by F. William Engdahl

15 November 2011

from

VoltaireNetwork Website

Through the new North

Stream and South Stream pipeline systems, Russia is clearly

redrawing the energy map of Europe.

Its status as the pre-eminent

supplier of natural gas-hungry European countries, including

major NATO member states, is certain to significantly

transform future east-west relations.

As expounded by this author,

energy is the lever for Russia’s return to the world stage

and for checkmating Washington’s NATO encirclement strategy.

The new Nord Stream gas pipeline was officially

opened in the North German town of Lubmin.

German Chancellor Merkel, Russian President

Medvedev, Dutch Prime Minister Rutte,

French Prime Minister Fillon and

European Commissioner Oettinger attended the opening.

On November 7 the first of two pipelines for Nord Stream, the huge

Russian-German gas pipeline project, began delivery of gas.

The event was no

minor affair.

German Chancellor Merkel and Russian President

Medvedev along

with the prime ministers of France and the Netherlands and the EU Energy

Commissioner formally opened the first of two

1224-kilometre pipelines at Lubmin in northern Germany, beginning delivery of the first gas direct from

Russia’s Yuzhno-Russkoye gas field in Siberia to Germany.

Nord Stream was not cheap. It cost a total of more than $12 billion for the

complex 760 mile long undersea pipeline through the Baltic Sea from Vyborg

near Russia’s St Petersburg to north eastern Germany.

It was laid in remarkable time and with

extraordinary environmental precautions to insure protection of sea life, a

precondition set by several EU Baltic countries. When the second pipeline is

finished in late 2012, Nord Stream will be able to deliver 55 billion cubic

meters of Russian gas a year, almost ten percent the entire EU annual gas

consumption, or roughly one third the entire current gas consumption of

China.

Nord Stream estimates it will provide enough energy to fuel 56 million West

European households. With current EU political decisions over reducing CO²

“carbon footprint” emissions, the Russian gas giant argues its natural gas

gives 50% less CO² than rival coal plants at as much as 50% greater energy

efficiency.

Even if Moscow is being more than somewhat opportunist and is not convinced

about the

shoddy science of global warming, Gazprom does not hesitate to use

this as a shrewd political selling point.

The EU is going for natural gas energy big time

and Moscow intends to be a major, if not the major beneficiary of that push.

In addition to delivering Siberian gas to Germany, Nord Stream will deliver

to,

-

the United Kingdom

-

Denmark

-

the Netherlands

-

Belgium

-

France

-

the Czech Republic

Moscow appears to hold a winning hand in the one important non-military

lever it has to tip the global geopolitical balance of power in its

direction and away from Washington’s overwhelming dominance.

Oil and natural

gas are at the heart of the strategy. For some months Russian production of

crude oil has surpassed Saudi Arabia’s to be the world’s largest oil

producer with over 10.3 million barrels daily, nearly one million barrels

more. [1]

And in terms of known reserves of natural gas

Russia is far away the world leader according to industry data.

Russian natural gas has increasingly been the foundation for a brilliant

series of Russian energy geopolitical initiatives for several years.

Gazprom,

a closely-held state company, is the centerpiece of this energy strategy.

To counter the eastward march of NATO into countries of the former Warsaw

Pact such as Poland, the Czech Republic or Romania and the various US

attempts to lure Ukraine and Georgia into NATO, Russia’s Vladimir Putin,

both as President and more recently as Prime Minister, has used the economic

lever of Gazprom.

With its enormous gas resources Russia seeks to

win stronger economic ties in western Europe, thereby hopefully neutralizing

somewhat the potential military strategic threat from the NATO encirclement.

No country has been more the focus of this

Russian pipeline diplomacy than former wartime foe Germany where Nord Stream

lands.

North Stream map

The undersea route across the Baltic to Germany

was chosen by a German-Russian consortium including Gazprom with 51% and the

German chemicals group BASF Wintershall and E.ON Ruhrgas of Germany each

today with 15.5% share, giving the German-Russian partners a dominating 82%

control.

Further adding to the political support from key

EU countries, later they were joined by N.V. Nederlandse Gasunie and

France’s GDF Suez which each own a 9% share.

