|

from

Wikipedia Website

Galileo facing the

Roman Inquisition

The term Inquisition can refer to any

one of several institutions charged with trying and convicting

heretics within the

Roman Catholic Church and sometimes other

offenders against canon law.

It may refer to:

-

an ecclesiastical tribunal

-

the institution of the Roman

Catholic Church for combating or suppressing heresy

-

a number of historical

expurgation movements against heresy (orchestrated by the

Roman Catholic Church)

-

the trial of an individual

accused of heresy.

Inquisition tribunals

and institutions

Before the 12th century, the Western Christian Church already

suppressed what it saw as heresy, usually through a system of

ecclesiastical proscription or imprisonment, but rarely resorting to

torture or executions as this form of punishment had many

ecclesiastical opponents, although some non-secular countries

punished heresy with death penalty.

In the 12th century, in order to counter the spread of

Catharism, prosecutions against heresy became more

frequent. The Church charged councils composed of bishops and

archbishops with establishing inquisitions.

In the 13th century, Pope Gregory IX (reigned 1227-1241) assigned

the duty of carrying out inquisitions to the Dominican Order.

Inquisitors acted in the name of the Pope and with his full

authority. They used inquisitorial procedures, a legal practice

commonly used at the time. They judged heresy alone, using the local

authorities to establish a tribunal and to prosecute heretics. After

the end of the fifteenth century, a Grand Inquisitor headed each

Inquisition.

Inquisition in this way persisted until the

19th century.

In the 16th century, Pope Paul III established a system of

tribunals, ruled by the "Supreme Sacred Congregation of the

Universal Inquisition", and staffed by cardinals and other Church

officials. This system would later become known as the Roman

Inquisition. In 1908 Pope Pius X renamed the organization: it became

the "Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office".

This in its turn became the

Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith

in 1965, which name continues to this day.

Purpose

A

1578 handbook for inquisitors

spelled out the purpose of inquisitorial penalties:

... quoniam punitio non refertur

primo & per se in correctionem & bonum eius qui punitur, sed in

bonum publicum ut alij terreantur, & a malis committendis

avocentur.

[Translation from the Latin: "...

for punishment does not take place primarily and per se for the

correction and good of the person punished, but for the public

good in order that others may become terrified and weaned away

from the evils they would commit."]

Historic Inquisition

movements

Historians distinguish between four different manifestations of the

Inquisition:

-

the Medieval Inquisition (1184-

)

-

the Spanish Inquisition

(1478-1834)

-

the Portuguese Inquisition

(1536-1821)

-

the Roman Inquisition (1542-

~1860 )

Because of its objective — combating

heresy — the Inquisition had jurisdiction only over baptized members

of the Church (which, however, encompassed the vast majority of the

population in Catholic countries). Secular courts could still try

non-Christians for blasphemy. (Most of the witch trials went through

secular courts.)

Different areas faced different situations with regard to heresies

and suspicion of heresies. Most of Medieval Western and Central

Europe had a long-standing veneer of Catholic standardization, with

intermittent localized outbreaks of new ideas and periodic

anti-Semitic/anti-Judaic activity.

Exceptionally, Portugal and Spain in the

late Middle Ages consisted largely of multi-cultural territories

fairly recently conquered from Muslim control, and the new overlords

could not assume that all their newer subjects would suddenly become

and remain compliant true-believer orthodox Catholics. So the

Inquisition in Iberia had a special socio-political basis as well as

more conventional religious motives.

With the rise of Protestantism and ideas

of the Renaissance perceived as heretical by the Catholic church,

the extirpation of heretics became a much broader and more complex

enterprise, complicated by the politics of territorial Protestant

powers, especially in northern Europe: war, massacres and the

educational and propagandistic work of the Counter-Reformation

became more common than a judicial approach to heresy in these

circumstances.

Medieval Inquisition

Historians use the term 'Medieval Inquisition" to describe the

various inquisitions that started around 1184, including the

Episcopal Inquisition (1184-1230s) and later the Papal Inquisition

(1230s).

These inquisitions comprised the legal response to large

popular movements throughout Europe considered apostate or heretical

to Christianity, in particular

the Cathars and Waldensians in southern France and

northern Italy.

Other Inquisitions followed after these

first inquisition movements.

Legal basis for some inquisitorial activity came from Pope Innocent

IV's papal bull Ad exstirpanda of 1252, which authorized and

regulated the use of torture in investigating heresy.

