|

from

WeirdLord Website

Men never do evil so

completely and cheerfully as

when they do it from religious conviction.

- Blaise

Pascal (1623-1662)

THE RECENTLY deceased pontiff, Pope John

Paul II, left a decidedly mixed legacy.

While he deserves great credit for

helping prevent the fall of the Soviet Union detonate into the kind

of revolutionary bloodbath that history so often records with that

profound of a change of government, even that is not without a dark

side.

For it can be argued that the policy's

success against the atheistic regime in the West led to the

employment of religious fanatics in Afghanistan, which ironically

means that Pope John Paul's success in Poland led directly to al-Queda,

Osama, and ultimately,

September 11.

Also, John Paul II has been roundly criticized by his

supporters like the late

Malachi Martin for allowing the

Roman Church to stagnate and ossify, even as the pope himself did.

Indeed, not content with such actions

like rewarding the disgraced prelate and clergy-abuse cover-up king

of Boston, Cardinal Bernard Law, he has also been accused of

aiding in the cover-up by refusing to investigate the prominent head

of the Legionaries of Christ.

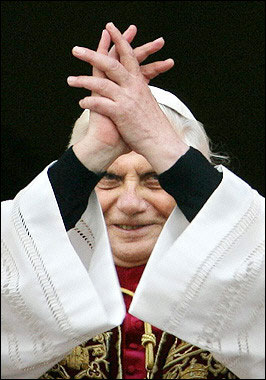

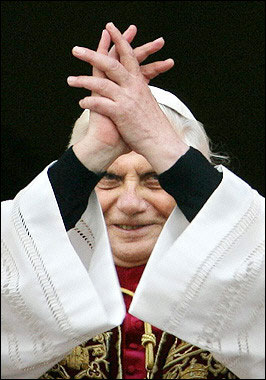

Pope Benedict XVI,

former head of the

Inquisition

In the latter years of his reign, the Holy Office of the

Inquisition, now called the Sacred Congregation for the

Propagation of the Faith, was headed by orthodoxy-czar Cardinal

Josef Ratzinger, now Pope Benedict XVI.

It once again became responsible for

dealing with the worldwide clergy abuse scandal, for John Paul

transferred all those cases involving desecrating the Eucharist or

buggering altar boys back to its jurisdiction once again. It still

ferrets out errant priests, but until the recent round of crises,

its chief interests seemed to be seeking out the theologically

treacherous ones. For those who threaten the faith have always been

considered a graver menace than those who endanger the bodies of

believers.

It will be very interesting to see whether the new pontiff will use

his power to silence dissenters or oust abusers. Yet the signs are

not good. It was recently reported that in 2001, then-Cardinal

Ratzinger signed a letter sent to all bishops, asserting the

Church's right to hold secret inquiries and keep the evidence

confidential for 10 years after the victims reached adulthood under

pain of excommunication. This continued the policy of secrecy

confirmed by "good" Pope John XXIII in the secret instructions on

Crimes of Solicitation.

Despite the hopeful spin in the press accompanying the start of his

reign, the outlook is very grim under Benedict XVI.

Rectifying

history

In any case, back in 1998, Pope John Paul II resolved to set

the record straight on that most troublesome black mark on the

Catholic Church's permanent record, the Inquisition.

Thus, he

summoned a group of 50 tame scholars, let them peek into the depths

of the Vatican Secret Archives, and issue a report of nearly 800

pages.

In 2000, perhaps fearful of Christ returning unexpectedly or due to

his own failing health, the pope went ahead and apologized for

"errors committed in the service of the truth through recourse to

non-evangelical methods." He even went so far as to "rehabilitate"

Galileo, although fudging like a diocesan lawyer might not

have been the best way to show his deep, sincere feelings.

