|

by Gentry Underwood

January 05,

2018

from

Medium Website

Spanish

version

Primitive homo martis

surveying the environment

(Artist's conception, early 21st century)

Recently a friend chided me for being an Elon Musk fanboy:

"I'm so tired of all

these Muskophiles," she said when I brushed off the dig. "What

is it you're all so excited about anyway?"

"Tesla for

starters," I responded. "There's a company whose

explicit reason for existence is to disrupt our fossil fuel

addiction. While most everyone else is whining about global

warming, Elon has found a way

within capitalism to

combat it."

"But what

really gets me amped," I added, "is Mars."

"Pffft,"

she sounded with a roll of the eyes.

"Mars? I am so

tired of hearing about Mars! What

an escapist's dream - blasting off to some

other planet when it's this one that's in trouble!"

The 6th Mass-Extinction

She had a point.

The Earth is dying. It's shedding life at a remarkable rate...

Ocean

acidification is occurring at

breakneck speed with

devastating consequences to marine life, in seas already on the

brink of being

fished to death.

Studies in Germany have shown that the insect

population (Earth's thankless workforce of plant pollination) has

plummeted a staggering 75% since measurement started 30 years

ago.

And of course we all know the rest

- the earth is rapidly

heating up, the ice caps are melting - our global ecosystem is

deeply out of whack.

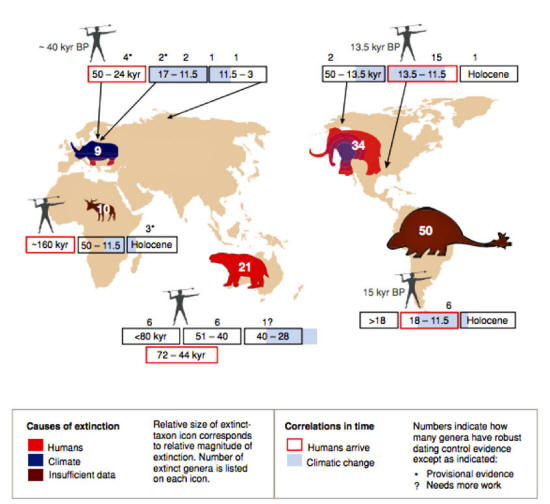

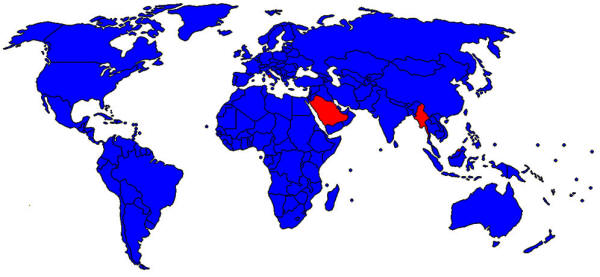

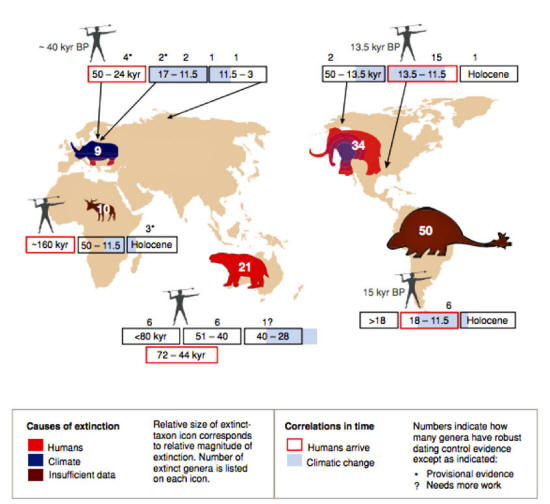

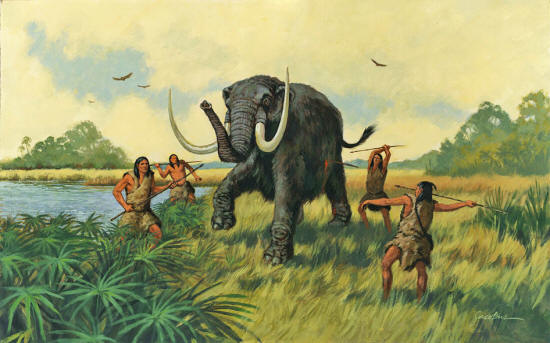

Worse still, this

isn't just some freak moment in history, but

the latest in a long saga of humans decimating nature. You can

literally chart a course of extinction around the globe by

tracking the migration of early humans.

