by Seymour M. Hersh

March 5, 2007

from

TheNewYorker Website

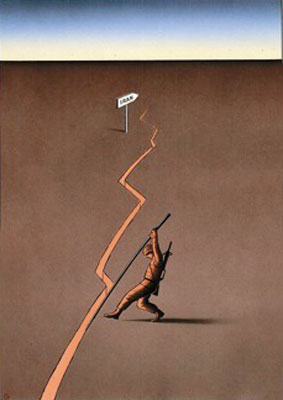

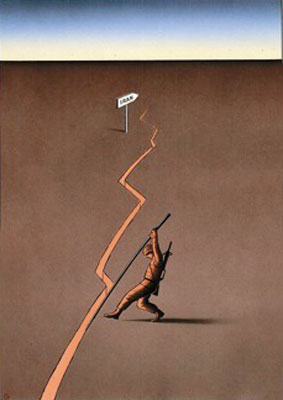

Efforts to curb Iran's

influence

have involved the United States in worsening Sunni-Shiite

tensions.

A STRATEGIC SHIFT

In the past few months, as the situation in Iraq has deteriorated,

the Bush

Administration, in both its public diplomacy and its covert operations, has

significantly shifted its Middle East strategy.

The "redirection," as some inside the White

House have called the new strategy, has brought the United States closer to

an open confrontation with Iran and, in parts of the region, propelled it

into a widening sectarian conflict between Shiite and Sunni Muslims.

To undermine Iran, which is predominantly Shiite, the Bush Administration

has decided, in effect, to reconfigure its priorities in the Middle East. In

Lebanon, the Administration has cooperated with Saudi Arabia's government,

which is Sunni, in clandestine operations that are intended to weaken

Hezbollah, the Shiite organization that is backed by Iran.

The U.S. has also taken part in clandestine

operations aimed at Iran and its ally Syria. A by-product of these

activities has been the bolstering of Sunni extremist groups that espouse a

militant vision of Islam and are hostile to America and sympathetic to Al

Qaeda.

One contradictory aspect of the new strategy is that, in Iraq, most of the

insurgent violence directed at the American military has come from Sunni

forces, and not from Shiites. But, from the Administration's perspective,

the most profound - and unintended - strategic consequence of the Iraq war

is the empowerment of Iran.

Its President, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, has made

defiant pronouncements about the destruction of Israel and his country's

right to pursue its nuclear program, and last week its supreme religious

leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, said on state television that,

"realities in the region show

that the arrogant front, headed by the U.S. and its allies, will be the

principal loser in the region."

After the revolution of 1979 brought a religious

government to power, the United States broke with Iran and cultivated closer

relations with the leaders of Sunni Arab states such as Jordan, Egypt, and

Saudi Arabia.

That calculation became more complex after the

September 11th attacks, especially with regard to the Saudis. Al

Qaeda is Sunni, and many of its operatives came from extremist religious

circles inside Saudi Arabia. Before the invasion of Iraq, in 2003,

Administration officials, influenced by neoconservative ideologues, assumed

that a Shiite government there could provide a pro-American balance to Sunni

extremists, since Iraq's Shiite majority had been oppressed under Saddam

Hussein.

They ignored warnings from the intelligence

community about the ties between Iraqi Shiite leaders and Iran, where some

had lived in exile for years. Now, to the distress of the White House, Iran

has forged a close relationship with the Shiite-dominated government of

Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki.

The new American policy, in its broad outlines, has been discussed publicly.

In testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in January,

Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice said that there is,

"a new strategic alignment in the Middle

East," separating "reformers" and "extremists"; she pointed to the Sunni

states as centers of moderation, and said that Iran, Syria, and

Hezbollah were "on the other side of that divide." (Syria's Sunni

majority is dominated by the Alawi sect.)

Iran and Syria, she said,

"have made their choice and

their choice is to destabilize."

Some of the core tactics of the redirection are

not public, however.

The clandestine operations have been kept secret, in

some cases, by leaving the execution or the funding to the Saudis, or by

finding other ways to work around the normal congressional appropriations

process, current and former officials close to the Administration said.