Not surprisingly, the experts' learned verdict was that the poor

Inquisition had been sadly misjudged. The report found, for example,

that there had been trials of some 125,000 suspected heretics in

Spain, only 1% (a mere 1,250) had been executed. And in Portugal,

only 5.7% of the 13,000 tried had been condemned. It wasn't anywhere

near as bad as everyone had always said; and anyway the Church

didn't burn all those people, the State did. (AP, 6/15/04)

What a load of rubbish!

The Inquisition was simply the

most diabolical institution ever created by humanity, and the

state was for the most part merely its tool. For the pope to demur

on the depths of the Inquisition's evil is like the chancellor of

Germany refusing to condemn the Holocaust. Both are great,

unspeakably horrible spiritual scars on humanity's collective soul

whose wickedness cannot be fully comprehended.

The Inquisition might arguably be considered an even worse evil than

the Holocaust.

Though the number of victims of the

latter was higher, without the Inquisition's example of deliberate,

bureaucratic oppression, the Holocaust would not have been so easily

imaginable. Not just in its grandiose intent and direct tactics such

as the use of spies and parish registers but even in the some of the

most minor details.

For instance, yellow tunics called

sanbenitos that the Inquisition made some penitents publicly

wear inspired the yellow stars of David that Jews were forced to

don in the ghettoes, as well as the colored triangles that

distinguished the various categories of inmates in the camps.

With the blessing of

a Spanish inquisitor, familiars haul the condemned,

garbed in paper

miters and sanbenitos, into a "slow oven" to be roasted alive.

This shows that not only was the

Inquisition a monstrous evil in and of itself, it has left a

legacy of horror that is unmatched.

All the repressive systems of whatever

flavor that have ever been imposed on the suffering masses of the

world have owed their inspiration to the Holy Office of the

Inquisition.

The Nazi Gestapo and secret police everywhere, including the

Soviets, Saddam and the Shah, CIA mind-control experiments,

McCarthy's Red Scare, Mao's Red Guards, the Khmer Rouge, certain

aspects of the War on Drugs and the shameful abuse and torture of

prisoners at Abu Ghraib, Gitmo, and elsewhere, all utilized

techniques pioneered by those most devoted servants of Holy

Mother Church.

The SS and the CIA have both undoubtedly

studied the old manuals with care, and for good reason.

The Inquisition perfected the use of all

kinds of torture, psychological assaults and humiliation, secret

proceedings, anonymous accusations, indefinite detentions, spies and

informers, and the confiscation of property.

The mechanisms

of repression

The Inquisition took several forms, chiefly papally-run in the

medieval period, and much more an instrument of political oppression

in its later Roman and Spanish incarnations. But in one guise or

another, it terrorized large sections of Europe for well over half a

millennium.

Threatening rich and poor alike, cleric

and lay; kings and bishops fell under its scrutiny equally as

wandering clerics and errant knights. Mighty lords, even entire

religious orders approved by the pope like the

Knights Templar, could be summoned

at any time and crushed without mercy for suspicions of which they

would not be told. Nor could they resist.

Perhaps it was inevitable in a religion that placed such emphasis on

the torture and execution suffered by its founder.

Jesus, too, had

been arrested by the religious authorities for heresy and then

killed by the civil rulers for rebellion. For hundreds of years

thereafter, Christianity had been ruthlessly oppressed by the Roman

Empire. Many missionaries had died horribly converting the invading

barbarians later as well. Finally, after a prolonged effort of

centuries, the continent had been baptized into a common faith.

Christianity began to remake Europe in

its own image.

-

Was the Inquisition, then, some

sort of revenge for the ages of persecution?

-

Was it a form of psychological

repetition of the trauma?

-

Did the omnipresent depictions

of the crucifixion used everywhere in the Latin Church, the

constant emphasis on the betrayal and murder of Christ

lead to some sort of psychological need to re-enact it

repeatedly?

-

Did the fear of hell make them

create a real one on Earth?

Like the thirst for red martyrdom in the

early Church, or the recent biblical gore-fest, The Passion of

the Christ, there is an unhealthy and morbid sadism

somehow involved.

