|

found Google privacy violations that the FTC missed.

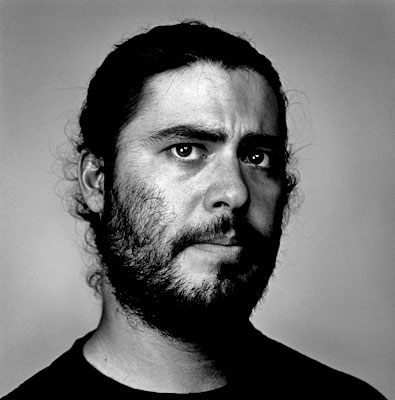

Photo: Peter McCollough/Wired

How a Lone Grad Student Scooped the Government and What It Means for Your Online Privacy

If Mayer’s instinct was right, advertisers were eying people as they moved from one website to another even though their browsers were configured to prevent this sort of digital shadowing. Working long hours at his office, Mayer ran a series of clever tests in which he purchased ads that acted as sniffers for the sort of unauthorized cookies he was looking for.

He hit the jackpot, unearthing one of the biggest privacy scandals of the past year:

The feds are often the last to know about

digital invasions of your privacy.

But the FTC didn’t discover the violation. Mayer

is a 25-year-old grad student working on law and computer science degrees at

Stanford University. He shoehorned his sleuthing between classes and

homework, working from an office he shares in the Gates Computer Science

Building with students from New Zealand and Hong Kong. He doesn’t get paid

for his work and he doesn’t get much rest.

A privacy official in Germany forced Google to hand over the hard drives of cars equipped with 360-degree digital cameras that were taking pictures for its Street View program. The Germans discovered that Google wasn’t just shooting photos: The cars downloaded a panoply of sensitive data, including emails and passwords, from open Wi-Fi networks.

Google had secretly done the same in the United

States, but the FTC, as well as the Federal Communications Commission, which

oversees broadcast issues, had no idea until the Germans figured it out.

But data mining, which has become central to the corporate bottom line, can be downright creepy, with companies knowing what you search for, what you buy, which websites you visit, how long you browse - and more. Earlier this year, it was revealed that Target realized a teenage customer was pregnant before her father knew; the firm identifies first-term pregnancies through, among other things, purchases of scent-free products.

It’s akin to someone rifling through your

wallet, closet or medicine cabinet, but in the digital sphere no one picks

your pocket or breaks into your house. The tracking is done mostly without

your knowledge and, in many cases, despite your attempts to stop it, as

Mayer discovered.

But the agency’s ambitions are clipped by a lack of both funding and legal authority, reflecting a broader uncertainty about the role government should play in what is arguably America’s most promising new industry.

Companies like Facebook and Google are global brands for which data mining is at the core of present and future profits. How far should they go? Current laws provide few limits, mainly banning data collection from children under 13 and prohibiting the sale of personal medical data. Beyond that, it’s a digital mosh pit, and it’s likely to remain that way because more regulation tends to be regarded by politicians in both parties as meaning fewer jobs.

Students will probably continue to beat the FTC to the punch: The agency has just one privacy technologist working in its Division of Privacy and Identity Protection and one in the Division of Financial Practices.

This isn’t the usual sort of story about regulation watered down by intimate ties between government officials and the industry they oversee.

Unlike the U.S. Minerals Management Service, where not long ago a number of officials were found to have shared drugs and had sex with representatives of the oil and gas industry, key FTC officials hired by the Obama administration are privacy hawks who worked previously for consumer-rights groups like Public Citizen and the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Under Chairman Jon Liebowitz, a Democrat appointed to the FTC in 2004 and tapped as chairman by President Obama in 2009, the FTC has pushed boundaries; its first privacy technologist, hired shortly after Liebowitz became chairman, was a semifamous activist who made a name for himself by printing fake boarding passes to draw attention to airline security lapses (the FBI, which raided his house, was not pleased).

The agency is working with the tech industry to

create and voluntarily adopt a Do Not Track option, so that consumers can

avoid some intrusive web tracking by advertising firms. And it

issued a report this year that called for

new legislation to define what data miners can and cannot do.

While Mayer has an ultrafast internet connection, top-of-the-line computer, an office chair he loves and tasty lunches for free (“Stanford students do not want in any way,” he notes), the FTC technologist uses his personal laptop and, because there is no Wi-Fi at the agency, connects to the internet by tethering it to his iPhone.

