|

by Stephanie Rogers from EarthFirst Website

It’s a scary thought for most of us, but for

T. Boone Pickens, it’s a dream he’s banking on.

His plan was to build a pipeline from the

aquifer to larger cities, selling the water as a commodity that, at least in

his mind, would undoubtedly be in demand during times of drought.

So when it was time to vote on allowing the

creation of Pickens’ water district, the only people required to vote on it

were the people who live on the land: Pickens, his wife and three employees.

Pickens was recently in the news for spending big bucks on wind farms.

His move toward investing in alternative energy doesn’t mean he’s an environmental activist, though: he’s in it for the money. While there’s nothing wrong with businesses making profits off products, policies and practices that are beneficial to the environment, Pickens’ past and present ventures make it clear he’s no friend to the earth.

In fact, he’s admitted that he’s taking

advantage of public fears about climate change, and he’s obviously not too

concerned about the environmental impact of draining

the Ogallala Aquifer.

Annual withdrawal from this aquifer is already outpacing the recharge rate by 300%. The amount of groundwater in the aquifer has been steadily declining in recent years. The government also faces a hurdle that billionaires with access to oil might be able to jump more easily: the rising cost of energy needed to pump water from the aquifer is making it tougher to access it.

The USDA laments that,

Undoubtedly, a public water crisis is brewing.

While other countries have been suffering a lack of water for years, America has remained largely insulated from the problem. We’re only beginning to experience the effects of a water shortage, partially due to unscrupulous deals made by bottling companies like Nestle along with America’s dependence on bottled water.

The more people buy bottled water, the less

money goes into the public water system. Corporations with dollar sign

fairies dancing in their minds see it as an opportunity to grab and wield

control over the supply. In a country dominated by a ‘winner takes all’

capitalist attitude, that sets us up for trouble.

Obviously, we can’t live without water. We’d be

at the mercy of the people in control.

Right now, only 5 percent of the water supply is

in corporate hands, but that could change at any time, especially as the

World Bank and other organizations push for privatization.

The Sierra Club is one of them, and their efforts to educate the public in Texas might just pay off. Until the day that Texas gets so dry officials are desperate for water and willing to do just about anything to get it, that is. Then a ball may be set in motion that will change public water access as we know it.

We can only hope that other solutions are put

forth before that becomes a reality.

by Susan Berfield from BusinessWeek Website

Pickens hopes to run a water pipeline over 250 miles and 650 tracts of private property from the Texas Panhandle

to thirsty

Dallas Nancy Newberry

Roberts County is a neat square in a remote corner of the Texas Panhandle, a land of rolling hills, tall grass, oak trees, mesquite, and cattle. It has a desolate beauty, a striking sparseness.

The county encompasses 924 square miles and is home to fewer than 900 people.

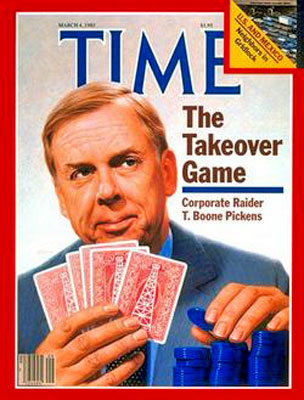

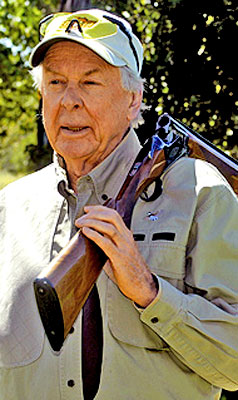

One of them is T. Boone Pickens, the oilman and corporate raider, who first bought some property here in 1971 to hunt quail.

He's now the largest landowner in the county: His Mesa Vista ranch sprawls

across some 68,000 acres. Pickens has also bought up the rights to a

considerable amount of water that lies below this part of the High Plains in

a vast aquifer that came into existence millions of years ago.

Pickens owns more water than any other individual in the U.S. and is looking to control even more. He hopes to sell the water he already has, some 65 billion gallons a year, to Dallas, transporting it over 250 miles, 11 counties, and about 650 tracts of private property. The electricity generated by an enormous wind farm he is setting up in the Panhandle would also flow along that corridor.

As far as Pickens is concerned, he could be selling wind, water, natural gas, or uranium; it's all a matter of supply and demand.

In the coming decades, as growing numbers of people live in urban areas and climate change makes some regions much more prone to drought, water - or what many are calling "blue gold" - will become an increasingly scarce resource.

By 2030 nearly half of the world's population will inhabit areas with severe water stress, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation & Development. Pickens understands that. And while Texas is unusually lax in its laws about pumping groundwater, the rush to control water resources is gathering speed around the planet.