Wherever we show up, megafauna (like wooly mammoths and sabretooth tigers) disappear...

Chronology of megafauna extinction.

Koch & Barnosky (2006)

Where humans go,

the death of life follows...

We're not just a keystone species,

we are hands-down the single most destructive force to impact this

planet since a large asteroid took out the dinosaurs (and

75% of life on Earth) 65 million years ago.

Put succinctly,

humans are the 6th mass extinction.

Agent Smith

was onto

something

Yeesh...

-

The idea

that our planet is dying? Terrifying.

-

The idea that

we're the reason why?

Horrific.

-

What the hell does one do with that?

Surprise, we're the bad guys?

That's not the kind of story most people are eager to believe.

Well, depression,

for starters.

If you haven't already felt that sickening "oh

god" feeling in the pit of your stomach, chances are you'll

find little of value in the rest of this post. Nothing I'm about to

say will sound the least bit reassuring unless you're already

painfully aware of the depth of shit we're in.

If there is hope

here, it's in the idea that we might find some way to change this

pattern.

To stop destroying the planet that gives us life and start

stewarding it instead.

-

But how would such a change occur?

-

How would

8 billion humans transform from self-interested actors who are

unintentionally devouring the planet into considerate, capable

caretakers of a global ecosystem?

That's not the kind of change

that's going to just happen on its own.

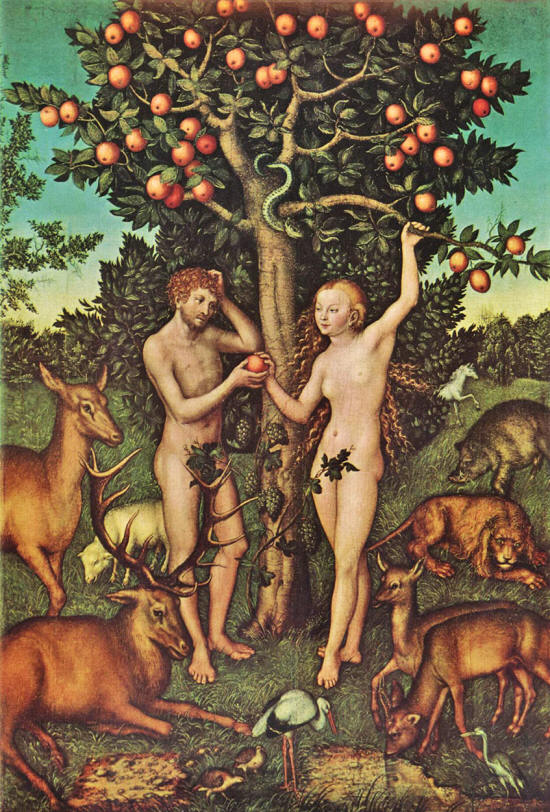

Original Sin

If there's a way

forward, it must begin with understanding the present.

-

What is it

about humans that results in our current situation?

-

We don't

want to destroy the

planet, so why does it happen?

Many have argued

that the fundamental problem is

technology, man's attempts to better himself through the

creation of ever-more-powerful tools that (unfortunately) have

ever-more-complicated side effects.

Some point to

industrialization as the moment our relationship with the

Earth began to turn.

Others say

agriculture is to blame: that when we went from being

hunter-gatherers to food cultivators, the resultant cultural

revolution took us out of a 'garden of Eden' and into (broken)

civilization.

In each case the basic idea is the same:

humans "inadvertently"

harm both their world and themselves when they attempt to

reshape nature for their own purposes.

Live with nature or

separate

that-which-serves

from the rest?

This narrative is

- quite literally - as old as they come...

In ancient Hebrew, the

forbidden tree that ends Man's tenure in Paradise is called

עֵץ הַדַּעַת טוֹב

וָרָע, or the tree of

knowledge of good and evil.

Humans, the Bible opens by telling

us, once faced a fundamental choice:

dare to divide the world into

good (literally "that which

is valuable to us") and evil

(that which is not), or accept life as it was.

And humans, the

story goes, chose poorly.

But this most

ancient of moral dilemmas presents us with an impossible situation,

for there is no world where humans exist in harmless camaraderie

with nature.

If this is indeed the fundamental problem, then there

is nothing for us to do but give up, for there is no version of

reality where man can not

eat from such tree and still survive.

