|

by Matt Hackett

March 21, 2016

from

Medium Website

A capitalist

society requires a culture based on images.

It needs to furnish

vast amounts of entertainment in order to stimulate

buying and anesthetize the injuries of class, race, and

sex. And it needs to gather unlimited amounts of

information, the better to exploit natural resources,

increase productivity, keep order, make war, give jobs

to bureaucrats.

The camera's twin

capacities, to subjectivize reality and to objectify it,

ideally serve these needs and strengthen them.

Cameras define

reality in the two ways essential to the workings of an

advanced industrial society: as a spectacle (for masses)

and as an object of surveillance (for rulers).

Susan Sontag

"The

Image-World" (1973)

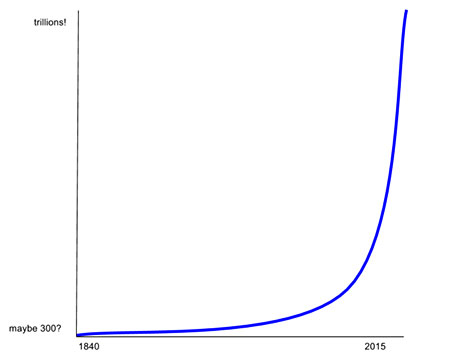

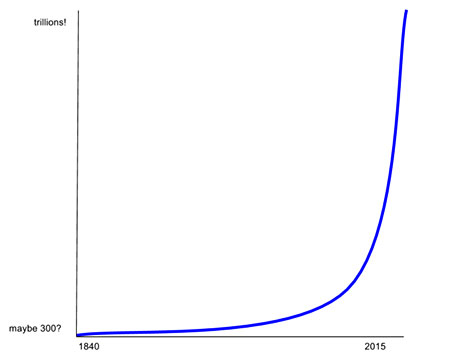

More photographs have been taken

in the past year than were taken on all film

combined.

More than 2 trillion photos were shared

last year, perhaps twice or more were captured and sit dormant on

phone hard drives. This says nothing of video.

Sontag wrote the above from the gentle upward slope of the

exponential curve of image-creation. She could probably feel the

slight breeze of acceleration, but her face would melt at the

velocity images have attained in the decade since her death.

The history of images

in one specious graph

Humanity's appetite for creating, sharing, and consuming images

appears insatiable.

To do some back-of-the-envelope math:

(Images perceptible per second) ×

(Waking seconds per day) × (Human population) = 10 × 57,600 ×

7,400,000,000 = 4.3 quadrillion

The upper limit on global image

consumption is 4.2 quadrillion per day, or 1.6 quintillion images a

year, give or take.

Facebook,

Google, and Twitter's ruthless

pursuit of dominance in video needs no further explanation.

Before images,

there was time

Humanity's appetite for time grew on a similarly aggressive curve.

Before the industrial revolution, it was uncommon for clocks to have

minute hands. Only a very select class could afford a private

timepiece until the 20th century.

Until the 1840s,

time was local and highly variable.

Each town set its own clock, from which private clocks would be

roughly set by hand. The time in Pittsburg might be 27 minutes

earlier than that in New York and no one much cared.

The railways made it possible to cross between these esoteric times

much more frequently than by horse or foot, and demand for time

expanded.

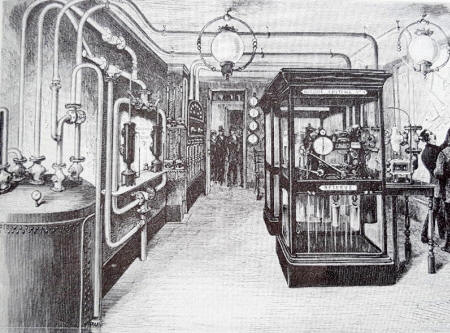

Initially, time was an industrial

substrate:

running efficient trains required

coordinated, well-publicized time across long distances.

The market for time exploded alongside

the growth of rail, and by the 1870s time was a hot luxury item.

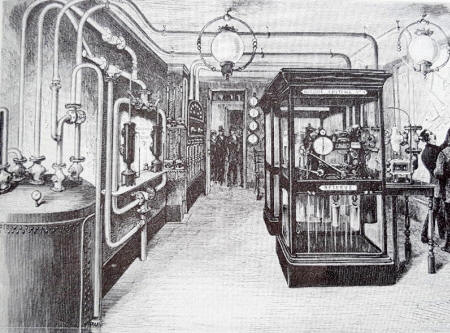

In Paris, private residences, factories,

and watchmakers' shops could buy time:

a special clock outfitted with a

pneumatic synchronization mechanism was installed on the

premises and linked by underground tube to a central time pump

that dispensed time in the form of puffs of air.

