|

from Space Website

sold out in just 3 minutes online, host Neil deGrasse Tyson told the audience.

The debate featured

five experts chewing on the idea of the universe as a simulation.

Is the universe just an enormous,

fantastically complex simulation? If so, how could we find out, and

what would that knowledge mean for humanity?

The event honors Asimov, the visionary

science-fiction writer, by inviting experts in diverse fields to

discuss pressing questions on the scientific frontiers. Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of the museum's Hayden Planetarium and host of this year's event, invited five intellectuals to the stage to share their unique perspectives on the problem:

How can we tell?

Humanity might never be able to prove with certainty whether the universe is simulated, David Chalmers said.

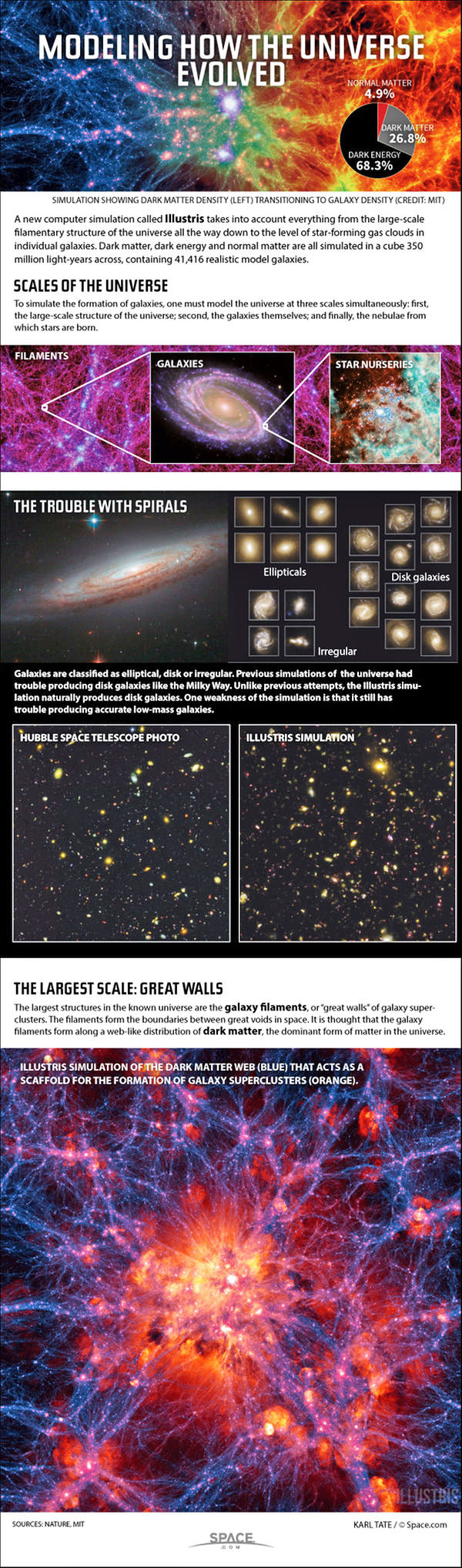

But other panelists said that, if the simulated universe has similar physical limitations to our perceived real universe - in which something infinitely complicated cannot be modeled without infinite resources - signs of shortcuts and approximations may lurk in our own world, the way an image breaks up into its constituent pixels when you get close enough to a screen.

Zohreh Davoudi proposed a possible way to spot one of these shortcuts: by studying cosmic rays, the most energetic particles scientists have ever observed. Cosmic rays would appear subtly different if space-time were formed of tiny, discrete chunks - like those computer pixels - as opposed to continuous, intact swaths, she said.

For the universe to be simulated in this way, it would have to be computed - meaning it would essentially be mathematical.

Max Tegmark's recent book, "Our Mathematical Universe - My Quest for the Ultimate Nature of Reality", focuses on why the universe seems so closely tied to math.

If he were a character in a video game or simulation, he'd begin to realize that the rules were rigid and mathematical in just that way, Tegmark said.

While Davoudi proposed searching for concrete evidence of computation in nature, James Gates, a physicist who works on superstring theory (an effort to describe all the universe's particles and forces with equations involving tiny, vibrating super-symmetric strings), has found something suspiciously like computation in the theoretical equations that govern how the universe works.

He discovered what looked like error-correcting codes, which are used to check for and correct errors that have been introduced through the physical process of computing.

Finding that type of code in a universe that is not computed is "extremely unlikely," Gates said.

But Randall noted that a universe in which errors were able to spread would quickly break down. So isn't it logical, she said, that the stable universe we find ourselves in could incorporate that type of feedback?

The researchers pointed out that a similar error-correction process works during the replication of DNA; organisms whose genetic material got too mangled would not survive.

Kinds of simulation

The debate also probed different possible simulations and the effects they'd have on our world.

For example, Tegmark discussed a famous "world as simulation" argument by philosopher Nick Bostrom:

But the argument strikes Tegmark as flawed.

For one, he asked,

A universe simulating ours used different physics than those in our universe, or contained an active being changing the simulation as it went (rather than being a universe run from first principles, as in the simulations Davoudi builds), the question would become,

In other words, it would be like Tegmark's video game character trying to understand the operating system his game runs on.

Chalmers added that, if the simulation were perfect, it'd be impossible to get information about the world outside. Only if it were buggy, or interactive, would we be able to find out anything about it.

But he'd "refuse to worship" the simulation's creator, regardless of its origin, Chalmers said.

Gates pointed out that such a simulation would mean reincarnation was possible - the simulation could always be run again, bringing everybody back to life.

What it would mean

When pressed, most of the researchers gave their predictions on how likely the world-as-simulation scenario was.

Davoudi wouldn't guess, Tegmark said it was 17 percent likely, Gates said there was just a 1 percent chance, Randall said effectively zero and Chalmers said 42 percent. (These estimates reflected a slightly higher likelihood than the guesses they gave just before the debate.)

Tyson likened understanding the universe to trying to figure out the rules of a chess game by just watching the pieces, as originally described by famed physicist Richard Feynman.

The question of the universe as a simulation might be more fundamentally about the extent humans can understand their universe from the inside out - that goal is much more essential than getting to the bottom of the simulation question, the researchers agreed.

Thinking about the world as a simulation is only useful in that it suggests interesting ways to explore the world scientifically, or encourages scientists to further hone their observational skills, she added.

|