|

|

|

by James Corbett September 2014

from

CorbettReport Website

September 19, 2014

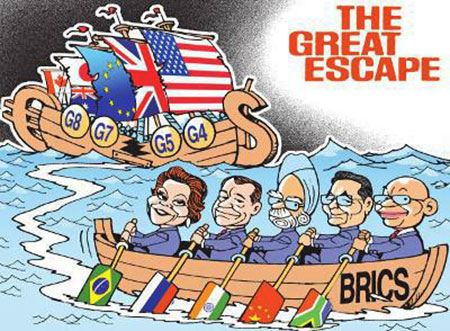

As many have heard by now, the leaders of the so-called BRICS nations - Brazil, India, China, Russia and South Africa - used the occasion of the 6th BRICS Summit in Brasilia, Brazil to announce the creation of the long-awaited BRICS Development Bank.

Formally the "New Development Bank" (NDB), it will be based in Shanghai and capitalized with an initial $10 billion in cash ($2 billion from each of the five founding members) and $40 billion in guarantees, to be built up to a total of $100 billion.

Immediately, the press began touting the new bank as a potential rival to the current IMF/World Bank system of infrastructure development and poverty reduction in the third world.

The World Bank, for its part, is downplaying the rivalry, with World Bank President Jim Young Kim openly welcoming the bank at a recent meeting with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

But all of this talk about a potential rival to the IMF and World Bank have exposed the general public's ignorance about what exactly these institutions are and what they do.

While most are familiar with the IMF and its predatory lending practices (and those who aren't are encouraged to acquaint themselves with the "IMF riot" strategy that was developed in the third world and is now being imported to Europe), the World Bank is less scrutinized and less well understood.

What is it, what does it do, and why is it important for the BRICS to challenge its hegemony in the development and poverty reduction arenas?

For the answer to that, we'll need to examine the World Bank's history, both the official history that it touts to the outside world and the real history of its part in plundering the developing world that it is supposedly there to help.

The Official Story

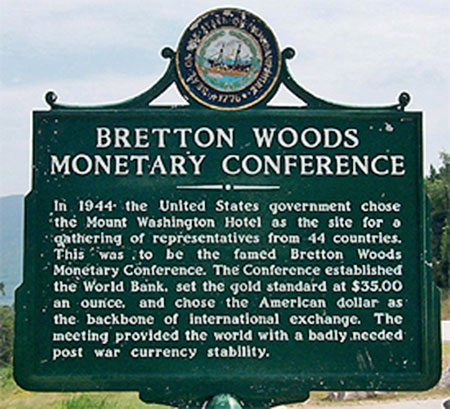

The World Bank was born along with the IMF at the 1944 Bretton Woods conference that decided on the financial architecture of the post-WWII world, only at that time it was known as the "International Bank for Reconstruction and Development" and was concerned primarily with post-war reconstruction of Europe.

After the implementation of the Marshall Plan in 1947, however, its focus shifted to the non-European world where it provided development loans targeted at helping developing countries create income-generating infrastructure (power plants, seaports, highways, etc.).

From the very beginning there have been questions about the overlap of the IMF and World Bank's respective roles.

Both are committed, according to the IMF website, to "raising living standards in their member countries," but the IMF is financial in nature, concentrating on short and medium-term loans to help countries meet balance of payment needs, while the World Bank is fundamentally a development institution, focusing on technical and financial support for specific projects or sectoral reforms.

Part of the confusion is linguistic; at the first ever meeting meeting of the IMF the "father" of Bretton Woods, John Maynard Keynes (who else?), confessed he thought the Fund should be called a bank and the Bank should be called a fund.

Nevertheless, the monikers have stuck and the World Bank and IMF continue to talk the talk of global infrastructure development and poverty reduction.

Since the World Bank pivoted away from Europe to concentrate on the developing world in the late 1940s, it has lent more than $330 billion on infrastructure development projects.

It currently boasts $232.8 billion in total subscribed capital, overseeing $358.9 billion in total assets.

