|

from ScientificAmerican Website

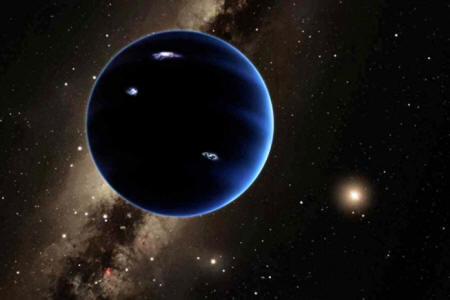

(Planet Nine = Planet Ten = Planet X = Nibiru) as an ice giant eclipsing the central Milky Way, with a starlike sun in the distance.

Neptune's orbit is

shown as a small ellipse around the sun.

Astronomers are homing in on the whereabouts of a hidden giant planet in our solar system, and could discover the unseen beast

in roughly a year. The hunt is on to find "Planet Nine" - a large undiscovered world, perhaps 10 times as massive as Earth and four times its size - that scientists think could be lurking in the outer solar system.

After Konstantin Batygin and

Mike Brown, two planetary scientists from the California

Institute of Technology,

presented evidence for its existence

this January, other teams have searched for further proof by

analyzing archived images and proposing new observations to find it

with the world's largest telescopes.

Many experts suspect that within as little as a year someone will spot the unseen world, which would be a monumental discovery that changes the way we view our solar system and our place in the cosmos.

He is just one of many scientists who

leapt at the chance to prove - or disprove - the team's careful

calculations.

Theoretically, though, its gravity should also tug slightly on the planets.*

With this in mind, Agnès Fienga at the Côte d'Azur Observatory in France and her colleagues checked whether a theoretical model (one that they have been perfecting for over a decade) with the new addition of Planet Nine could better explain slight perturbations seen in Saturn's orbit as observed by Cassini.*

Without it, the other seven planets in the solar system, 200 asteroids and five of the most massive Kuiper Belt objects cannot perfectly account for it.*

The missing puzzle piece might just be a

ninth planet.

They found a sweet spot - with Planet Nine 600 astronomical units (about 90 billion kilometers) away toward the constellation Cetus - that can explain Saturn's orbit quite well.*

Although Fienga is not yet convinced that she has found the culprit for the planet's odd movements, most outside experts are blown away.*

Gerdes agrees:

The good news does not end there.

If Planet Nine is located toward the constellation Cetus, then it could be picked up by the Dark Energy Survey, a Southern Hemisphere observation project designed to probe the acceleration of the universe.

Although the survey was not planned to search for solar system objects, Gerdes has discovered some (including one of the icy objects that led Batygin and Brown to conclude Planet Nine exists in the first place).

Laughlin thinks this survey has the best immediate chance of success. He is also excited by the fact that Planet Nine could be so close.

Although 600 AUs - roughly 15 times the average distance to Pluto - does sound far, Planet Nine could theoretically hide as far away as 1,200 AUs.

And the Dark Energy Survey is not the only chance to catch the faint world. It should be possible to look for the millimeter-wavelength light the planet radiates from its own internal heat.

Such a search (Cosmologists in Search of Planet Nine - The Case for CMB Experiments) was proposed by Nicolas Cowan, an exoplanet astronomer at McGill University in Montreal, who thinks that Planet Nine might show up in surveys of the cosmic microwave background (CMB), the pervasive afterglow of the big bang.

Already, cosmologists have started to comb through data from existing experiments, and astronomers with many different specialties have also joined in on the search.

In the meantime Batygin and Brown are proposing a dedicated survey of their own.

In a recent study (Observational Constraints on the Orbit and Location of Planet Nine in the Outer Solar System) they searched through various sky maps to determine where Planet Nine cannot be.

The zone where the planet makes its farthest swing from the sun as well as the small slice of sky where Fienga thinks the planet could be now, for example, have not been canvassed by previous observations.

To search the unmapped zones, Batygin and Brown have asked for roughly 20 observing nights on the Subaru Telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawaii.

If they do, Brown is convinced he will have his planet within a year.

But Laughlin takes it a step further:

We now have another opportunity to see one of the worlds of our own solar system for the first time.

* Editor's Note (April 08, 2016): The headline and asterisked sentences in this story were edited after its original posting to correct an error.

The original stated that perturbations

in the Cassini spacecraft's orbit around Saturn could be caused by

Planet Nine. It is not Cassini's orbit, however, but perturbations

of Saturn's orbit around the sun that may be explained by the

presence of Planet Nine.

