|

by Kellia Ramares

March 2003

from

Scribd Website

- South Africa,

Israel Have Sought "Ethnic Bombs"

- Genetic "Agroterrorism" Could Look Like an "Act of

God" and the U.S., the Worlds' Biotech leader, Could

become the Biggest Victim

***

Kellia Ramares

earned a B.A. degree in economics, with honors, from

Fordham University in New York in 1977. She also earned

a law degree from Indiana University-Bloomington in

1980. She has been a reporter for KPFA-FM in Berkeley,

CA for nearly four years. There, her specialty is toxics

reporting.

Kellia is also an

Associate Producer for WINGS - Women's International

News Gathering Service, a Contributing Editor for

OnlineJournal.com and a reporter for Free Speech Radio

News, which is heard in over 50 stations throughout the

United States.

Kellia's latest project is

R.I.S.E. - Radio Internet Story Exchange, a weekly

Internet-based public affairs program. The R.I.S.E.

website is

http://www.rise4news.net

|

Part 1

March 4, 2003

Since the attacks of

9-11-01 there has been a great

deal of discussion and speculation as to whether or not

gene-specific bioweapons might be used as a weapon of war or, in

the gloomiest of scenarios, as an instrument of global

population reduction to alleviate the inevitably drastic

consequences of Peak Oil.

FTW asked radio public affairs

producer and investigative journalist Kellia Ramares to

take a critical look at whether such weapons actually exist.

While not definitively establishing that such weapons do exist,

Ramares had documented, in chilling detail, both their

scientific feasibility of such weapons and the fact that many

nations have been actively pursuing them for some time.

- MCR

"...to the extent that any country were to attack us with

nuclear weapons then we obviously have a nuclear response. With

respect to biologicals and chemicals, we have indicated it would

be a swift, devastating response and overwhelming force. We have

not indicated what that might entail. We've left that

deliberately open."

- Secretary of Defense

William S. Cohen in an interview for the PBS "Frontline" program

"Plague Wars" aired on 10.13.98

Mar. 4, 2003, 00:30 PST (FTW)

Biological and chemical weapons are as old as the discovery of

poison.

Examples of chemical warfare go back at

least as far as Ancient Greece, where Solon of Athens poisoned his

enemy's water supply during the siege of Krissa in 6th Century

B.C.E.1

In Europe, biological weapons, in the

form of the bodies of plague victims being catapulted over the walls

of a besieged city, go back to at least the year 1346.2

In 18th Century North America, Indian populations were given

smallpox infected blankets during the French and Indian War.3

In modern times, there is evidence of a

World War II-era Japanese biological weapons program and Japanese

use of plague against the civilian Chinese population of Chiangking

Province.4 Out of World War II came the mushroom cloud

that still haunts popular imagination. But the still-unsolved

anthrax attacks in the U.S. in October 2001 and the White House's

insistence that Iraq is concealing chemical and biological weapons

has again brought these types of weapons to public attention.

The Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention 5

prohibits the development, production and stockpiling of biological

and toxic weapons. The BTWC was signed on April 10, 1972, and

entered into force on March 26, 1975. The Convention is a

disarmament treaty, meant to "exclude completely the possibility" of

biological agents and toxins being used as weapons by abolishing the

weapons themselves.6

The United States, the United Kingdom, and several countries thought

by the United States Government to have bioweapons programs are

original signatories to the BTWC. These include the Russian

Federation, Iran, South Africa, South Korea and Syria.7

North Korea, Iraq and Libya subsequently signed the convention.8

The United States ratified the BTWC on March 26, 1975.9

Non-signatories include several former

Soviet republics in volatile Central Asia: Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan,

Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan.10

The BTWC forbids work on offensive biological weapons. Perhaps the

most egregious violation of the Convention has been the former

Soviet Union's offensive biological weapons program. 11

The Convention allows defensive biological work, such as the

development of vaccines.

However, the line between defensive and

offensive work is very thin; in order to make a vaccine or an

antidote, one must first learn how a pathogen works, and that

information could be put to offensive use.

Biological and

Chemical Weapons - Is their use inevitable?

In 1997, Secretary of Defense William S. Cohen reported that more

than 25 countries had - or may be developing - nuclear, biological and

chemical (NBC) weapons and the means to deliver them, and that a

larger number were capable of producing such weapons, potentially on

short notice.12

There are a number of reasons why, despite the BTWC, the use of

biological and chemical weapons becomes more and more likely:

-

It is extremely difficult to

monitor the creation of bioweapons because there are no

critical raw materials, e.g. uranium or plutonium, the

mining, manufacture or transportation of which could be

evidence of the creation of the weapon; a small amount of a

bioagent can do a lot of damage, so no major stockpiling is

needed 13

-

Bioweapons are cheap compared to

conventional and nuclear weapons, and can be economically

developed through computer modeling. Furthermore, bioweapons

do not require a large and expensive delivery infrastructure

of conventional weapons, i.e. planes, aircraft carriers,

missiles, etc.14 For example, anthrax was sent

through the U.S. mails in 2001

-

The spread of human, animal or

crop disease can be made to look like an "act of God" with

no one able to trace the perpetrator(s) 15

Additionally, smaller states with little

or no nuclear capability can view chemical and biological weapons as

a counterforce to the heavy nuclear and conventional capabilities of

the United States, which is threatening possibly nuclear "preemptive

action" under the so-called "Bush Doctrine." 16

Biological and chemical weapons can be used by countries,

corporations, terrorist groups, organized crime and disaffected or

mentally ill individuals who would not have the means to build up a

conventional or nuclear arsenal.

Properly deployed, they have the

capability of rapidly killing more people than a nuclear weapon.

In an interview for the PBS television

program Frontline in 1998, then Secretary of Defense William S.

Cohen said,

"If you look at the impact that a

biological weapon can have, in terms of its cost and

consequence, you will find that it does not take a great deal to

develop it in terms of money. It has a major consequence if you

were to, for example, take roughly 100 kilograms (about 220

pounds) of anthrax and you were to properly disperse [it], that

would have the impact of something like two to six times the

consequence of a one megaton nuclear bomb." 17

Moreover, the May 1997 Report of the

Quadrennial Defense Review stated:

"...the threat or use of chemical

and biological weapons (CBW) is a likely condition of future

warfare, including in the early stages of war to disrupt U.S.

operations and logistics. These weapons may be delivered by

ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, aircraft, special

operations forces, or other means.

To meet this challenge, as well as

the possibility that CBW might also be used in some

smaller-scale contingencies, U.S. forces must be properly

trained and equipped to operate effectively and decisively in

the face of CBW attacks. This requires that the U.S. military

continue to improve its capabilities to locate and destroy such

CBW, preferably before they can be used, and defend against and

manage the consequences of CBW if they are used. But capability

enhancements alone are not enough.

Equally important will be adapting

U.S. doctrine, operational concepts, training, and exercises to

take full account of the threat posed by CBW as well as other

likely asymmetric threats. Moreover, given that the United

States will most likely conduct future operations in coalition

with others, we must also encourage our friends and allies to

train and equip their forces for effective operations in CBW

environments." 18

The adaptation to future warfare

involving CBW is being done in such as way as to increase the

likelihood of such a war.