A senior member of the House Appropriations Committee told me that he had

heard about the new strategy, but felt that he and his colleagues had not

been adequately briefed. "We haven't got any of this," he said. "We ask for

anything going on, and they say there's nothing. And when we ask specific

questions they say, 'We're going to get back to you.' It's so frustrating."

The key players behind the redirection are,

-

Vice-President Dick Cheney

-

the

deputy national-security adviser Elliott Abrams

-

the departing Ambassador to Iraq (and

nominee for United Nations Ambassador) Zalmay Khalilzad

-

Prince Bandar bin Sultan, the Saudi national-security adviser

While Rice

has been deeply involved in shaping the public policy, former and current

officials said that the clandestine side has been guided by Cheney.

(Cheney's office and the White House declined to comment for this story; the

Pentagon did not respond to specific queries but said, "The United States is

not planning to go to war with Iran.")

The policy shift has brought Saudi Arabia and Israel into a new strategic

embrace, largely because both countries see Iran as an existential threat.

They have been involved in direct talks, and the Saudis, who believe that

greater stability in Israel and Palestine will give Iran less leverage in

the region, have become more involved in Arab-Israeli negotiations.

The new strategy "is a major shift in American policy - it's a sea change,"

a U.S. government consultant with close ties to Israel said.

The Sunni states,

"were petrified of a Shiite resurgence, and

there was growing resentment with our gambling on the moderate Shiites

in Iraq," he said. "We cannot reverse the Shiite gain in Iraq, but we

can contain it."

"It seems there has been a

debate inside the government over what's the biggest danger - Iran or

Sunni radicals," Vali Nasr, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, who has

written widely on Shiites, Iran, and Iraq, told me.

"The Saudis and some in the

Administration have been arguing that the biggest threat is Iran and the

Sunni radicals are the lesser enemies. This is a victory for the Saudi

line."

Martin Indyk, a senior State Department official

in the Clinton Administration who also served as Ambassador to Israel, said

that,

"the Middle East is heading

into a serious Sunni-Shiite Cold War."

Indyk, who is the director of the Saban Center

for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institution, added that, in his

opinion, it was not clear whether the White House was fully aware of the

strategic implications of its new policy.

"The White House is not just doubling the

bet in Iraq," he said. "It's doubling the bet across the region. This

could get very complicated. Everything is upside down."

The Administration's new policy for containing

Iran seems to complicate its strategy for winning the war in Iraq.

Patrick Clawson, an expert on Iran and the

deputy director for research at the Washington Institute for Near East

Policy, argued, however, that closer ties between the United States and

moderate or even radical Sunnis could put "fear" into the government of

Prime Minister Maliki and "make him worry that the Sunnis could actually

win" the civil war there.

Clawson said that this might give Maliki an

incentive to cooperate with the United States in suppressing radical Shiite

militias, such as Moqtada al-Sadr's Mahdi Army.

Even so, for the moment, the U.S. remains dependent on the cooperation of

Iraqi Shiite leaders. The Mahdi Army may be openly hostile to American

interests, but other Shiite militias are counted as U.S. allies. Both

Moqtada al-Sadr and the White House back Maliki.

A memorandum written late last year by Stephen

Hadley, the national-security adviser, suggested that the Administration try

to separate Maliki from his more radical Shiite allies by building his base

among moderate Sunnis and Kurds, but so far the trends have been in the

opposite direction.

As the Iraqi Army continues to founder in its

confrontations with insurgents, the power of the Shiite militias has

steadily increased.

Flynt Leverett, a former Bush Administration National Security Council

official, told me that "there is nothing coincidental or ironic" about the

new strategy with regard to Iraq.

"The Administration is trying

to make a case that Iran is more dangerous and more provocative than the

Sunni insurgents to American interests in Iraq, when - if you look at

the actual casualty numbers - the punishment inflicted on America by the

Sunnis is greater by an order of magnitude," Leverett said.

"This is all part of the

campaign of provocative steps to increase the pressure on Iran. The idea

is that at some point the Iranians will respond and then the

Administration will have an open door to strike at them."

President George W. Bush, in a speech on January

10th, partially spelled out this approach.