In any case, the Inquisition was an iron reign of terror like none

ever before. It marked the triumph of papal politics but also the

fatal weakness that was hidden at its very heart: the fact that the

pope's power depended solely on the consent of the faithful.

The medieval Inquisition came into being by 1233, at the behest of

Pope Gregory IX, the violent culmination of a long process of

confronting heresy. Under his predecessor, the imperial Pope

Innocent III, the papacy had recently attained a temporary supremacy

of sorts over the German emperors and other secular powers who had

often, in the pope's view, flirted with heresy by doing totally

unacceptable things like choosing their own bishops.

Innocent did his best to make sure that

Rome would stay on top by creating the canonical and organizational

groundwork for an international strike force of trusted agents that

could go anywhere to drag anyone off to their secret detention

centers where they could use any means necessary to extract the

truth. (Sound familiar?)

Such extreme measures were needed, it was universally believed,

because of the rise of heresy. As the Church became richer in the

Middle Ages, corruption grew, and the old standards of piety and

ascetic purity declined. Many reformers sought to reverse this by

appealing past the intermediacy of the Church directly to the Gospel

and its emphasis on the poor.

Some even organized their followers into

orders.

A fortunate few, like Francis of Assisi,

obtained a sympathetic hearing and approval. While some of his

followers went on to become heretics when they denied the Church's

right to property, others were co-opted by that same Church to serve

as persecutors. Some would-be reformers, like Peter Waldo of Lyons,

were less lucky or perhaps more opinionated, having read the Bible

for themselves, and were duly condemned.

Old heresies like Manicheanism also resurfaced in new forms

like

Catharism and the

Albigensians. These were even more world-denying than medieval

Catholicism, which is no mean feat. The extreme asceticism of their

clergy, the perfecti, contrasted poorly with the established

and worldly Catholics, whom they saw as servants of a false creator

god.

The Christian hierarchy saw this as an assault from without, blaming

wandering minstrels and returning Crusaders, who may indeed have a

hand in spreading it along with the Bogomils, Manichean missionaries

from Bulgaria. It is from their alleged sexual practices that the

word bugger is said to come.

The cardinals suspected, however, that there was an organization

from outside Christendom behind it all. Indeed there may have been.

Modern scholarship has found evidence that the claim that there was

a "Cathar pope" directing operations before the Muslim invasion from

what is now Bosnia may have been accurate.

Thus, the Church realized it was in a

struggle for the very soul of Europe, and was willing to do whatever

it took to retain its control.

The worst

crime

To be called a heretic in the Middle Ages was a deadly serious

business. Due to the intertwining of Church and State, to be at odds

with one was to deny the other also. Heresy, a crime of the soul,

was treason, and treason, heresy.

As St. Thomas Aquinas confidently

wrote,

"If forgers and malefactors are put

to death by the secular power, there is much more reason for

excommunicating and even putting to death one convicted of

heresy."

Princes were thus often anxious to

co-operate and prove their orthodoxy, if only to keep suspicion from

themselves. For the Church said a heretic could not hold any office

legitimately; indeed, his lands and property were legally forfeit to

whatever good Christian could seize them.

The Inquisition got its bloody start during the long and vicious

Albigensian Crusade, where southern France was devastated by a

coalition of greedy lords from the north.

There was a basic problem distinguishing

devout Catholics from heretic

Cathars, which inspired one crusader to say,

"Slay them all, God will know his

own," and act accordingly.

Heresy was a thought-crime, a subversive

attitude against God's church, but hard to detect as it often

masqueraded as holiness.

Heretics craftily spoke in code and so

had to be tricked into exposing themselves, hence the use of torture

in interrogation, secret accusations, spies, and long-term

surveillance.

Techniques of

the theological thought police

The Inquisition became quite sophisticated in its approach. In the

medieval form, when an area was deemed to be infested with heretics

- say, when there had been resistance displayed to the excessive

donations, then a team of inquisitors would be sent in.