In Australia, now in the sixth year of a drought, brokers in urban areas are buying up water rights from farmers. Rural residents around the U.S. are trying to sell their land (and water) to multi- national water bottlers like Nestlé (BW - Apr. 14).

Companies that

use large quantities of the precious resource to run their businesses are

seeking to lock up water supplies. One is Royal Dutch Shell, which is buying

groundwater rights in Colorado as it prepares to drill for oil in the shale

deposits there.

But like many others, Pickens believes there's a fortune to be made in slaking the thirst of a rapidly growing population.

If he pumps as much as he can, he could sell about $165 million worth of water to Dallas each year.

in 2003 David Bowser/Black Star

He started as a wildcatter in 1956; three decades later his Mesa Petroleum was the largest independent exploration company in the U.S. But that's not how Pickens made a name for himself - it was his hostile bids, one after the other through the 1980s, for oil companies far more powerful, far wealthier than his own.

Pickens thought they could do more for their shareholders.

He never took over any of them. He did, however,

push them into deals they might not have considered otherwise, which helped

reshape the oil industry.

It was in the midst of this that he acquired a

newfound regard for water as a commodity that should be bought, sold, and

traded for the benefit of those who own it and those who can afford it.

That Roberts County would become the stomping ground for the Panhandle water wars was perhaps inevitable.

Underneath it lies one of the world's largest repositories of water, moving slowly among layers of gravel, sand, and silt. The Ogallala Aquifer stretches from Texas to South Dakota and contains a quadrillion gallons of water - enough to cover the U.S. mainland to a depth of almost two feet.

Yet the extensive irrigation necessary to grow

corn, cotton, and wheat in west Texas has left the Ogallala nearly depleted

in some places. It is not an aquifer that is easily or quickly replenished.

But the land in Roberts County is unsuited for agriculture, and so the

Ogallala there is largely untapped.

This put Pickens in an uncomfortable position: If he didn't sell his water to CRMWA, the utility could potentially suck some of it right out from under his ranch.

So he tried.

Kent Satterwhite, who was then assistant general manager, says:

That was the first of several contretemps between Pickens and various local water authorities. Pickens next approached the city of Amarillo, which also had begun to acquire water rights in Roberts County.

It wasn't interested, either, though it did purchase water from several other nearby landowners.

When Amarillo turned him down, Pickens felt surrounded.

Pickens decided to fight.

In 1999 he created a company called Mesa Water

and began to accumulate water rights so he could strike a deal with another

city altogether. The hell with Amarillo. Pickens was confident he could sell

his water: The population of Texas was expected to jump 40% by 2020, mostly

in urban areas one dry season away from drought.

Pickens says he's buying stranded, surplus water that needs to be rescued.

Kim Flowers, who runs an 8,300-acre ranch in Roberts County, speaks for many landowners when she says:

In all, Pickens, CRMWA, and Amarillo have spent about $150 million to buy up nearly 80% of the water rights in Roberts County, undermining and outbidding one another along the way.

One unsurprising effect of their competition is that the price of an acre of water has in some places doubled, to $600. That's something in which Pickens takes pride. Much as he did in the 1980s, when he went after big oil companies he believed weren't doing right by their shareholders, Pickens now talks about creating value for Roberts County landowners.

They make money from selling their water while continuing to live, run cattle, and hunt on their property.

Not all Roberts County landowners wanted to do business with him, though.

Pickens intended to pull water from an aquifer that is pretty much the sole source for the Panhandle, and that isn't refilled quickly, and sell it to a place like Dallas, whose water use is the highest of any city in Texas. This seemed ludicrous, even reckless, to some.

C.E. Williams runs the Panhandle Groundwater Conservation District, which is responsible for managing the competing demands on the region's share of the Ogallala.

He puts it this way:

Pickens has a way of dismissing the complexity of a situation, sometimes even the possibility of an opinion contrary to his own.

In this case, any opposition to his plan from anyone who is not a Roberts County landowner, who is not essentially a shareholder in this venture, he deems irrelevant.

Williams, he points out, doesn't himself have any property.

When it comes to potential buyers, Pickens cares about only one thing: how much they're willing to pay.

Republican State Representative Warren Chisum is a Roberts County rancher who owns 12,000 acres next to Pickens and sold his water to Amarillo in 2001. He would seem to be a natural ally.

He's not.

In 2002, Pickens began approaching several of Texas' sprawling cities, all of which share one defining feature:

But with water, as with so much else, location is critical.