The United States, and perhaps other

nations as well, is engaging in so-called defensive research known

as "threat assessment." That means creating the threat or a simulant

of it, and testing its delivery by various means in order to assess

how harmful it could be.

Dr. Barbara Hatch Rosenberg, Chair of the Federation of

American Scientist's Working Group on Biological Weapons and

Director of the Federation's Chemical and Biological Arms Control

Program, has written that the outcome of threat assessment "may

be a covert international arms race to stay at the cutting edge of

BW development, using defence as a cover." 19

To make matters worse, the United States is moving toward more

secrecy about the general conduct of its defensive research, a

practice which could make other nations suspicious about the true

nature of the research. It's also appears that the U.S. is up to

lawyerly tricks to evade the requirements of the Biological and

Toxin Weapons Convention.

Dr. Rosenberg has reported:

It is startling to find, in the

Assessment Report of a meeting of US and UK defense officials,

that 'in the US these [relevant treaties, including the BWC] do

not apply to the Department of Justice (DOJ) or Department of

Energy.' Therefore, the Report lists as one of the Recommended

Actions for the US: 'If there are promising technologies that

DoD is prohibited from pursuing, set up MOA [memoranda of

agreement] with DOJ or DOE.'

The US delegation to this event -

the Non-Lethal Weapons Urban Operations Executive Seminar, held

in London on November 30, 2000 - was led by four US Marine Corps

Generals, including one who was Staff Judge Advocate to the

Commandant of the Marine Corps.20

Chemical and biological weapons (CBW)

create the possibility of warfare in which battlefields are

intentionally or unintentionally rendered obsolete, as it may not be

possible to confine diseases or chemicals to a limited geographical

area.

They also ensure a future of warfare,

perhaps a very near future, in which civilians are not "collateral

damage" but the prime targets. And the combination of a lowered

moral barrier towards CBW, the stirring up of ages-old ethnic

hatreds, and advances in genome research within the last decade has

brought the genocidal possibility of genetic weapons, i.e., weapons

that target some component of the genetic makeup (genome) of its

victim, closer to reality.

So far, there is no proof that genetic weapons targeting any

organism have actually been developed. But several countries have

researched or are researching the subject.

The possibilities for

genetic weapons range from botanical pathogens that could wipe out a

region's crops in an act of military or economic warfare, or

terrorism, to the ultimate Hitlerian nightmare: the "ethno-bomb," a

weapon targeted at unique or nearly unique genetic characteristics

of a population.

For the purposes of this article,

pathogens that can harm anyone, but which are distributed,

intentionally or accidentally, to a specific racial or ethnic group

are not considered "ethno-bombs" or "ethnic weapons."

A strong case for HIV being a laboratory

created virus distributed intentionally or accidentally to Central

Africa and the New York gay community via smallpox and hepatitis B

vaccines is made by Dr.

Leonard Horowitz in

Emerging Viruses: AIDS & Ebola - Nature, Accident or Intentional?

(1996).

In the worst case scenario of unintended

consequences, government and corporate genome research intended for

legitimate medical applications may someday provide the knowledge

required to develop genetically specific ethnic weapons.

"Ethno-Bombs"

-

Warnings were raised a decade ago

In 1993, RAFI, Rural Advancement Foundation International,

now the ETC Group - Action Group on Erosion, Technology and

Concentration,21 raised concerns that the gathering

of human genetic material by, among other organizations, the

Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP) could make feasible the

development of ethnically targeted viruses.22

RAFI's executive director, Pat Roy Mooney wrote:

"Not since we warned, at the

beginning of the 1980s, that herbicide manufacturers were buying

seed companies in order to develop plant varieties that liked

their chemicals, has RAFI borne the brunt of so much abuse."

23

But in 1996, Dr. Vivienne Nathanson,

the British Medical Association's (BMA) Head of Science and

Ethics told a congress of the World Medical Association that

ethnically targeted genetic weapons were now possible, and she cited

as example the possibility of designing an agent that could

sterilize or pass on a lethal hereditary defect in specific ethnic

groups.24

In 1999, the BMA issued a report called

Biotechnology, Weapons and Humanity

25, which warned that genetic knowledge could be misused

to develop weapons aimed at specific ethnic groups.

The executive summary (below

insert)

stated:

Over the last few decades rapid

advances in molecular biology have allowed the heritable

material (DNA) of different organisms to be interchanged. The

Human Genome Project and

the

Human Genome Diversity Projects

are allowing the identification of human genetic coding and

differences in normal genetic material between different ethnic

groups.

During the review conferences on the BTWC, an increasing level

of concern has been expressed by national governments over the

potential use of genetic knowledge in the development of a new

generation of biological and toxin weapons.

Legitimate research into microbiological agents, relating both

to the development of agents for use in, for example

agriculture, or to improve the medical response to disease

causing agents, may be difficult to distinguish from research

with the malign purpose of producing more effective weapons.

Research that could be used to develop

ethnic weapons has historically been based upon natural

susceptibilities, or upon the absence of vaccination within a target

group.

Genetic engineering of biological

agents, to make them more potent, has been carried out covertly for

some years, but not as an overt step to produce more effective

weapons. In genetic terms there are more similarities between

different people and peoples than there are differences.

But the differences exist, and may

singly or in combination distinguish the members of one social group

(an "ethnic" group) from another.26

|

Biotechnology, Weapons and

Humanity

from

Genetech Website

Structure and scope of report

The aim of the report is to consider new developments in

biotechnology, especially human genetics, which could be

incorporated into the available weaponry of nation

states and terrorist organizations. In particular, the

report considers whether weapons could be based on

genetic knowledge and if so, how legislation and other

measures could prevent such a malign use of scientific

knowledge.

This chapter sets out the aims and objectives of the

report within the context of concern shown by the

medical profession at the 48th WMA meeting held in South

Africa in 1996. Chapter 2 provides a history of

offensive biological weapons programs and of

international arms control efforts in the twentieth

century to prohibit such programs. Chapter 3 then

outlines the major features of the modern biotechnology

revolution and why this has caused such concerns about

the possible development of new biological weapons.

As an example of

these concerns, the possible development of ‘ethnic’

weapons based on advances in our understanding of human

genetics and targeted at specific racial/ethnic groups

is examined in Chapter 4. In Chapter 5 the currently

available mechanisms of control of offensive biological

weapons programs are described, and in Chapter 6

suggestions for further measures to help deter states

and organizations from developing such weapons are

reviewed. Chapter 7 presents recommendations for action

and further research by the scientific and medical

community, both nationally and also on an international

basis.

As will become apparent, biological weapons come in many

forms and can be used in many different ways. However,

the main cause for concern is that these weapons, which

are basically unregulated and rather easy to develop,

could proliferate in areas of regional instability, or

enter the available weaponry of terrorists. Such

proliferation should be viewed in the context that since

1948 the United Nations have considered biological

weapons as weapons of mass destruction, i.e. in the same

category as nuclear weapons.

