|

|

|

by Dr. Pat Hanratty July 07, 2020 from Ancient-Origins Website

Professor Charles Hapgood believed strange, unexplained maps were signs of a long-forgotten civilization of ancient sea kings. Source: Freesurf / Adobe Stock

The evidence, he said, indicated that some ancient people explored Antarctica when its coasts were free of ice.

It is clear too that they had an instrument of navigation for accurately determining longitudes that was far superior to anything possessed by the peoples of the ancient, medieval, or modern times until the second half of the 18th century.

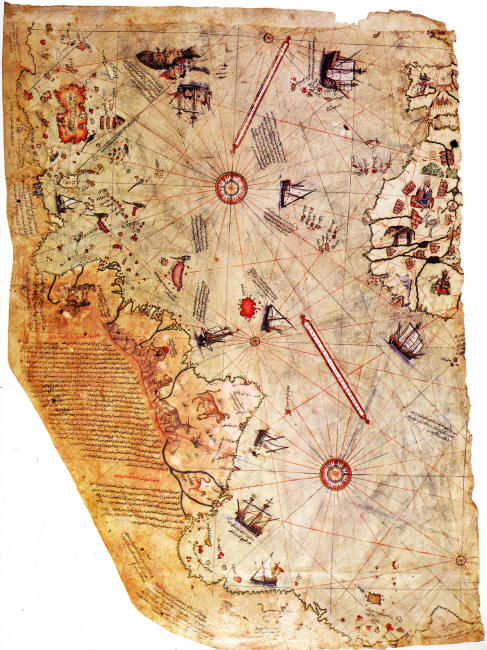

Mallory had come across a copy of the Piri Reis Map, a world map compiled in 1513 by the Ottoman admiral and cartographer, Piri Reis. He said publicly that the map seemed to show Antarctica, before it was discovered, and, furthermore, the coast seemed to have been mapped when it was free of ice.

In addition, Mallory's

opinion had been endorsed by the directors of the astronomical

observatories at Boston College and Georgetown University.

This was most remarkable,

for the navigators of the 16th century had no means of

finding longitude except by guesswork.

(Public

Domain)

Antarctica is actually two large bodies of land,

However, when we refer to

Antarctica as a continent, we are referring to Greater Antarctica,

which is roughly the size of the continental United States.

The report showed there was high correlation between Antarctica under the ice with large portions of the map.

The maps that Hapgood studied were portolano, or port to port, maps.

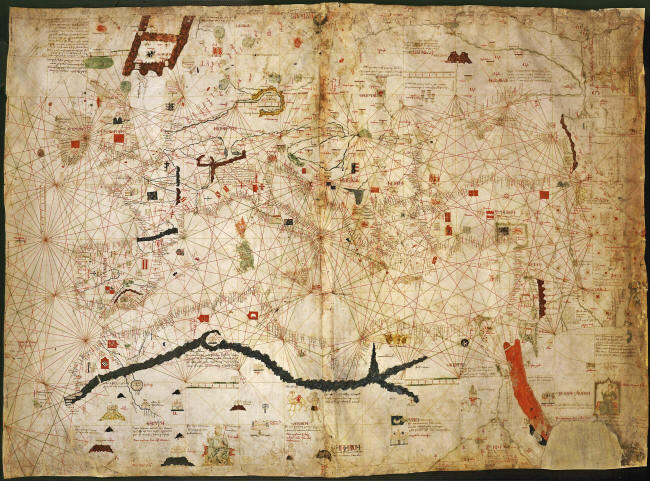

1439 portolan chart by Gabriel de Vallseca (Museu Maritim, Barcelona).

( Public Domain )

Consulting a

mathematician, he learned that the projections on the map had been

made by plane trigonometry. In addition, Hapgood found that some of

the positions on the Piri Reis Map were very accurate, and some were

far off.

He discovered that the

map was a composite, made by piecing together many maps of local

areas (perhaps drawn at different times by different people), and

that the errors had been made in combining the original maps.

For longitude, early ocean navigators had to rely on dead reckoning, the process of calculating one's current position by using a previously determined position, or fix, and advancing that position based upon known or estimated speeds over elapsed time and course.

