|

Artistís concept showing an Earth-like planet

orbiting a star that

has formed a stunning "planetary nebula."

Credit: David A. Aguilar (CfA)

8 Newfound Alien Worlds...

Could Potentially Support Life

by Mike Wall

January 06, 2015

from

Space Website

Astronomers have discovered eight

new exoplanets that may be capable

of supporting life as we know it, including what they say are the

two most Earthlike alien worlds yet found.

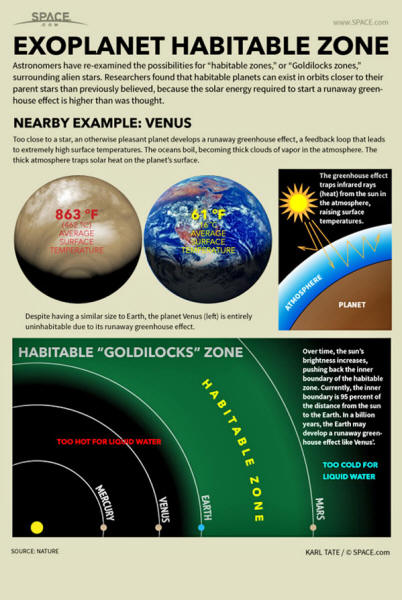

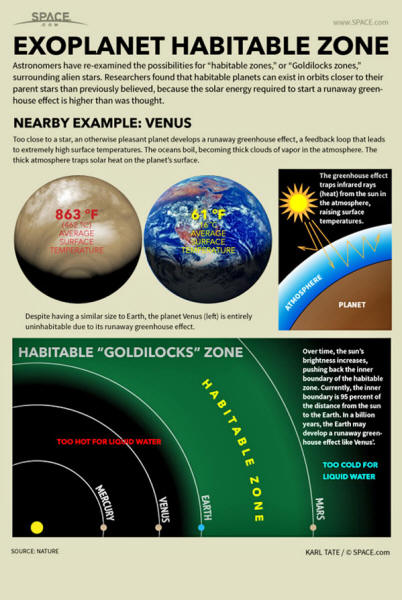

All eight newfound alien planets appear to orbit in their parent

stars' habitable zone - that just-right range of distances that may

allow liquid water to exist on a world's surface - and all of them

are relatively small, researchers said.

"Most of these planets have a good chance of being rocky, like

Earth," study lead author Guillermo Torres, of the

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), said in a

statement.

The haul doubles the number of known habitable-zone planets that are

potentially rocky, study team members said.

The newly discovered worlds were all detected by NASA's prolific

Kepler space telescope, then confirmed using observations by other

telescopes and a computer program that assessed the statistical

probability that they are bona fide planets (as opposed to false

positives).

While none of the eight is a true "alien Earth," two of them

- known

as

Kepler-438b and

Kepler-442b - stand out for their similarities to

our home planet (though both worlds orbit red dwarfs, stars that are

smaller and dimmer than Earth's sun).

Kepler-438b, which lies 470 light-years from our solar system, is

just 12 percent wider than Earth and has a 70 percent chance of

being rocky, study team members said.

The planet completes one orbit

every 35 days and receives about 40 percent more energy from its

star than Earth does from the sun.

Kepler-442b is about one-third larger than Earth, and has a 60

percent chance of being rocky. The exoplanet's orbital period is 112

days, and it gets about two-thirds as much energy as Earth,

scientists said. Kepler-442b is about 1,100 light-years from Earth.

As intriguing as these two worlds are, there's no guarantee that

either of them could actually host life, team members stressed.

"We don't know for sure whether any of the planets in our sample are

truly habitable," co-author David Kipping, also of the CfA,

said

in the same statement.

"All we can say is that they're

promising candidates."

Such hedging is unavoidable at this point, because researchers just

don't have enough information.

For starters, there's the uncertainty

about the planets' composition, as evidenced by the estimated

rockiness probabilities. (Nobody knows for sure where the dividing

line lies between rocky and gaseous worlds, in terms of planet

size.)

Furthermore, a planet's surface temperature is highly dependent on

the composition and thickness of its atmosphere, and nothing is

known about the air surrounding Kepler-438b, Kepler-442b or any of

the other newfound worlds.

And some scientists employ a more restrictive definition of

"habitable zone" than others. Indeed, study team member Douglas

Caldwell, who presented the results today (Jan. 6) at the annual

winter meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in

Seattle, said that only three of the newly confirmed planets are

"securely" in the

habitable zone:

But he's not discounting the life-hosting chances of the other five.

"All of these planets are small, all of them are potentially

habitable - and, in fact, have a more than a 50 percent chance of

being in the slightly extended habitable zone - and all are

interesting," Caldwell, who's based at

the SETI (Search for

Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute in Mountain View,

California, said during a AAS press briefing today.

Other big exoplanet news was announced today at the AAS meeting as

well - namely, that scientists have identified 554 new planet

candidates in the Kepler mission's database, bringing the number of

total Kepler candidates to 4,175.