This report discusses the relationship between medicine,

biotechnology and humanity. It considers the development

of weapons which may become a major threat to the

existence of Homo sapiens, and a development of

biotechnology which perverts the humanitarian nature of

biomedical science. It is all the more frightening that

medical professionals may contribute, willingly or

unwittingly, to the development of new, potent weapons.

This potential for malign use of biomedical knowledge

also places responsibility on doctors and scientists to

protect the integrity of their work.

Genetic engineering can be of great benefit to medical

science and humanity, but can also be used for harm.

Genetic information is already being used to improve

elements of biological weapons — such as increased

antibiotic resistance — and it is likely that this trend

will accelerate as the knowledge and understanding of

its applications become more widely known, unless

effective control systems can be agreed.

The pattern of

scientific development is such that developing effective

control systems within the next five to ten years will

be crucial to future world security.

Executive summary

The world faces the prospect that the new revolution in

biotechnology and medicine will find significant

offensive military applications in the next century,

just as the revolutions in chemistry and atomic physics

did in the twentieth century. Biological weapons have

been used sporadically in conflicts throughout history.

They have been

developed in line with scientific advances, making them

increasingly potent agents. Since 1948 they have been

categorized as weapons of mass destruction. Despite the

1925 Geneva Protocol and the 1975 Biological and Toxin

Weapons Convention (BTWC) they are, in reality, poorly

regulated and controlled.

Prohibitions on the development and use of biological

and toxin weapons have not been fully effective; intense

and urgent efforts are needed to make the BTWC an

effective instrument. Biological weapons may already be

in the hands of a number of countries, and are also a

realistic weapon for some terrorist groups. Control

mechanisms must address not only the types of agents

which might be used as weapons, and the protection

against, and response to, their use, but also the

ability of non-governmental groups to possess and use

such weapons.

Over the last few

decades rapid advances in molecular biology have allowed

the heritable material (DNA) of different organisms to

be interchanged. The Human Genome Project and the Human

Genome Diversity Projects are allowing the

identification of human genetic coding and differences

in normal genetic material between different ethnic

groups.

During the review conferences on the BTWC, an increasing

level of concern has been expressed by national

governments over the potential use of genetic knowledge

in the development of a new generation of biological and

toxin weapons.

Legitimate research into microbiological agents,

relating both to the development of agents for use in,

for example agriculture, or to improve the medical

response to disease causing agents, may be difficult to

distinguish from research with the malign purpose of

producing more effective weapons.

Scientists should recognize the pressures that can be

brought to bear on them, and on their colleagues, to

participate in the development of weapons.

The recent history of conflict is predominantly of wars

within states, often between different ethnic groups.

Consideration of ethnic weapons have historically been

based upon natural susceptibilities, or upon the absence

of vaccination within a target group. Genetic

engineering of biological agents, to make them more

potent, has been carried out covertly for some years,

but not as an overt step to produce more effective

weapons. In genetic terms there are more similarities

between different people and peoples than there are

differences. But the differences exist, and may singly

or in combination distinguish the members of one social

group (an “ethnic” group) from another.

Research into the

development of specific treatments for many medical

conditions (both genetic and acquired) using genetic

knowledge and genetic techniques, is currently consuming

a significant proportion of the pharmacological research

budget internationally. This research considers

essentially the same molecular techniques as would

weapons development.

There are massive imbalances between states in the

availability and sophistication of weapons, both

conventional and nuclear. This is no reason for delaying

further the establishment of effective measures to

control the proliferation of biological weapons.

Processes to enhance and strengthen the existing

Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention are essential to

prevent the further spread of the current generation of

biological weapons. Effective monitoring and

verification procedures would also be powerful controls

against the development of genetically targeted

biological weapons.

Modern biotechnology and medicine have essential roles

in improving the quality of life for people in the

developed and developing world; molecular medicine has

much to offer people throughout the world. Procedures to

monitor against the abuse/malign use of this knowledge

and technology may also contribute significantly to the

development of effective disease surveillance programs.

‘Recipes’ for developing biological agents are freely

available on the Internet. As genetic manipulation

becomes a standard laboratory technique this information

is also likely to be widely available. The window of

opportunity for developing effective controls is thus

fairly narrow.

The medical profession has played a significant part in

the development of International Humanitarian Law,

especially through the International Committee of the

Red Cross (ICRC). The work of doctors with the ICRC on

the SIrUS project offers real hope of an extension of

this area of law to reduce the suffering which might be

caused by new weapons technology.

Realistically doctors should accept that even with

effective international legal instruments, some weapons

development with molecular biological knowledge will go

ahead. Doctors must therefore be prepared to recognize

and respond to the use of such weapons, and to advise

governments on plans and policies to minimize their

effect.

Urgent action is essential to ensure that the BTWC is

strengthened, and to reinforce the central concept that

biological weapons, whether simple or complex in design

and production, are wholly unacceptable.

The physician’s role is the prevention and treatment of

disease. The deliberate use of disease or chemical

toxins is directly contrary to the medical profession’s

whole ethos and rationale. Such misuse must be

stigmatized so that it is completely rejected by

civilized society.

There is a need for Government action at a national and

international level to complete effective, verifiable

and enforceable agreements and countermeasures before

the proliferation and development of new biological

weapons makes this almost impossible. Doctors and

scientists have an important role to play in campaigning

for, and enforcing, adequate preventive measures.

|

Rapid

Advances - How fast is fast?

Advancements in genome research have occurred at an amazing pace. The

U.S. Human Genome Project expects to complete the Human DNA Sequence

in the spring of 2003,27 two years ahead of the original

schedule.

RAFI's (now ETC Group's) Pat Roy

Mooney has written:

The amount of genetic information

being stored in the international gene banks is doubling every

14 months... A quarter century ago, it took a laboratory two

months to sequence 150 nucleotides (the molecular letters that

spell out a gene). Now, scientists can sequence 11 million

letters in a matter of hours.

The cost of DNA sequencing has

dropped from about US$100 per base pair in 1980 to less than a

dollar today [early 2001] and will be down to pennies by 2002.

Standard gene sequencing technology once required at least two

weeks and $US20,000 to screen a single patient for genetic

variations in 100,000 SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms).

Now 100,000 SNPs can be screened in a few hours for a few

hundred dollars.28

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs)

are small genetic variations that occur in individuals. But studies

are also being done by the SNP Consortium, an organization of

private biotechnology firms, 29 to see how they vary from

group to group.

The groups being studied are African

Americans, Asians and Caucasians.

Sequencing the

Human Genome: What do genes say about race?

The Human Genome Project has shown that 99.9% of human DNA is

identical throughout the species and that there are more genetic

variations within groups than between groups.30

Thus,

race, as we think of it socially, is a cultural construct, rather

than a genetic one.

Yet, our eyes tell us that there are differences. All humans would

look alike otherwise. It is also well known that certain ethnic

groups have predispositions to certain illnesses.

Something must account for those

predispositions.

-

Is that something in the 0.1% of

non-identical genes scattered throughout humanity?

-

More specifically, is that

something explained by Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms?

