|

A fascinating new paper theorizes that alien civilizations could do the same thing, reshaping their homeworlds in predictable and potentially detectable ways.

The authors are proposing

a new classification scheme that measures the degree to which

planets been modified by intelligent hosts.

Examples include,

With ongoing advances in telescope technology, the day is coming when astronomers will be able to expand on these simple characterizations, classifying a planet according to other features, including atmospheric or chemical composition.

But as a new study (Earth as a Hybrid Planet - The Anthropocene in an Evolutionary Astrobiological Context) led by University of Rochester astrophysicist Adam Frank points out, we may eventually be able to place exoplanets within an astrobiological context, too.

In addition to taking the usual physical measures into account, Frank and his colleagues are proposing that astronomers take the influence of a hypothetical planet's biosphere into account - including the impacts of an advanced extraterrestrial civilization.

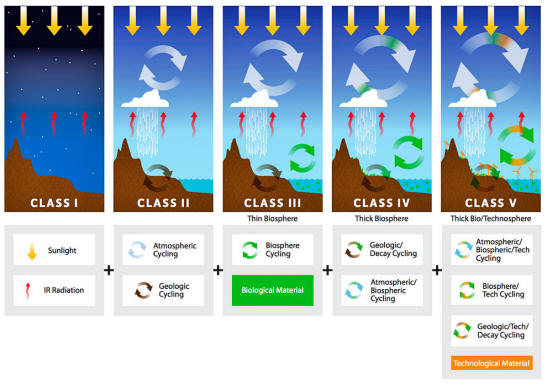

Frank's hypothetical planets, ranked from Class I through to Class V, range from dead, rocky worlds through to planets in which a host intelligence has solved the problems caused by its own existence, like excessive use of resources and climate change.

Moreover, as Frank explained to us, this paper presents more than just a planetary classification scheme - it's a potential roadmap to an environmentally viable future.

If we discover signs of an advanced alien civilization - and that's a 'big if' - we may learn a thing or two about how we might be able to survive into the far future.

Indeed, we're at a critical juncture in our history, one in which we're crafting the planet according to our will - and so far, we're not doing a very good job of it.

There's ongoing debate as to whether or not our planet has crossed into the Anthropocene epoch, a new geologic chapter in which we've become the primary driver of planetary change.

Some scientists point to the fact that half of the planet's land surface has been claimed for human use, or that Earth's biogeochemical cycles of nitrogen and phosphorus have been radically altered on account of agriculture and fertilizer use, as evidence that we have.

The US Eastern seaboard at night. (Image: NASA)

While the technical debate over what constitutes evidence of a geologic shift continues, it's clear humanity is altering Earth in some rather profound ways.

So much so, says Frank, that we need to place our planet, and the Anthropocene itself, within an astro-biological context.

What's happening here on Earth, says Frank, is likely happening elsewhere in the Galaxy.

Though we may be inclined to think that our situation is somehow special or unique, we have no good reason to believe that's really the case.

Frank goes to far as to say that virtually every advanced civilization like 'ours', should they exist, has to tackle the issue of climate change at some point in its development.

As the new paper points out, humanity, or any alien intelligence for that matter, is simply another expression of the biosphere:

Which is where the new planetary classifications come in.

In their new paper (Earth as a Hybrid Planet - The Anthropocene in an Evolutionary Astrobiological Context), Frank and his colleagues consider the history of coupled Earth systems, that is, the tightly bound relationship between the planet's atmosphere, ocean, ice, lithosphere (the ground), and biosphere.

All these systems affect each other, changing the overall constitution of the planet.

Without the biosphere, for example, we wouldn't have oxygen. And today, with our copious greenhouse gas emissions, we're affecting the atmosphere even further.

With this in mind, the authors present a planetary classification scheme based on,

Under the proposed scheme,

Image: Frank et al., 2017

At this stage, says Frank, a civilization has learned how to think like a planet, and it's figured out the rules of the game.

It's able to modify and adjust its own activities, and likely the biosphere itself, such that the civilization - and planet - can be sustainable over the long-term.

Frank suspects that we'll eventually be able to detect Class V planets, picking up on various techno-signatures, such as those produced by massive planetary solar farms, or signs of energy being converted into useful work, leading to an unusual increase in energy dissipation not indicative of natural sources.

Not coincidentally, this scheme is reminiscent of the Kardashev scale - an attempt to classify the amount of energy available to hypothetical extraterrestrial civilizations.

According to this scheme,

Frank says that his proposed planetary scale can work alongside the Kardashev schema, but that in order for a civilization to reach KII status it must first inhabit a Class V planet.

Frank says his team's proposed planetary classifications are just a start, and that their team is merely pointing towards a potential new area of research.

Image: NASA

Avi Loeb, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who wasn't involved in the new study, says the new framework has practical connections to future observations of planetary atmospheres, while also encouraging us to reflect on the effect we have on Earth.

Anders Sandberg, a researcher at Oxford's Future of Humanity Institute, likes the "thermodynamic" approach, saying that civilizations are physical systems, too.

Sandberg, who wasn't involved in the new study, wonders if the classification system can include higher levels, such as Class VI or VII planets, and include something beyond a purely technological civilization.

But the problem as he sees it is that it may be difficult to tell the levels apart.

No doubt, Frank's new classification system is far from perfect and certainly not complete.

But like in any burgeoning field, there are more mysteries than there are answers.

Hopefully, with the next generation of space-based telescopes we'll start to detect these techno-signatures in the atmospheres of distant exoplanets and take inspiration from civilizations that have somehow figured out a way to live in harmony with their planet.

It's also entirely possible that our searches will yield nothing.

Our technologies may never get so advanced that we can detect bio-signatures of microbial life on other planets, let alone the subtle differences between a Class IV and V planet. What's more, we have no reason to believe that a Class V planet even exists.

Our current technological stage may be as advanced as it gets, with resource depletion, pollution, climate change, and apocalyptic technologies serving as impenetrable filters.

That doesn't mean we shouldn't look.

If we find nothing, we'll remain in the same bubble of ignorance we currently find ourselves in now. But if we find bio-signatures or alien radio emissions, we'll finally know life is possible elsewhere.

We may even find a batch of Class I-IV planets, but not a single Class V planet, which would be alarming.

But as is often said, absence of evidence isn't evidence of absence.

|