The World Bank concentrates its lending on creditworthy governments of developing nations, and splits its lending activities between the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) and the International Development Association (IDA).

The IBRD generally provides 12-15 year loans at slightly above market rates to countries with per capita GDPs above $1305. The IDA, meanwhile, provides interest-free 35 to 40 year loans to countries with per capita GDPs below the $1305 mark.

Unlike the IMF, which is funded by quota subscriptions from member countries, the World Bank finances its lending by borrowing on the international bond market. As a result, for the first decades of its existence the World Bank was concerned with building up its reputation as a lender and establishing its own creditworthiness.

Until 1968, the Bank was a relatively small institution with less than 1000 employees concentrated in Washington that concerned itself almost exclusively with loans designed to finance transportation and energy infrastructure projects.

When JFK/LBJ Secretary of Defense and unconvicted war criminal Robert McNamara took over as president in 1968, however, he began a radical repositioning of the Bank and transformation of its aim, scope and practices.

Over his 12 years at the helm of the Bank, McNamara greatly expanded its lending activities, shifting the aim of that lending toward agricultural reform and literacy initiatives, as well as the building of schools and hospitals.

During this period the Bank's treasurer, Eugene Rotberg, increased the Bank's capital by going beyond the established developed world banks that had been its primary funding source and tapping into the global bond market.

In the 1980s the bank began to press so-called "Structural Adjustment Programs" on loan recipients, including mandates to devalue currencies or reduce government spending in various areas, as pre-conditions for lending.

The Bank also began providing lending to help governments service the debts they had racked up in previous rounds of lending.

After the Bank came under increasing scrutiny (and protest) in the 1990s and early 2000s, it has adjusted its policies and practices to address its critics. It now touts environmental responsibility in the infrastructure projects it provides loans for and places greater emphasis on the goal of promoting economic engagement by the poorest people in its target countries.

As a result, the World Bank now claims to focus on the 'eradication' of hunger, gender 'equality,' environmental sustainability, maternal health and child mortality, communicable disease prevention, and universal primary 'education' in its target countries.

The Real Story

As readers of these pages will no doubt be aware, there is of course more to the story than that glossy, PR-friendly official story would have us believe.

The period of McNamara's stewardship from 1968-1980 was instrumental in shaping the institution that we know (or should know) today:

The larger capital that was raised during his tenure was used to expand the bank's lending activities, and those expanded loans kicked off the era of the third world debt crisis, including a period from 1976 to 1980 where developing world debt rose on average 20% per year.

As journalist John Pilger noted in his powerful documentary, "War By Other Means," released back in 1991:

War by Other Means

The process by which these loans are made and the funds distributed to their recipients has long been rife with waste, corruption and fraud.

Even in the best circumstances, the types of projects that the Bank concerned itself with in its early days, infrastructure projects focusing on energy and transportation, served to primarily enrich those who were already the richest in the target countries, the friends and cronies of the corrupt rulers whose business interests could make use of such innovations.

At its worst, the Bank has been used to underpin the rule of corrupt and tyrannical leaders and force entire nations into debt slavery.

This process was described most famously by former insider and self-described "economic hitman" John Perkins, who wrote his "Confessions of An Economic Hitman" to shed light on the means by which the seemingly benevolent IMF/World Bank system is used to oppress and plunder the very populations it is designed to enrich.

In his book, "The Globalization of Poverty and the New World Order," Professor Michel Chossudovsky of the University of Ottawa provides extensive documentation of precisely how this process has functioned over the years through the Structural Adjustment Loan and Sector Adjustment Loan programs at the World Bank's disposal.

This documentation includes details of the Bank's oversight of the build-up of Rwanda's military budget in the run-up to its bloody internal war of 1994, the Bank's own admission of how its loan-dictated deregulation of Vietnam's grain market led to widespread child malnutrition in the country, and the World Bank's contribution (in conjunction with the IMF) to the unprecedented plundering of Russia that took place in the wake of the Soviet collapse.

