|

Staff Writer December 12, 2011 from OurAmazingPlanet Website

snapped during a NASA

research flight in October 2011. One hundred years ago this week, on a fine summer afternoon, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen and four travel-weary companions plunged a bright flag atop a spindly pole into the Antarctic ice, marking their claim as the first humans to set foot at the bottom of the world.

The South Pole was theirs.

On Dec. 14, 1911, two months after they

set out from the continent's coast, the men had reached their goal -

a frozen plain of endless white in the middle of the highest,

windiest, coldest, driest and loneliest continent on Earth. Amundsen and crew take an observation at the pole in an image from the Norwegian explorer's "The South Pole," an account of his historic trek.

CREDIT:

NOAA/Department of Commerce, Steve Nicklas, NOS, NGS. Watchful satellites sail overhead; probing radar and lasers have allowed scientists to peer beneath the thick ice.

And yet, in spite of the reach of these

new tools, the continent still holds its secrets close. Many

mysteries remain, and they are far more intricate and nuanced than

the uncharted wilderness Amundsen and Scott confronted.

Now, instead of mapping new geographical

discoveries, scientists are seeking to map the inner workings of the

strange forces at play in Antarctica, from the biological mechanisms

that allow tiny organisms to seemingly awake from the dead, to the

little-understood forces that are gnawing away at the continent's

ice - with increasing vigor.

Two massive ice sheets, nearly 3 miles

(4 kilometers) thick in some places, cover about 99 percent of

the

continental landmass. Including its islands and attached floating

plains of ice, Antarctica is roughly 5.4 million square miles (14

million square km), about one-and-a-half times the size of the

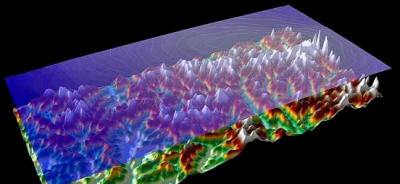

United States. Airborne imaging technology allowed scientists to see the rugged topography of the Gamburtsev Mountains, hidden entirely beneath the ice sheet.

CREDIT: Michael

Studinger.

And it was beneath the ice that

scientists made one of Antarctica's most screenplay-worthy

discoveries: a sweeping kingdom of rocky slopes and liquid lakes,

secreted under the ice for millennia:

During a 1958 mapping expedition, a Soviet team was trekking from

the coast across the interior of the eastern half of the continent,

and detonating explosives every hundred miles to measure the

thickness of the ice.

Big mountains. The team had stumbled upon what were later dubbed the Gamburtsev Mountains, a range of steep peaks that rise to 9,000 feet (3,000 meters) and stretch 750 miles (1,200 km) across the interior of the continent.

Yet, she added, the truly mysterious part of the hidden mountains is not that they exist, but how they still exist.

The inexorable march of geological time

erodes mountains away (if we came back in 100 million years, the

Alps would be gone, Bell said) and the Gamburtsevs, at the ripe old

age of 900 million to a billion years old, should have been worn

down eons ago.

It happened during a rifting event, Bell said, when tectonic forces were wresting apart continental masses during the breakup of Gondwana, the ancient supercontinent.

At the time, the eroded mountains' heavy roots apparently underwent a density change - as though a bar of solid chocolate suddenly morphed into the fluffy stuff inside a Three Musketeers bar - which buoyed the mountain range back up,

Exactly how that change in the Gamburtsevs' root happened is a mystery.

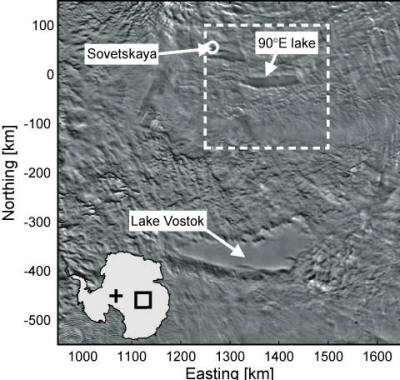

Land o' lakes

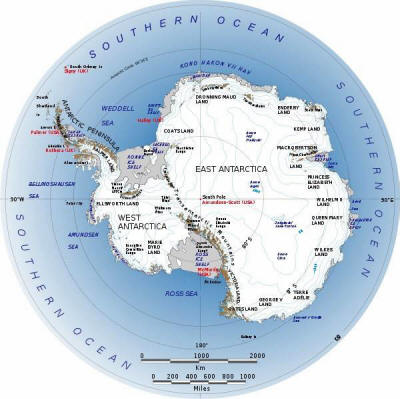

A map of Antarctica. CREDIT: NASA.