Spanish Inquisition

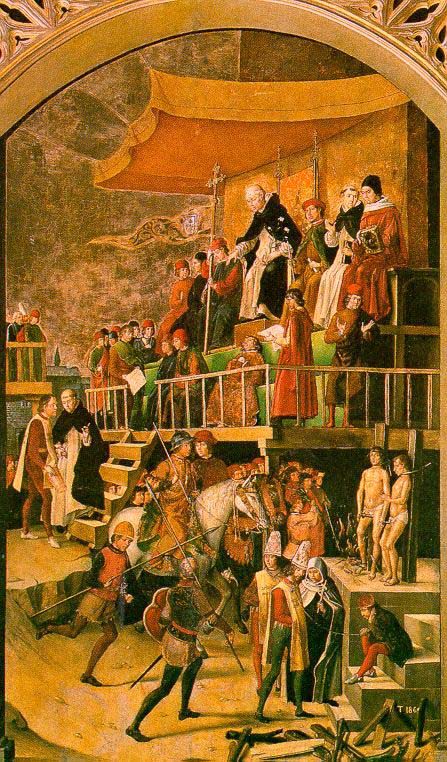

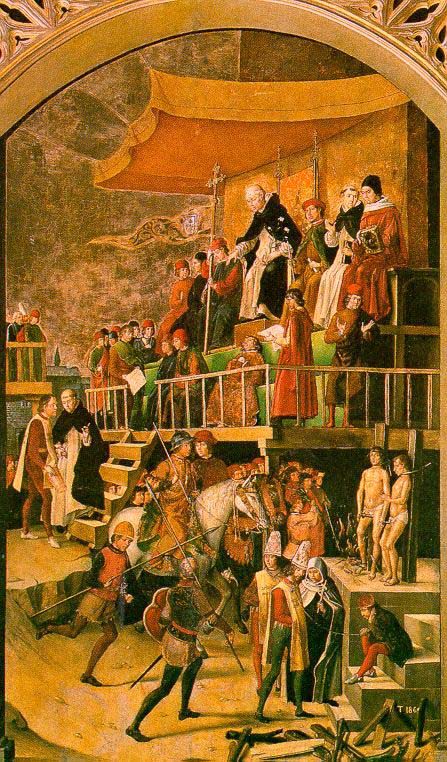

Representation of an

Auto de fe, (around 1495).

Many artistic representations depict torture and burning at the

stake as occurring during the auto da fe.

King Ferdinand II of Aragon and

Queen Isabella I of Castile set up the Spanish Inquisition in 1478

with the approval of Pope Sixtus IV.

In contrast to the previous

inquisitions, it operated completely under royal authority, though

staffed by secular clergy and orders, and independently of the Holy

See.

It targeted primarily converts from

Judaism (Marranos or secret Jews) and from Islam (Moriscos

or secret Moors) — both formed large groups still residing in

Spain after the end of the Moorish control of Spain — who came under

suspicion of either continuing to adhere to their old religion

(often after having converted under duress) or of having fallen back

into it.

Somewhat later the Spanish Inquisition

took an interest in Protestants of virtually any sect, notably in

the Spanish Netherlands. In the Spanish possessions of the Kingdom

of Sicily and the Kingdom of Naples in southern Italy, which formed

part of the Spanish Crown's hereditary possessions, it also targeted

Greek Orthodox Christians. After the intensity of religious disputes

waned in the 17th century, the Spanish Inquisition developed more

and more into a secret-police force working against internal threats

to the state.

The Spanish Inquisition also operated in the Canary Islands.

King Phillip II set up two tribunals (formal title: Tribunal del

Santo Oficio de la Inquisición) in the Americas, one in Peru

and another in Mexico.

The Mexican office administered the

Audiencias of:

-

Guatemala (Guatemala, Chiapas,

El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica)

-

Nueva Galicia (northern and

western Mexico)

-

the Philippines.

The Peruvian Inquisition, based in Lima,

administered all the Spanish territories in South America and

Panama. From 1610 a new Inquisition seat established in Cartagena

(Colombia) administered much of the Spanish Caribbean in addition to

Panama and northern South America.

The Inquisition continued to function in North America until the

Mexican War of Independence (1810-1821).

In South America Simón Bolívar

abolished the Inquisition; in Spain itself the institution

survived until 1834.

