|

by Richard A. Lovett

04

October 2019

from

CosmosMagazine Website

Italian version

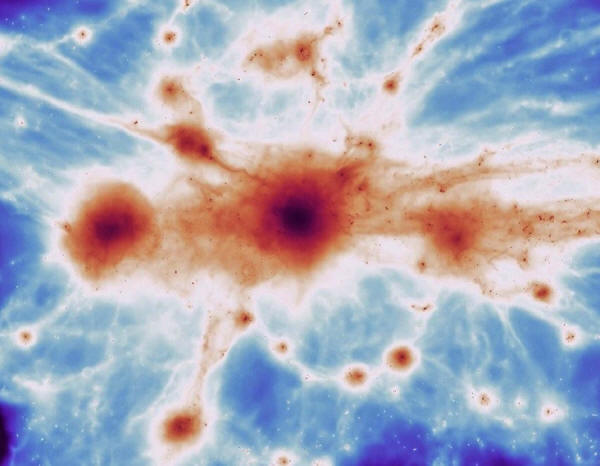

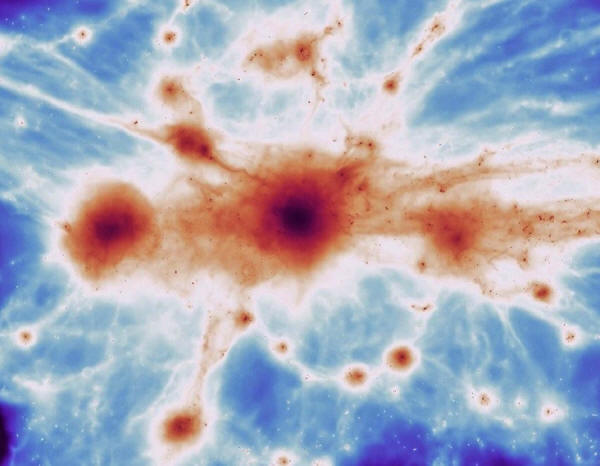

This image shows filaments

in a

massive galaxy cluster

using

the C-EAGLE simulation.

Joshua Borrow using C-EAGLE

Astronomers have

confirmed it

by viewing gas

billions of

light years away...

Faintly glowing wisps of gas surrounding galaxies 12 billion

light-years away have given astronomers their first chance to

confirm the existence of a structure known as 'the cosmic web.'

The web is a cobweb of gas filaments, which the standard

model of cosmology predicts would have formed in the aftermath of

the Big Bang.

Where these giant

filaments cross, the theory goes, is where galaxies form.

Hints that such filaments might exist, says Erika Hamden, an

astrophysicist at the University of Arizona, Tucson, had previously

shown up in the spectra of distant galaxies, which contained

absorption bands indicating that the light from them had passed

through large hydrogen clouds en route to Earth.

"So you can tell

there's a bunch of hydrogen between you and the galaxies," she

says.

But whether that meant

the light had passed through one or more of the cosmic web's

filaments, or something else, was unclear.

In a paper (Gas

Filaments of the Cosmic Web located around Active Galaxies in a

Protocluster) published in the journal Science, however,

a team led by Hideki Umehata, an astronomer at the

RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering

Research, Japan, used one of the Earth's largest telescopes to

look at a massive protogalaxy known as

SSA22, 12 billion light-years away

in the direction of the

constellation Aquarius.

That's far enough away that the light from it had been traveling

toward us for most of the history of the Universe... meaning that

Umehata's team was peering back in time to only 1.8 billion years

after the Big Bang.

Umehata's team then ran the light through a spectroscope to look for

the glow of hydrogen illuminated by high-energy radiation from

nearby galaxies.

These galaxies "kind

of act like flashlights," explains Hamden, whose own paper (Observing

the Cosmic Web) commenting on Umehata's appears in

the same issue.

Detection was made

possible, she adds, by a spectrographic instrument called the

Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE):

a high-resolution

spectrograph that allows astronomers to look for spectroscopic

signatures of things like hydrogen, over a wide field of view.

"That is the only

reason it could be done," Hamden says, "because these

structures are so big that you need a big field of view...

to see them."

It's an important result,

she adds, because the cosmic web is one of the key predictions of

the standard model of cosmology.

Finding a piece of it,

"is an indicator that

we're on the right track".

It's also important, she

says, because astronomers have long believed that most of the normal

matter in the Universe isn't in galaxies.

Proving that the web

exists is therefore an important step in figuring out where it does

lie. The next step, according to Umehata, is to look for more

filaments.

So far, he says,

"We just opened a

small window. The cosmic web should be much larger."

Also, he adds,

"it would

be useful to search for elements other than hydrogen, such as

helium or carbon, and to look for older filaments

closer to the Earth."

"It would be exciting

to see the evolution of filaments, and galaxy formation within

filaments, across cosmic time."

|