The Baltic undersea route was chosen deliberately to avoid potential

geopolitical disruptions such as occurred several years ago when a pro-NATO

Ukrainian government blocked Russian gas deliveries to Western Europe to

undercut Russian attempts to come closer to western Europe.

Behind Ukraine

was the long arm of Washington. [2]

Had Ukraine joined NATO as Washington urgently sought after Kiev’s 2004

"Orange Revolution" brought Washington’s man Viktor Yushchenko in as

President, then Ukraine would have been in a strategic position to

economically strangle Russia on command. Prior to opening of Nord Stream in

November some 80% of all Russian gas exports to EU countries - mainly to

Germany, Italy and France - were flowing across Ukrainian territory.

Political instability and ongoing NATO meddling

in Ukraine dictated the decision to build the new Nord Stream undersea route

to Germany and other EU markets bypassing entirely Ukraine and Poland.

Today some 40% of all state revenue in Russia

comes from Russia’s oil and gas exports. [3]

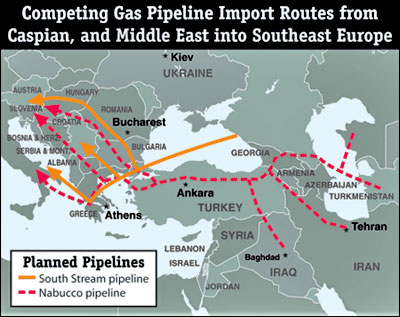

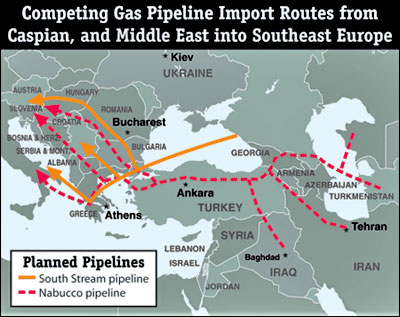

South Stream vs Nabucco

While few outside the energy industry and special political interest groups

have paid much attention to it, at the same time Nord Stream was coming into

play a ferocious geopolitical battle has also been raging over a second

planned major Gazprom Russian gas pipeline project to EU countries called

South Stream.

South Stream gas pipeline will be laid on the

Black Sea floor, pass through Bulgaria, Serbia, Hungary and Slovakia and on

to west European markets from the southern part of the EU.

To politically counter the growing Russian energy ties to the EU, with

strong Washington backing, the EU Commission proposed an alternative in 2002

called the

Nabucco pipeline, curiously named after the Verdi opera.

To date Turkey, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary and

Austria have agreed “in principle” to build the 3,900 km Nabucco pipeline

that theoretically would pump up to 31 billion cubic meters of gas annually

from the Caspian and the Middle East across Turkey into western Europe.

Nabucco partners to date include energy companies RWE of Germany; OMV of

Austria; MOL of Hungary; Botas of Turkey; Bulgaria Energy Holding of

Bulgaria; and Transgaz of Romania.

The problem is that the Nabucco partners have yet to secure gas anywhere to

fill the pipeline. Moscow has deftly locked up the gas from the obvious

supplier Azerbaijan, and surplus gas from former Soviet Republic

Turkmenistan is also secured in deals with Gazprom, leaving only Iran as an

option, something politically Washington is not ready to consider, to put it

mildly.

Both

Nord Stream and

South Stream came into being when Ukraine’s previous Yushchenko regime, with reported strong US behind-the-scenes backing, twice

disrupted transit gas flows to European markets beginning 2006. To assure

stability of supplies, Moscow created both new pipeline projects to bypass

Ukraine. [4]

The geopolitical problem for Washington and its allies in Brussels is the

fact that its Nabucco project appears dead in the water before it even gets

started. Not only has Gazprom locked up the major gas supply sources

including Azerbaijan. Nabucco is also far more costly than its Russian

rival.

Latest estimates put Nabucco’s ultimate construction cost at almost double

that of South Stream.

Tamás Fellegi, Hungarian National Development

Minister, recently stated that the cost of Nabucco gas pipeline will exceed

original plans by four times.

"No one can predict the final cost of

Nabucco, but according to optimistic estimates, its cost may reach 24-26

billion euro," Fellegi said. [5]

Former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi with Russian leaders

Medvedev (center) and Putin.