When it comes to the development of

"ethno bombs," it's the study of SNPs that most worries Edward

Hammond, director of the

Sunshine Project 31 and a

former RAFI staff member. It's the primary focus of the Sunshine

Project to prevent new breakthroughs in biotechnology from being

applied for military purposes.

In an interview with FTW in January,

2003, Hammond said of SNPs:

What these are, put in more simple

language, are little, small differences in the genetic code that

are in all of us, but ones which can be at least theoretically

related to a particular ethnic group or a particular kind of

people.

And so the fear is that these discoveries that there are

some very minor genetic differences that do seem to roughly

break down somewhat along culturally defined ethnic lines could

become exploitable, particularly once we reach the point where

genetic constructs that could be created by science could take

advantage of a group of these.

What I mean by that is that there

are very, very few genetic differences that in and of themselves

are markedly different from one population to another. However,

if you could do a combination of factors, a combination of small

differences in genes there might be ways to roughly create

something that you would call a genetic weapon.

If we arrive at the point where genetic weapons are possible,

and I do believe that this will happen, the thing that I'm most

concerned about are not the individual "disease" genes that have

been identified in the past. [Ethnically related genetic

disorders such as Cystic Fibrosis, Sickle Cell Anemia, or Tay-Sachs

Disease].

Rather it is a combination of genes

that occur in particular frequencies in different populations

and by targeting the absence or the presence of a particularly

small group of genes that seems to have some sort of ethnic

association, than by that way, I think genetic weapons may

become possible.

The rapid developments in genome mapping

have enabled the Human Genome Project 32 to meet all its

goals for 1994-1998, and to add two new goals for 1999-2003: the

determination of human sequence variation [mapping the SNPs] and

functional analysis of the operation of the whole genome

[understanding how the whole system works].

These are two goals vital to creating

ethnic-specific genetic weapons.33

Genetic

weapons development: terrorists won't try this at home

We cannot be sure how many states are trying to develop genetic

weapons. But we can be sure that the entities trying to develop them

are states (possibly with the help of large corporate contractors)

and not terrorist groups.

This is because only states can manage

the complex science genetic research requires. Dr. Claire Fraser,

President and Director of the Institute for Genomic Research (Tigr)

says that although genetic data on human pathogens are public, no

one knows enough to turn this information into bioweapons.

Speaking out against calls to classify

now public genome data, Fraser told BBC News Online:

"I want to debunk the myth that

genomics has delivered a fully annotated set of virulence and

pathogenicity genes to potential terrorists. I have heard some

describe genome databases as bioterror catalogues where one

could order an antibiotic-resistance gene from organism one, a

toxin from organism two, and a cell-adhesion molecule from

organism three, and quickly engineer a super pathogen, This just

isn't the case." 34

Of course, once states create these

weapons, it may be possible for terrorist groups to buy or steal

them.

Who's been

doing what?

Since all biological and chemical weapons are illegal, and since

ethnic weapons are especially abhorrent, countries doing research in

these areas don't brag about it. Nor do the corporate media take much

notice.

Number 16 on Project Censored's list of the 25 top

censored stories for the year 2001 was "Human

Genome Project Opens the Door to Ethnically Specific Bioweapons."

35

But in recent years, some information

has surfaced in government reports or corporate media indicating

that some countries have been researching the possibility of ethnic

weapons.

South

Africa: Apartheid regime sought "black bomb"

In the 1980s, South Africa's apartheid regime ran a biological

weapons program called "Project Coast".

According to an April 2001 U.S. Air

Force Report 36 one of the program's goals was to develop

a "black bomb" via genetic engineering research. The "black bomb"

would weaken or kill blacks but not whites.37

In addition to the "black bomb," Project Coast planned to build a

large-scale anthrax production facility to produce anthrax for use

against black guerrilla fighters inside or outside of South Africa

38, and to develop a drug that would induce infertility

and could be given surreptitiously to blacks, perhaps under the

pretext of a vaccine.39

None of these goals were achieved.

However, in one of the appendices to the

USAF report, the authors asked,

"In its genetic engineering

experiments, how close was South Africa to a 'black bomb'? Are

other countries developing similar biological weapons?" 40

Israel - CBW

program finds genetic differences between Arabs and Jews

On November 15, 1998, the Sunday Times of London ran a front

page article reporting that the Israelis were planning an ethnic

bomb.41

The article stated that the Israelis

were trying to identify distinctive genes carried by some Arabs,

particularly Iraqis.

"The intention is to use the ability

of viruses and certain bacteria to alter the DNA inside their

host's living cells. The scientists are trying to engineer

deadly microorganisms that attack only those bearing the

distinctive genes."

The article reported that the program

was based at

Nes Tziyona, Israel's main biological and chemical

weapons research facility, and that an unnamed scientist there said

that while the common Semitic origin of Arabs and Jews complicated

the task,

"They have, however, succeeded in

pinpointing a particular characteristic in the genetic profile

of certain Arab communities, particularly the Iraqi people."

The report also quoted Dedi Zucker,

a member of the Israeli Knesset (parliament) as saying,

"Morally, based on our history, and

our tradition and our experience, such a weapon is monstrous and

should be denied."

Israel has never signed the Biological

and Toxin Weapons Convention.42

The Human

Genome Diversity Project

The

HGDP is an international project based at the

Morrison Institute

for Population and Resource Studies at Stanford University in Palo

Alto, California.43

HGDP is not a part of the Human Genome

Project. The HGDP is of grave concern to people who believe

ethnically targeted genetic weapons are on the horizon. Among these

people is Dr. Barbara Hatch Rosenberg.

When asked by FTW via email if she was

concerned that the Human Genome Project and the Human Genome

Diversity Project will pave the way for genotype specific weapons,

she replied simply.

"Yes."

The FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions)

list of the HGDP does deal briefly with the issue of ethnic weapons:

Could these samples be used to

create biological weapons that were targeted at particular

populations?

Genocidal use of genetics is not possible with any currently

known technology. On the basis of what we know of human genetic

variation, it seems impossible that it will ever be developed.

The Project would condemn and bar any effort to use its data for

such purposes. The highly visible nature of the Project and its

ethical constraints should make even the attempt less plausible.44

This answer is unsatisfactory on a number of levels. First of

all, it was written in late 1993 and early 1994.45

Subsequent revelations have indicated that such weapons are

being attempted. That the Project would bar efforts to use its

data for such purposes is unenforceable. The Project is putting

its data in the public domain. How could it stop a government

from surreptitiously using that data? The "highly visible nature

of the Project and its ethical constraints" could make it

unlikely that members of the Project would use the data for

weapons development while they were members of the project. But

what would prevent them from doing so in subsequent research for

third parties?

Lastly the conclusion that "on the basis of what we know of

human genetic variation, it seems impossible that it will ever

be developed is likely premised on a false assumption that

Edward Hammond pointed out in his interview with FTW:

One of the things that people say is that,

'Well, look. You're never going

to be able to develop a genetic weapon that is perfect.

Whatever combination of genes or whatever gene you target,

is never going to have 100% occurrence in the population

that you target. And in almost all likelihood, your own

population is going to have that sequence.'

In other words, even in the "best

case scenario" of somebody who was evil enough to try to develop

this kind of weapon, it's never going to be perfect.