And Pickens' water is far, far away from anyplace that might buy it. Pickens knew he'd have to build a pipeline, and to do so at anything resembling a reasonable cost, he'd need the power of eminent domain - the right of a government entity to force the sale of private property for the public good.

Water utilities have that right. If Dallas

agreed to buy Pickens' water, it could extend such authority to him. But

Dallas deemed Pickens' price too high and declined to do a deal. So Pickens

and his executives tried to create a Fresh Water Supply District - a

government entity that would have that power. But they couldn't get it

through.

And since, one day anyway, Dallas may well buy

both, Mesa could use a single right-of-way for the water pipeline and the

electric lines.

It had been a decade since Pickens first realized the potential value of the water deposited eons ago in the sand below the High Plains. Now it was time to employ the one resource he hadn't yet used: his lobbying clout.

The 80th session turned out to be very productive, and one person who kept busy during that time was J.E. Buster Brown, a former state senator and one of the most powerful lobbyists in town.

Among Brown's clients is Mesa Water.

Brown did more than that: He helped win Pickens a key new legal right. It was contained in an amendment to a major piece of water legislation.

The amendment, one of more than 100 added after the bill had been reviewed in the House, allowed a water-supply district to transmit alternative energy and transport water in a single corridor, or right-of-way.

After the bill passed, Tom "Smitty" Smith, Texas director of Public Citizens, an advocacy group, says several legislators were drinking coffee and reading through it.

They'd just realized the amendment would help Pickens build his pipeline.

State Senator Robert Duncan, a Republican who represents Lubbock, says:

Pickens still needed the power of eminent domain if he was going to build his pipeline and wind-power lines across private land.

And by happy coincidence, the legislators passed a smaller bill that made that all the easier. The new legislation loosened the requirements for creating a water district. Previously, a district's five elected supervisors needed to be registered voters living within the boundaries of the district. Now, they only had to own land in the district; they could live and vote wherever.

The bill, as it happens, was put forth by two legislators from Houston; Brown says he and Mesa had nothing to do with it.

Pickens moved quickly to take advantage of the new rules.

Over the summer of 2007, he sold eight acres on the back side of his ranch to five people in his employ: Stillwell, who resides in Houston, two of his executives in Dallas, and the couple who manage his ranch, Alton and Lu Boone. A few days later, Mesa Water filed a petition to create an eight-acre water-supply district with those five as the directors and sole members.

On Nov. 6, Roberts County held an election to

decide whether to form the new district. Only two people were qualified to

take part: Alton and Lu Boone. The vote was unanimous. With that, Pickens

won the right to issue tax-free bonds for his pipeline and electrical lines

as well as the extraordinary power to claim land across swaths of the state.

As for the suggestion that he wouldn't have qualified to be a board member under the old rules, Stillwell says:

In April, 2008, Mesa sent out some 1,100 letters

to people along the 250-mile proposed right-of-way, from Miami, Tex., to a

town called Jacksboro, just short of Dallas. The letters included a Texas

landowners' bill of rights, information on the condemnation procedure, a map

of the route, and a list of open houses they could attend for more

information.

When the ranchers arrived, more than a dozen of Mesa's public-relations consultants, hydrologists, and land men were waiting for them. Standing behind tables laid out with pens, cups, hats, and bags with the District No. 1 logo, the officials were available to answer questions about the 250-foot-wide corridor Mesa would use to construct, maintain, and possibly expand the pipeline and electric lines.

While this arrangement allowed everyone to get information specific to their property, it also precluded any public questioning of the Mesa standard-bearers.

This did not go unnoticed by the ranchers.

Another said:

At the end of the evening, most of the pens and

hats and cups still lay on the tables.

Mesa expects to acquire the land it needs in the next 18 months and pay about $30 million for it; Pickens wants to begin construction on the $1.2 billion pipeline right afterward. It should take about three years to complete.

If all goes according to plan, Mesa will be able

to pump enough water to satisfy the needs of some 1.5 million Texans every

day.

So far, though, the talks might best be characterized as preliminary.

Rickman says that at some point he would have to consider the consequences for the Ogallala:

In Roberts County, people hold on to the hope that pumping from the Ogallala can be controlled.

In 1998, as Pickens and local water utilities began buying up water rights, the groundwater conservation district placed some restrictions on the rule of capture that it calls the 50-50 rule: Anyone who receives a new permit to pump can draw down the aquifer by only 50% over the next 50 years. Later, an additional limit of 1.2% per year was set.

These essentially manage the depletion of the Ogallala under Roberts County; there, it is replenished at a rate of only 0.1% a year. Williams, who put the rules into place, says:

Pickens has promised to abide by the 50-50 rule.

|