|

20 April 2015 from CosmosMagazine website

during its planned encounter with Pluto and its largest moon, Charon.

Credit:

NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest

Research Institute

Some scientists are convinced more planets exist in our Solar System.

But now, with NASA's New Horizons spacecraft three months away from giving us our first close-up view of Pluto, astronomers are beginning to wonder. The more we study the dwarf planet and its surrounds, the less lonely it appears.

Are there as-yet undiscovered worlds on

the far edge of the Solar System?

All are in a distant region of the Solar

System known as the Kuiper Belt.

Stern argues that Pluto itself provides

the biggest clue that other larger bodies are out there.

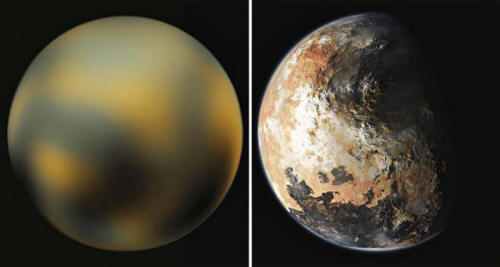

Left: A photomap of an image based on pictures of Pluto from 2002 to 2003 taken by the Hubble telescope. Right: an artist's impression of what Pluto may look like up close. Credit: NASA

In 2005 astrophysicist Robin Canup, also at the Boulder institute, published a study in Science that used computer simulations to show that early in Solar System history, Charon had been an independent world.

She calculated that it was captured by Pluto when the two collided.

Although the collision was not violent

enough to shatter either one, it slowed Charon so much that it was

unable to escape Pluto's gravitational grasp. Canup's model remains

the prevailing explanation for why Pluto has such a large moon.

Stern has calculated it would take 10,000 times the age of the entire Universe for any collision between a lonely Pluto and Charon to become likely.

But if you had "1,000 Pluto-sized objects" in the region, then the meeting becomes more probable said Stern at a meeting last year of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

Other scientists agree. One is Carlos de la Fuente Marcos, an astrophysicist at the University of Madrid, Spain.

In a pair of 2014 studies in the

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomy Society, his team looked

at the orbits of the 13 "extreme trans-Neptunian objects"

(planetoids whose orbits carry them at least five times farther out

than Neptune, or three times farther than Pluto's greatest distance

from the Sun).

Similarities in their orbits suggest they may have been shepherded into their current paths by gravitational interactions with much larger bodies.

is markedly different from those of other planets, which follow nearly circular orbits. Pluto's elliptical path means a small region of its orbit lies nearer the Sun than Neptune's (small blue dot).

Credit: Lookang /

Wikipedia

He says not yet published calculations

suggest these planets might be "super Earths", two to 15 times

more massive than our own planet.

But when it comes to understanding the orbits of these far-distant bodies, he says,

|