Any ambitious gentleman subscribed to

this service, paying handsomely for time.

"Pneumatic Unification of Time: The Control Room"

circa 1880 from

Compagnie Générale des Horloges Pneumatiques,

Archives de la Ville

de Paris via Peter Galison's book

Einstein's Clocks,

Poincaré's Maps: Empires of Time

In the early 20th century, time became a

commodity.

World War I saw the introduction of

wristwatches to servicemen for coordinating trench warfare. The

digital computer and eventually the Internet required time on an

even more extreme scale. Without ubiquitous, precise (and to a

lesser degree accurate) time, none of the software protocols

involved in delivering this article to your screen would be

possible.

These days,

time is so common it is invisible.

Within reach of me right now are at

least ten milliseconds-precise clocks (iPhone, Android, Kindle,

stereo, desktop, laptop, oven, TV, cable box, digital watch), most

of which are kept accurate by syncing continuously, wirelessly, with

an atomic clock.

Still, our time-appetite is never sated:

Stock traders are

working hard against physical

barriers to coordinate their process below the millisecond.

Like images, a capitalist society

requires time.

In the 19th century, this ubiquity of time was far

beyond the realm of fiction. Time seems to us a true fact of the

world only because we have been steeped in so much of it for so

long.

The exponential expansion of time snuck

up on us.

Creating even

more images

By 2020, 80% of the world will be in possession of a physically

unlimited camera attached (mostly)

to an instantaneous global image distribution network.

This will also be the screen that allows

access the visual experience of the rest of the world.

Smartphones still require a complex series of time-consuming

gestures to create and distribute an image. An exponentially

increasing appetite for images, as a practical matter, requires

exponentially increasing creation. Wearable cameras will take care

of that.

Wearable image-creation technology is here today. An Alibaba search

turns up dozens of Shenzhen

manufacturers able to produce 1080p, Wi-Fi-enabled cameras from

commodity components for less than $50.

I have a few of these on my desk -

they're not polished, but were Apple (or Xiaomi) to take up the

project, a workable design and price point is easy to imagine.

Self-portrait as Glasshole

(Someday this will

read as kitschy fun,

not

reputation-destroying)

Google Glass was an abject failure

as a consumer device.

This may seem strange, the wearable

camera being by far its most well-implemented feature.

Glass failed because it was a tool for creating an order of

magnitude more images before they were ready to be consumed.

Skeptics rightly

asked,

"Are you taking a video of me right

now?" because there was no conceivable place to view such

images.

Our appetite hadn't grown large enough,

nor had the software to cater to it.

Beme, Snapchat, Facebook, and likely

dozens of others are building that consumption software right now.

(Technology for consuming images has always lagged behind technology

for creating them. Color television format wars spanned a decade,

and even that during a period when TV shows were still finding their

footing beyond imitating vaudeville.)

Infinite

vision

What happens when images are integrated as fully into our reality

as time?

We are approaching a world in which visual and auditory presence at

a distance - seeing as another, instantly - is not a rare luxury

good, but a basic assumption of society and industry.

The superpower of unbounded remote

vision is becoming mundane.

Nothing, of course, is inevitable. We could rein in our image

appetite before wearable cameras become necessary. But there are

just as many possibilities for human flourishing as there are for

malice in an infinite-image world. (We will see plenty of both.)

Susan Sontag's image-world is dark and instrumental:

images are class succor and control.

Logical enough from the perspective of

1970s photography, in which camera ownership and image distribution

were limited to the relatively powerful.

The era we are in the midst of, with a

profusion of cheap, miniature, wearable, networked cameras and

screens, is quite different.

As they become ubiquitous, I doubt we will think of these things as

cameras much longer. We hardly think of the tiny quartz wafers

inside every integrated circuit as "clocks," if we think of them at

all.

Cameras will become equally invisible

facilitators of remote vision.

The ubiquity of time makes stamping it with a moral judgment absurd.

We don't fear or reject

time, it is simply part of what is

admirable about our reality (instant navigation,

the Internet), and also part of

what is less so (irrational obsession over productivity, nuclear

warfare).

We have already become clocks. We will soon become cameras.

What we do with that power is up to

us...

|