Armed with

authorizing documents from pope and prince, they would always travel

in pairs.

This not only allowed them to keep an

eye on each other, but permit them as priests to absolve each other

of any blood-spilling or other unpleasantness required in their

work. Inquisitors could not only go after anyone, they could absolve

anyone of any sin, sell the goods they confiscated, and got full

indulgences for their pains, so they could not only enrich

themselves in this life, but be assured of a well-earned paradise in

the next.

Accompanied by the local lord's guards, a chief minion called a

"familiar" and his stooges, and a secretary provided by the local

bishop to officially record the proceedings, the inquisitors would

parade into a town after it had been prepared by the vigorous

preaching of the local clergy, who would of course, all be in

attendance. There, at the chief church or cathedral, the inquisition

would be proclaimed in a grand public spectacle. A "general sermon"

would be read detailing the procedures and penalties, and all

sinners were invited to come forward and confess their sins on the

spot in order to be granted clemency.

Many, especially those who had seen an inquisition in action before,

would promptly do so. For it was not just a crime to be a heretic,

it was also a crime to be in any way favorable or merely impressed

by their seeming holiness.

"Fautors" or "listeners" were targeted

as were the most hardcore members of a movement. To be called a

fautor was an accusation quite enough to ruin one's life. And of

course, any hesitation, resistance, or questioning could be seen as

evidence of a dangerously bad attitude.

The penitents were of course required to inform on others in the

community, as were the clergy, who were under even more suspicion.

Innocent had proclaimed that the corruption of the people had

stemmed from that of the clergy, after all. A panel of judges would

be set up that might include local experts or representatives of the

religious establishment along with the inquisitors, and they would

quickly begin to debrief the clergy and penitents in secret.

Those unfortunates so named by their neighbors would soon be

ambushed or hauled off in the middle of the night by the chief

familiar and his crew. The very fact that the accused had not

already confessed was in itself suspicious. They would not be told

of what they were suspected, however; instead, they would be asked

if they knew why they had been arrested.

Even then, Catholic guilt was expected

to work wonders.

In that unhappy situation, the accused had a few small chances of

escaping unharmed. Claiming innocence was not usually one of them,

unless they could quickly and accurately name their unknown accuser

as an enemy. Such accusations were thrown out, one of the rare

safeguards in the system. Otherwise, if the accused confessed to the

right thing, it was a minor first offense and they cooperated fully

(usually by squealing on others), they might obtain leniency.

Usually, however, they were screwed,

plain and simple, and often literally.

Inquisitors busily at

their trade.

Notice the secretary

ready to record any confession that might gurgle past the drowning

victim's lips.

Under "vehement suspicion" of heresy, victims could be held

indefinitely at the whim of the inquisitor.

Sometimes this stretched into decades.

At any time, prisoners could be let out and brought back again for

the same offense. There were no limits on the number of times they

could be accused. Better food and conditions, even books on

occasion, could be procured from the familiars, who used this

privilege to line their pockets.

Property was frequently confiscated

outright, providing fuel for further persecutions since the

inquisitors were welcome to sell it off to finance their programs,

just as in the War on Drugs today. Most legal protections for

citizens that American citizens enjoyed until recently were

ultimately a reaction to the methods used by the inquisitors. The

Founding Fathers, suspicious of British tyranny, were even more

jaundiced against popery and its pretensions.

Suspects of the Inquisition could be denied the sacraments, even a

Christian burial. Years after their death, their bones could be dug

up and burnt, for there was no statute of limitations on heresy.

Even would-be saints were not immune. Armanno Porigilupo, for

instance, an Italian Cathar who was caught, recanted, and led a

saintly life thereafter, was hailed as a Catholic saint immediately

after his death, a grand altar erected over his tomb and was soon

said to have caused many miracles.

This quite outraged the local inquisitors.