It's only going to get 70, 80% of

the enemy are going to potentially be subject to being affected

by this weapon and you might have 5, 10, 15% of your own people

potentially subject to this weapon. And so experts will say,

'You know, nobody's crazy enough to do that. Nobody would

actually do that because, think of the risk that would pose to

their own people. And think of the fact that it really isn't

going to work against all of the enemy.'

I really don't think that that kind of rationality pervades the

people that would potentially do this. And if you look at what

happens in ethnic conflicts, certainly rationality and

calculation about what ends you are willing to go to, to get the

other guy don't play out like that. So I think that there's a

certain willful ignoring of the reality of how conflict takes

place when people say that these aren't potentially practical

weapons.

In light of the Israeli research into the genetic differences

between Arabs and Jews, who share Semitic origin, and in light

of the overwhelming evidence that the United States Government

had foreknowledge of the 9-11 attacks and allowed them to occur,

resulting in the deaths of thousands of U.S. citizens, no one

should assume that any weapon, genetic or not, would not be

developed because some of the developer's people might suffer

the same fate as the targeted "enemy."

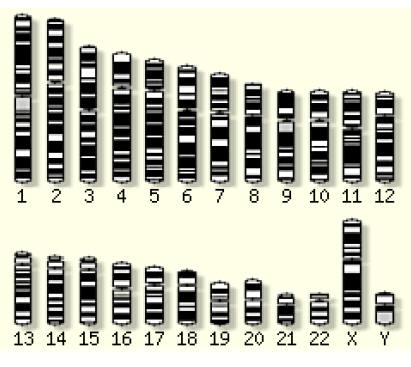

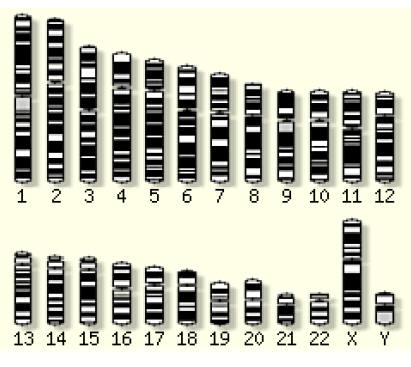

Human Chromosomes

Source:

http://www.ensembl.org

The U.S. and the

"dual use" dilemma: Treatments or weapons?

A genome is the complete DNA makeup of an organism, be it human,

animal or plant. Research on genomes could lead to greater

understanding of how disease pathogens or genetic defects operate.

This, in turn could lead to medical

breakthroughs: gene therapies, treatments that take into account the

individual genetically-based responses to medications, or treatments

for conditions for which certain population subgroups are

susceptible. For example, NitroMed, Inc., a private

biopharmaceutical company that is developing nitric oxide (NO)-

enhanced medicines, is testing a drug called BiDilTM,

which is designed to improve survival in African Americans with

heart failure.46

A trial involving 600 African American

men and women is now in progress, with the results expected in early

2004.47

But genome research, like many other forms of biological and

chemical research, is "dual use." And the U.S. Government appears to

be very interested in its military applications. Note that the

government's Joint Genome Institute (JGI) 48 is not under

the auspices of the Department of Health and Human Services. It is

part of the Department of Energy, which often works hand-in-glove

with the Defense Department.

DOE's own explanation for its involvement in the Human Genome

Project betrays military roots:

After the atomic bomb was developed

and used, the U.S. Congress charged DOE's predecessor agencies

(the Atomic Energy Commission and the Energy Research and

Development Administration) with studying and analyzing genome

structure, replication, damage, and repair and the consequences

of genetic mutations, especially those caused by radiation and

chemical by-products of energy production.

From these studies grew the

recognition that the best way to study these effects was to

analyze the entire human genome to obtain a reference sequence.

Planning began in 1986 for DOE's Human Genome Program and in

1987 for the National Institutes of Health's (NIH) program.

The DOE-NIH U.S. Human Genome

Project formally began October 1, 1990, after the first joint

5-year plan was written and a memorandum of understanding was

signed between the two organizations.49

The JGI web site describes the Institute

as "virtual human genome institute" that integrates the sequencing

activities of the human genome centers at the three JGI member

institutions:

JGI partner institutions include:

-

Oak

Ridge National Laboratory

-

Brookhaven National Laboratory

-

Pacific

Northwest National Laboratory

-

Stanford Genome Center 50

The Lawrence Livermore, Los

Alamos and Oak Ridge laboratories are well known as

nuclear weapons research facilities. Lawrence Livermore and Los

Alamos are seeking to install high containment microbiology labs in

their facilities.

These labs could work with virulent

organisms such as live anthrax, botulism, plague.

Opponents of biowarfare are concerned

that the United States is violating the Biological and Toxin Weapons

Convention by genetically modifying anthrax.51

ENDNOTES

1. (Crowley, Michael. Disease by

Design: De-Mystifiying the Biological Weapons Debate. Basic

Research Report, Basic Publications, http://www.basicint.org,

Number 2001.2 November 2001 Section 2)

2. (Ibid.)

3. (Ibid.).

4. (Ibid.)

5. (a copy is available at at the web site of the Stockholm

International Peace Research Institute, http://projects.sipri.se/cbw/docs/bw-btwc-texts.html)

6. (Rosenberg, Prof. Barbara Hatch, "Defending Against

Biodefence: The Need for Limits," p.1 http://www.fas.org/bwc/papers/defending.pdf)

7. (a list of signatories is available at http://projects.sipri.se/cbw/docs/bw-btwc-sig.html)

8. (Ibid.)

9. (a list of ratifications is at http://projects.sipri.se/cbw/docs/bw-btwc-rat.html)

10. (http://projects.sipri.se/cbw/docs/bw-btwc-nonsig.html).

11. (Dr. Ken Alibek, the head of the then-Soviet Union's

biological warfare program, Biopreparat, described the Soviet

Union's offensive weapons development in a PBS Frontline program

called "Plague War" which aired on 10.13.1998. The transcript of

Frontline's entire interview with Alibek is at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/plague/interviews/alibekov.html).

12. (Cohen, William S., "Proliferation: Threat and Response,"

U.S. Department of Defense, 1997, http://www.defenselink.mil/pubs/prolif97/)

13. (Mooney, Pat Roy, "Technological Transformation: The

Increase in Power and Complexity is Coming just as the 'Raw

Materials' are Eroding" The ETC Century - Development Dialogue

1999:1-2 Dag Hammarskjold Foundation, Uppsala Sweden, p. 33

http://www.dhf.uu.se)

14. (Ibid.)

15. (Ibid.)

16. (see Section 5 of The National Security Strategy of the

United States of America at http://www.whitehouse.gov/nsc/nss5.html,

and The National Strategy to Combat Weapons of Mass Destruction

at http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2002/12/WMDStrategy.pdf)

17. (http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/plague/interviews/cohen.html)

18. (Cohen, William S., "The Report of the Quadrennial Defense

Review," U.S. Department of Defense, May 1997. http://www.defenselink.mil/pubs/qdr/).

