|

delivers a message on the failed coup attempt on July 15, 2016.

(Turkish government

photo)

Turkey's embattled President Erdogan suspects U.S. sympathy for the failed coup if not outright assistance to the coup plotters, a belief that has some basis in history, writes Jonathan Marshall.

The Turkish government's strong suspicion that Washington sympathized with or covertly backed the recent failed military coup - even if completely unfounded - may seriously damage the Western alliance.

After all, the preamble to the 1949 North Atlantic Treaty emphasizes the determination of the signing countries,

Emphasizing the high political stakes for the alliance, India's former Ambassador to Turkey M.K. Bhadrakumar recently declared that the,

But the assumption that NATO has always before respected peaceful political change within its ranks is false.

The historical record - which may fuel Turkish paranoia - suggests that anti-communist solidarity within the alliance has too often taken precedence over the fine democratic sentiments endorsed in NATO's founding document.

Before this summer's botched attempt, for example, Turkey previously experienced military coups in,

Comforted by the staunch anti-communism of its military, U.S. officials rarely batted an eye when Turkish officers took charge. In some cases, Washington may have had foreknowledge of the plots.

The 1960 coup was engineered by Colonel Alparslan Türkes, reportedly a liaison officer to the CIA and founder of a NATO-backed "counter-guerrilla" paramilitary organization.

After that coup, which led to mass purges of judges, prosecutors and universities, the New York Times called it,

Following the bloody 1980 coup, a story in the New York Times noted,

US-Driven Regime Change

In this article, I examine two other military interventions within the democratic heart of NATO:

Both cases offer disturbing evidence of U.S. support.

While official U.S. complicity in the two events remains unproven, even skeptical historians concede the possibility that "unofficial" agents of the U.S. government convinced coup leaders that Washington would welcome the downfall of left-leaning parliamentary parties.

Both violent episodes illustrate the dangerous impact of America's zealous pursuit of narrow ideological ends at the expense of democracy.

Greece, 1967

On April 21, 1967, in the birthplace of Western democracy, right-wing army officers seized the Greek parliament, royal palace, key communications centers and all major political leaders - a total of more than 10,000 people.

Apparently following a NATO-designed plan for military control of Greece in the event of an internal security threat, they suspended the constitution, dissolved political parties, established military courts, and set up torture centers that inflicted terrible cruelty on thousands of detainees.

NATO headquarters in Brussels, Belgium.

Despite condemnation by other European powers, the ruthless Greek junta held onto power until 1974.

It fell only after sponsoring a reckless coup against the government of Cyprus, which prompted Turkey to invade and occupy much of the island.

Many if not most Greeks, particularly those on the left, blamed Washington for the 1967 coup.

And no wonder:

The United States built military bases, brought Greece into NATO, and trained Greece's military and intelligence forces.

By 1953, U.S. ambassador to Athens John Peurifoy could boast that,

(A year later, Peurifoy would coordinate a CIA-backed coup against the democratically elected government of Guatemala.)

U.S. influence was clearly waning by 1964, however, when the left-leaning Center Union Party and its prime minister, George Papandreou, scored an electoral victory.

Papandreou resigned a year later after a dispute with the country's conservative king, but he and his fiery son Andreas were poised to win a substantial victory in the May 1967 elections.

Fearing the Left

As one senior American intelligence officer told reporter Laurence Stern,

Andreas Papandreou

The CIA proposed spending a few hundred thousand dollars on a covert program to help swing the Greek election to more conservative candidates.

Although the Agency was at that very time doing much the same thing in countries ranging from Chile to Japan, senior officials in the Johnson administration worried about security risks and rejected the plan.

Meanwhile, the CIA began hearing reports of coup plots by the king and senior military officials to block a left-wing electoral victory.

The CIA certainly had the best of sources:

Along with senior officials in Washington, the U.S. ambassador opposed a coup, writing,

But not everyone on the "country team" was a team player.

As former embassy political officer Robert Keeley observed,

A Hard-Line CIA Officer

Keeley was almost certainly referring to the Greek-American CIA officer Gust Avrakotos, who,

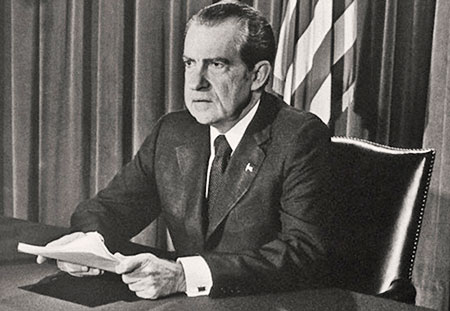

President Richard Nixon with his then-National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger in 1972.