Through five inquests,

nearly half a century, they argued until a papal commission decided

in 1301 the blessed Armanno had indeed been a secret Cathar all

along. His body was dug up and relics burned, the altar thrown down,

and the inquisitor became the new bishop. As in this case, all too

often the Inquisition was seen as political, a perception that grew

strong in Rome and Spain. The bloodiest inquisitors such as St.

Peter of Verona and Conrad of Marburg were not above wielding any

political influence to achieve their gory and paranoid ends.

Worst of all that could befall one was to relapse into error after

being once forgiven. For those, there could be no mercy for they

were deemed irredeemably corrupt. It was usually the stake for them

no matter what they pleaded.

If it came to torture, the options were as fertile as the fevered

inquisitors' imaginations. The first stage of torture was the mere

displaying of the instruments newly-forged just for the occasion to

the prisoner; the second was heating them up in front of the poor

wretch. Only then, in the "third degree," would they be actually

applied to flesh. The questioning would be methodical but devious,

and woe to any unfortunate soul about whose answers the secretary

noted, "the inquisitor was not satisfied."

Torture would proceed in gradual stages, until the inquisitor either

was contented or the accused had perished, though care was supposed

to be taken to prevent the latter.

As for theological questions, the safest

answer was,

"I believe whatsoever the holy

inquisitor instructs me to believe."

But even that was no guarantee.

If the questioner detected any evasion

or duplicity, he was required to be merciless for the sake of his

victim's soul.

Punishment as

propaganda

As the papal commission rightly points out, only a small proportion

were actually burnt. Many lesser punishments involved imprisonment

or fasting for years, publicly wearing garments, or placards, or

symbols, such as huge wooden dice for gamblers.

Monasteries, which already served the medieval world as hospitals,

hotels, libraries and research centers, took on the additional role

of religious prison. "Houses of the strict observance" were

particularly well-suited to locking up clerical criminals, but the

presence of men with no vocation or desire to be there was

inevitably corrupting. It actively contributed to the loss of esteem

that monks suffered leading up to the Reformation.

Those who were executed or publicly punished in some way were done

so in a closing spectacle even grander than the general sermon at

the beginning. The Church did not take the blame for the death

penalty; instead, it "relaxed" the victims into the tender mercies

of the State, which would then conduct the actual immolation.

But to claim the Church was therefore

not responsible for the burnings is about as believable as that it

was the low-ranking guards behind the photographed horrors in Iraq.

A Protestant view of

a late 17th century auto da fe in Lisbon.

One must have gotten away: on the far pyre, a mannikin is burning in

effigy.

The papal and Spanish "auto da fe" were important festive social

occasions to demonstrate the full might of Catholic power as well as

granting the condemned heretic a chance to show his or her mettle.

Huge processions with much pomp and ceremony would be undertaken to

the place of execution. If the heretic had escaped or was otherwise

unavailable, a dummy would be burnt in his place.

The lucky ones were strangled before burning; those who were being

used as a lesson, were not.

Giordano Bruno, for instance,

was burned alive in an iron mask that pierced his tongue so he

couldn't scream, and his agonized breath made it whistle.

Afterwards, the remains of such infamous heretics would be scattered

in the nearest river to prevent them from becoming relics.

In time, the Inquisition inspired some to try using its techniques

for social improvement. These gave mixed results in terms of

punishing adultery, gambling, and drunkenness. However, the

Inquisition was wildly successful in finding new sources of helpless

victims when it finally turned its attention to witchcraft.

At first, the inquisitors were forbidden to go after sorcerers

unless there was heresy involved. Only in the late fourteenth

century when the theologians decided that any resort to magic

involved worshipping the Devil and thus heresy that supposed

practitioners of the occult became fair game. Before this, for

instance, the learned doctors had believed that the witches'

sabbats were entirely illusory.

Once such dreadful things were

accepted as real, the dangers they presented to Christians then had

to be opposed - a classic case of creating one's own enemy.