Our very existence derives

explicitly from our unique ability to coordinate our creative

capacities to reshape nature - it's only by separating

good from

evil that humans are here

at all.

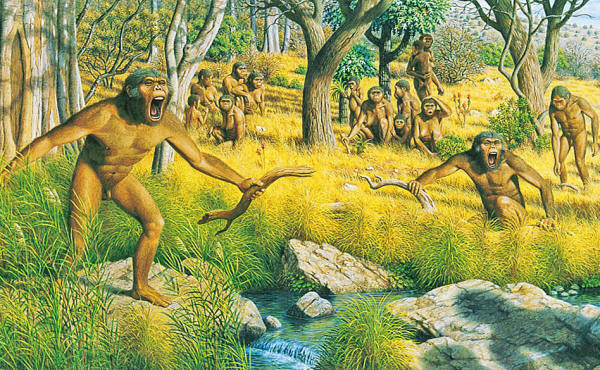

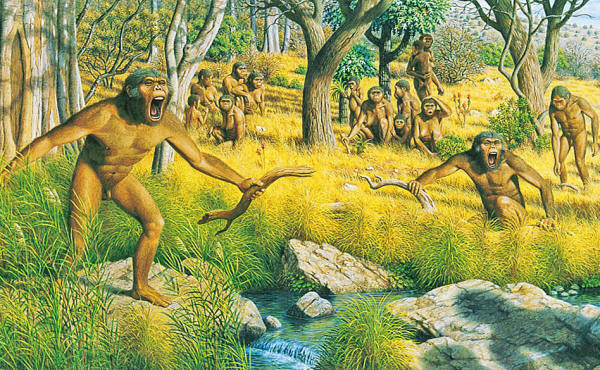

How does a band of

apes fight a lion?

Homo sapiens,

literally "wise men", share roughly

98% of DNA with chimpanzees (for comparison sake, we share 99% with

one another and 50% with a banana).

Once, a long time ago, we were

little more than monkeys ourselves,

forced onto the savannah when climate change destroyed the forests

we'd long called home.

Evolution is born

out of necessity:

those primates who left the forests for the

savannah and didn't

repurpose nature to suit their needs didn't survive.

Our ingenuity

is an essential part of our existence - the predators in our early

days demanded it.

Creative

working-together

is what made humans

the

threat-neutralizing machines

we are today

If this creative

reshaping of nature is fundamental to

homo sapiens, then we can't

pick some moment in our past and say "there's where we made a wrong

turn".

-

Not when we learned to shape sticks into spears, or to speak

to one another using symbolic language.

-

Not with our domestication

of fire, or animals, or plants.

-

Not with the agricultural cultures

that rose up in the Fertile Crescent, nor the invention of

industrialization, nor the Information Age.

These are all

incremental consequences of our fundamental nature - without them

there simply would be no humans at all.

If there's never

been a version of "human" that didn't possess this fundamental

ability to transform nature, can we look to any other aspects of

ourselves as the source of our planetary woes?

I've come to believe

the fundamental issue - man's

original sin - runs even deeper: it's our past as chimps,

grazers of bountiful forests, that leads to the current

mass-extinction.

What brings us now to the brink of our own

destruction is the simple fact that we're born from a world of

plenty.

Our ancestors roamed

these trees,

picking fruit along

the way

Homo sapiens

is the result of an evolutionary system that rewarded

collective innovation.

By this ability, this

virtue in the

literal sense, we have taken over the world, outsmarting the

fiercest of predators and overcoming most obstacles of

nature. But for most of our history, that evolutionary

system hasn't demanded we learn how to thrive without

abundance.

Our environment has not required us to think

ecologically or develop the capacity to keep an ecosystem in

balance.

Those just

aren't skills most humans have had to develop in order to

survive.

And that's

where Mars comes in...

Elon

Musk says he wants to go

to Mars because of all the ways

that humanity on Earth can be destroyed.

Whether by global

thermonuclear war, planetary climate change, or some rogue

asteroid, there are just too many scenarios where we all end

up dead.

Mars, he argues, presents

an opportunity to safeguard the humans species by

backing up our DNA on a second planetary hard drive.

SpaceX:

salvation or just more of the same?

While this

argument seems reasonable, it's not what gets me so excited.

If our primary purpose for going to Mars is to preserve the

human species, I think I'd have to agree with my friend that

our efforts would be better directed towards fighting the

most likely existential threats back at home.