"These two regimes" - Iran and Syria -

"are

allowing terrorists and insurgents to use their territory to move in and

out of Iraq," Bush said.

"Iran is providing material

support for attacks on American troops. We will disrupt the attacks on

our forces. We'll interrupt the flow of support from Iran and Syria. And

we will seek out and destroy the networks providing advanced weaponry

and training to our enemies in Iraq."

In the following weeks, there was a wave of

allegations from the Administration about Iranian involvement in the Iraq

war.

On February 11th, reporters were

shown sophisticated explosive devices, captured in Iraq, that the

Administration claimed had come from Iran. The Administration's message was,

in essence, that the bleak situation in Iraq was the result not of its own

failures of planning and execution but of Iran's interference.

The U.S. military also has arrested and interrogated hundreds of Iranians in

Iraq.

"The word went out last August for the

military to snatch as many Iranians in Iraq as they can," a former

senior intelligence official said.

"They had five hundred locked

up at one time. We're working these guys and getting information from

them. The White House goal is to build a case that the Iranians have

been fomenting the insurgency and they've been doing it all along - that

Iran is, in fact, supporting the killing of Americans."

The Pentagon consultant confirmed that hundreds

of Iranians have been captured by American forces in recent months.

But he told me that that total includes many

Iranian humanitarian and aid workers who "get scooped up and released in a

short time," after they have been interrogated.

"We are not planning for a war with Iran,"

Robert Gates, the new Defense Secretary, announced on February 2nd,

and yet the atmosphere of confrontation has deepened.

According to current and former American

intelligence and military officials, secret operations in Lebanon have been

accompanied by clandestine operations targeting Iran.

American military and special-operations teams

have escalated their activities in Iran to gather intelligence and,

according to a Pentagon consultant on terrorism and the former senior

intelligence official, have also crossed the border in pursuit of Iranian

operatives from Iraq.

At Rice's Senate appearance in January, Democratic Senator Joseph Biden, of

Delaware, pointedly asked her whether the U.S. planned to cross the Iranian

or the Syrian border in the course of a pursuit.

"Obviously, the President isn't going to

rule anything out to protect our troops, but the plan is to take down

these networks in Iraq," Rice said, adding, "I do think that everyone

will understand that - the American people and I assume the Congress

expect the President to do what is necessary to protect our forces."

The ambiguity of Rice's reply prompted a

response from Nebraska Senator Chuck Hagel, a Republican, who has been

critical of the Administration:

Some of us remember 1970, Madam Secretary.

And that was Cambodia. And when our government lied to the American

people and said,

"We didn't cross the border going into

Cambodia," in fact we did.

I happen to know something about that, as do

some on this committee. So, Madam Secretary, when you set in motion the

kind of policy that the President is talking about here, it's very, very

dangerous.

The Administration's concern about Iran's role

in Iraq is coupled with its long-standing alarm over Iran's nuclear program.

On Fox News on January 14th, Cheney warned of

the possibility, in a few years,

"of a nuclear-armed Iran,

astride the world's supply of oil, able to affect adversely the global

economy, prepared to use terrorist organizations and/or their nuclear

weapons to threaten their neighbors and others around the world."

He also said,

"If you go and talk with the

Gulf states or if you talk with the Saudis or if you talk with the

Israelis or the Jordanians, the entire region is worried... The threat

Iran represents is growing."

The Administration is now examining a wave of

new intelligence on Iran's weapons programs.

Current and former American officials told me

that the intelligence, which came from Israeli agents operating in Iran,

includes a claim that Iran has developed a three-stage solid-fuelled

intercontinental missile capable of delivering several small warheads - each

with limited accuracy - inside Europe.

The validity of this human intelligence is still

being debated.

A similar argument about an imminent threat posed by weapons of mass

destruction - and questions about the intelligence used to make that case -

formed the prelude to the invasion of Iraq.

Many in Congress have greeted the claims about

Iran with wariness; in the Senate on February 14th, Hillary

Clinton said,

"We have all learned lessons

from the conflict in Iraq, and we have to apply those lessons to any

allegations that are being raised about Iran. Because, Mr. President,

what we are hearing has too familiar a ring and we must be on guard that

we never again make decisions on the basis of intelligence that turns

out to be faulty."