The World Bank, despite its friendly exterior and the lofty platitudes its proponents spout in its defense, continues to undergird a system of exploitation and debt enslavement of developing countries.

For half a century, the Bank has been responsible for the furtherance of a Pax Americana built not upon peace, prosperity and free trade but violence, debt and enforced servitude.

The Rest of the Story

…But now along comes the New Development Bank promising an alternative to the World Bank hegemony.

Unlike the Structural Adjustment Loan regime of the World Bank, the NDB is promising to provide loans with no strings attached; the BRICS have no interest in telling loan recipients how to run their country.

The answer to these questions constitute what Paul Harvey would call in his trademark drawl, "the rest of the story…" and we will explore that story here below...

September 29, 2014

The World Bank itself is a body that

ostensibly provides long-term low interest or no interest loans

secured on the global bond market to fund sectoral reforms and

infrastructure development projects in some of the poorest countries

in the world.

These impossible debt obligations are then used to give the Bank leverage over the developing world economically and geopolitically.

What's more, both the IMF and the World

Bank have historically been controlled by the US and Europe, and

clamors for reform in governance from the developing countries have

fallen on deaf ears.

The development was by no means surprising: the idea for a BRICS development bank has been bandied about for years now and was written about in the pages of this newsletter extensively last year.

Nor does it represent (at least at this point) a fundamental challenge to the World Bank or IMF's dominance; neither the NDB's $50 billion USD in subscribed capital nor the CRA's $100 billion liquidity pool come close to the World Bank's $232.8 billion in subscribed capital or the IMF's $755 billion in liquidity ($1.4 trillion if you include emergency funds).

Neither do they have the infrastructure

yet in place to coordinate and deploy these funds, nor a track

record of working with the world's poorest countries to ensure that

funds reach their intended targets and not the Swiss bank accounts

of corrupt politicians and middlemen.

Still, there is something of a revolutionary feel to the obligatory pictures of the smiling BRICS leaders coming out of this year's summit.

This year the smiles do not seem quite as forced. Perhaps they even seem a little self-assured.

It may be a baby step, but after all it is a step toward a world where the poorest countries do not have to turn cap in hand to the IMF or World Bank for financial aid.

To answer these questions, we must first examine the institutions in question.

The Basics

Under the terms of the Agreement signed by the BRICS leaders at Fortaleza, the New Development Bank's mandate is to,

To accomplish this goal they will,

The initial subscribed capital of $50 billion will come from initial payments of $10 billion from each of the five BRICS members.

Total authorized capital of the Bank will be $100 billion. Membership of the bank will be open to all members of the United Nations and each members' voting power will be equal to its subscribed shares in the Bank's capital stock.

The Bank will be headquartered in Shanghai and its governance will consist of a Board of Governors, a Board of Directors and a President.

The Contingent Reserve Arrangement, meanwhile,

Its initial $100 billion in committed resources will come in tranches:

Governance of the CRA will consist of a Governing Council including one Governor and one Alternate Governor appointed by each of the five parties and a Standing Committee consisting of one Director and one Alternate Director appointed by each party.

The Arrangement's two main instruments will be a liquidity instrument for providing funds in response to balance of payment problems and a precautionary instrument for permitting access to funds ahead of anticipated balance of payment problems.

A Global Power Struggle?

The agreements for both the NDB and the CRA take pains to point out that they are meant as a "complement [to] existing international monetary and financial arrangements" rather than as competition to them.

And the World Bank has formally welcomed the announcement of the NDB, with World Bank President Jim Young Kim telling reporters at a recent press conference with Indian Prime Minister Modi,

But behind the polite words and 'we're all working toward the same goal' rhetoric is the cold fact that the developing world has been increasingly vocal about their interest in World Bank reform in recent years and specific complaints from the BRICS nations themselves over the strings that are inevitably attached to World Bank lending.

It is also perhaps significant that all of the BRICS nations except China will be paying more into their capitalization of the NDB than they do to the World Bank.