This was inaccurate on

long voyages out of sight of land and these voyages sometimes ended

in tragedy as a result.

This was known as running

down a westing, if westbound, easting, otherwise.

This increased the

likelihood of short rations, which could lead to poor health or even

death for members of the crew due to scurvy or starvation, with

resultant risk to the ship.

A suitable one was eventually built by Yorkshire carpenter John Harrison, using his marine chronometer.

Chronometers such as those invented by Thomas Earnshaw were in general nautical use until the middle of the 19th century.

However, they remained

very expensive and other methods were used instead. Harrison's Chronometer H5 of 1772, now on display at the Science Museum, London. (Racklever /CC BY SA 3.0 )

Redrawing the map to account for these errors, Hapgood and his students came to a startling discovery:

Hapgood concluded that errors in the Piri Reis Map were due to mistakes in its compilation, presumably in Alexandrian times, and derived from ancient source maps.

This agrees with Peter

Tompkins, who, in his book Secrets of the Great Pyramid, suggests

that the Alexandrian geographers did not understand the information

they were handling, which was based on an advanced science that

preceded them.

This is amazing when one considers that Columbus, in 1492, made serious mistakes in finding latitude, and, of course, had no way of determining longitude, resulting in over a 1250-mile (2011.68 km) miscalculation of his location when he arrived at San Salvador in the Caribbean.

There are suggestions,

however, that Columbus had maps of Cuba before his first voyage.

This contains the implication, of course, that spherical trigonometry must have been known ages before its supposed invention by Hipparchus in the second century BC.

It also raises another question:

It seems that perhaps we can...

Since the Greeks did not

understand this, they distorted the information handed down to them.

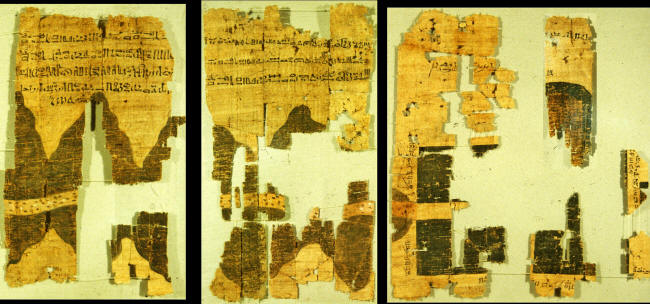

Egyptian Turin papyrus map. Public Domain )

Hapgood concluded that the ancient Egyptians had more advanced science than the Greeks.

For instance, a point of

considerable interest is the shape of the

Atrato River.

This suggests that

somebody explored the river to its headwaters in the western

cordillera of the Andes sometime before 1513. There is no known

record of such an exploration.

However, Hapgood did talk about "a great island" on the Piri Reis Map in the Atlantic Ocean.

Since it was so carefully drawn, and since Hapgood believed this island would have been ideally suited by climate and location for agricultural and commercial development and as a base for navigation, he concluded that this may have been the home for the people who developed the maps.

The mountain ranges shown were individualized, some being on the coast and others inland.

The map showed rivers

flowing into the sea, suggesting the coasts may have been ice free

when the original map was drawn.

He concluded that as the

ancients had a correct idea of the size of the Antarctica Continent

suggests that they may have had a correct idea of the size of the

earth as well; knowledge that is reflected in the Piri Reis Map.

This map showed numerous

points on the continent of Antarctica clearly.

