|

from

ZDNet Website

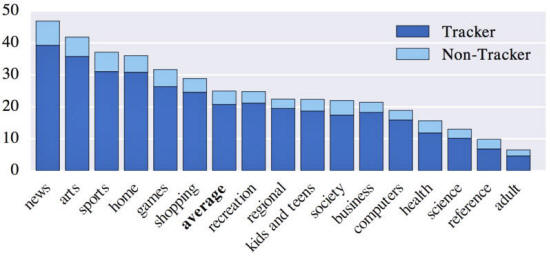

News sites have the most trackers,

according to the researchers.

Online trackers add audio fingerprinting to their arsenal of tools to identify and follow people on the web.

During a scan of one million websites, researchers at Princeton University have found (Online Tracking - A 1-million-site Measurement and Analysis) that a number of them use the AudioContext API to identify an audio signal that reveals a unique browser and device combination.

The method doesn't require access to a device's microphone, but rather relies on the way a signal is processed.

The researchers, Arvind Narayanan and Steven Englehardt, have published a test page to demonstrate what your browser's audio fingerprint looks like.

The technique isn't widely adopted but joins a number of other approaches that may be used in conjunction for tracking users as they browse the web.

For example, one script that they found combined a device's current charge level, a canvas-font fingerprint and a local IP address derived from WebRTC, the framework for real-time communications between two browsers.

The researchers found 715 of the top one million websites are using WebRTC to discover the local IP address of users. Most of these are third-party trackers. Another more widely used method is fingerprinting based on the HTML Canvass API, which aims to deduce the fonts installed on a browser. They found 3,250 first-party sites using this technique.

Meanwhile, Canvass fingerprinting was found on 14,371 sites with scripts loaded from 400 different domains.

The researchers analyzed canvass fingerprinting in 2014, and note three changes since then.

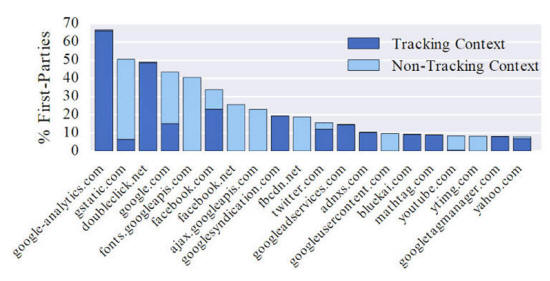

The other key finding, which may be good news depending on your attitude to, ...is that the number of third-party trackers that users will encounter on a daily basis is small.

The researchers say their data suggests there has been a consolidation in the market for third-party tracking, which contrasts to the perception that there has been an explosion in third-party trackers.

And that could be good news in terms of pressuring the industry to make privacy-enhancing improvements.

The research suggests that the number of third-party trackers that users will encounter on a daily basis is small. Image: Princeton University

|