|

from CNET Website

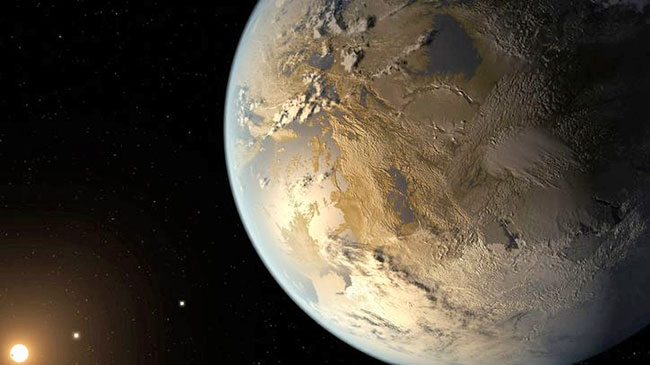

The potential number of Earth-like planets has suddenly exploded. Niels Bohr Institute University of Copenhagen

that the Milky Way alone is flush with billions of potentially habitable planets ...and that's just one sliver of the universe.

The research calculates that in our galaxy alone, there could be billions of planets hosting liquid water, habitable conditions and 'perhaps' even life.

The team predicted a total of 228 planets in the 151 planetary systems and then made a priority list with 77 planets in 40 planetary systems that are likely the easiest to observe with Kepler.

Digging deeper into the data, the researchers looked at how many planets were likely to be in the habitable zone where conditions to support liquid water and life might exist.

They found an average of one to three planets in the habitable zone in each planetary system.

Extrapolate those calculations further, and you arrive at the conclusion that if the math holds, there may be billions of habitable planets in the Milky Way, which is itself just one of billions of galaxies.

Kepler-186f - Click above image for more...

Should these calculations hold up - and the researchers behind them encourage astronomers to check to see whether the planets they predict are actually there to help bolster their case - it means that the chances of our planet being the universe's only potentially habitable rock that actually hosts life would be not one in a million, one in a billion or even one in a trillion - but one in a sextillion...

(In case this is your first time seeing that word, a sextillion is a one with 21 zeroes behind it.)

Actually, if the estimates of 40 billion Earth-sized planets in habitable zones of sun-like or red dwarf stars in the Milky Way and the estimate of the 100 billion to 200 billion galaxies in the universe are accurate - and if the average galaxy has roughly the same number of Earth cousins as the Milky Way, then the chances that we are the only planet with life are more like one in 6 sextillion.

To offer a frame of reference for that number, consider the amount of sand on Earth's beaches.

Jason Marshall, aka "The Math Dude," has calculated that there are roughly 5 sextillion grains of sand on all our planet's beaches combined.

So take every grain of sand on every beach on Earth and you can begin to be able to actually visualize how many planets we're talking about. Then you begin to wonder why we aren't overrun with aliens.

The apparent 'absence' of aliens then is probably due to the whole problem of figuring out interstellar travel.

To really understand the universe, you have to imagine a single beach containing all the sand from all our beaches, but then add the wrinkle that each grain of sand is separated from its nearest neighbor grain of sand on this beach by at least several trillions of miles.

While that's not a distance we can really comprehend, at least it's a number we've heard of. Maybe all this cosmic math isn't so boring after all.

It's significant in its ability to quantify our comparative insignificance...

|