19. (Rosenberg, op.cit. p. 3)

20. (Ibid.)

21. (http://www.etcgroup.org)

22. (Mooney, op.cit. p. 34).

23. (Ibid. p. 34)

24. (The Genetics Forum, "Genetic Weapons Threat?" The Splice of

Life, Vol. 3 No. 4, February 1997. http://www.geneticsforum.org.uk/warfare.htm)

25. (Harwood Academic Publishers, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1999)

26. (http://www.bma.org.uk/ap.nsf/Content/Biotechnology%2C+weapons+and+humanity+-%28m%29?OpenDocument&Highlight=2,biotechnology)

27. (U.S. Human Genome Project Five-Year Research Goals,

1998-2003,. http://www.ornl.gov/TechResources/Human_Genome/hg5yp/)

28. (Mooney, op. cit. pp. 25-26).

29. (http://snp.cshl.org/ The member companies are: AP Biotech,

AstraZeneca, Aventis, Bayer, Bristol-Meyers Squib,

F.Hoffman-LaRoche, Glaxo Wellcome, IBM, Motorola, Novartis,

Pfizer, Searle, SmithKline Beecham, and Wellcome Trust)

30. (Aidi, Hisham, "Race and the Human Genome," http://www.africana.com/DailyArticles/index_20010129.htm).

31. (www.sunshine-project.org)

32. (http://www.ornl.gov/hgmis/)

33. (Dando, Malcolm, Appendix 13A. "Benefits and threats of

developments in biotechnology and genetic engineering," SIPRI

Yearbook 1999: Armaments, Disarmament and International

Security, Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1999, pp. 2-3.)

34. (Whitehouse, Dr. David, "DNA databases 'no use to

terrorists,' BBC News Online January 15, 2003, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/2660753.stm)

35. (http://www.projectcensored.org/stories/2001/16.html).

36. (Burgess, Dr. Stephen F. and Purkitt, Dr. Helen E., "The

Rollback of South Africa's Chemical and Biological Warfare

Program," USAF Counterproliferation Center, Air War College, Air

University, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama, April 2001, http://www.au.af.mil/au/awcgate/awc-cps.htm)

37. (Ibid. p.21 and p.105 n60).

38. (Ibid. p. 21)

39. (Ibid. p. 105 n62).

40. (Ibid. p. 84, n17)

41. (Mahnaimi, Uzi and Colvin, Marie, "The Israelis are making a

virus that will target Arabs: Israel planning 'ethnic' bomb as

Saddam caves in", London Times, November 15, 1998).

42. (http://projects.sipri.se/cbw/docs/bw-btwc-nonsig.html).

43. (www.stanford.edu/group/morrinst/hgdp.html)

44. (http://www.stanford.edu/group/morrinst/hgdp/faq.html#Q12)

45. (http://www.stanford.edu/group/morrinst/hgdp/faq.html).

46. (Press Release: NitroMed and Merck Form Strategic

Collaboration, January 7, 2003, http://www.nitromed.com/press/01-07-03.htm)

47. (Ibid.)

48. (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/)

49. (The Department of Energy and the Human Genome Project Fact

Sheet, http://www.ornl.gov/hgmis/project/whydoe.html)

50. (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/whoweare/members.html)

51. (Ramares, Kellia, "As Bush threatens Iraq with nukes, US

ramps up its own biowarfare research",

http://www.rise4news.net/ramp.html ).

PART 2

March 11, 2003

|

In the conclusion of her

two-part series on gene-specific bioweapons Kellia

Ramares reveals an easily overlooked truth.

The most likely and

easiest targets of such weapons are food crops and

livestock which would provide the attacking nation with

a degree of deniability.

Then, in her conclusion

Ramares states two facts that are probably all too

obvious.

Of all the nations in the

world the U.S. is the most likely to develop such

weapons and history and that human nature teach us to

expect them, and soon. – MCR |

TALKING ABOUT ETHNIC

WEAPONS - NOT IN POLITE COMPANY

The web sites for Human Genome Project Information are

maintained on the web site of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory.52

Part of the web site is devoted to information on Ethical, Legal and

Social Issues.53

That page stated that,

"The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)

and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have devoted 3% to

5% of their annual Human Genome Project (HGP) budgets toward

studying the ethical, legal, and social issues (ELSI)

surrounding availability of genetic information. This represents

the world's largest bioethics program, which has become a model

for ELSI programs around the world." 54

The issues raised on that page were:

-

fairness in the use of genetic

information by insurers, employers, courts, schools,

adoption agencies, and the military, among others

-

privacy and confidentiality of

genetic information

-

psychological impact and

stigmatization due to an individual's genetic differences

-

reproductive issues including

adequate informed consent for complex and potentially

controversial procedures, use of genetic information in

reproductive decision making, and reproductive rights

-

clinical issues

-

uncertainties associated with

gene tests for susceptibilities and complex conditions

-

conceptual and philosophical

implications regarding human responsibility, free will vs.

genetic determinism, and concepts of health and disease

-

health and environmental issues

concerning genetically modified foods (GM) and microbes

-

commercialization of products

including property rights (patents, copyrights, and trade

secrets) and accessibility of data and materials.55

This page contains no mention of

military applications of genetics, or the possible development of

ethnic weapons.

Likewise, the page that is devoted to Minorities, Race, and Genomics

56 contained information about conferences for minority

leaders to inform them about the benefits of genetic research, and

to discuss ways of helping more minority group members to develop

careers in genetics.

Issues that would be of primary interest

to minority group individuals, i.e. genetic testing, use of genetics

in the courtroom, patenting and other business issues, and careers

in genetics were the subjects of the conferences. But the issue of

interest to the continued survival of minority groups, i.e. the

development of gene-specific ethnic weapons, was not on the agenda.

Howard University, perhaps the most prestigious of the historically

black colleges and universities in the United States, has a National

Human Genome Center.57 The formation of the Center was announced on

May 1, 2001.

Its mission is,

"to explore the science of and teach

the knowledge about DNA sequence variation and its interaction

with the environment in the causality, prevention, and treatment

of diseases common in African American and other African

Diaspora populations." 58

The program contains an ethics unit (GenEthics),

which will be a source of bioethics information for the University

and larger community as a whole. But again, military applications of

genetics, and the implications of those applications for minorities

is not mentioned among the many aspects of ethics with which the

GenEthics unit will concern itself.

Of course, this is not to say that any attendees of the minority

conferences or the participants in the Howard University National

Human Genome Center or any other human genome research facility

in the world never discuss or research the ethical implications of

genetic weapons. But the lack of open acknowledgement of the topic

is disturbing.

It is also not surprising to Edward

Hammond of the Sunshine Project.

He told FTW:

"Genetically targeted weapons or

ethnic weapons are a big No-No to talk about in the world of

biological weapons control. You don’t do it because you get

scoffed at the minute that you do it. I personally think that

people are sticking their heads in the sand about it."

AGRO-TERRORISM: THE LIKELY FIRST CASE SCENARIO

The first genetic weapons are likely to be aimed, not at humans, but

at agriculture.