He browses the web at cellphone speed. There are

no free lunches.

Christopher Soghoian, the security gadfly, worked with the FTC until 2010.

Photo: Graeme Mitchell The FTC is headquartered in a landmarked building on Pennsylvania Avenue flanked by two sculptures of a man trying to restrain a muscle-bound horse that is straining to gallop away.

The sculptures, completed in 1942, are entitled “Man Controlling Trade,” and they explain a lot about the FTC’s current dilemma. The notion of controlling trade, popular when the sculptures were erected a half-century ago, is not a vote-winner today.

The FTC was an early battleground of the

movement that began in the Reagan era to reduce government regulation. The

agency had more than 1,700 employees in the 1970s, but is down to 1,176

today, even though the economy has more than doubled in that span. The FTC’s

responsibilities are quite vast: It must police everything from financial

scams to antitrust activity, identity theft and misleading advertising.

California Rep. Mary Bono-Mack, at a recent hearing on privacy legislation, warned that the government,

Although the American Civil Liberties Union may see an epidemic of privacy violations, Bono-Mack said,

The skepticism is not just an outside-the-building phenomenon; it comes from within the FTC, too.

One of the agency’s five commissioners, Republican Thomas Rosch, dissented from its 2013 budget request, which asks for less money than the prior year budget of $312 million.

Rosch said he believed the FTC still wanted too much.

The cold shoulder is not entirely Republican.

Earlier this year the Obama administration unveiled a “Privacy Bill of Rights” that sets a variety of enviable standards for consumer privacy.

The document, which among other things would allow individuals to control the data collected on them, was welcomed by consumer groups.

But it’s not legislation. It’s a wish-list. The

administration hopes that some of its wishes, like a Do Not Track option,

will be granted through voluntary industry standards. But many of the wishes

require Congress to pass laws that it is unlikely to pass anytime soon. The

FTC’s meager budget request would seem to be the best indication yet of the

prospects for significantly greater federal privacy protection.

But Sen. John McCain, R-Arizona, was counseled

in his presidential bid by both Carly Fiorina, the former CEO of

Hewlett-Packard, and by Meg Whitman, the former CEO of eBay who now heads

HP. Silicon Valley is one of the country’s few global growth industries;

politicians are reluctant to put restrictions on what it can and cannot do.

A year later, in 2010, the FTC hired its first chief technologist, Edward Felten, a Princeton computer scientist who is highly regarded in tech policy circles.

But the three men who have filled the privacy technologist job that Soghoian filled first (each have served for about a year) faced an awkward problem: The desktop in their office is digitally shackled by security filters that make it impossible to freely browse the Web.

Crucial websites are off-limits, due to concerns

of computer viruses infecting the FTC’s network, and there are severe

restrictions on software downloads. When Soghoian tried to download a

Wi-Fi-sniffing app, his boss told him within a few minutes that he had

tripped a security alarm; he could not use the app on his computer. It had

to be deleted immediately.

A handful of unfiltered computers are available

in restricted labs at the FTC’s headquarters on Pennsylvania Avenue and its

satellite offices on New Jersey Avenue and M Street, but this is an ungainly

setup. Rather than leaving their office, waiting for an elevator, swiping

their ID badges across a sensor at the lab’s locked door and logging into a

computer soaked with malware (because lab PCs are used to test suspicious

applications), the technologists have instead stayed in their office and

tethered their personal laptops to their personal cellphones.

Each time - Soghoian in 2010, Brennan in 2011 - they got tantalizingly close, with new machines delivered to them. But the computers were never connected to the internet.

Someone at the agency - they don’t know who - got cold feet.

Only one FTC official has an unfiltered desktop: Felten, the chief technologist.

He is the sort of unconventional public servant the FTC has hired in recent years. He was an expert witness in the landmark antitrust suit against Microsoft, a board member of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and in April he participated in a privacy hackathon with his teenage daughter. Felten, hired mainly to provide policy advice to the FTC chairman, also conducts investigations of suspicious websites or apps - this is what he uses the unshackled computer for.

During an interview, he pointed to it, a bit like a museum guide gesturing toward a priceless artwork, and said,

Felten, who plans to resume full-time teaching at Princeton in the fall, was asked whether he has better technological resources there.

The Federal Trade Commission building in Washington, D.C.

Photo: Wikimedia The mismatch between FTC aspirations and abilities is exemplified by its Mobile Technology Unit, created earlier this year to oversee the exploding mobile phone sector.