Still, the Pentagon is continuing intensive

planning for a possible bombing attack on Iran, a process that began last

year, at the direction of the President.

In recent months, the former intelligence

official told me, a special planning group has been established in the

offices of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, charged with creating a contingency

bombing plan for Iran that can be implemented, upon orders from the

President, within twenty-four hours.

In the past month, I was told by an Air Force adviser on targeting and the

Pentagon consultant on terrorism, the Iran planning group has been handed a

new assignment: to identify targets in Iran that may be involved in

supplying or aiding militants in Iraq. Previously, the focus had been on the

destruction of Iran's nuclear facilities and possible regime change.

Two carrier strike groups - the Eisenhower and the Stennis - are now in the

Arabian Sea. One plan is for them to be relieved early in the spring, but

there is worry within the military that they may be ordered to stay in the

area after the new carriers arrive, according to several sources.

(Among other concerns, war games have shown that

the carriers could be vulnerable to swarming tactics involving large numbers

of small boats, a technique that the Iranians have practiced in the past;

carriers have limited maneuverability in the narrow Strait of Hormuz, off

Iran's southern coast.)

The former senior intelligence official said

that the current contingency plans allow for an attack order this spring.

He added, however, that senior officers on the

Joint Chiefs were counting on the White House's not being,

"foolish enough to do this in

the face of Iraq, and the problems it would give the Republicans in

2008."

PRINCE BANDAR'S GAME

The Administration's effort to diminish Iranian authority in the Middle East

has relied heavily on Saudi Arabia and on Prince Bandar, the Saudi

national-security adviser.

Bandar served as the Ambassador to the United

States for twenty-two years, until 2005, and has maintained a friendship

with President Bush and Vice-President Cheney. In his new post, he continues

to meet privately with them.

Senior White House officials have made several

visits to Saudi Arabia recently, some of them not disclosed.

Last November, Cheney flew to Saudi Arabia for a surprise meeting with King

Abdullah and Bandar. The Times reported that the King warned Cheney that

Saudi Arabia would back its fellow-Sunnis in Iraq if the United States were

to withdraw. A European intelligence official told me that the meeting also

focused on more general Saudi fears about "the rise of the Shiites."

In response,

"The Saudis are starting to

use their leverage - money."

In a royal family rife with competition, Bandar

has, over the years, built a power base that relies largely on his close

relationship with the U.S., which is crucial to the Saudis.

Bandar was succeeded as Ambassador by Prince

Turki al-Faisal; Turki resigned after eighteen months and was replaced by

Adel A. al-Jubeir, a bureaucrat who has worked with Bandar.

A former Saudi diplomat told me that during

Turki's tenure he became aware of private meetings involving Bandar and

senior White House officials, including Cheney and Abrams.

"I assume Turki was not happy with that,"

the Saudi said. But, he added, "I don't think that Bandar is going off

on his own."

Although Turki dislikes Bandar, the Saudi said,

he shared his goal of challenging the spread of Shiite power in the Middle

East.

The split between Shiites and Sunnis goes back to a bitter divide, in the

seventh century, over who should succeed the Prophet Muhammad. Sunnis

dominated the medieval caliphate and the Ottoman Empire, and Shiites,

traditionally, have been regarded more as outsiders.

Worldwide, ninety per

cent of Muslims are Sunni, but Shiites are a majority in Iran, Iraq, and

Bahrain, and are the largest Muslim group in Lebanon.

Their concentration in a volatile, oil-rich

region has led to concern in the West and among Sunnis about the emergence

of a "Shiite crescent" - especially given Iran's increased geopolitical

weight.

"The Saudis still see the world through the

days of the Ottoman Empire, when Sunni Muslims ruled the roost and the

Shiites were the lowest class," Frederic Hof, a retired military officer

who is an expert on the Middle East, told me.

If Bandar was seen as bringing about a shift in

U.S. policy in favor of the Sunnis, he added, it would greatly enhance his

standing within the royal family.

