|

by Ben Potter

March 27,

2015

from

ClassicalWisdom Website

Nineteenth-century painting by Philipp Foltz

depicting the Athenian politician

Pericles

delivering his famous funeral oration

in front of the Assembly.

In Ancient

Greece, 'turannos' or 'tyrant'

was the phrase

given to an illegitimate ruler.

These usurpers

overturned the

Greek 'polis'

and often came

to power

on a wave of

popular support.

While Greek

tyrants were like

the modern-day

version

insofar as they

were ambitious

and possessed a

yearning for power,

not all of them

(the Greeks)

were butchers or

psychopaths.

Source

The lead-up to the Second World War was often referred to (in its

own time) as the Age of the Great Dictators.

The idea being that, even though the fledgling American experiment

was going rather well, not all democracies were pulling their weight

in the war of ideologies.

Emerging dictatorial governments in,

-

Spain

-

Italy

-

Germany

-

Russia,

...were getting their

respective nations back on track as Europe strived to recover from

its self-destructive, turn of the century warmongering.

The fact that these were dictators, men of the people, for the

people, instead of privileged, hereditary monarchs in charge of the

ship of state seemed like a natural and sensible step in the right

direction.

Though I hear the cry going up from all corners of cyberspace:

"Quit stalling.

What's this got to do with the Classics?"

Pray beat still,

impatient hearts.

The point is that, as hard as it is for us to imagine now,

dictatorships haven't always been seen as 'bad'.

It was only after the

fact that it was considered to be an undesirable form of government,

regardless of the personnel involved, and universally reviled

throughout civilized parts of the world.

And indeed this was true also in the ancient world.

Though it should be stressed that between then and now someone left

a red sock in with the 'dictatorship' wash and what came out in the

end wasn't exactly what went in.

For Romans, a dictator ('one who leads') was a politician/general, a

magistratus extraordinarius, who was given temporary, and not

quite absolute, power to perform a specific task, e.g. putting down

a rebellion.

But such a power was considered too dangerous to grant for any

conflict outside Italy, as a dictator would then be able to do as

they pleased away from the beady eye of the Senate.

Thus, as Rome expanded her empire and the Italian peninsula became a

land under no imminent threat, dictatorship fell by the wayside.

Though in 83 BC, after a 120-year hiatus, the victorious general

Sulla revived the power for a single year before retiring from

public life.

The purpose of this

was to re-codify the constitution following a series of civil

wars.

This move was roundly

mocked by the next man who took up the dictatorial gauntlet...

Gaius Julius Caesar.

As it became increasingly obvious that Caesar was not only the

dominant figure following the civil war of the 40s BC, but a cunning

and ruthless politician as well as a fine military strategist, the

Senate deemed it expedient to appoint him dictator... and

dictator again... and then dictator for ten years... and

finally, dictator for life.

However, life didn't last very long, only until 15th

March 44 BC, or the Ides of March.

Octavian Augustus

Despite going on to take many further powers and titles, Octavian

Augustus, the first truly absolute ruler of this new Rome, did

not dare to call himself 'dictator':

the word had by then

become poisonous...

And while the Romans had

a long history of viewing tyranny as an unpleasant

form of government (hence the Republic), it wasn't that way in

pre-Classical Greek thought... and

the memory of past Tyrants is illustrative of this.

For example,

Cypselus, a

tyrant of Corinth who came to power in 657 BC after ousting an

aristocratic family, was a popular and dynamic leader who

consolidated Corinthian interests abroad and made Corinthian

pottery dominant in the Greek marketplace.

Cleisthenes ruled Sicyon from c.600-560 BC and is

remembered best for his enduring tribal reforms rather than

anything insidious.

Polycrates of Samos (ruled c.538-522 BC) was a popular

and enlightened tyrant about whom Herodotus speaks well. His

public building works included aqueducts and temples which

reflected both his benevolence and piety.

Herodotus also suggests he may have been pretty humble

(well, for a tyrant anyway). Supposedly he threw his prized

possession, a bejeweled ring, into the sea in the hope of

avoiding the hubris of the overly successful. However, ill-omen

struck when a fish turned up with the ring inside it.

Polycrates and the Fisherman,

Salvator Rosa, 1664

Maybe not surprisingly, it was in Athens, the bastion of enduring

Greek thought, that tyranny finally developed the stigma it has

today.

Though, again, this was not initially the case.