(Public

Domain)

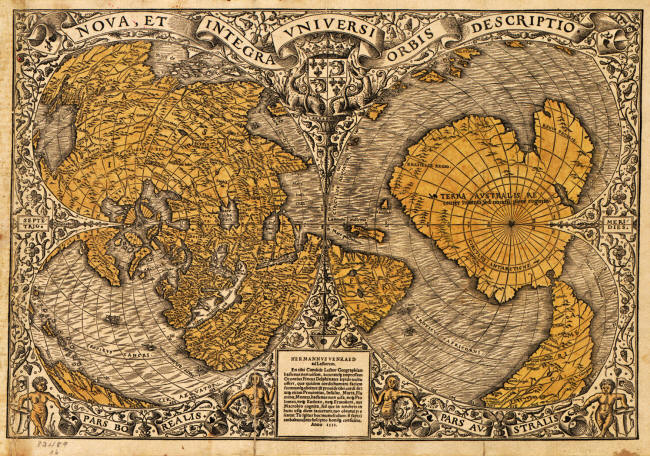

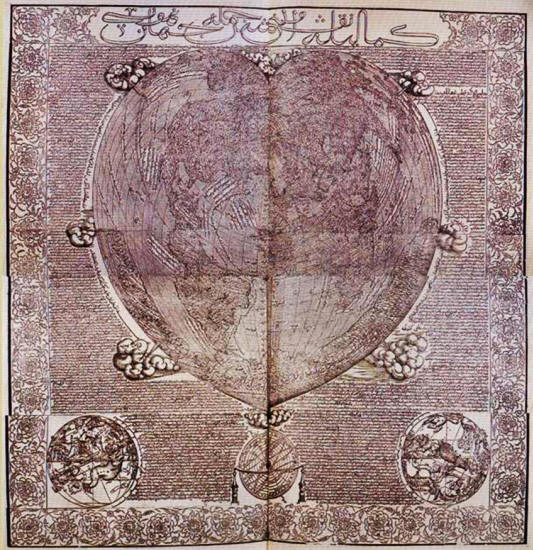

Mercator complied his Atlas in 1538 and, as maps were being drawn by early explorers, revised this in 1569 to reflect changes reported by them.

Hapgood states:

Hapgood suggested that the first map depended on ancient sources while the latter map relied on feedback from early explorers, who had no accurate longitude and so could merely guess at the trends of coasts.

According to Hapgood, the map reflects accurate information on the latitudes and longitudes of places scattered all the way from Galway in Ireland to the eastern bend of the Don in Russia.

A.E. Nordenskiold, in his nineteenth century book, The Voyage of the Vega Round Asia and Europe, had earlier concluded that no medieval mapmaker could have drawn this map.

Hapgood believed that the

mapmaker used spherical trigonometry in the compilation of this map.

used spherical trigonometry in the compilation of the Dulcet Portolano Map of 1339. (Public Domain)

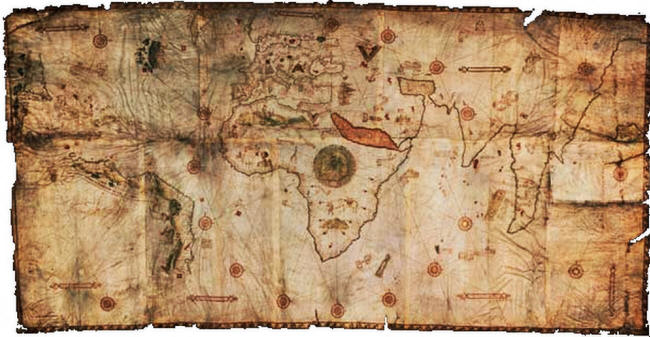

The De Canerio Map of

1502

According to Hapgood, the average error in latitudes of 11 places,

...was only one half of one degree.

The longitudinal distance

between Gibraltar was accurate, proportional to the latitude,

suggesting there may have been no significant error in the original

source map as to the size of the earth.

He concludes that this

reflects the mapmaking of an advanced ancient culture.

De Canerio Map. (Public Domain)

Strangely, it shows Asia and Alaska joined together. It does not show Beringia, the land bridge across the Bering Strait, which was submerged at the end of the last Ice Age.

Hapgood speculated that

the Hadji Ahmed map was based on far earlier maps that date back to

a long-forgotten civilization of 'ancient sea kings.'

He addressed many more specific criticisms, and also pondered:

Furthermore, the Hapgood team identified 50 geographical points on the Finaeus map, as re-projected, whose latitudes and longitudes were located quite accurately... some of them quite close to the pole...

There are other factors, too.

(Public

Domain)

It begs the question:

|