|

|

|

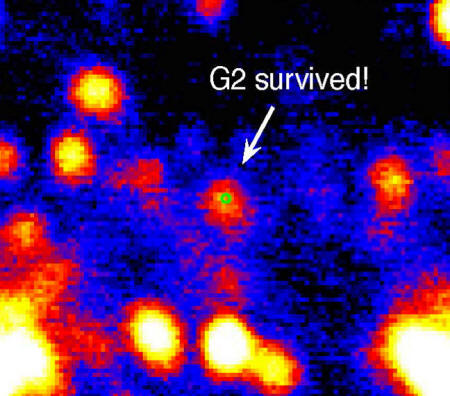

Astronomers watched in fascination as an object called G2 appeared to edge closer to our Milky Way's central black hole.

But G2 survived!

In 2011, astronomers said they'd discovered a cloud of gas - with several times Earth's mass - accelerating fast towards the supermassive black hole at the center of our Milky Way.

The cloud appeared to be undergoing spaghettification - sometimes called the noodle effect - stretching and elongating as it neared the black hole. It was thought at first the cloud - which came to be called G2 - would meet a fiery end as it passed into the Milky Way's black hole as early as 2013.

It did not, but astronomers now say it passed closest to the hole in northern summer of 2014. Unexpectedly, however, our galaxy's black hole did not swallow it. Instead, G2 survived!

This week (November 3, 2014), UCLA astronomers published a new paper (Detection of Galactic Center Source G2 at 3.8 Microns during Periapse Passage) in the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters offering a new explanation as to what G2 is and how it survived its black hole passage.

Andrea Ghez, UCLA professor of physics and astronomy, said in a press release:

Ghez' team now suggests that G2 is a pair of binary stars that had been orbiting the black hole in tandem and merged together into an extremely large star. This merger may have been cloaked in gas and dust, and choreographed by the object's proximity to the black hole's powerful gravitational field.

Ghez said:

Ghez noted that massive stars in our galaxy primarily come in pairs.

When the two stars merge into one, the star expands for more than one million years, Ghez said,

G2, on the other hand, would be in its expansive stage now.

It appears to have an unusual, 300-year elliptical orbit around the black hole.

Bottom line:

Astronomers watched in fascination as an object called G2 - apparently a gas cloud - appeared to edge closer and closer to our Milky Way's central black hole.

But G2 survived!

Now, instead of a gas cloud, astronomers believe G2 is a binary star system, that is, two that had been orbiting the black hole in tandem and merged together into an extremely large star.

...Near Black Hole Identified

Keck Observatory is a private 501(c) 3 non-profit organization and a scientific partnership of the California Institute of Technology, the University of California and NASA.

Credit: Andrea Ghez, Gunther Witzel/UCLA Galactic Center Group/W. M. Keck Observatory

Credit: Ethan Tweedie Photography

MAUNA KEA, Hawaii

The mystery about a thin, bizarre object in the center of the Milky Way headed toward our galaxy's enormous black hole has been solved by UCLA astronomers using the W.M. Keck Observatory, home of the two largest telescopes on Earth.

The scientists studied the object, known as G2, during its closest approach to the black hole this summer, and found the black hole did not dine on it.

The research is published today in the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters (Detection of Galactic Center Source G2 at 3.8 Microns during Periapse Passage).

While some scientists believed the object was a cloud of hydrogen gas that would be torn apart in a fiery show, Andrea Ghez and her team proved it was much more interesting.

Instead, the team has demonstrated it is a pair of binary stars that had been orbiting the black hole in tandem and merged together into an extremely large star, cloaked in gas and dust, and choreographed by the black hole's powerful gravitational field.

Ghez and her colleagues - who include lead author Gunther Witzel, a UCLA postdoctoral scholar in Ghez's research group, and Mark Morris, a UCLA professor of physics and astronomy - studied the event with both of the 10-meter telescopes at Keck Observatory.

Keck Observatory employs a powerful technology called adaptive optics, which Ghez helped to pioneer, to correct the distorting effects of the Earth's atmosphere in real time, and to reveal the region of space around the black hole.

With adaptive optics, Ghez and her colleagues have revealed many surprises about the environments surrounding supermassive black holes, discovering, for example, young stars where none were expected and seeing a lack of old stars where many were anticipated.

The researchers wouldn't have been able to arrive at their conclusions without the Keck's advanced technology.

Massive stars in our galaxy, she noted, primarily come in pairs.

When the two stars merge into one, the star expands for more than one million years, "before it settles back down," Ghez said.

G2, in that explosive stage now, has been an object of fascination.

G2 makes an unusual, 300-year elliptical orbit around the black hole and Ghez's group calculated its closest approach occurred this summer - later than other astronomers believed - and they were in place at Keck Observatory to gather the data.

Black holes, which form out of the collapse of matter, have such high density that nothing can escape their gravitational pull, not even light. They cannot be seen directly, but their influence on nearby stars is visible and provides a signature, said Ghez, a 2008 MacArthur Fellow.

The W.M. Keck Observatory operates the largest, most scientifically productive telescopes on Earth.

The two, 10-meter optical/infrared telescopes near the summit of Mauna Kea on the Island of Hawaii feature a suite of advanced instruments including imagers, multi-object spectrographs, high-resolution spectrographs, integral-field spectographs and world-leading laser guide star adaptive optics systems.

NIRC2 (the Near-Infrared Camera, second generation) works in combination with the Keck II adaptive optics system to obtain very sharp images at near-infrared wavelengths, achieving spatial resolutions comparable to or better than those achieved by the Hubble Space Telescope at optical wavelengths.

NIRC2 is probably best known for helping to provide definitive proof of a central massive black hole at the center of our galaxy.

Astronomers also use NIRC2 to map surface features of solar system bodies, detect planets orbiting other stars, and study detailed morphology of distant galaxies.

|