Just over 1,000 alien planets identified as potential worlds by

Kepler have been officially confirmed to date, but it's likely that

around 90 percent will eventually be validated, mission team members

say.

Among the newly announced 554 candidates are eight that are small

(between 1 and 2 times as wide as Earth) and orbit in their stars'

habitable zones.

Six of these eight potential planets circle a sun-like star.

"These candidates represent the closest analogues to the Earth-sun

system found to date," Fergal Mullally of the Kepler Science Office

said during today's AAS news conference.

"This is what Kepler has

been looking for. We are now closer than we have ever been to

finding a twin for the Earth around another star."

The $600 million Kepler mission launched in March 2009 to determine

how common Earthlike planets are throughout the Milky Way galaxy.

A

glitch ended the spacecraft's original planet hunt in May 2013, but

researchers are still combing through Kepler's huge database. (The

554 new candidates were pulled from observations made between May

2009 and April 2013.)

And last year, Kepler embarked upon a new, two-year mission called

K2, during which the observatory is searching for planets in a more

limited fashion and is also studying supernova explosions, star

clusters and other cosmic objects and phenomena.

Kepler has discovered more than half of all known exoplanets.

The

total alien-planet tally currently hovers around 1,800; the number

differs slightly depending on which database is consulted.

1,000 Alien Planets!

-

NASA's Kepler Space Telescope Hits Big

Milestone -

by Mike Wall

January 07, 2015

from

LiveScience Website

An artist's illustration of NASA's Kepler space telescope

observing

alien planets in deep space using the transit method.

The space

observatory has discovered more than 1,000 alien planets

since its

launch in March 2009.

Credit: NASA Ames/ W Stenzel

NASA's

Kepler spacecraft has discovered its 1,000th alien planet,

further cementing the prolific exoplanet-hunting mission's status as

a space-science legend.

Kepler reached the milestone today (Jan. 6) with the announcement of

eight newly confirmed exoplanets, bringing the mission's current

alien world tally to 1,004.

Kepler has found more than half of all

known exoplanets to date, and the numbers will keep rolling in:

The

telescope has also spotted 3,200 additional planet candidates, and

about 90 percent of them should end up being confirmed, mission

scientists say.

Furthermore, a number of these future finds are likely to be small,

rocky worlds with temperate, relatively hospitable surface

conditions - in other worlds, planets a lot like Earth.

(In fact, at

least two of the newly confirmed eight Kepler planets - which were

announced in Seattle today during the annual winter meeting of the

American Astronomical Society - appear to meet that description,

mission team members said.)

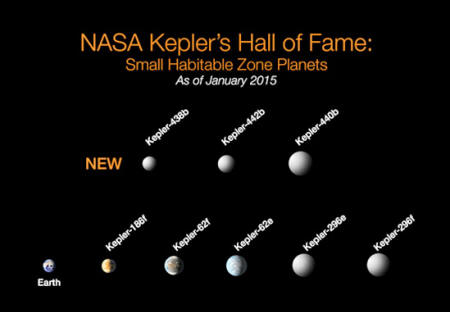

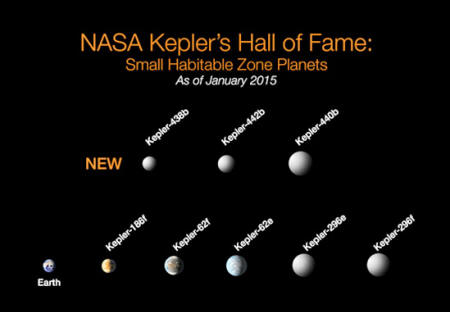

NASA's exoplanet-hunting Kepler space telescope

has

discovered more than 1,000 alien planets,

including the eight small,

potentially habitable worlds here.

Scientists announced Kepler's

1,000-planet milestone on Jan. 6, 2015.

Credit: NASA

"Kepler was designed to find these Earth analogues, and we always

knew that the most interesting results would come at the end,"

Kepler mission scientist Natalie Batalha, of NASA's Ames Research

Center in Moffett Field, California, told Space.com last month.

"So we're just kind of ramping up toward those most interesting

results," she added.

"There's still a lot of good science to come

out of Kepler."

Changing the game

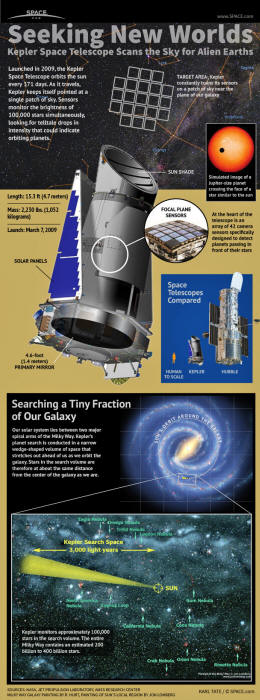

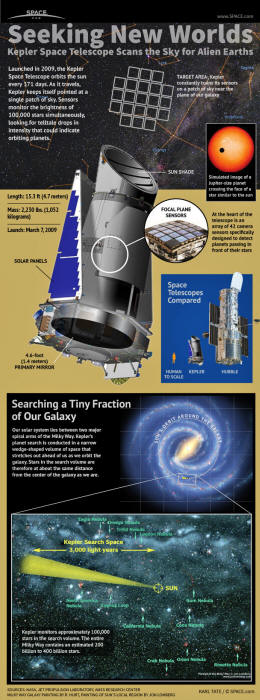

The mission of the Kepler Space Telescope

is to identify and

characterize Earth-size planets

in the 'habitable zones' of nearby

stars.

