|

from

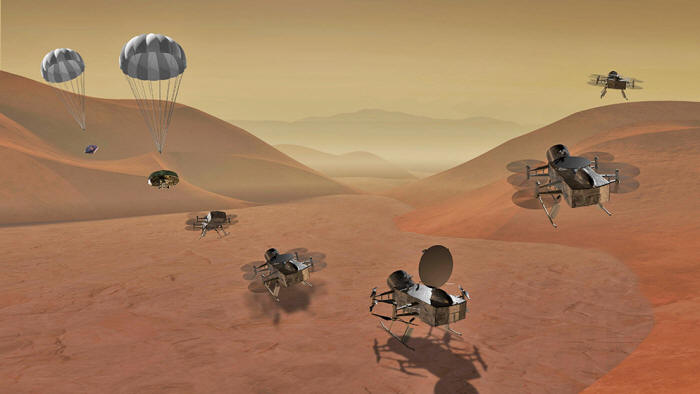

ScientificAmerican Website parachuting onto and then soaring across the surface of Saturn's moon, Titan. Such missions could conceivably find evidence of extraterrestrial in the not-too-distant future.

Credit: NASA major advances in their field, astrobiologists are grappling with how best to discuss possible breakthrough discoveries with the public

Such answers could come by the end of the 2030s from any of a number of initiatives ardently seeking alien life.

By then, samples from Mars will have arrived back on Earth, perhaps containing concrete proof the Red Planet once harbored organisms or still does today.

Spacecraft at Jupiter's Europa and Saturn's Titan will be scouring both moons for signs of life residing in each world's subsurface ocean or, in the case of Titan, on the surface itself.

And advanced telescopes on the ground and in space should be

probing the atmospheres of

potentially habitable exoplanets around

nearby stars, looking for any that share the same biology-infused

cocktail of gases as our own living Earth.

How should they go about informing the world that we are truly not alone in this universe - especially given their field's long, troubled history of dubious claims and false alarms?

They have been fooled before, after all...

Last month in the journal Nature, a group of scientists came to grips with the problem.

Led by NASA's chief scientist James Green, the group proposed a new framework to help verify and then communicate the detection of biosignatures beyond Earth like the Torino scale for assessing the danger of asteroids.

Their idea is to use a scale, from level 1 to level 7, that will allow confidence in any given case to be gradually increased.

Known as the "confidence of life detection," or CoLD scale (Call for a Framework for Reporting Evidence for Life Beyond Earth), its initial steps would merely reflect confirmations that a result is not linked to contamination or some obviously abiotic origin, whereas its final levels would represent robust follow-up observations solidifying a link to life.

There is no shortage of cautionary tales from previous efforts to publicize apparent breakthroughs.

In 1996 President Bill Clinton, heralded the discovery of a meteorite from Mars, ALH84001, that appeared to contain signs of life.

The finding was not confirmed: later analysis poured cold water on the tentative evidence of Martian life. Luckily astrobiology's positive public perception emerged relatively unscathed.

Yet a repeat of that incident could now have disastrous consequences.

More recently, the supposed detection on Venus of atmospheric phosphine, a possible biosignature gas, had many suggesting a biological origin, but that detection has itself since been called into question.

More outlandish ideas, such as the suggestion that the interstellar object 'Oumuamua found in our solar system in 2017 may have been an alien spacecraft rather than an asteroid or comet, have been met with widespread disdain from scientists and have the potential to dampen confidence in genuine detections of life.

The CoLD scale could prevent scientists from "crying wolf" in this manner, Green says, because any overly cavalier claims would not pass the more stringent tests required to progress up the scale.

Deciding how to approach actual detections of biosignatures is a topic other scientists have been considering, too.

In July scientists met virtually at the Standards of Evidence for Life Detection workshop, led by NASA's Network for Life Detection (NfoLD) and Nexus for Exoplanet System Science (NExSS), to discuss the idea of establishing a framework much like CoLD.

Hundreds of scientists took part, with many in favor of more rigorous communications protocols.