Italy’s Eni and Russian state

firm Gazprom are partners on the South Stream project.

In late October Gazprom made a major move to

secure partners for its South Stream in a Moscow meeting with its largest

consortium partner, Italy’s ENI. [6]

Some days before in September, Gazprom secured the significant participation

into South Stream of its major Nord Stream German partner, BASF Wintershall,

a major blow to Nabucco hopes.

They joined the major French energy company EDF to give the South Stream project major clout versus the floundering

Nabucco.

Last April, Turkey, also at least on paper a key player in Nabucco, gave

permission to Gazprom to begin offshore prospecting for the potential

undersea route of South Stream, a first step to gain Turkish approval to

begin construction in Turkish territorial waters on the Black Sea. Turkey is

trying to play a new role as an energy crossroads between the EU and its

neighbors.

By giving Gazprom the green light to begin

prospecting, Turkey’s Erdogan government clearly has decided not to put all

its energy eggs into the NATO Nabucco basket. [7]

Possible routes for

Gazprom’s South Stream Pipeline

Already Gazprom is the largest natural gas supplier to the EU. Gazprom with

Nord Stream and other lines plans to increase its gas supply to Europe this

year by 12% to 155 billion cubic meters.

It now controls 25% of the total European gas

market and aims to reach 30% with completion of South Stream and other

projects.

Rainer Seele, chairman of Wintershall, suggested the geopolitical thinking

behind the decision to join South Stream:

"In the global race against Asian countries

for raw materials, South Stream, like Nord Stream, will ensure access to

energy resources which are vital to our economy." [8]

But rather than Asia, the real focus of South

Stream lies to the West.

The ongoing battle between Russia’s South Stream

and the Washington-backed Nabucco is intensely geopolitical. The winner will

hold a major advantage in the future political terrain of Europe.

According to Andrei Polischuk, an energy analyst at the BKS Finance Group,

Nabucco is in far the weaker position at present.

“This project is facing several problems.

One of them is how to fill it with gas and how to find a resource basis.

The second is its growing cost. Earlier, the project was estimated at 8

billion US dollars, but at present, it has grown up to 12 to 15 billion

US dollars.” says Polischuk.

“All these projects have first and foremost

a hidden political motive. By implementing them, Europe tries to lower

its dependence on Russian gas.” [9]

Reinhard Mitschek, director of Nabucco Gas

Pipeline International, recently admitted that Nabucco now has been pushed

back until 2017, three years later than originally planned. The construction

work won’t begin until at least 2013.

He feebly admitted in a recent press conference

when pressed on a date for gas deliveries, that gas would flow,

“as soon as there are firm indications that

gas supply commitments are in place.” [10]

EU Nacht und Nebel

Raid on Gazprom

As if on cue, just days before the planned opening ceremony for Gazprom’s

Nord Stream pipeline the EU launched an unprecedented “nacht und nebel”

style raid on the offices of Gazprom and its EU partners covering ten

countries.

In response to a complaint by the Washington-friendly government of

Lithuania, on 28 September EU officials raided Gazprom and associated

offices in central and eastern European states to investigate firms involved

in the supply, transmission and storage of natural gas.

The Commission claimed the raids were linked to

“suspicions” about anti-competitive practices.

The raids were an unprecedented use of new EU “antitrust” weapons including

the threat of fines up to 10% of a company’s global turnover. Following a

Thatcherite “free market” model, the EU Commission has in recent years

forced E.ON, RWE and ENI to open up or sell their energy pipelines to

rivals.

E.ON and GDF were also forced to dismantle their market-sharing

deals.

The EU is working a so-called Third Energy Package, which imposes limits on

ownership of EU pipeline infrastructure by gas suppliers and calls for the

"unbundling" of over-concentrated ownership. Under the rules, Russia could

be forced to sell off parts of its pipeline network in the EU, something

Moscow is understandably not about to do.

It could open a Pandora’s box of geopolitical

interference with potential for anti-Russian companies to in effect sabotage

the vital and growing Russian gas trade with the EU, a mainstay today of

Russian state finances.

The Gazprom raids were explicitly political.