The Saudis are driven by their fear that Iran could tilt the balance of

power not only in the region but within their own country. Saudi Arabia has

a significant Shiite minority in its Eastern Province, a region of major oil

fields; sectarian tensions are high in the province.

The royal family believes that Iranian

operatives, working with local Shiites, have been behind many terrorist

attacks inside the kingdom, according to Vali Nasr.

"Today, the only army capable of containing

Iran" - the Iraqi Army - "has been destroyed by the United States.

You're now dealing with an Iran that could be nuclear-capable and has a

standing army of four hundred and fifty thousand soldiers."

(Saudi Arabia has seventy-five thousand troops

in its standing army.)

Nasr went on,

"The Saudis have considerable financial

means, and have deep relations with the

Muslim Brotherhood and the

Salafis" - Sunni extremists who view Shiites as apostates.

"The last time Iran was a

threat, the Saudis were able to mobilize the worst kinds of Islamic

radicals. Once you get them out of the box, you can't put them back."

The Saudi royal family has been, by turns, both

a sponsor and a target of Sunni extremists, who object to the corruption and

decadence among the family's myriad princes.

The princes are gambling that they will not be

overthrown as long as they continue to support religious schools and

charities linked to the extremists. The Administration's new strategy is

heavily dependent on this bargain.

Nasr compared the current situation to the period in which Al Qaeda first

emerged. In the nineteen-eighties and the early nineties, the Saudi

government offered to subsidize the covert American C.I.A. proxy war against

the Soviet Union in Afghanistan.

Hundreds of young Saudis were sent into the

border areas of Pakistan, where they set up religious schools, training

bases, and recruiting facilities.

Then, as now, many of the operatives who were

paid with Saudi money were Salafis. Among them, of course, were Osama bin

Laden and his associates, who founded Al Qaeda, in 1988.

This time, the U.S. government consultant told me, Bandar and other Saudis

have assured the White House that,

"they will keep a very close eye on the

religious fundamentalists. Their message to us was,

'We've created this

movement, and we can control it.'

It's not that we don't want the Salafis to

throw bombs; it's who they throw them at - Hezbollah, Moqtada al-Sadr,

Iran, and at the Syrians, if they continue to work with Hezbollah and

Iran."

The Saudi said that, in his country's view, it

was taking a political risk by joining the U.S. in challenging Iran: Bandar

is already seen in the Arab world as being too close to the Bush

Administration.

"We have two nightmares," the former

diplomat told me.

"For Iran to acquire the bomb

and for the United States to attack Iran. I'd rather the Israelis bomb

the Iranians, so we can blame them. If America does it, we will be

blamed."

In the past year, the Saudis, the Israelis, and

the Bush Administration have developed a series of informal understandings

about their new strategic direction.

At least four main elements were involved, the

U.S. government consultant told me. First, Israel would be assured that its

security was paramount and that Washington and Saudi Arabia and other Sunni

states shared its concern about Iran.

Second, the Saudis would urge Hamas, the Islamist Palestinian party that has

received support from Iran, to curtail its anti-Israeli aggression and to

begin serious talks about sharing leadership with Fatah, the more secular

Palestinian group. (In February, the Saudis brokered a deal at Mecca between

the two factions.

However, Israel and the U.S. have expressed

dissatisfaction with the terms.)

The third component was that the Bush Administration would work directly

with Sunni nations to counteract Shiite ascendance in the region.

Fourth, the Saudi government, with Washington's approval, would provide

funds and logistical aid to weaken the government of President Bashir Assad,

of Syria. The Israelis believe that putting such pressure on the Assad

government will make it more conciliatory and open to negotiations. Syria is

a major conduit of arms to Hezbollah.

The Saudi government is also at odds with the

Syrians over the assassination of Rafik Hariri, the former Lebanese Prime

Minister, in Beirut in 2005, for which it believes the Assad government was

responsible. Hariri, a billionaire Sunni, was closely associated with the

Saudi regime and with Prince Bandar.

(A U.N. inquiry strongly suggested that the

Syrians were involved, but offered no direct evidence; there are plans for

another investigation, by an international tribunal.)

Patrick Clawson, of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, depicted

the Saudis' cooperation with the White House as a significant breakthrough.