If scientists were to adopt the CoLD scale, the first of its be seven steps, or levels, would be the actual detection of a potential biosignature.

Next, scientists would need to rule out contamination before demonstrating how the signal could be biological in origin. Nonbiological sources would then need to be ruled out, followed by an independent additional detection of a similar biosignature.

Further observations would need to rule out nonbiological ideas before, finally, follow-up observations showed other examples of biological activity in the same environment, making a detection a level 7 - essentially, proof of alien life.

Part of the hope is that the scientific community at large would agree to use such a scale.

Agencies such as NASA might also agree to do so, which would also help dictate future missions.

Ultimately, once use of a scale like CoLD became ubiquitous, reviewers of journal papers could require authors to include it in any claim of biosignature detection.

The call for such a step-based approach is driven by the unescapable likelihood that any initial detection of alien life is likely to be ambiguous rather than a smoking gun: any glaringly obvious indication of alien life would have been clear by now, decades into the hunt.

So more subtle searches based on circumstantial evidence are coming to the fore.

In October, for example, ZoŽ Havlena, a Ph.D. student at the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, was part of a NASA-funded team that traveled to cave walls in Italy's Apennine Mountains to collect and study samples of a mineral called gypsum, which is sometimes associated with biological activity and may be present on Mars.

Elsewhere on Mars, NASA's Perseverance rover is collecting rocky samples to return to Earth in the early 2030s that may contain evidence of life.

Its first cache, however, was actually a sniff of the Martian atmosphere, Green says, to tease out whether or not the thin air around the rover contained methane.

Previous missions - as well as telescopes on Earth - have found evidence for occasional bursts of the gas suffusing Mars's atmosphere.

Currently on the CoLD scale, methane on Mars would rank at "about a [level] 4," Green says.

But if Perseverance's sample is found to contain not only methane but methane rich in an isotope called carbon 12, that could change.

The next step would be to fly across the surface - with a drone like Perseverance's Ingenuity but bigger - to localize the methane to a source that could be directly investigated.

Outside of Mars, both Europa and Titan are promising locations to look for life because of their extensive subsurface oceans and, in the case of the latter, a thick atmosphere and lakes of liquid hydrocarbons.

But any evidence found at the two moons is also likely to require careful analysis.

Madeline Garner, a graduate student at Montana State University, is currently investigating whether an instrument could be designed for robotic spaceflight that could identify the existence of DNA and RNA on these and other alien worlds.

Her research into solid-state nanopore technology, currently used on the International Space Station to sequence DNA, could provide a conclusive detection capability for space probes.

Beyond our solar system, scientists are preparing for a new era of exoplanet studies that could reveal tentative evidence for life on other worlds.

At ESA, work is afoot on the Planetary Transits and Oscillations of Stars (PLATO) mission - set to launch in 2026 - which will seek to find elusive Earth-like worlds orbiting sunlike stars.

PLATO will aim to address that.

If or when such worlds are found, sophisticated orbital observatories currently being discussed - beyond the realm of NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled to launch this December - could lavish them with deeper scrutiny.

Such telescopes could include a multi-billion-dollar project now being considered by NASA, perhaps launching in the 2040s, that could directly image Earth-like planets around sunlike stars, crudely sniffing their atmospheres for signs of habitability and life and even mapping their surfaces.

If some verdant aqueous world also displayed biosignature gases such as oxygen and methane, many researchers would be convinced their long search for life had been successful.

A framework like CoLD could go a long way to helping anyone, from scientists to journalists to the general public, assess how excited to be about such detections.

But not everyone is convinced by the idea.

Caleb Scharf, director of astrobiology at Columbia University, doubts that researchers could control the narrative and is uncertain whether the public would comprehend the carefully constructed messaging.

What is certain, though, is that things are progressing apace.

Research across a range of fields, from examining caves on Earth to visiting distant worlds, is on the cusp of bringing us closer to the discovery (or continued refutation) of alien life than ever before.

Deciding how to communicate such a thing to the world, whether through a framework like the CoLD scale or otherwise, is something that may well be worth discussing sooner rather than later.

|