About the size of Lake Ontario, it is

the largest of the more than 200 liquid lakes strewn around the

continent under the ice.

The Russians, at Lake Vostok, and

the

British, at Lake Ellsworth, may have samples by 2012.

What is proven, Priscu said, is that bacteria are in the ice.

Not many, by microbial standards - 300 cells in 1 milliliter of ice vs. 100,000 cells in seawater - but they're there, in tiny veins of liquid water that crisscross the solid ice and serve as "little houses," Priscu said, which also contain nutrients that could feed a hungry microbe.

In the lab, ancient bacteria from ice samples 420,000 years old, retrieved from more than 2 miles (3 km) inside the ice sheet, have quickly shown signs of life.

However, it's not clear if the ice is simply acting as a preservative, and keeping the same microbes intact until they're given a warm meal, or if an active microbial community is plodding along inside the ice sheet.

CREDIT: British Antarctic Survey.

Barnes, speaking from a research vessel just off the Antarctic Peninsula, said one of the biggest mysteries is,

Leggy sea spiders the size of dinner plates rule Antarctic waters, yet other creatures common to the rest of the Earth's oceans, such as slugs, are strangely absent.

Some creatures grow to enormous size, while others are unusually small.

Griffiths said that one area of great interest is the virtually unexplored ocean beneath the ice shelves that ring the continent. The outlets of glaciers, ice shelves are many hundreds of feet thick, and they are colossal.

The largest, the Ross Ice Shelf, is 197,000 square miles (510,680 square km), or 3.7 percent of the total area of Antarctica.

A British-made oceangoing robot, dubbed AutoSub, made some of the first-ever observations beneath an ice shelf in 2009, during several dives in western Antarctica.

Although the robot didn't offer a glimpse of anything living there - it's not equipped with cameras or a sampling arm - it did provide invaluable data for scientists studying the swift-moving Pine Island Glacier ice shelf, which might be thought of as ground zero for the biggest Antarctic mystery of all, in the minds of many scientists:

Icy disappearing act

The ice that is of most concern is the

West Antarctic Ice Sheet, which is undergoing unprecedented changes,

and is likely the biggest potential player in future global sea

level rise.

Also, large portions of the bottom of

the ice shelf are below sea level - these two factors make the ice

shelf particularly vulnerable, according to Robert Bindschadler,

a glaciologist and NASA scientist emeritus.

where Bindschadler will be doing field work. A giant rift, part of a natural calving process, has recently formed on the ice shelf.

CREDIT: Michael

Studinger, NASA. All of this has come as something of a surprise to the scientific community.

As recently as the 1980s, ice sheets weren't even taken into account when researchers modeled how climate change might affect sea level, Bindschadler said.

The data tell a far different story:

Now that scientists know swift changes are occurring, they're trying to figure out how it's happening - and all the evidence has revealed that the ocean is the culprit.

That's because it appears that most of the action is happening beneath the ice shelves - those giant plains of floating ice that cling to the continent's edges.

Satellites and other observational tools can't get a detailed look at what's happening under them.

Researchers do know that ice shelves act

as giant door stops for glaciers. When ice shelves get thinner or

collapse all together, glaciers speed up and dump more water into

the ocean, raising sea levels.

The overarching goal for Bindschadler

and many other Antarctic researchers is to hand off enough data to

modelers so they can figure out how the Antarctic ice is going to

change in the coming decades, and how those changes will affect the

rest of the world.

Although that is unlikely to happen for many thousands of years, the ice sheet has increasingly lost mass over the last two decades, and the glaciers that serve as its outlet to the sea are accelerating.

Even comparatively small changes in the

world's three ice sheets (the Greenland, the East Antarctic and the

West Antarctic) would have dramatic effects. A 1 percent volume

change in all of them would raise sea levels by about 26 inches (65

centimeters), Bindschadler said.

|