This is because so much more is known

about plant and animal genetics through years of work sequencing

their genomes and because modern agriculture has developed

genetically uniform crops, which could be more easily attacked than

people. Agricultural genetic weapons could also have a similar

effect on a people as a direct genetic weapon, by wiping out many of

the food sources of a geographically concentrated ethnic group.

Dr. Mark Wheelis, a microbial biochemist and geneticist at

the University of California Davis, focuses his research on the

history of biological warfare, and on biological weapons control. He

sees anti-agricultural bioweapons as being within the reach, not

only of states, but also of agricultural corporations, organized

crime, terrorist groups and individuals.59

According to Wheelis, reasons to attack agriculture would include:

attacking the food supply of an enemy belligerent; destabilizing a

government by initiating food shortages or unemployment; altering

supply and demand patterns for a commodity, or commodity futures,

and for other manipulations and disruptions of trade and financial

markets.60

An agricultural bioattack would be easier to carry out than one

directly against humans because there are many plant and animal

diseases that humans could disperse without harming themselves by

handling the bioagents. Fields have little or no security. If the

goal is an economic one, such as to disrupt trade, the creation of

only a few cases may be necessary to require the quarantine or

destruction of a region’s crops or animals.61

One example of the havoc an agricultural

disease can wreak on farm economies occurred in England in 2001,

when over the course of 9 months, 5.7 million animals were

slaughtered at a cost of 2.7 billion pounds after an outbreak of

foot and mouth disease.62

Terminator

Technology - a gateway to genetic attacks on agriculture?

Terminator Technology, developed by St. Louis-based

Monsanto Corporation, is the rubric

for any of several patented processes of genetic engineering for the

"control of plant gene expression," that result in second generation

seeds "committing suicide" by self poisoning when an outside

stimulus, most often the anti-biotic tetracycline, is applied to the

crop.63

The goal of Terminator is to destroy the millennia old practice of

seed-saving, thus forcing farmers to buy new seed in the market each

year. Not surprisingly, Monsanto has been busy buying up seed

companies.

As of 1998, Monsanto owned Holdens

Foundation Seeds, supplier for 25-30% of US maize acreage,

Asgrow Agronmics, the leading soybean distributor in the US, De

Kalb Genetics, the second largest seed company in the US and the

ninth largest in the world, and Delta and Pine Land Company.64

This latter acquisition has given Monsanto control of 85% of the

U.S. cotton seed market.65

Though technically not a genetic weapon as we have defined such in

this article, Terminator technology and corporate monopolies on seed

development and distribution can make the world more vulnerable to

gene-specific attacks on crops by proliferating genetically

identical plants.

In an interview with FTW in January 2003, Dr. Wheelis said:

Since plant varieties are

particularly highly inbred, and many domestic animals are very

highly inbred, although not to the extent that many plants are,

this does mean that, unlike humans, where there is a tremendous

heterogeneity in any population, there’s a very high degree of

genetic homogeneity.

So you can travel for a hundred

miles in [the] Midwest and see thousands of square miles planted

with exactly the same variety of maize. And that means, using

what one knows of the maize genome, and of this particular

variety of maize, it might be possible to develop a chemical

agent that will affect one variety of maize, but not another. Or

a particular virus might be able to be engineered so it is able

to infect on particular strain of maize or rice or whatever, but

not others.

And so this does raise at least the

theoretical possibility, that one could tailor chemical or

biological weapons to attack varieties of domestic crops or

animals that were used in certain parts of the world and yet

these chemicals or infectious agents would be harmless or much

less harmful to other varieties.

FTW: Then...the mere fact that there are companies out

there looking to spread a particular strain or species of maize,

rice, whatever, and really the doing in of indigenous or

farmer-developed crop could actually make it easier for genomic

weapons?

Wheelis: Yes, for sure. One of the most robust defenses

against genotype specific weapons is a considerable amount of

genetic heterogeneity. And in many parts of the developing world

there are many different varieties of crops, often grown very

close to each other. So you can find different land races of

maize, for instance, in Mexico, grown only a few kilometers

apart.

Yet they’re remarkably different

strains of maize. And so that kind of genetic heterogeneity in

which over a large geographic area there are many different

varieties of the same crop, sometimes several varieties

cultivated together on the same plot of land, makes those crops

quite resistant to any kind of genetic specificity of a weapon.

In contrast, in the developed world, we commonly plant very

large acreages, at very high densities, of identical, not just

similar, but identical genotypes of whatever crop we’re talking

about.

And so that makes this high density,

low genetic diversity monoculture quite vulnerable to this kind

of attack, whereas the lower density, intercropped, genetically

variable agriculture of much of the developing world is not so

susceptible to this.

Thus, ironically, it is the United

States, a major agricultural producer, and the world’s biotech

leader and superpower that could be devastated by a genetically

specific agricultural bioattack.

But Monsanto is also targeting the developing world.

Dr. Harry B. Collins, Vice

President for Technology Transfer at Delta and Pine Land

Co., now owned by Monsanto, said in 1998,

"The centuries old practice of

farmer-saved seed is really a gross disadvantage to Third World

farmers who inadvertently become locked into obsolete varieties

because of their taking the 'easy road' and not planting newer,

more productive varieties." 66

Modern chemical dependent farming is

anything but an "easy road" for farmers of the developing world.

Dependence on chemical inputs has raised the cost of farming in the

Global South with devastating consequences.

Radiojournalist Sputnik

Kilambi has covered the suicides of farmers in India:

Between 1997 and the end of 2000, in

just the single district of Anantapur in Andhra Pradesh, 1,826

people, mainly farmers, committed suicide. Most of the deaths

were debt-related. Rising input costs, falling grain and oil

seed prices, closures by banks, all policy-driven measures,

crushed them... Small and marginal farmers of Anantapur have

no other option.

The region is a monocrop area and

suffers from inadequate irrigation... Ironically, says K. Gopal,

it is the younger farmers, who in principle are open to

modernization, that are most liable to commit suicide.

"They’re very enterprising,

risk-taking farmers. They’re willing to go in for modern

agricultural practices, with a view to increase ease, to

increase profitability. They go in for modern agricultural

practices; they even go in for the use of insecticides, for

the use of good quality seeds.

What this shows is that modern

farming does not have any validity for the small and

marginal farmer kind of situation in which we are faced. The

technology is not relevant; the profitability is not

relevant; the liability is not valid."

For K. Gopal it is clear that the

Andhra Pradesh government wants the farmers to get out of

farming, to make way for the brave new world of corporate and

industrialized farming. The Israelis have set up such a model in

[an] area where the farmers grow exotic items like gerkins and

baby corn for the urban middle and upper classes.

The old

relationship between farmer and land has been totally

destroyed...67

Corporate farming is doomed to failure

as the End of the Age of Oil makes the petrochemically-derived

pesticides and fertilizers on which it is dependent uneconomical

and, inevitably, unavailable.

But if, in the meantime, indigenous

farmers and farming practices, including seed saving and cultivating

genetically diverse crops, are destroyed, we may not need to develop

"ethno-bombs" to destroy the only race genome researchers say there

is: the human race.