Yet, even there the Inquisition was not entirely successful. In

Spain, for example, so many people came forward to confess to being

witches that the authorities could not handle the crowds. They

therefore reasoned that the people were deluded and there were no

brujas in Catholic Spain, and thus the Spanish Inquisition

busied themselves with crypto-Jews, Muslims, and Lutherans. (The

False Memory Syndrome people would have been pleased.)

Though it helped eliminate the Albigensians and Cathars, the

Inquisition ultimately failed in many respects. Proto-protestant

Waldensians, followers of Peter Waldo, fled to the mountains

and survived, as did the Hussites of Bohemia hundreds of years

later.

Finally, Martin Luther was able

to narrowly avoid the clutches of the Inquisition through princely

protection and public support mobilized by the new instrument of

free communication that the Church could not control, the printing

press. Ironically, that same invention had not long before spread

the infamous inquisitorial handbook,

The Hammer of the Witches, across

Europe.

In the mad times to follow, the

Protestants would do their own share of witch burning inspired by

its theories.

An inheritance

of iniquity

The Inquisition left in its wake a vast legacy of profound evil. It

refashioned the Catholic Church into an intellectual dictatorship, a

religious police-state where the appearance of conformity remains

all-important. To this day, secrecy still rules. And society has

paid the price.

Galileo, for example, learned

well the lessons left by Bruno, wisely denied the evidence of

his senses, and science has since languished in Italy.

As a result,

most of the great innovations of modern times and the material

wealth they have produced have mainly come from Protestant

dominions. With such enforced intellectual rigidity comes a stifling

of creativity in fields other than science as well. Everything from

theology to art is diminished and falsified.

The Inquisition did, of course, maintain the strictest control over

publishing in the Catholic sphere. It judged which books could be

published and which should be condemned. Hence the infamous Index

of Forbidden Books and the imprimatur system, whereby a bishop

would have to approve books for Catholics before they could be

printed. Needless to say, the tyrants of the world have found this

inspirational, too.

The operation of legal system by the Church, complete with dire

punishments, outside and overriding secular jurisdiction, buttressed

the expectation that the Catholic Church took care of its own, good

or bad. At one time, all it took was for an accused man to read the

Latin from the parish Bible to prove he was an educated cleric and

he would be turned over to the Church for judgment and discipline,

which was usually less harsh. This is what the term "benefit of

clergy" actually meant.

This attitude has been a major factor in the long cover-up of clergy

sexual abuse. The Church was expected to judge its failed ministers

and keep them away from the vulnerable laity. And thus there were

"treatment centers" essentially monasteries with programs of prayer

and meditation, like those of the Servants of the Paraclete

who basically enabled clerical perpetrators to be recycled from one

side of the continent to the other. This is a direct legacy of the

Inquisition and the medieval church.

The terror that was the Inquisition forced everything unacceptable

into the fetid underground it had created, both the sexual

acting-out of priests as well as unacceptable theology, where such

things were free to mingle and mutate. Its violence radicalized its

victims, too, some of who incorporated torture and bloodletting in

their own secret cults to order to learn to endure capture.

Paradoxically, the Inquisition is

therefore probably more responsible for the secret rings of criminal

clerical perpetrators and Satanists, in and out of the Church, than

anything else.

It could be expected the greatest harm done by the Inquisition is

that it has permanently stained the Roman Catholic Church,

discrediting it in the eyes of the world, forever causing its

motives to be doubted by outsiders who remember. But that oddly

enough, is not the case. The papacy, whose tool it was, should be

held in utter contempt and horror. After all, was not the

Inquisition the polar opposite of everything good that the Church

claims to be?

Perhaps the awareness of what people can do to their fellow humans

in the name of God is just too awful to contemplate for long.

Given the reactions to the sickening pictures from Iraq, that may

indeed be so.

In any event, the Inquisition itself endures. And now the former

head of its modern incarnation has become the Supreme Pontiff. Time

will tell if Pope Benedict XVI uses it to clear out the rot,

or drive the few remaining Catholics not already bound in

dogmatic chains from the temple.

We may not have to wait long.

|