's strategy.

The Highbridge deal was heralded

internally as,

"probably the most important transaction" of

Mr. Staley's career.

Internal Dissent, Repeatedly

Overruled

From 2005 to 2011, the bank's leaders revisited the Epstein question

several times.

In 2006, after a Florida indictment alleging

solicitation from a teenage girl, JPMorgan convened a team to decide

whether to exit the client. The bank swiftly jettisoned another

customer, the actor Wesley Snipes, when he faced tax charges.

It did not do the same with Epstein. Instead, it

imposed a narrow restriction - not to "proactively solicit" new

investments from him - while continuing to lend and move his money.

Within the bank, even casual exchanges betrayed an awareness of

Epstein's proclivities.

"So painful to read," Mary Erdoes, now

head of asset and wealth management, emailed upon seeing news of

the indictment.

Mr. Staley replied that he had met Epstein the

prior evening and that Epstein "adamantly denies" involvement with

minors.

At other moments, the tone turned flippant.

Describing a Hamptons fundraiser, Mr. Staley

wrote that the age gaps among couples,

"would have fit in well with Jeffrey," to

which Ms. Erdoes replied that people were "laughing about

Jeffrey."

By 2008, after Epstein pleaded guilty and

registered as a sex offender, pressure mounted to end the

relationship.

"No one wants him," one banker wrote.

Mr. Cutler, the general counsel, would later say

he viewed Epstein as a reputational threat:

"This is not an honorable person in any way.

He should not be a client."

Yet he did not insist on expulsion, and the

matter was not escalated to Mr. Dimon. Epstein remained.

In early 2011, William Langford, head of compliance and a

former Treasury official,

urged that Epstein be "exited."

He warned that ultrawealthy clients could warp

judgment and that patterns in Epstein's accounts resembled those of

trafficking networks.

The bank's head of compliance, William

Langford, was especially alarmed.

"No patience for this," he emailed a

colleague.

Langford had joined JPMorgan in 2006 after

years of policing financial crimes for the Treasury Department.

He knew - and had warned colleagues - that

companies can be criminally charged for money laundering if they

willfully ignored such activities by their clients.

He saw ultrawealthy customers as a particular

blind spot; all the time that private bankers spent wining and

dining these lucrative clients could cloud judgments about their

trustworthiness.

It looked like that was what was

happening with Epstein.

One of Langford's achievements at JPMorgan

was the creation of a task force devoted to combating

human trafficking.

The group noted in a presentation that

frequent large cash withdrawals and wire transfers - exactly

what employees were seeing in Epstein's accounts - were totems

of such illicit activity.

...

Langford said in a deposition that he started off by quickly

explaining the human-trafficking initiative. In that context,

how could the bank justify working with someone who had pleaded

guilty to a sex crime and was now under investigation for sex

trafficking?

NY Times

Mr. Staley pushed back, relaying Epstein's

insistence that allegations would be overturned.

Days later, the bank agreed to keep the accounts

open.

Money, Access

and a Second Chance

Even as internal skepticism grew, Epstein stayed in touch with his

former private banker, Justin Nelson, and continued to

surface in meetings involving Leon Black, a billionaire

client.

Staley remained close to Epstein for years,

exchanging personal messages and visiting his residences, even as he

ascended to run Barclays.

In 2019, after Epstein was arrested on federal

sex trafficking charges and later died by "suicide" in a Manhattan

jail, investigators, journalists and regulators turned anew to his

banking relationships.

JPMorgan launched an internal review, code-named Project Jeep,

and filed belated suspicious activity reports flagging about 4,700

Epstein transactions totaling more than $1.1 billion.

The bank settled civil claims with Epstein's

victims for $290 million and with the U.S. Virgin Islands for $75

million, without admitting wrongdoing.

No executives lost their jobs.

Mr.

Jamie Dimon, who testified

that,

he did not recall knowing about Epstein

before 2019,

...remains one of the most powerful figures in

American finance.

To

Bridgette Carr, a law professor

and anti-trafficking expert retained by the Virgin Islands, the case

poses a larger question about incentives.

JPMorgan, she concluded, enabled Epstein's

crimes.

"I am deeply worried here that the ultimate

message to other financial institutions is that they can keep

serving traffickers," she said.

"It's still profitable to do that, given the

lack of substantial consequences."

|