| Sending the slow,

cumbersome seaplanes to the Antarctic to fly in a frigid, hostile

environment seemed totally irrational at first thought, however sense

could be made from such a decision when one considered their long-range

flight capabilities as well as their ability to operate in open sea

conditions around the entire continent rather than restricted to land-based

operations.

The PBM Martin Mariner seaplane was satisfactorily equipped

to meet the many technical requirements of such an operation.

The

planes had served admirably in many open sea recoveries of downed

pilots. The VH-4 Squadron was often involved in semi-open sea maneuvers

during OPERATION CROSSROADS. However, neither the aircraft

nor the crewmen were experienced and properly equipped for the extreme

weather conditions which awaited them. For example, the planes were

lacking adequate deicing and navigation equipment.

But the pilots

and crews of VH-4 were otherwise well experienced and available. The

plane commanders were certainly qualified and would adapt quickly

to flying conditions in the Antarctic.

They would be

subjected to numerous intangibles upon reaching the Antarctic. Since

most of the interior of the continent was uncharted, elevations

of the terrain was, for the most part, an unknown. Couple that with

poor weather forecasting and you have a recipe for exceptional danger.

A PBM crew flying off the USS PINE ISLAND

(Eastern Group) would experience the unforgiving flying conditions

firsthand as they

crashed on Thurston Island,

resulting in the first loss of American life in the Antarctic.

Antarctica

is known to have the highest winds on the face of the earth and

weather conditions can change dramatically in only minutes.

Since the squadron

was due to be decommissioned, pilots and enlisted crew vacancies

were not refilled as the squadron slowly disbanded. As a result,

when the squadron touched down in Hawaii, there were only 10 pilots

and approximately 50 crewmembers available for the "volunteer"

expedition.

When questioning the alternative to accepting the "voluntary"

assignment the answer was,

"probably reassignment as a replacement

pilot or crew to a squadron in the Far East."

Nine pilots and

15 crewmembers eventually volunteered.

They may not have been completely

willing, but they nevertheless were true volunteers in every sense

of the word. Classification of OPERATION HIGHJUMP

was so sensitive that the pilots and crew were instructed to keep

the details of their assignment under wraps, even from their wives

and family members. Most, if not all of the men, chose to ignore

this order.

After the decommissioning

of VH-4 in San Diego, California, the OPERATION HIGHJUMP

volunteers reported to COMFAIRWING 5 at Naval Air Station Norfolk,

Virginia on November 1, 1946 to begin preparations for the expedition.

Demands and priority for sophisticated equipment for OPERATION

HIGHJUMP apparently was never passed down to the logistics

people at the naval air station.

The highly classified nature of

the expedition only compounded the problems. Somehow news of the

"classified" expedition was leaked to the newspapers since

the local papers announced that the Western Group was on its way

to the Antarctic. Although a breach of secrecy, once this news hit

the papers equipping of the expedition picked up steam.

Meanwhile,

"Training

was constant and intensive from November 5 through November 23 with

flight crews attending numerous classes on aerial mapping, tri-metrogon

photography, cold weather operations in seaplanes, flight planning,

polar grid navigation and the use of the astro compass. Technical

training for the radiomen and radar operations was also accomplished."

(Captain Robert H. Gillock, USN retired, Captain Paul J. Derocher,

USN retired, Mariner/Marlin Newsletter, February 2001, pg. 26).

All of the men were trained in the use of survival gear as sleds,

axes, stoves and tents were to be carried aboard the aircraft while

flying their missions.

The three PBM-5

"Mariners" were delivered to the group in mid-November

and flight-tested. Meanwhile, upon completion of their training

the men were issued standard navy heavy-weather winter flight gear

together with charts of the Antarctic.

They were assigned to the

USS CURRITUCK, which together with the

USS

HENDERSON (Destroyer) and

USS

CACAPON (Fleet Oiler), would become Task Group 68.2,

a.k.a. the Western Group. On November 26, all three PBM's of the

Western Group departed NAS Norfolk for San Diego via NAS Pensacola

and NAS Corpus Christi.

Four days later the planes arrived in San

Diego and on December 1, the final PBM was hoisted aboard the USS

CURRITUCK. Their participation in the expedition would begin

the next day when the ship got underway for the southern polar region.

Their mission was to explore and photograph the eastern longitude

of Antarctica.

|

|

The first

flight of the Western Group was made on December 24, 1946.

On January 1, 1947, a 9.2-hour flight was made to the vicinity

of the magnetic South Pole. However, the special 3-phase gyro

used for navigation was incorrectly wired.

Fortunately, the

USS CURRITUCK picked up the aircraft's emergency IFF signal which was responsible for guiding the aircraft

back to the ship.

Upon returning to the ship it was discovered

that the aircraft was some 100 miles in error. Early on in

the expedition, the planes of the Western Group were dispatched

to help save the submarine

USS

SENNET.

A participant with the Central Group,

she was the first submarine to venture into Antarctic waters.

Squeezed by the ice and threatened to be crushed, the PBM's

would search for leads to open water.

The PBM's were unsuccessful

in their search, however the USS SENNET was

eventually freed from the grips of the ice, escaping to open

waters in the Ross Sea where she would serve as a weather

reporting station.

|

The pilots quickly

adapted themselves to flying in the Antarctic.