The six-person unit consists of a paralegal, a program specialist, two attorneys, a technologist and its director, Patricia Poss.

For the FTC, the unit represents an important allocation of resources to protect the privacy rights of more than 100 million smartphone owners in America. For Silicon Valley, a six-person team is barely a garage startup.

Earlier this year, the unit issued a highly publicized report on mobile apps for kids; its conclusion was reflected in the subtitle, “Current Privacy Disclosures Are Disappointing.”

It was a thin report, however. Rather than actually checking the personal data accessed by the report’s sampling of 400 apps, the report just looked at whether the apps disclose, on the sites where they are sold, the types of personal data that would be accessed and what the data would be used for. The body of the report is just 17 pages.

The FTC says it will do deeper research in future reports.

Poss, the unit’s director, has one. The Blackberry dominated when Al Gore ran for president, but today it’s barely an also-ran with just 12 percent of the smartphone market. That’s not a problem if you only use your Blackberry for texts, emails and calls.

But it’s a problem if, like Poss, your job is to

keep track of what’s happening in the smartphone market. Most consumers use

Androids or iPhones, and most of the apps written for them are not available

on the Blackberry.

She has an iPhone as well as an Android.

FTC officials are reluctant to talk about their lack of funding, partly because public whining, especially during hard economic times, is infrequently rewarded.

It’s also politically unwise. A vocal portion of

the electorate believes the government and its regulatory arms have too much

money and power as it is. Additionally, the FTC is trying to keep the tech

industry honest by hinting that the feds are watching everything. It does

not help if Silicon Valley realizes the FTC possesses just a handful of

iPhones and Androids that are kept under lock and key in the basement.

Poss, a lawyer who has worked at the FTC for more than 12 years, began to look uncomfortable, as though she was in the witness box, unsure what she was supposed to say.

She made amends by noting she can use her office computer to look at the smartphone app descriptions posted on the websites where they are sold.

Then she reversed herself.

She hesitantly mentioned that Apple’s app store

is among the sites blocked by the FTC’s security system. If she wants to

look at the most popular websites for mobile apps, she has to go to a

basement lab.

David Vladeck, Director of the FTC’s Bureau of Consumer Protection, maintains an aura of secrecy around the commission’s testing labs.

Photo: AP/Alex Brandon The FTC maintains an aura of secrecy about its testing labs in Washington.

Their location is known but not much else. Officials would not talk about the equipment in the labs. Poss and Farrell refused to divulge the number of iPhones and Androids, though it appears to be not much more than a handful.

It is hard for outsiders to know more because the FTC refuses to let reporters visit the labs.

The embedding program during the Iraq war gave

reporters the chance to report on the planning and execution of secret

military operations. The FTC’s labs would not seem to rival the technology

displayed when journalists ride aboard nuclear-powered submarines, for

instance.

Current and former FTC officials say the labs are the size of suburban living rooms, with computers and accessories that do not look much different from what would be seen at a Kinko’s.

Vladeck’s appointment, in 2009, was welcomed by consumer-rights activists because of the nearly three decades he worked as a crusading lawyer for Public Citizen, which was founded by Ralph Nader; Vladeck has advocated long and hard for better government regulation.

A conversation with Vladeck, who has argued four cases before the U.S. Supreme Court and won three of them, is akin to a combative courtroom session. He often leans across the table and speaks in a high-pitched bellow.

During an interview in his office, he said that when he arrived at the FTC,

That’s partly because the Bush-era FTC was not terribly aggressive on privacy but also because data mining has particularly taken off in the past few years.

Since he arrived, the FTC has reached privacy settlements with the some of the largest tech firms, including Facebook, Google and Twitter, though in each case, there were no fines, because the FTC’s authority to issue fines on a first offense is limited.

The agency is like a runner with two sprained

ankles, because in addition to its narrow legal power, it has a surprisingly

small staff to pursue its legal cases.

There are about 20 lawyers working on privacy cases at the FTC.

And the FTC has another problem: Republican Rep.

John Mica, chairman of the House Committee on Transportation and

Infrastructure, is

trying to evict the agency from its

headquarters, which is on a prime block of Pennsylvania Avenue.

Yet those cases demonstrated something else, too - the FTC’s limited power.