The EU even admits it has

little evidence:

“We’re at the beginning of the

investigation; we have our suspicions and we have to see whether these

are confirmed on the basis of the evidence we find and our analysis,"

Commission spokeswoman Amelia Torres told press in Brussels. [11]

According to Reuters,

“A Commission official, who declined to be

named, told Reuters the raids were part of the EU’s efforts to wean

itself off reliance on Russian gas and concerns about Gazprom’s power as

a state-controlled entity.”

Gazprom itself clearly links the raids to their

recent progress on South Stream:

“My guess is that it comes as Russia is

speeding up its projects, including the South Stream underwater link,” a

Gazprom source said. [12]

Vladimir Feigin, a member of the Russian

delegation discussing the issue with EU officials, charges the European

Commission with taking a "dangerous path" with the raids.

“It’s not a simple demonstration of

muscles... There are lots of issues, which are highly politicized,

including Gazprom’s long-term contracts,” he insisted. [13]

While free market game rules may sound

attractive to market outsiders, for the future planning of Gazprom long-term

fixed contracts are essential.

As oil markets reveal in recent years, while

prices sometimes fall, most often they are subject to manipulation by major

Wall Street banks like JP Morgan Chase, Citigroup or Goldman Sachs, the gang

that pushed oil prices above $147 a barrel in June 2008 at a time supply on

the world market was in glut, making a literal killing in the process.

[14]

In anticipation of the larger export market for its gas to Europe, Gazprom

has been making huge infrastructure investments across Europe which could be

wiped out by an adverse EU decision. It is in the process of doubling its

underground storage capacities for gas. It already operates gas storage

facilities in Austria and leases facilities in Britain, France and Germany

to handle the planned new flow from Nord Stream and South Stream.

As well, Gazprom has built a joint venture

storage facility with Serbia to serve gas exports to Serbia,

Bosnia-Herzegovina and Hungary.

Feasibility studies are being done for

similar joint storage projects in the Czech Republic, France, Romania,

Belgium, Britain, Slovakia, Turkey and Greece. This, in addition to the

major investment in the pipelines, makes it clear the EU raids are aimed at

Moscow’s energy jugular. [15]

Were Moscow to succeed in completing South Stream and retain its integral

control over the delivery pipeline infrastructure, it would represent

nothing less than a major geopolitical defeat for Washington.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in the

early 1990’s, Washington energy geopolitics in the Caspian region and across

Eurasia into Russia have attempted to weaken if not permanently cripple the

one major remaining geopolitical lever Moscow holds to counter Washington’s

NATO encirclement strategy. Not letting itself be totally dependent on EU

gas or oil revenues, Moscow has recently indicated it is greatly increasing

its focus on building long-term energy partnerships with its eastern

neighbors of Eurasia, most notably with China.

The geopolitical implications for Washington of

that shift will be examined in a subsequent article.

References

[1] News Wires, Russian Output Hits

Post-Soviet Highs, 2 November 2011.

[2] "Ukraine Geopolitics and the US-NATO Military Agenda”, by F. William

Engdahl, Voltaire Network, 24 March 2010.

[3] Friedbert Pflüger, "Russia and Europe: Time to bury the hatchet-and

embrace the market," 20 October, 2011, European Energy Review.

[4] RIA Novosti, "Ukraine lost reputation of reliable gas transit

country – Yanukovych," 19 October 2011.

[5] ABC.AZ, "Nabucco project cost to exceed value of South Stream and

make it world’s most expensive gas pipeline," 24 October 2011.

[6] "ENI, Gazprom CEOs discuss South Stream Development," October 17,

2011, www.offshoreenergy.com

[7] Newswires, "Turkey gives offshore permit to Gazprom for South Stream

project," 11 April, 2011.

[8] UPI, "Wintershall joins South Stream consortium," 16 September 2011.

[9] Moscow Times, "Europe still wants to go around South Stream," 30

September 2011.

[10] M K Bhadrakumar, "Russia redrawing Europe energy map," Asia Times

Online, 12 May 2011.

[11] Reuters, "EU raids Gazprom offices in anti-trust probe," 29

September 2011.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] F. William Engdahl, "More on the real reason behind high oil

prices: Part II," Global Research, 21 May 2008.

[15] M K Bhadrakumar, op. cit.