|

04 August 2008

from

TheTelegraph Website

Spanish version

A lost world has been found in Antarctica, preserved just the way it

was when it was frozen in time some 14 million years ago.

The fossils of plants and animals high in the mountains is an

extremely rare find in the continent, one that also gives a glimpse

of a what could be there in a century or two as the planet warms.

|

|

|

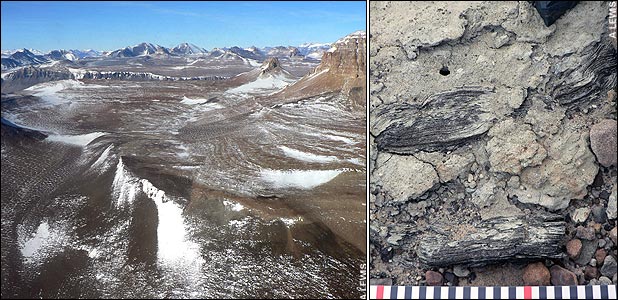

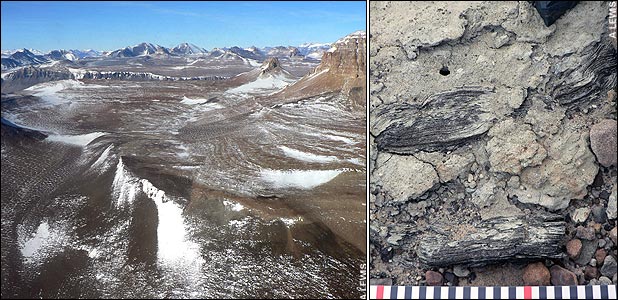

Mt Boreas in

the western Olympus Range, Dry Valleys (left) and moss

mat (right), the Dry Valleys climate prevented

decomposition |

A team working in an ice-free region has

discovered the trove of ancient life in what must have been the last

traces of tundra on the interior of the southernmost continent

before temperatures began to drop relentlessly.

An abrupt and dramatic climate cooling of 8°C in 200,000

years forced the extinction of tundra plants and insects and brought

interior Antarctica into a perpetual deep-freeze from which it has

never emerged, though may do again as a result of climate change.

An international team led by Prof David Marchant, at Boston

University and Profs Allan Ashworth and Adam Lewis, at

North Dakota State University,

combined

evidence from glaciers, from the preserved ecology, volcanic ashes

and modeling to reveal the full extent of the big freeze in a part

of Antarctica called the Dry Valleys. combined

evidence from glaciers, from the preserved ecology, volcanic ashes

and modeling to reveal the full extent of the big freeze in a part

of Antarctica called the Dry Valleys.

The new insight in the understanding of Antarctica's climatic

history, which saw it change from a climate like that of South

Georgia to one similar to that seen today in Mars, is published in

the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"We've documented the timing and the

magnitude of a tremendous change in Antarctic climate," said

Prof Marchant.

"The fossil found allow us to examine Antarctica as it existed

just prior to climate cooling at 13.9 million years ago. It is a

unique window into the past. To study these deposits is akin to

strolling across the Dry Valleys 14.1 million years ago."

The discovery of lake deposits with

perfectly preserved fossils of mosses, diatoms and minute

crustacea called ostracods is particularly exciting,

noted Prof Lewis.

"They are the first to be found even

though scientific expeditions have been visiting the Dry Valleys

since their discovery during the first Scott expedition in

1902-1903," he said.

"If we can understand how we got into this relatively cold

climate phase, then that can help predict how global warming

might push us back out of this phase.

For the vast majority of Earth

history there was no permanent ice like is common today at the

poles and even the tropics at high elevation. There's been a

progressive cooling going on for 50 million years to get us into

this permanent-ice mode; the formation of a permanent ice sheet

on Antarctica plays a big role in that cooling.

"Studies like ours that establish when and how climate

thresholds were crossed along the way can be used to predict

climate thresholds going the opposite direction, from cool to

warm.

"Although, to be fair, we're looking at one that is very far

away; warming would have to be greater than what is predicted

for the next one or two centuries to cause a melting of the East

Antarctic Ice Sheet. The west Antarctic Ice Sheet is much more

vulnerable.

Prof Ashworth is struck by how

species of

diatoms and

mosses are indistinguishable

from living ones.

Today they occur throughout the world -

except Antarctica.

"To be able to identify living

species amongst the fossils is phenomenal. To think that modern

counterparts have survived 14 million years on Earth without any

significant changes in the details of their appearances is

striking.

It must mean that these organisms

are so well-adapted to their habitats that in spite of repeated

climate changes and isolation of populations for millions of

years they have not become extinct but have survived."

What caused the big freeze is unknown

though theories abound and include phenomena as different as the

levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and tectonic shifts that

affected ocean circulation.

|

combined

evidence from glaciers, from the preserved ecology, volcanic ashes

and modeling to reveal the full extent of the big freeze in a part

of Antarctica called the Dry Valleys.

combined

evidence from glaciers, from the preserved ecology, volcanic ashes

and modeling to reveal the full extent of the big freeze in a part

of Antarctica called the Dry Valleys.