|

from

Space Website

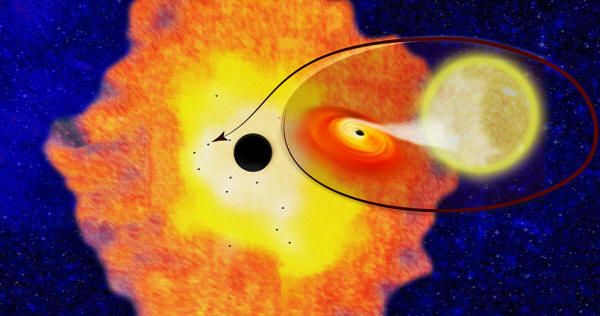

is surrounded by a swarm of smaller black holes, according to new research. Scientists were able to pinpoint at least 12 black hole binaries,

where a

black hole is siphoning material from a companion star.

A swarm of thousands of black holes may surround the giant black hole at the heart of our galaxy, a new study finds.

At the hearts of most, if not all, galaxies are supermassive black holes with masses that are millions to billions of times that of the sun. For example, at the center of our galaxy, the Milky Way, lies Sagittarius A*, which is about 4.5 million solar masses in size.

A key way in which scientists think supermassive black holes grow is by engulfing stellar-mass black holes each equal in mass to a few suns.

Learning how that growth process works is vital to understanding the effects they can have on the evolution of their galaxies.

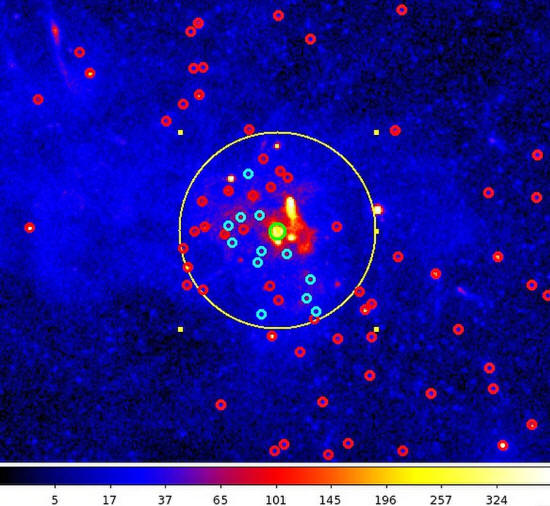

A view of Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way, taken with the Chandra X-ray Observatory (circled in green). The black hole is visible as a bright spot because it is emitting some of its occasional X-ray flares. Surrounding it are other X-ray sources

caused by binary systems with smaller black holes.

For decades, astronomers have looked for up to 20,000 black holes that previous research predicted should be concentrated around the Milky Way's core.

Sagittarius A* is surrounded by a halo of gas and dust that provides the perfect breeding ground for massive stars, which can then give rise to black holes after they die, said study lead author Chuck Hailey, co-director of the astrophysics lab at Columbia University in New York.

In addition, the powerful gravitational pull of Sagittarius A* can pull in black holes from outside this halo, he added.

However, until now, researchers failed to detect such a heavy concentration of black holes, called a "density cusp."

Black holes absorb anything that falls into them, including light (hence, their name), making them difficult to spot against the dark background of space.

Instead, to detect black holes, scientists generally look for ones with nearby companion stars.

In such binary systems, the black hole may be tearing apart its partner, giving off radiation in the process.

In the past, failed attempts to find the density cusp focused on looking for strong bursts of X-rays that are thought to come from instabilities in so-called "accretion disks" of gas and dust that spiral off from companion stars into black hole partners.

However, the galactic center is about 26,000 light-years from Earth, and,

Instead, Hailey and his colleagues looked for the steadier, less-energetic X-rays given off by accretion disks when the binaries are relatively inactive.

Using archival data from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, they detected a dozen such X-ray binaries within about one parsec, or about 3.26 light-years, from the galactic core, findings they detailed in the April 5 issue of the journal Nature.

By analyzing the properties and spatial distribution of these X-ray binaries, the researchers extrapolated that 300 to 500 X-ray binaries may lurk in the core of the Milky Way, and about 10,000 isolated black holes without companion stars may also lurk there.

These findings may also,

However, the researchers cautioned that making estimates regarding the number of black holes in the galactic core is complicated by the fact that there are likely other sources of X-rays from the center of the galaxy, such as pulsars.

Future X-ray observatories may be able to distinguish these different kinds of X-ray sources, Hailey said.

|