'Super Earth' Lies

beyond Pluto from ScientificAmerican Website

Astronomers have found compelling hints of a huge, unseen world that may reside in the murky reaches of the Kuiper Belt

Thanks largely to the space-based Kepler Mission, astronomers have identified about 2,000 new worlds, orbiting stars that lie tens or even hundreds of light-years from Earth, in the last two decades.

Collectively, these are scientifically important, but with so many in hand no single addition to the list is likely to be much of a big deal. But a new planet announcement today from the California Institute of Technology is a very different proposition, because the world it describes does not circle a distant star.

It is part of our own solar system - a place you

would think we had explored pretty well by now.

The scientists infer its presence from anomalies in the orbits of a handful of smaller bodies they can see.

The object, which the researchers have provisionally named "Planet Nine," comes no closer than 30.5 billion or so kilometers from the sun, or five times farther than Pluto's average distance.

Despite its enormous size, it would be so dim, the

authors say, that it is unsurprising that nobody has spotted it yet.

But the evidence is strong enough that other experts are taking very serious notice.

David Nesvorny, a solar system theorist at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), in Boulder, Colo., is impressed as well.

Strange orbits

In 2014 Chad Trujillo and Scott Sheppard, of the Carnegie Institution for Science, argued in Nature (A Sedna-like Body with a Perihelion of 80 Astronomical Units) that their own discovery of a much smaller object, called 2012 VP113, along with the existence of a handful of previously identified bodies in the outer solar system, hinted that there might be something planet-size out there.

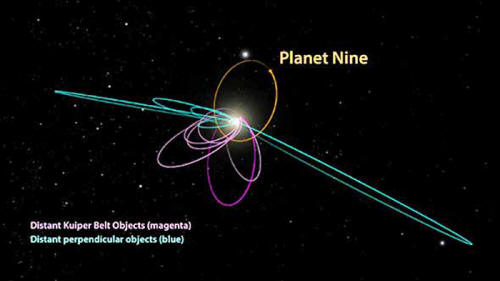

The evidence lay with their orbits, specifically with an obscure parameter called the "argument of perihelion" - the relationship between the time a body makes its closest approach to the sun and the time it passes through the plane of the solar system.

The objects Trujillo and Shepherd identified all had uncannily similar arguments of perihelion, which could mean they were being shepherded by the gravity of an unseen world.

Several groups did, and agreed that the case for a hidden planet was plausible but still quite speculative.

The new analysis strengthens that case dramatically, however. The similarity of the arguments of perihelion turns out to be "just the tip of the iceberg," Batygin says.

The first thing he and Brown did, he says, was to analyze Trujillo and Sheppard's data with entirely fresh eyes.

In other words, they point in the same direction. That outcome was not guaranteed; two bodies can have similar arguments of perihelion even if their orbits are not otherwise physically similar.

But when Brown and Batygin plotted the orbits of those outer solar system objects, they noticed that their highly elliptical orbit shapes were closely aligned.

The directionality of the orbits was an even stronger hint that something was physically herding these distant objects.

So they examined the most likely alternative - that the Kuiper Belt of icy objects beyond Pluto had formed all of its bodies into a clump naturally, much as galaxies pulled themselves into shape gravitationally out of the cosmic cloud of gas that emerged from the big bang.

The problem with that scenario, the authors realized, was that the Kuiper Belt lacks the mass to make it happen. When the scientists turned to the "crazy" notion of a planet, however, their simulations generated just the right kind of aligned orbits.

They also revealed something else:

Sure enough, observers have spotted a half dozen or so objects just like this and nobody had come up with a good explanation of how they might have gotten there.

Now Batygin and Brown's simulation was providing one.

Super Earth

Its most probable orbit is a highly elongated one that brings it to within 35 billion kilometers of the sun at the closest ("that's where it does all the damage," Brown says) and between three and six times as far away at its most distant.

Even at that enormous distance, Planet Nine could in principle be spotted with existing telescopes - most easily with the Japanese Subaru Telescope in Hawaii, which not only has a huge mirror for trapping faint light but also a wide field of view that would allow searchers to efficiently scan big swaths of sky.

Until they actually see it, astronomers cannot say definitively that Planet Nine is real.

The orbital alignment is genuine, he acknowledges.

Overall, however, planetary scientists are clearly thrilled by the prospect that we might be on the verge of such a major discovery.

The mood of the astronomical community is perfectly captured, Greg Laughlin says, by something British astronomer John Herschel said to the British Association for the Advancement of Science in a talk on September 10, 1846.

Just two weeks later Neptune was discovered, right where the theorists' calculations said it should be.

|