|

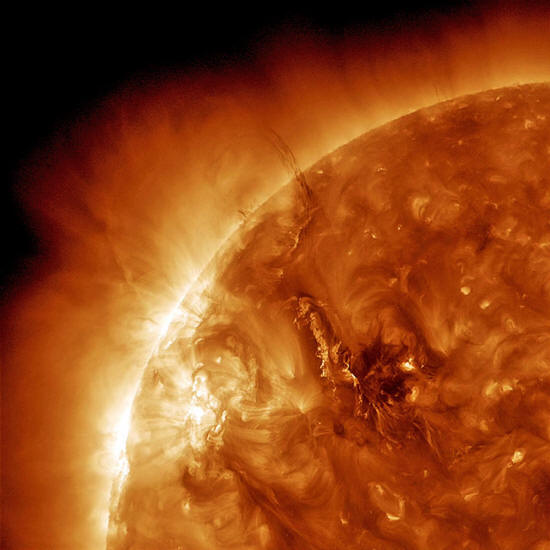

Spanish version generates the coiling and spreading wave-like action on the surface of the sun seen here. Sound waves created within the sun can reveal information about the magnetic activity

that

causes such prominences.

Scientists can study the sun's oscillations by listening to the frequencies (below video) that make up the sound signal, thereby learning something about the object making the sound:

Because the waves are generated by and pass through different sections of the sun, the wave frequency reveals clues about the inside of the sun and allows scientists to chart changes in the star's life.

Scientists from the Birmingham Solar-Oscillations Network (BiSON) at the University of Birmingham, in the United Kingdom, used the sun's sound waves to determine that one of its outermost layers may be growing thinner.

Yvonne Elsworth presented the new research at the National Astronomy Meeting at the University of Hull in the United Kingdom on July 4.

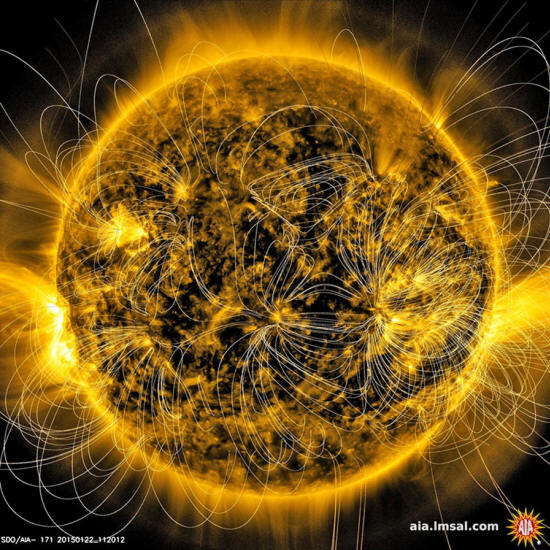

are

more concentrated in certain regions of the solar surface.

Tracking the waves

The sun, like Earth, has different layers.

One of the outermost layers is a few hundred kilometers wide, according to NASA, and is made up of plasma. The sun's plasma is a tremendously hot mix of separated electrons and ions, which means they are charged and naturally create magnetic fields.

Plasma churns and pulls in different directions around the sun, and the enormous heat produced by the nuclear fusion at the core plays along these currents to create magnetic fields.

So how does the sun produce sound?

The movement of the plasma creates sound waves. Patches on the surface of the sun oscillate up and down in 5-minute motions, NASA officials said in a reference page. These sound waves travel radially, meaning inward and outward.

The sound waves remain inside the sun, because the cavity of the star is constrained by the properties of its surface, thereby sending the waves downward.

Then, a change of direction caused by the wave's increased speed toward the middle of the sun makes it bounce back up toward the surface. When scientists study the frequency of these waves, they can tell a lot about the inside of the star, as well as learn about its magnetic field.

This is called helioseismology, and as the name suggests, it is similar to the concept of studying subterranean waves on Earth to predict earthquakes.

Solar sound waves are much too low for humans to hear, but they can be detected visually on the sun's surface and analyzed (above video). Visible features are caused by sound waves deep inside the sun's core, and they are simultaneously shaped by the activity near the solar surface.

Because these features are influenced by both the sun's core and the area near its surface, studying the features gives scientists a big picture look at the sun, researchers said in a statement about the new work.

This allows them to learn about the changing physical conditions of the sun, either at a given moment or over many years.

Observations by the Helioseismic and Magnetic Imager on NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory

show a two-level

system of circulation inside the sun.

Evidence of thinning

In the new research, the scientists found that the sun's outer layers were more sensitive to medium and higher frequencies, indicating that some areas of the solar surface have weakened, the researchers said.

The study tracked changes in the sun by looking at previous solar cycles of change, such as Cycle 22 which lasted from the years 1986 to 1996, and found that the oscillation frequencies were confined to a thinner layer than those previous cycles.

That means it has been more than 20 years since scientists have observed such a thin solar layer.

Factoring in observations from earlier technologies, the data suggests the sun has not had an outer layer this thin since over 100 years ago.

Therefore, researchers of the BiSON study believe this weakening phenomenon is an overall thinning of the layer, rather than just a normal part of the sun's 11-year cycle of activity.

When a solar cycle ends, it is called a solar minimum. The sun is approaching the end of Cycle 24 now, and will reach it around 2019.

By comparing findings of the current period of minimum activity with those of previous cycles, scientists can paint a picture of the changes in the sun over a span of decades, and sometimes centuries.

|