Credit: Karl Tate

SPACE.com contributor

Exoplanet science is a young field.

The first world beyond our solar

system wasn't confirmed until 1992, and astronomers first found

alien planets around a sun-like star in 1995.

The Kepler spacecraft has therefore been a revelation, and has

helped lead a revolution. The $600 million mission launched in March

2009, with the aim of determining how frequently Earth-like planets

occur around the Milky Way galaxy.

The telescope spots alien planets using the "transit method,"

watching for the telltale brightness dips caused when an orbiting

planet crosses the face of its host star from Kepler's perspective.

The instrument generally needs to observe multiple transits to flag

a planet candidate, which is part of the reason why the most

intriguing finds are expected to come relatively late in the

mission.

(Several transits of a huge, close-orbiting "hot Jupiter,"

which has no potential to host life, can be observed relatively

quickly, while it may take years to gather the required data for a

more distantly orbiting, possibly Earth-like world.)

"Before, we were just kind of plucking the low-hanging fruit, and

now we're getting down into the weeds, and things are getting a

little harder," Batalha said.

"But that's a challenge we knew we

would have."

Kepler candidates must then be confirmed

- by follow-up observations

using other instruments, for example, or by rigorous analysis of the Kepler dataset.

That enormous dataset has allowed researchers to study alien planets

in new systematic and statistical ways.

In 2013, for example, two

different studies used Kepler data to estimate the percentage of red

dwarfs - stars smaller and dimmer than the sun - that host

Earth-size planets in their "habitable zone" (the range of distances

from a star that could support the existence of liquid water).

One study put the number at 15 percent, while the other calculated

40 percent. Even the lower estimate should cheer astrobiologists,

for red dwarfs are the most common stars in the Milky Way, making up

about 70 percent of the galaxy's 100 billion or so stars.

Kepler has not yet discovered a true Earth twin - an Earth-size

planet in the habitable zone of a sunlike star - but the mission is

on track to figure out just how commonly these worlds occur

throughout the galaxy, Natalie Batalha said.

"I don't yet have a good sense of the completeness of the habitable

zone; it could be that we will be sensitive toward the inner half of

the habitable zone, maybe not the complete habitable zone," she

said.

"But I am confident now that we are going to get a number

based on actual discoveries, and that we are not going to have to

rely on extrapolation."

A new mission

Kepler's original planet-hunting campaign, which was designed to

last for 3.5 years, called for the spacecraft to continuously

monitor about 150,000 distant stars in the constellations

Lyra and

Cygnus.

The data-gathering part of that mission came to an end in May 2013,

when the second of Kepler's four orientation-maintaining reaction

wheels failed, robbing the spacecraft of its super-precise pointing

ability.

A repair mission is not going to happen; Kepler orbits the

sun, not the Earth.

But Kepler is still observing the heavens.

In May 2014, NASA

approved a new two-year

mission extension called K2 for the space

observatory, during which a compromised Kepler continues to hunt for

exoplanets but also observes other cosmic objects and phenomena,

including supernova explosions and star clusters.

K2 should spot a number of relatively nearby exoplanets that can be

observed in detail by NASA's $8.8 billion James Webb Space Telescope

(JWST), which is scheduled to launch in late 2018, Batalha said.

"So we will be well-poised when JWST launches to begin studying the

diversity of the atmospheres of planets, thanks to discoveries made

by K2," she said.

(NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or

TESS, scheduled to launch in 2017, should also find a number of

promising targets for follow-up work by JWST, researchers say.)

While K2 observations continue, Batalha and other Kepler scientists

are still busy analyzing data from the prime mission.

NASA wants

this work done by September 2017, and the team should meet that

deadline, Batalha said.

"Sometime around September of 2016, we'll probably have our final

catalog," she said.

"And then between September and January [of

2017], we'll be producing the products that will allow people to do

the statistics with the catalog. And then we'll kind of write up all

of our documentation and final papers, and turn off the lights and

go home sometime around the end of summer 2017."

But that moment won't mark the end of Kepler's contributions; NASA

could extend K2 for another two years, for example.

And even if the

spacecraft shuts its sensitive eyes in 2016, its observations will

keep researchers busy for a long time to come.

"I fully expect that scientists will be working through Kepler data

- and characterizing those planets and inferring various properties

of exoplanets based on that data - literally for decades," Batalha

said.

|