Portuguese

Inquisition

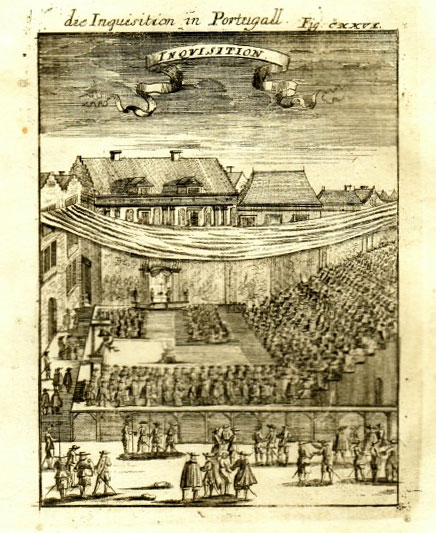

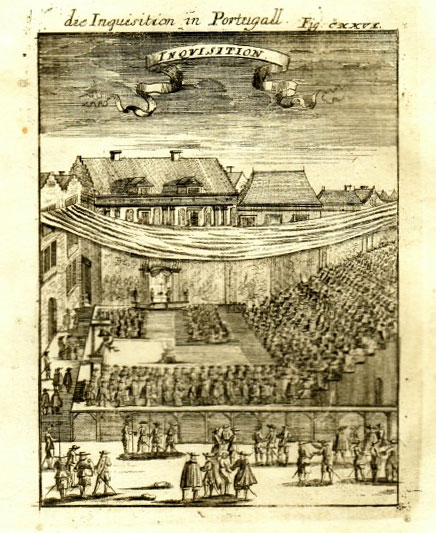

Copper engraving

intitled "Die Inquisition in Portugall", by Jean David Zunner

from the work

Description de L'Univers, Contenant les Differents Systemes de

Monde,

Les Cartes Generales

& Particulieres de la Geographie Ancienne & Moderne

by Alain Manesson

Mallet, Frankfurt, 1685.

The Portuguese Inquisition formally

started in Portugal in 1536 at the request of the King of Portugal,

João III.

Manuel I had asked Pope Leo X for the

installation of the Inquisition in 1515, but only after his death

(1521) did Pope Paul III acquiesce. However, many place the actual

beginning of the Portuguese Inquisition during the year of 1497,

when the authorities expelled many Jews from Portugal and forcibly

converted others to Catholicism.

The major target of the Portuguese

Inquisition were mainly the Sephardic Jews that had been expelled

from Spain in 1492 (see Alhambra decree); after 1492 many of these

Spanish Jews left Spain for Portugal but were eventually targeted

there as well.

The Inquisition came under the authority of the King. At its head

stood a Grand Inquisitor, or General Inquisitor, named by the Pope

but selected by the Crown, and always from within the royal family.

The Grand Inquisitor would later nominate other inquisitors. In

Portugal, the first Grand Inquisitor was Cardinal Henry, who would

later become King. There were Courts of the Inquisition in Lisbon,

Porto, Coimbra, and Évora.

The Portuguese Inquisition held its first auto da fé in

Portugal in 1540.

It concentrated its efforts on rooting out

converts from other faiths (overwhelmingly Judaism) who did not

adhere to the strictures of Catholic orthodoxy; the Portuguese

inquisitors mostly targeted the Jewish "New Christians,"

conversos, or marranos.

The Portuguese Inquisition expanded its scope of operations from

Portugal to Portugal's colonial possessions, including Brazil, Cape

Verde, and Goa, where it continued as a religious court,

investigating and trying cases of breaches of the tenets of orthodox

Roman Catholicism until 1821.

King João III (reigned 1521-1557) extended the activity of the

courts to cover book-censorship, divination, witchcraft and bigamy.

Book-censorship proved to have a strong influence in Portuguese

cultural evolution, keeping the country uninformed and culturally

backward. Originally oriented for a religious action, the

Inquisition had an influence in almost every aspect of Portuguese

society: politically, culturally and socially.

The Goa Inquisition, another inquisition rife with antisemitism and

anti-Hinduism and which mostly targeted Jews and Hindus, started in

Goa in 1560. Aleixo Dias Falcão and Francisco Marques set it up in

the palace of the Sabaio Adil Khan.

According to Henry Charles Lea between 1540 and 1794

tribunals in Lisbon, Porto, Coimbra and Évora resulted in the

burning of 1,175 persons, the burning of another 633 in effigy, and

the penancing of 29,590. But documentation of fifteen out of 689

Autos-da-fé has disappeared, so these numbers may slightly

understate the activity.

The "General Extraordinary and Constituent Courts of the Portuguese

Nation" abolished the Portuguese inquisition in 1821.

Roman Inquisition

In 1542, Pope Paul III established the Congregation of the

Holy Office of the Inquisition as a permanent congregation

staffed with cardinals and other officials.

It had the tasks of maintaining and

defending the integrity of the faith and of

examining and proscribing errors and false

doctrines; it thus became the supervisory body of local

Inquisitions.

Arguably the most famous case tried by the

Roman

Inquisition involved Galileo Galilei in 1633. Because of

Rome's power over the Papal States, Roman Inquisition activity

continued until the mid-1800s.

In 1908 the name of the Congregation became "The Sacred Congregation

of the Holy Office", which in 1965 further changed to "Congregation

for the Doctrine of the Faith", as retained to the present day.