"The Saudis understand that if they want the

Administration to make a more generous political offer to the

Palestinians they have to persuade the Arab states to make a more

generous offer to the Israelis," Clawson told me.

The new diplomatic approach, he added,

"shows a real degree of

effort and sophistication as well as a deftness of touch not always

associated with this Administration. Who's running the greater risk - we

or the Saudis? At a time when America's standing in the Middle East is

extremely low, the Saudis are actually embracing us. We should count our

blessings."

The Pentagon consultant had a different view.

He said that the Administration had turned to

Bandar as a "fallback," because it had realized that the failing war in Iraq

could leave the Middle East "up for grabs."

JIHADIS IN LEBANON

The focus of the U.S.-Saudi relationship, after Iran, is Lebanon, where the

Saudis have been deeply involved in efforts by the Administration to support

the Lebanese government.

Prime Minister Fouad Siniora is struggling to

stay in power against a persistent opposition led by Hezbollah, the Shiite

organization, and its leader, Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah.

Hezbollah has an extensive infrastructure, an

estimated two to three thousand active fighters, and thousands of additional

members.

Hezbollah has been on the State Department's terrorist list since 1997. The

organization has been implicated in the 1983 bombing of a Marine barracks in

Beirut that killed two hundred and forty-one military men. It has also been

accused of complicity in the kidnapping of Americans, including the C.I.A.

station chief in Lebanon, who died in captivity, and a Marine colonel

serving on a U.N. peacekeeping mission, who was killed.

(Nasrallah has denied that the group was

involved in these incidents.)

Nasrallah is seen by many as a staunch

terrorist, who has said that he regards Israel as a state that has no right

to exist. Many in the Arab world, however, especially Shiites, view him as a

resistance leader who withstood Israel in last summer's thirty-three-day

war, and Siniora as a weak politician who relies on America's support but

was unable to persuade President Bush to call for an end to the Israeli

bombing of Lebanon.

(Photographs of Siniora kissing Condoleezza Rice

on the cheek when she visited during the war were prominently displayed

during street protests in Beirut.)

The Bush Administration has publicly pledged the Siniora government a

billion dollars in aid since last summer.

A donors' conference in Paris, in January, which

the U.S. helped organize, yielded pledges of almost eight billion more,

including a promise of more than a billion from the Saudis. The American

pledge includes more than two hundred million dollars in military aid, and

forty million dollars for internal security.

The United States has also given clandestine support to the Siniora

government, according to the former senior intelligence official and the

U.S. government consultant.

"We are in a program to enhance the Sunni

capability to resist Shiite influence, and we're spreading the money

around as much as we can," the former senior intelligence official said.

The problem was that such money,

"always gets in more pockets than you think

it will," he said.

"In this process, we're

financing a lot of bad guys with some serious potential unintended

consequences. We don't have the ability to determine and get pay

vouchers signed by the people we like and avoid the people we don't

like. It's a very high-risk venture."

American, European, and Arab officials I spoke

to told me that the Siniora government and its allies had allowed some aid

to end up in the hands of emerging Sunni radical groups in northern Lebanon,

the Bekaa Valley, and around Palestinian refugee camps in the south.

These groups, though small, are seen as a buffer

to Hezbollah; at the same time, their ideological ties are with Al Qaeda.

During a conversation with me, the former Saudi diplomat accused Nasrallah

of attempting "to hijack the state," but he also objected to the Lebanese

and Saudi sponsorship of Sunni jihadists in Lebanon.

"Salafis are sick and hateful, and I'm very

much against the idea of flirting with them," he said. "They hate the

Shiites, but they hate Americans more. If you try to outsmart them, they

will outsmart us. It will be ugly."

Alastair Crooke, who spent nearly thirty years

in MI6, the British intelligence service, and now works for Conflicts Forum,

a think tank in Beirut, told me,

"The Lebanese government is

opening space for these people to come in. It could be very dangerous."

Crooke said that one Sunni extremist group,

Fatah al-Islam, had splintered from its pro-Syrian parent group, Fatah

al-Intifada, in the Nahr al-Bared refugee camp, in northern Lebanon.

Its membership at the time was less than two

hundred.