After the colonels arrested Andreas Papandreou by threatening to put a bullet in the head of his 14-year-old son, the U.S. embassy instructed Avrakotos to tell the military to let Papandreou leave the country.

Avrakotos conveyed the message, but added:

George Crile continued,

One leading historian of the coup, while denying any official U.S. role, conceded,

Moreover, despite its official disapproval, Washington learned to live with military rule.

By 1968, the United States resumed military aid to the dictatorship, rationalizing - in the words of Defense Secretary Clark Clifford - that,

He evidently forgot to read the bit about NATO's obligation to safeguard freedom and democracy.

And after the election of President Nixon, the Pentagon stepped up secret arms shipments to Greece as relations between the White House and Athens became almost chummy.

In the fall of 1968, Nixon's vice presidential running mate, Greek-American Spiro Agnew, gave a speech lauding the junta and branding its opponents as communist tools.

A crusading Greek journalist later revealed that the KYP had secretly funneled more than half a million dollars in illegal cash to the Nixon-Agnew campaign through Thomas Pappas, a conservative Greek-American businessman and admitted CIA agent.

Another sign of the times: as the CIA station chief prepared to leave Athens in 1972, he invited nearly every member of the junta to his farewell party.

Years later, President Bill Clinton did his best to repair the damage to America's reputation among the millions of Greeks who suffered under the dictatorship.

Addressing business and community leaders in Athens in November 1999, Clinton conceded that after the military seized power in 1967,

Italy, 1970

Leaders of the Greek coup had strong fascist leanings, and zealously exported their ideology. Among their first international guests were dozens of Italian neo-fascist students and activists.

Their liaison officer was Kostas Plevris, a KYP officer and Greek neo-fascist leader.

Some of the returning Italians are suspected of joining ardent terrorists who engaged in a wave of bombings that rocked Italy throughout 1969 and into 1970, killing and wounding dozens of people.

Many of those attacks were falsely attributed to anarchists and leftists, as part of a "strategy of tension" to build political support for an authoritarian crackdown on the Left by Italy's security services.

Junio Valerio Borghese

The strategy culminated on the night of Dec. 7, 1970 with a Greek-inspired coup plot led by Prince Junio Valerio Borghese, a neo-fascist leader.

During World War II, Borghese had led an elite commando squad that murdered anti-fascist partisans for Mussolini and the Nazis. He was rescued after the war by a senior American intelligence officer who maintained close relations over the years with Borghese - even after he became honorary president of Italy's official fascist party.

In 1964 Borghese plotted with senior members of Italian military intelligence to stage a failed coup. In 1969, he took the lead in planning another coup with extreme rightists and several powerful Mafia bosses.

He also cultivated sympathizers in the military, including a number of key commanders of the armed forces and intelligence services. Most prominent among them was the head of Italy's military intelligence agency, General Vito Miceli.

Finally, on "Tora Tora" night, named after the Japanese attack code for Pearl Harbor, Borghese and his confederates assembled hundreds of militants with plans to seize weapons from the Interior Ministry's armory and descend on Rome.

Aborted Coup

At the last minute, for reasons never explained, the plot was aborted.

Borghese fled to Fascist Spain to escape justice. Italian intelligence officials dismissed the affair as a trivial incident, until prosecutors took a closer look and finally arrested General Miceli and an army general, among other participants, in 1974.

(Eventually released, Miceli became a member of parliament representing Italy's fascist party.)

General Alexander Haig, who also served as a senior White House aide under President Nixon and Secretary of State under President Reagan.

A confession by one of Borghese's top aides implicated an American engineer and CIA agent named Hugh Fenwich.

According to the aide, Fenwich had close ties to the Republican Party and called President Nixon on the evening of the coup.

He also revealed that an Italian-American businessman, Pier Francesco Talenti, had made his fleet of buses available to the coup participants. Borghese's aide claimed that Talenti was the chief intermediary between the Nixon White House and the Borghese plotters.

Significantly, just two weeks after the coup attempt, Talenti met with Deputy National Security Adviser Alexander Haig to offer a dire assessment of Italian politics.