The agency was created in 1914 to prevent unfair and deceptive practices in commerce. Unfairness is harder to prove in privacy - what’s inappropriate data collection to one person might be fair and harmless to another - so the FTC is focusing enforcement efforts on deception. That means a company has to say one thing about its data-collection practices and do another.

But many companies have privacy policies that

say very little - in which case, they aren’t deceiving consumers if they do

things that might be untoward.

Companies that follow these strategies - and

many do - are difficult targets for the FTC.

The agency can take companies to court, but its overworked lawyers don’t really have the time to go the distance against the bottomless legal staffs in Silicon Valley.

The FTC

settled the Buzz case with Google, which

agreed to annual privacy audits for 20 years and promised to not lie to

consumers about what the company does with their data. If Google violates

the settlement, it then faces financial penalties that could be quite large

- this is akin to a two-strike rule.

The investigation was opened in 2009, when MySpace was already a fading giant; by the time it was concluded in May, MySpace was all but a museum artifact.

On Twitter, reaction to the suit included jokes to the effect of,

Although the agency has some sway with Google and other companies that are sensitive to reputational issues - an FTC settlement might not hurt Google’s bottom line but the bad press could - it has less influence over data mining firms like Lexis Nexis, Choicepoint and RapLeaf, whose revenues come mostly from businesses rather than consumers.

This is a major hole in the government’s effort to protect consumers from privacy violations, and the FTC has all but thrown up its hands in futility. The privacy report it issued earlier this year called on Congress to pass legislation that would set guidelines on acceptable practices by data miners.

The odds of that happening are quite long,

because of industry opposition to government oversight and the difficulty of

getting agreement in Congress on what should and should not be allowed. U.S. officials took Google’s word that its Street View cars weren’t sniffing open Wi-Fi networks. The German government dug deeper.

Photo: Sign Language/Flickr Even though he lives in university housing [TD5], Jonathan Mayer is a star in the world of digital privacy; he is the mop-haired kid who busted Google in his spare time.

Silicon Valley companies seek him out to learn what he’s up to. Mayer, being clever, uses these encounters to learn about the companies. What are they thinking about the most? What do they fear the most?

He has made another discovery.

Google promised its cars were only taking

pictures, and the firm’s word was enough for U.S. officials.

It’s the globalization of digital regulation:

What happens in one country can affect all countries.

Facebook’s international headquarters are located in Dublin, so the firm had to comply. Last year it gave Schrems more than 1,200 pages of data that included just about every keystroke he had made while on the social network, including items he had deleted and location information he had never provided.

Facebook had kept almost every poke and like,

every friend and defriend, every invitation accepted or rejected. Schrems

posted the information online and compared his Facebook dossier to the data

that the East German secret police, the Stasi, had kept on millions of

citizens.

The company acknowledged that the change was the

result of a harsh report issued by Irish authorities looking into the

Schrems case. Ireland wasn’t trying to protect the privacy rights of

Americans, but its pressure on Facebook had precisely that effect.

In short order, the search giants complied - not only for their European customers but for Americans, too.

The power of Europe’s privacy regulators - and the weakness of America’s - was demonstrated most vividly in the Street View dustup.

While there was only modest protest against Google photographing American streets and homes, the company immediately ran into big trouble when its cars began to roam around Europe. The collection and abuse of personal information was a hallmark of not only the Nazi regime and its allies during the World War II era, but of the communist regimes that ruled Eastern Europe during the Cold War.

Throughout Europe, local and national

authorities expressed concerns about Street View, and the project quickly

hit a number of walls.

Google downplayed the revelation by contending

the downloads were innocuous - just technical data, not personal

information.

Caspar insisted the company hand over a hard

drive. After a few months, Google complied. Caspar discovered that Google

had downloaded vast amounts of personal data.

He leaned forward, speaking a bit more slowly.

He argued that although the Germans uncovered Street View’s data collection, the FTC was not asleep at the wheel because it was investigating Street View at the time.

But Vladeck said the FTC could not have done much even if it had examined a hard drive, since the agency’s reach extends only to unfair or deceptive practices. Google had never told consumers it wasn’t downloading Wi-Fi data, so it hadn’t deceived them by doing so.

To prove an unfair practice, the FTC would have needed to show that the data downloads caused consumers an unavoidable harm.

The agency quietly closed its investigation in

late 2010 with no action.

The FCC sharply criticized Google in April but fined the company just $25,000, which is not even a rounding error in the web giant’s first quarter profit of $2.89 billion.

|