Why pour so

much energy into fuel-guzzling rockets when our real issues

are rockets and fuel-guzzling in the first place?

To me, what

makes colonizing Mars appealing is not the chance to back up

human beings, but

the opportunity to

give birth to an entirely new species,

much like what our move from the forests to the

savannah kickstarted nearly 2 million years ago.

Homo martis

Darwin's

theory of natural selection is perhaps best represented by

his finches - those sweet little birds he discovered in

the Galapagos.

Presumably all descendants of a common

ancestor, as they evolved from generation to generation in

their individual micro-ecologies, each version of the finch

became distinct.

Small,

environmentally-serving variances compounded over time to

produce something new and different on each island.

Darwin's finches - each

beak suited

to the particulars of

its corresponding environment

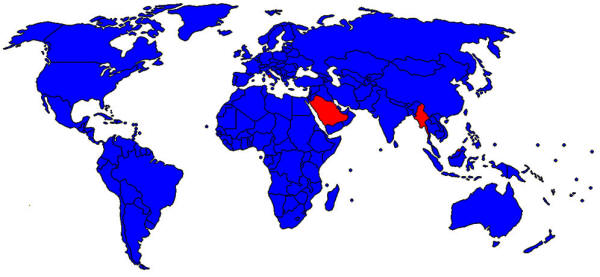

The

diversity of human forms tells a similar story.

Presumably

we all come from a common set of ancestors, but over time

races developed various physical differences in response to

different environmental demands around the world.

Like

Darwin's finches, our environment shapes who we become.

Homo sapiens

is the evolutionary product of

a fertile gem of a planet. Biologically speaking, our

relationship to Earth is that of an entitled child to an

exceedingly gracious parent.

But on Mars, an entitled child

can't survive. For humans to exist on Mars, they'll have to

carve gardens out of stone. Everything, from the air they

breathe, to the food they consume, would have to be

cultivated, grown, shaped, made.

For where Earth is Eden,

Mars is a wasteland.

Early Martian

colonization

would be no picnic

Musk talks

about backing up humans, but I suspect he recognizes that

once enough time has passed the two planetary species won't

be copies of one another.

As with the finches, given enough

time we can expect a pretty different kind of human to

evolve on the Red Planet compared to those on Earth.

The

distance between the two 'islands' is vast, and the

environments could not be more dissimilar.

If Martians

survived and managed

to terraform their red planet into blue

and green,

Bringing it home

Just as

finches and humans evolve, so too does human culture.

Undiscovered country

is breeding ground for

new ideas

And new

lands mean the opportunity for new cultures - the chance

to try out new ideas and new ways of working together.

It's

no coincidence that liberal democracy was first proven in

the Americas, for instance: here was a land without a

powerful ruling class to stand in the way of

experimentation.

On the

surface, at least,

nearly the entire planet is now

democratic

But new

ideas don't just grow where they're planted.

After North

America was transformed from a pioneer's wonderland into a

sandbox for liberal democracy,

the resultant culture spread

like a disease.

It wiped out monarchies and dictatorships

across the globe, invading host countries and transforming

them from the inside out.

Of course, the transformation has

been far from consistent - each land re-shapes Western

culture in a way that's more suited to its own environment

- but overall the impact has been tremendous:

It's easy to

get down

about the

state of the world,

but we've

made a lot of progress

The point

is not that Western civilization is

all that (we can

see from current events that it obviously isn't) but that

the culture born in North America eventually infected the

rest of the world. And the same thing can happen with Mars...

No matter

how badly homo sapiens

end up devastating the Earth, it's doubtful we'll be able to

produce anywhere near the level of desolation that

homo martis would

be born into.

Large-scale ecological wastelands will be her

native habitat.

She'll be a species with a planetary green

thumb.

Some assembly

...required

-

What kind

of impact might that kind of stewardship-oriented species

have on this planet?

-

How will the lessons we learn on Mars,

and the way that planet shapes us, change how we care for

life over here?

-

Might

homo martis be able to reverse the destruction of life

that has become a hallmark of

homo sapiens?

Of course,

we might not make it.

Mars is - in every imaginable sense

- an incredible longshot. And at the rate we're destroying

Earth our own civilization might collapse before we manage

to even get started.

But it's also a place where humans

might internalize what the majority of us have never learned

here:

how

to care for the world we're a part of.

And it

seems pretty clear we're going to have to master that if

mankind is going to survive at all...

|