Although much talk has been made about how the BRICS are attempting to subvert the dollar's hegemony as the world reserve currency, that is not the case with these institutions, at least not at this point.

All of the capitalization payments and fund commitments in the agreements for the NDB and CRA are explicitly denominated in,

The main competition that many are expecting from the NDB as opposed to the World Bank is that there are expected to be far fewer (if any) conditionalities attached to NDB lending.

As we saw last week the Structural Adjustment Programs of the IMF and World Bank require a whole series of political and economic reforms dictated by Washington and its cronies before developing countries can qualify for development funds.

Now members of globalist institutions like Matt Ferchen of the Carnegie Tsinghua Center for Global Policy are openly fretting about the possibility that NDB funding will undermine this structure:

For those who understand that the IMF/World Bank system is and has been used to subjugate debtor nations and impose the will of the Western powers on those countries, this seems like a potentially transformative moment.

'Good' Globalization vs. 'Bad' Globalization

Like with so many other situations, we must be careful not to fall into the trap of believing that the only alternatives that are being presented to us are the only alternatives that are possible.

In this case, it seems that we are being presented with the choice between supporting a development paradigm led by the 'bad' globalists of the IMF/World Bank crowd that seek to control other countries through financing and the 'good' globalists who are selflessly looking to spur development for the good of humanity.

This is just such a false choice.

No, the 'good' globalization/'bad' globalization here seems like a ruse to further globalization.

Whether the world comes to accept a greater reliance on and submission of sovereignty to globalist institutions led by the West or institutions led by the BRICS countries does not seem to be a genuine choice.

It should first of all be noted that the urge to assume that developing nations cannot possibly find solutions to their own infrastructure and development problems without the aid of the rich global power players is not only paternalistic and patronizing, but contra-indicated by the evidence at hand.

The answers to these questions, all easily enough documentable, speak for themselves.

Also, it shows a profound lack of imagination to believe that funding can only come through mega-grants delivered by bodies with hundreds of billions of dollars at their disposal.

In recent decades the concept of microcredit has transformed our understanding of what is possible in terms of funding business and enterprise in the developing world, and it is currently challenging assumptions that infrastructure like affordable housing and sanitation systems can only be provided by the "grant aid lottery" of the World Bank (or NDB).

Local communities know best what local needs are and how local manpower, resources and services can be organized to meet those needs.

Granting bodies in Washington or Shanghai cannot possibly be expected to have that type of knowledge, or expect that throwing dollars at these problems will achieve the same results as providing small-scale, goal driven aid for specific local projects created and run by local community organizations.

It is not a question of 'good' global banks vs. 'bad' global banks.

It is global banks versus the people, as it always has been, and when we understand the situation from that perspective the sheen comes off of the ballyhoo surrounding the New Development Bank.

Whither the NDB?

Before anyone gets too carried away with speculation about the NDB and the CRA and their likely role on the world stage, it would be good to conduct a brief reality check.

There was another announcement of another alternative development bank just a few short years ago that received a similar amount of coverage and hoopla at the time that turned out to be all talk and no action.

Remember the Bank of the South? Neither do most of the people who wrote about it at the time, and yet it seemed like a major development when it occurred.

That the BRICS are serious about following through with the NDB and the CRA is not in doubt, but that they can keep these organizations together and working toward a unified vision is very much doubtful at this moment. Internal divisions within the BRICS delayed the creation of the bank for years and even now tensions continue between the members.

Brazil and China, for example, remain locked in disputes over China's economic relation to the South American country; Brazil accuses the rising dragon of plundering their resources and dumping cheap manufactured goods on the country in return.

China and India have also butted heads over control of the NDB's policies and vision, and there is ongoing concern about whether South Africa will be able to live up to its financial obligations in these institutions.

All of this being said, the bank is hoping to make its first loan in 2016. When that happens, there will be no doubt that we will be living in a different world.

The question is whether it will be a better one.

|