|

by Douglas Fox

12

December 2018

Near the Whillans drill site toward the Trans Antarctic mountains along the edge of the ice shelf. A perpetually dark landscape of lakes and rivers exists underneath Antarctica's thick glacial blanket. Credit: J. T. Thomas

researchers in Antarctica will drill through 1,100 meters of ice into a lake that has remained sealed for millennia.

Here's what they

hope to find.

Within the next two weeks, a team of technicians will use that hot water to melt a hole through 1,100 meters of ice, straight down to the bottom of the Antarctic ice sheet.

Their quarry is a hidden

lake that has been cut off from the rest of the world for thousands

of years. The life they expect to find there inhabits one of the

most isolated ecosystems on Earth.

Despite temperatures that

are likely to stay below 0°C, the lake doesn't freeze, because of

the intense pressure from the ice above. Researchers discovered its

ghostly silhouette a little more than a decade ago through satellite

observations, but no human has directly observed the lake.

Then, a team of

researchers from more than a dozen universities will hoist samples

of water and mud from its interior. The scientists will also send a

skinny, remote-operated vehicle down through the 60-centimeter-wide

hole to explore the dark waters with video cameras and grab samples

with a claw.

This time, they wonder whether the cameras of the submersible might even spy animals in the black waters.

The team retrieves the

first terrestrial samples from

Subglacial Lake Whillans.

from the bottom of Lake Whillans during a drilling project in 2013.

Credit:

J.T. Thomas

Its aim is to explore the ice-shrouded environment of perpetually sunless rivers, lakes and wetlands that exists in Earth's polar regions and covers an area as big as the United States and Australia combined.

This ecosystem is much

more isolated than even the deepest ocean trenches.

Cores drilled from the bottom of the Ross Sea nearby suggest that this ice sheet has collapsed dozens of times over the past 6 million years.

Lake Mercer is about 800 kilometers inland of those sites in the Ross Sea and could yield important clues about the ice sheet's periodic advances and retreats during previous cold and warm spells, says David Harwood, a bio-stratigrapher at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln who will be present for the drilling.

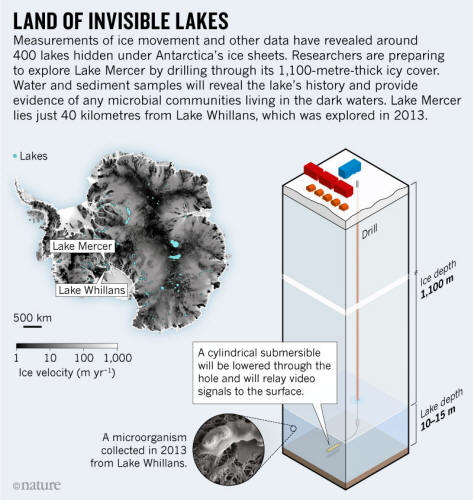

Helen Fricker, a

glaciologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La

Jolla, California, realized that they were

subglacial lakes filling and

emptying, causing the ice overhead to lift and then drop (see below

'Land of invisible lakes').

Tristy Vick-Majors/SALSA M. R. Siegfried & H. A. Fricker Ann.

Glaciol.

59, 42–55 (2017).

The water from Lake Whillans teemed with 130,000 microbial cells per milliliter - a population 10-100 times bigger than some researchers expected. 2

Many of the microorganisms obtained their energy by oxidizing ammonium or methane, probably from deposits at the bottom of the lake. 3,4

That was a key insight,

because it suggested that this ecosystem - seemingly cut off from

the Sun and photosynthesis as an energy source - was still dependent

on the outside world in an indirect way.

Evidence of this food source came from Reed Scherer, a micro-palaeontologist at Northern Illinois University in DeKalb, who was part of the Whillans project.

He found the shells of diatoms (single-celled algae) and the skeletal fragments of sea sponges littered throughout the lake's mud.

When they drilled into Lake Whillans, researchers thought it had been covered by ice for at least 120,000 years, or possibly up to 400,000 years, coinciding with the last time the West Antarctic Ice Sheet was thought to have melted so dramatically that the lake area had been exposed to the ocean.

But in June, Scherer

reported evidence that Lake Whillans was connected to the ocean

possibly as few as 5,000-10,000 years ago5.

When the researchers drill into Lake Mercer, they'll come armed with new instruments to answer some of the questions that emerged from the previous project.

Mercer is twice the size of Lake Whillans, and five times deeper - but was probably connected to the ocean at the same time as Whillans, says Scherer.

Given the realization that the lakes might not have been cut off for tens of thousands of years, the team hopes to learn what Lake Mercer's inhabitants are eating.

They could subsist on ammonium, methane and other organic compounds from relatively fresh food deposited a few thousand years ago, or they might consume less-easily digested material that is millions of years old.

Discovering the

microorganisms' diet could help the team to predict how much life

might inhabit other sub-glacial lakes that have been isolated for a

lot longer.

John Priscu

suspects that if

life exists on Mars, much of it

would be living off carbon that was laid down by photosynthetic

organisms, when the planet was wetter.

Brad Rosenheim, a palaeo-climatologist at the University of South Florida in Tampa, will use an advanced technique to analyze the mud for carbon-14, a radioactive isotope formed in the atmosphere that decays to undetectable levels within about 40,000 years.

This could reveal how

much of the lake-bottom muck was laid down the last time the ocean

reached this spot.

This could provide

further information on what today's resident microorganisms are

eating.

That could help researchers who are trying to forecast when global warming will trigger runaway melting of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, which in turn could raise sea levels around the globe by several meters.

In fact, some researchers wonder whether they missed something major when they drilled into Lake Whillans in 2013. At that time, Whillans's oxygen levels were low - but survivable by a broad range of aquatic animals. And the abundant bacteria in the lake could potentially support microscopic animals such as worms, rotifers or tardigrades.

But the researchers were

surprised when DNA studies showed no evidence of such creatures.

2 And a video camera that was lowered into the hole for a

few minutes did not record any such life.

Beneath 755 meters of ice, they encountered a sliver of sea water just 10 meters thick.

Because the water at that point is more than 600 kilometers from the sunlit edge of the floating ice shelf, researchers did not expect to find complex life. And when they lowered a camera into the hole, the blank images that streamed back confirmed their suspicions - for eight days.

Then, they sent down a

remote-operated vehicle, and its video cameras soon caught fish,

amphipod crustaceans and other animals milling about - in an

environment that should not have been able to feed such creatures,

because microbial life was scarce.

Priscu looks forward to

that moment. He thinks that the lake should be capable of sustaining

animals.

References

|