Conclusion:

It's not the knowledge; it's what we do with it

With genetic research having a potential for beneficial use, the

question is not whether to conduct the research, but how and to what

end. The "how" is extremely important to indigenous and other

minority populations who have been exploited by white Western

science for centuries.

On February 19, 1995, representatives of

17 indigenous organizations meeting in Phoenix, Arizona, issued a

"Declaration of Indigenous Peoples of the Western Hemisphere

Regarding the Human Genome Diversity Project." 68

The document opposes the Human Genome

Diversity Project, condemns the patenting of genetic materials

and demands,

"an immediate moratorium on

collections and/or patenting of genetic materials from

indigenous persons and communities by any scientific project,

health organization governments, Independent agencies, or

individual researchers." 69

The document reaffirmed,

"that indigenous peoples have the

fundamental rights to deny access to, refuse to participate in,

or to allow removal or appropriation by external scientific

projects of any genetic materials." 70

Indigenous concerns are well founded,

especially in light of the shameful history of white scientific

practice that has indigenous people still struggling to reclaim

sacred artifacts and the very bones of their ancestors from museum

shelves.

But even this document, so strongly opposed to genetic research on

indigenous people, sounds a contradictory note.

"We demand that scientific endeavors

and resources be prioritized to support and improve social,

economic and environmental conditions of indigenous peoples in

their environments, thereby improving health conditions and

raising the overall quality of life."

Among the Pima Indians of Arizona, for

example, 50% of people between the ages of 30 and 64 have diabetes.71

What if genetic research could find the cause and even a treatment

for the high incidence of diabetes among American Indians and Alaska

Natives?

The question "To what end?" concerns us all. What if Israel, which

apparently is researching genetic difference between Jews and Arabs

to develop an ethnic weapon, altered its foreign policy to embrace

the genetic research that links the two peoples? 72

The U.S. Department of Energy is doing research within the Human

Genome Project on chromosomes 5, 16 and 19.

DOE says,

"Particular genes of interest are

those mediating individual susceptibilities to environmental

toxins and ionizing radiation." 73

Is DOE looking to refine dosage levels

for radiation treatments for cancer, or is it trying to figure out

how many people will survive strikes with tactical nuclear weapons?

Even a cursory survey of the scientific literature in genetics

indicates scientific interest in the genetic differences within and

between peoples. In addition to possible medical applications of

this research, there are other intriguing questions, about

historical human migration patterns and the distribution and

relationships of languages, for example, which should be of no

military interest.

But research that does turn up

differences in the genetics of socially defined ethic groups is open

to abuse, in all likelihood by governments, even if the scientists

doing that research intended no such thing. The way to prevent such

abuse is to strengthen the moral repugnance biological, chemical and

genetic weapons and to create legal means to enforce the

Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention and the Chemical

Weapons Convention.

Right now, the political and ethical

dialogues are simply not keeping up with the pace of scientific

advancements in genome research.

Dr. Wheelis of U.C. Davis says:

[M]y sense is that the United

States, some time ago, decided that chemical and biological

weapons, and possibly even nuclear weapons were going to be

proliferating worldwide. And that current arms control regimes

had been unsuccessful in preventing that and that additional

international negotiations didn’t look to hold out much hope for

actually restraining weapons proliferation.

Now I personally disagree with that.

But I think that’s the position that many in the United States

government have come to. They’ve concluded that there’s clear

evidence of chemical and biological weapons proliferation in the

world. That the biological weapons convention, the chemical

weapons convention haven’t prevented that, that protocol for the

biological weapons convention didn’t seem to have much promise

to them as a tool to increase the safeguards against

proliferation.

And so I think the United States is

in more of a responsive than a preventative mode. I think we

basically decided prevention of proliferation has failed; it’s

going to happen anyway; there’s not much we can do about it. And

so we should go into a mode in which we respond." 74

But the conventions have no teeth

because the United States keeps resisting all efforts to give them

any. Dr. Barbara Hatch Rosenberg has written:

Since the BWC came into force in 1975, biotechnology has progressed

rapidly, its military potential has not gone unnoticed, and

suspicions have multiplied. Anxious to increase transparency and

ensure compliance with the Convention, the state parties in 1986

adopted an annual information exchange as a Confidence Building

Measure (CBM).

The ineffectiveness of this

'politically-binding' measure led the parties in 1991 to initiate

the process of developing a legally-binding Protocol to monitor

compliance. Ten years later this process became stalemated over the

implacable opposition of the Bush Administration to any

legally-binding instrument.75

If the United States will not legally commit itself to compliance

with the Convention, on what legal, moral, or rational basis can it

go to war against Iraq or any other nation claiming that the other

nation is creating chemical or biological weapons?

ENDNOTES

52. (www.ornl.gov/hgmis).

53. (http://www.ornl.gov/hgmis/elsi/elsi.html).

54. (Ibid.)

55. (Ibid.)

56. (http://www.ornl.gov/hgmis/elsi/minorities.html)

57. (http://www.genomecenter.howard.edu/intro.htm)

58. (Ibid.)

59. (Wheelis, Dr. Mark, "Agricultural Biowarfare and

Bioterrorism," Edmonds Institute Occasional Paper, 2000).

60. (Ibid.)

61. (Ibid.)

62. (Chrisafis, Angelique, "Devastation in the wake of foot and

mouth: Farmers count epidemic's cost as last 'infected status'

areas are downgraded." The Guardian, December 1, 2001)

63. (Steinbrecher, Ricarda A, and Mooney, Pat Roy, "Terminator

Technology: The Threat to World Food Security," The Ecologist,

Vol. 8 No. 5, September/October 1998, p. 277).

64. (Tokar, Brian. "Monsanto: A Checkered History," The

Ecologist, Vol. 8 No. 5, September/October 1998, p. 259)

65. (Ibid.)

66. (Steinbrecher and Mooney, op.cit. p. 277)

67. (Kilambi, Sputnik, "Thousands of farmers commit suicide in

India," Free Speech Radio News, December 27, 2001).

68. (http://www.indians.org/welker/genome.htm).

69. (Ibid.)

70. (Ibid.)

71. ("Diabetes in American Indians and Alaska Natives Fact Sheet

," National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse, National

Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH

Publication No. 99-4551, April 1999.)

72. (Larkin, Marilynn. "Jewish-Arab affinities are gene-deep."

Lancet. 355 (2000); Kraft, Dina. "Palestinians, Jews Linked in

Gene Study."Chicago Sun Times. 10 May 2000, late sports final

ed.: 39.; Hammer, M.F., et al. "Jewish and Middle Eastern

non-Jewish Populations Share a Common Pool of Y Chromosome

Biallelic Haplotypes." Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences. 97 (2000): 6769-74. These are among many articles,

mostly scientific, on the subject of genetics and identity at

http://www.bioethics.umn.edu/genetics_and_identity/biblio.html)

73. (U.S. Department of Energy, "Research Abstracts from the DOE

Genome Contractor-Grantee Workshop IX " January 27-31, 2002

Oakland, CA. http://www.ornl.gov/hgmis/publicat/02santa/index.html)

74. (Phone interview, January 2003)

75. (Rosenberg, op.cit. p. 1).

|