Careful attention

was paid to making landings so that no undue stress would be placed

on the aircraft. Takeoffs and landings were often made parallel

to the ocean swells and all takeoffs were JATO (Jet-assisted takeoff)

assisted. Takeoff weight could not exceed 22 tons as that was the

maximum weight the hoisting hook on the USS CURRITUCK

could support. Upon landing, the crews worked like a well-oiled

machine in their ability to retrieve and hoist the plane onto the

ship within a matter of minutes.

The Western

Group was pressured to get to their Antarctic base of operations

in the shortest possible time. Most of what is told here was originally

considered hearsay, but was later established as fact.

The Western

Group's primary objective was to explore and photograph, by air,

as much of the Antarctic continent within its operational area as

possible. This region, never before seen by human eyes, would be

claimed by them for the United States of America.

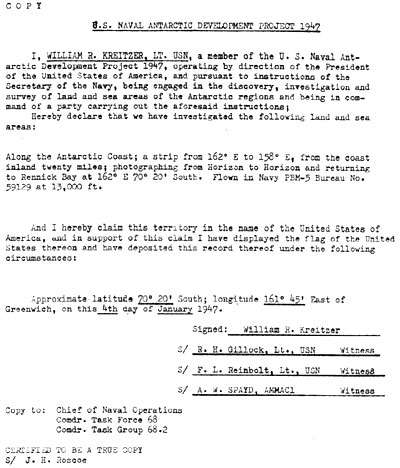

"Flying within

predetermined grids, contiguous territorial areas were identified

by their coordinates and recorded and claimed for the United States

by the patrol plane commander. Each claim was witnessed by three

other crew members.

After a copy was made for transmittal to the

State Department, the original copy of the claim was placed in a

waterproof container to which approximately 10 feet of line and

a small United States flag were attached. The canister and flag

were then thrown overboard to land on the claimed territory, the

crew being careful to avoid having the line and canister entangle

in the aircraft's tail."

(Captain Robert Gillock, USN Ret.,

Captain Paul Derocher, USN Ret., Mariner/Marlin Newsletter, February

2001 pg. 27).

The pilots and

crews of the Western Group accomplished a great deal during OPERATION

HIGHJUMP.

Unlike the crash and tragic loss of life on PBM-5

George One (assigned to the USS PINE ISLAND in

the Eastern Group), this group experienced no accidents.

Accomplishments

included:

-

Nineteen

claims of previously unexplored territory made in the name of

the United States. All claims have been recorded by the US State

Department and are now on file in the National Archives.

-

A

total of 405,378 square miles of Antarctic were photographed.

-

A total

of 36 flights were launched from the open seas off the Antarctic

ice pack.

GEOGRAPHIC

NAMES IN ANTARCTICA

NAMED AFTER HIGHJUMP PILOTS & NAVIGATORS

1946-47

|

PILOT

/ NAVIGATOR

|

GEOGRAPHICAL

NAME

|

SOUTH

LATITUDE

|

EAST

LONGITUDE

|

|

Bunger

|

Bunger

Hills

Bunger Lakes

Bunger Oasis |

66°

17'

66° 17'

66° 17'

|

100°

47'

100° 47'

100° 47'

|

|

Gillock

|

Gillock

Glacier

Gillock Island |

72°

00'

70°

26'

|

24°

08'

71°

52'

|

|

Gist

|

Gist,

Mount |

67°

21'

|

98°

54'

|

|

Jennings

|

Jennings

Glacier

Jennings Lake

Jennings Promontory |

71°

57'

70 ° 10'

70 ° 10'

|

24°

22'

72°

32'

72°

32'

|

|

Kreitzer

|

Kreitzer

Glacier

Kreitzer Bay

Kreitzerisen |

70°

22'

66° 30'

72 ° 13'

|

72°

36'

109°

30'

22°

10'

|

|

Reinbolt

|

Reinbolt

Hills |

70°

29'

|

22°

30'

|

|

Rogers

|

Rogers

Glacier

Rogers Peaks |

69°

59'

72 ° 15'

|

73°

04'

24°

31'

|

|

Stevenson

|

Stevenson

Glacier |

70°

66'

|

72°

48'

|

|

Reynolds

|

Reynolds

Trough |

66°

17'

|

100°

47'

|

GEOGRAPHIC

NAMES IN ANTARCTICA

NAMED AFTER HIGHJUMP CREWS

1946-47

|

CREW

#1

Pilot William J. Rogers, Jr.

|

GEOGRAPHICAL

NAME

|

SOUTH

LATITUDE

|

EAST

LONGITUDE

|

McKaskle

Statler

Mistichelli

Maris

Hargreaves

Peterson

|

McKaskle

Hills

Statler Hills

Mistichelli Hills

Maris Ntk.

Peterson Glacier

|

70°

00'

69° 50'

70° 02'

111° 00'

69° 59'

|

73°

00'

73° 10'

72° 50'

65° 20'

73° 10'

|

|

CREW

#2

Pilot David E. Bunger

|

|

|

|

|

Fuller

Draves

Countess

Smith

Booth

Garan

|

Smith Ridge

|

70°

02'

|

72°

50'

|

|

CREW

#3

Pilot William R. Kreitzer

|

|

|

|

|

Preston

Spayd

Branstetter

Thil

Whisnant

Ellis

|

Preston

Pt.

Spayd Island

Branstetter Rocks

Thil Island

Whisnant Ntk. |

70°

17'

70° 33'

70° 07'

70° 08'

70° 00'

|

71°

45'

72° 12'

72 ° 40'

72°

35'

73°

05'

|

|