"I was told that within twenty-four hours

they were being offered weapons and money by people presenting

themselves as representatives of the Lebanese government's interests -

presumably to take on Hezbollah," Crooke said.

The largest of the groups, Asbat al-Ansar, is

situated in the Ain al-Hilweh Palestinian refugee camp.

Asbat al-Ansar has

received arms and supplies from Lebanese internal-security forces and

militias associated with the Siniora government.

In 2005, according to a report by the U.S.-based International Crisis Group,

Saad Hariri, the Sunni majority leader of the Lebanese parliament and the

son of the slain former Prime Minister - Saad inherited more than four

billion dollars after his father's assassination - paid forty-eight thousand

dollars in bail for four members of an Islamic militant group from Dinniyeh.

The men had been arrested while trying to

establish an Islamic mini-state in northern Lebanon. The Crisis Group noted

that many of the militants "had trained in al-Qaeda camps in Afghanistan."

According to the Crisis Group report, Saad Hariri later used his

parliamentary majority to obtain amnesty for twenty-two of the Dinniyeh

Islamists, as well as for seven militants suspected of plotting to bomb the

Italian and Ukrainian embassies in Beirut, the previous year.

(He also arranged a pardon for Samir Geagea, a

Maronite Christian militia leader, who had been convicted of four political

murders, including the assassination, in 1987, of Prime Minister Rashid

Karami.)

Hariri described his actions to reporters as

humanitarian.

In an interview in Beirut, a senior official in the Siniora government

acknowledged that there were Sunni jihadists operating inside Lebanon.

"We have a liberal attitude that allows Al

Qaeda types to have a presence here," he said.

He related this to concerns that Iran or Syria

might decide to turn Lebanon into a "theatre of conflict."

The official said that his government was in a no-win situation. Without a

political settlement with Hezbollah, he said, Lebanon could "slide into a

conflict," in which Hezbollah fought openly with Sunni forces, with

potentially horrific consequences.

But if Hezbollah agreed to a settlement yet

still maintained a separate army, allied with Iran and Syria,

"Lebanon could become a

target. In both cases, we become a target."

The Bush Administration has portrayed its

support of the Siniora government as an example of the President's belief in

democracy, and his desire to prevent other powers from interfering in

Lebanon.

When Hezbollah led street demonstrations in

Beirut in December, John Bolton, who was then the U.S. Ambassador to the

U.N., called them "part of the Iran-Syria-inspired coup."

Leslie H. Gelb, a past president of the

Council on Foreign Relations, said

that the Administration's policy was less pro democracy than,

"pro American national

security. The fact is that it would be terribly dangerous if Hezbollah

ran Lebanon."

The fall of the Siniora government would be

seen, Gelb said,

"as a signal in the Middle

East of the decline of the United States and the ascendancy of the

terrorism threat. And so any change in the distribution of political

power in Lebanon has to be opposed by the United States - and we're

justified in helping any non-Shiite parties resist that change. We

should say this publicly, instead of talking about democracy."

Martin Indyk, of the Saban Center, said,

however, that the United States,

"does not have enough pull to

stop the moderates in Lebanon from dealing with the extremists."

He added,

"The President sees the region as divided

between moderates and extremists, but our regional friends see it as

divided between Sunnis and Shia. The Sunnis that we view as extremists

are regarded by our Sunni allies simply as Sunnis."

In January, after an outburst of street violence

in Beirut involving supporters of both the Siniora government and Hezbollah,

Prince Bandar flew to Tehran to discuss the political impasse in Lebanon and

to meet with Ali Larijani, the Iranians' negotiator on nuclear issues.

According to a Middle Eastern ambassador,

Bandar's mission - which the ambassador said was endorsed by the White House

- also aimed "to create problems between the Iranians and Syria."

There had been tensions between the two

countries about Syrian talks with Israel, and the Saudis' goal was to

encourage a breach.

However, the ambassador said,

"It did not work. Syria and

Iran are not going to betray each other. Bandar's approach is very

unlikely to succeed."