Peisistratus, a relative of the much-lauded lawgiver Solon,

initially managed to install himself as tyrant in 561 BC, but was

only able to make the title stick in 546 BC.

From that point on a string of populist and cultural policies helped

to underpin his power.

He initiated a public building program, extended or created

festivals (including the dramatic festival, the Dionysia and an

Athenian 'Olympics', the Panathenaic Games), codified the works of

Homer and championed the causes of peasants and landowners.

Copper engraving of

Peisistratus,

1832

Indeed, Peisistratus was considered a model tyrant with almost no

connotations of the violent oppression the word conjures up.

Aristotle said of him:

"his administration

was temperate... and more like constitutional government than a

tyranny".

This is high and

significant praise indeed, as Aristotle and Plato

helped to popularize the idea that,

tyranny

was a base and unsatisfactory form of government in and of

itself...

Moreover, Peisistratus

had that luxury so few tyrants enjoy, to die a peaceful death.

Though the same cannot be

said of his son and joint-heir, Hipparchus.

He, along with his brother Hippias, continued their father's

work, but were met with strong opposition in the form of

Harmodius and Aristogeiton, the original Tyrannicides.

These men succeeded in killing Hipparchus in 514 BC, but Hippias

escaped the assassin's blade.

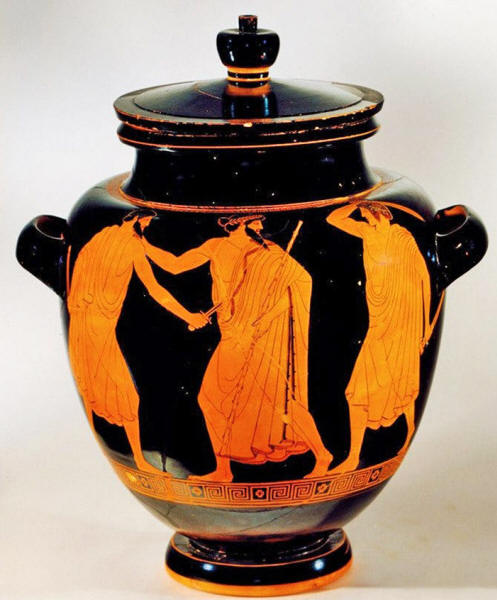

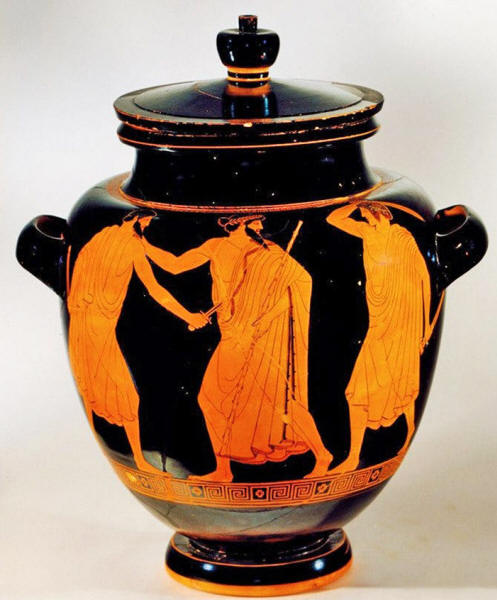

Vase depicting the

death of Hipparchus

Hippias' sole reign was, perhaps unsurprisingly given the

circumstances, violent and oppressive and many believe he became the

source of all our negative connotations associated to the word

'tyrant'.

For the Athenians this was certainly true.

Fortunately Hippias was removed from power in 510 BC, allowing the

noble Cleisthenes to initiate the reforms that gave birth to

Athenian democracy.

Tyranny never recovered...

From this point on

merely accusing someone of being tyrannical was enough to slur

them, it was no longer necessary to state why that was the wrong

way to be.

Thus a few final words on

the pitfalls of such a form of government shall be given to the two

men who, perhaps, did more than any other to show that tyranny's

dark underbelly was more than merely suspicious, but destructive and

pernicious.

And here I've saved the best, or at least most alarming, quote for

last:

"The tyrant must be

always getting up a war... in order that the people may require

a leader."

Plato

"Tyranny is a kind of monarchy which has in view the interest of

the monarch only."

Aristotle

"A tyrant, as has often been repeated, has no regard to any

public interest, except as conducive to his private ends; his

aim is pleasure."

Aristotle

"Dictatorship naturally arises out of democracy and the most

aggravated form of tyranny and slavery out of the most extreme

liberty."

Plato

|