He stirred up the White House with his warning that the situation in Italy could soon resemble that of Chile - where a Socialist had just been elected president - and that the United States must prevent the Communists from gaining power.

Talenti is something of a mystery man. He was naturalized as a U.S. citizen in 1961. He appears to have been a representative in Italy of a major American manufacturing company, Fairbanks-Morse.

He developed relations with the CIA (and the American mafia) in the early 1960s.

In the mid-1980s, he popped up in the United States, named in a major scandal implicating members of the Reagan administration, where he worked with "ethnic and minority groups."

In 1996, after losing a long series of legal battles, Talenti sued the Italian government for $5.4 billion to compensate for the loss of his properties stemming from the "trumped up charges" of his involvement in the Borghese coup plot.

Journalist Tim Weiner calls him,

There is no question that Talenti knew President Nixon personally and worked "extensively" on his 1968 presidential campaign.

He was a guest at a White House dinner in 1971. For the 1972 election, he was a regional chairman - and colleague of co-chairman Thomas Pappas - of the Finance Committee to Re-Elect the President.

Weiner also reports that Talenti engineered the appointment of Graham Martin, a hard-line conservative and former Army colonel, as Nixon's ambassador to Italy:

Seeking CIA Support

Kissinger took Talenti's warnings seriously enough in the fall of 1969 to appoint a special group within the National Security Council to,

In late 1970, Talenti weighed in again with Haig, proposing that the United States spend $8 million on a covert campaign to undercut the Left.

The administration's response, orchestrated by Ambassador Martin and the CIA station chief in Rome, was to spend millions of dollars to back leaders of the conservative Christian Democratic party, and millions more to support far-right politicians and neo-fascist activists.

Martin's covert spending totaled about $10 million. After the Borghese coup failed, Martin dismissed it as a "childish operation."

However, in a "sealed eyes only" message to Kissinger he acknowledged that,

He reported that the unnamed officers were considering,

former National Security Advisor and Secretary of State.

Martin also asked about rumors he was hearing of secret contacts between certain Italian military leaders and the White House.

Kissinger responded that his office was getting reports from "high-level" military contacts in Italy and that Talenti had informed the NSC of the military's "restiveness," but he added that,

Rather than discourage such plotting, Martin actually financed it.

In 1972, with apparent approval from both Nixon and Kissinger, he secretly paid $800,000 to General Miceli, the fascist head of Italian military intelligence and admitted colleague of the "Black Prince" Borghese.

According to a fascist member of parliament, Talenti arranged for the money to be passed in turn to the head of Italy's neo-fascist party, to pressure the Christian Democrats not to move left.

Talenti and Miceli weren't the only Italian neo-fascists with close connections to the Nixon administration.

Seven months after the Borghese coup attempt, the New York Times observed that its most "disquieting facet" was,

It quoted Luigi Turchi, a fascist deputy and member of the parliamentary defense committee, as saying his party had many supporters,

U.S. Links

The story then reported Turchi's remarkable connections to the United States:

Multiple other strands of evidence suggest that various U.S. representatives winked at anti-communist plotters in Italy during the politically volatile years of the early 1970s.

One such plotter, Count Edgardo Sogno, told in his memoirs of visiting the CIA station chief in Rome in 1974 to give advance notice of an impending coup and gauge Washington's reaction.

During a trial of right-wing extremists accused of a terrorist bombing in Milan in 1969, a former head of military counter-intelligence, General Gianadelio Maletti, suggested that U.S. intelligence agents might have provided the explosives, in order to support the "strategy of tension" in Italy.

Telling Tales

President Jimmy Carter's popular ambassador to Italy, Richard Gardner, also lent official credence to these stories in his memoir, Mission Italy:

President Richard Nixon, speaking to the nation on Aug. 8, 1974, announcing his decision to resign.

Gardner related that his predecessor, Graham Martin,

In an oral history, Gardner similarly noted that Ambassador Martin,

The stories behind U.S. involvement with right-wing military coups and plots in the heart of Western Europe should warn us that a foreign policy based on secret, anti-democratic interventions can corrupt and undermine the very allies we have pledged to defend in the name of democracy.

This history has also left a long-lasting stain on America's credibility as a champion of 'freedom'.

The United States may well pay a heavy political price if our dark history fuels Turkish claims of Washington's complicity in this summer's failed military coup.

|