The

Congregation is presided by a cardinal appointed by the Pope, and

usually includes ten other cardinals, as well as a prelate and two

assistants all chosen from the Dominican Order.

The Holy Office also has an

international group of consultants, experienced scholars of theology

and canon law, who advise it on specific questions.

List of Spanish Grand Inquisitors

-

Tomás de Torquemada, prior of

Santa Cruz 1483 - 1498

-

Diego de Deza Tavera, prior of

Santo Domingo 1499 - 1506

-

Diego Ramírez de Guzmán, bishop

of Catania, bishop of Lugo 1506 - 1507

-

Francisco Ximénez de Cisneros,

archbishop of Toledo 1507 - 1517

-

Juan Enguera, bishop of Vich,

bishop of Lleida, Tortosa 1507 - 1513

-

Luis Mercader Escolano, bishop

of Tortosa 1513 - 1516

-

Adrian of Utrecht 1516 - 1522

-

Alonso Manrique de Lara,

archbishop of Seville 1523 - 1538

-

Juan Pardo de Tavera, archbishop

of Toledo 1539 - 1545

-

García de Loisa, archbishop of

Seville 1546

-

Fernando de Valdés y Salas 1547

- 1566

-

Diego de Espinosa, bishop of

Sigüenza, bishop of Cuenca 1566 - 1572

-

Pedro Ponce de León, bishop of

Ciudad Rodrigo, bishop of Plasencia 1572

-

Gaspar de Quiroga y Vela ,

archbishop of Toledo 1573 - 1594

-

Jerónimo Manrique de Lara,

bishop of Cartagena, bishop of Ávila 1595

-

Pedro de Portocarrero, bishop of

Calahorra, bishop of Cuenca 1596 - 1599

-

Hernando Niño de Guevara,

archbishop of Philipis, archbishop of Seville 1599 - 1602

-

Juan de Zúñiga Flores, bishop of

Cartagena 1602

-

Juan Bautista de Acevedo, bishop

of Valladolid and Patriarch of the Indias 1603 - 1608

-

Bernardo de Sandoval y Rojas,

archbishop of Toledo 1608 - 1618

-

Luis de Aliaga Martínez 1619 -

1621

-

Andrés Pacheco, bishop of Cuenca

and Patriarch of the Indias 1622 - 1626

-

Antonio de Zapata Cisneros y

Mendoza, archbishop of Burgos 1627 - 1632

-

Antonio de Sotomayor, prior of

Santo Domingo 1632 - 1643

-

Diego de Arce y Reinoso, bishop

of Tuy, Ávila and Plasencia 1643 - 1665

-

Pascual de Aragón y Fernández de

Córdoba, archbishop of Toledo 1665

-

Juan Everardo Nittard 1666 -

1669

-

Diego Sarmiento de Valladares,

bishop of Oviedo and Plasencia 1669 - 1695

-

Juan Tomás de Rocaberti, prior

of Santo Domingo and archbishop of Valencia 1695 - 1699

-

Alonso Fernández de Córdoba y

Aguilar 1699

-

Baltasar de Mendoza y Sandoval,

bishop of Segovia 1699 - 1705

-

Vidal Martín, archbishop of

Burgos 1705 - 1709

-

Antonio Ibáñez de Riva Herrera,

archbishop of Zaragoza and Toledo 1709 - 1710

-

Antonio Judice, archbishop of

Monreal 1711 - 1717

-

José Molines 1717

-

Felipe de Arcemendi 1718

-

Diego de Astorga y Céspedes,

archbishop of Toledo 1720

-

Juan de Camargo y Angulo y

Pasquer, bishop of Pamplona 1720 - 1733

-

Andrés de Orbe y Larreategui,

archbishop of Valencia 1733 - 1740

-

Manuel Isidro Orozco Manrique de

Lara, archbishop of Santiago 1742 - 1745

-

Francisco Pérez de Prado y

Cuesta, bishop of Teruel 1746 - 1755

-

Manuel Quintano Bonifaz,

archbishop of Farsalia 1755 - 1774

-

Felipe Beltrán, bishop of

Salamanca 1775 - 1783

-

Agustín Rubin de Ceballos,

bishop of Jaén 1784 - 1793

-

Manuel Abad y Lasierra,

archbishop of Selimbria 1793 - 1794

-

Francisco Antonio Lorenzana y

Butrón, archbishop of Toledo 1794 - 1797

-

Ramón José de Arce y Rebollar,

archbishop of Amida, Burgos and Zaragoza 1797 - 1798

-

Francisco J.Mier y Campillo,

bishop of Almería 1814 - 1818

-

Jerónimo Castillón y Salas,

bishop of Tarazona 1818 - 1820

|