Walid Jumblatt, who is the leader of the Druze

minority in Lebanon and a strong Siniora supporter, has attacked Nasrallah

as an agent of Syria, and has repeatedly told foreign journalists that

Hezbollah is under the direct control of the religious leadership in Iran.

In a conversation with me last December, he

depicted Bashir Assad, the Syrian President, as a "serial killer." Nasrallah,

he said, was "morally guilty" of the assassination of Rafik Hariri and the

murder, last November, of Pierre Gemayel, a member of the Siniora Cabinet,

because of his support for the Syrians.

Jumblatt then told me that he had met with Vice-President Cheney in

Washington last fall to discuss, among other issues, the possibility of

undermining Assad.

He and his colleagues advised Cheney that, if

the United States does try to move against Syria, members of the Syrian

Muslim Brotherhood would be "the ones to talk to," Jumblatt said.

The Syrian Muslim Brotherhood, a branch of a radical Sunni movement founded

in Egypt in 1928, engaged in more than a decade of violent opposition to the

regime of Hafez Assad, Bashir's father. In 1982, the Brotherhood took

control of the city of Hama; Assad bombarded the city for a week, killing

between six thousand and twenty thousand people.

Membership in the Brotherhood is punishable by

death in Syria. The Brotherhood is also an avowed enemy of the U.S. and of

Israel.

Nevertheless, Jumblatt said,

"We told Cheney that the

basic link between Iran and Lebanon is Syria - and to weaken Iran you

need to open the door to effective Syrian opposition."

There is evidence that the Administration's

redirection strategy has already benefitted the Brotherhood.

The Syrian National Salvation Front is a

coalition of opposition groups whose principal members are a faction led by

Abdul Halim Khaddam, a former Syrian Vice-President who defected in 2005,

and the Brotherhood.

A former high-ranking C.I.A. officer told me,

"The Americans have provided

both political and financial support. The Saudis are taking the lead

with financial support, but there is American involvement."

He said that Khaddam, who now lives in Paris,

was getting money from Saudi Arabia, with the knowledge of the White House.

(In 2005, a delegation of the Front's members

met with officials from the National Security Council, according to press

reports.) A former White House official told me that the Saudis had provided

members of the Front with travel documents.

Jumblatt said he understood that the issue was a sensitive one for the White

House.

"I told Cheney that some people in the Arab

world, mainly the Egyptians" - whose moderate Sunni leadership has been

fighting the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood for decades - "won't like it if

the United States helps the Brotherhood. But if you don't take on Syria

we will be face to face in Lebanon with Hezbollah in a long fight, and

one we might not win."

THE SHEIKH

On a warm, clear night early last December, in a bombed-out suburb a few

miles south of downtown Beirut, I got a preview of how the Administration's

new strategy might play out in Lebanon.

Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah, the Hezbollah leader,

who has been in hiding, had agreed to an interview. Security arrangements

for the meeting were secretive and elaborate. I was driven, in the back seat

of a darkened car, to a damaged underground garage somewhere in Beirut,

searched with a handheld scanner, placed in a second car to be driven to yet

another bomb-scarred underground garage, and transferred again.

Last summer, it was reported that Israel was

trying to kill Nasrallah, but the extraordinary precautions were not due

only to that threat.

Nasrallah's aides told me that they believe he

is a prime target of fellow-Arabs, primarily Jordanian intelligence

operatives, as well as Sunni jihadists who they believe are affiliated with

Al Qaeda.

(The government consultant and a retired

four-star general said that Jordanian intelligence, with support from the

U.S. and Israel, had been trying to infiltrate Shiite groups, to work

against Hezbollah. Jordan's King Abdullah II has warned that a Shiite

government in Iraq that was close to Iran would lead to the emergence of a

Shiite crescent.)

This is something of an ironic turn: Nasrallah's

battle with Israel last summer turned him - a Shiite - into the most popular

and influential figure among Sunnis and Shiites throughout the region. In

recent months, however, he has increasingly been seen by many Sunnis not as

a symbol of Arab unity but as a participant in a sectarian war.

Nasrallah, dressed, as usual, in religious garb, was waiting for me in an

unremarkable apartment.

One of his advisers said that he was not likely

to remain there overnight; he has been on the move since his decision, last

July, to order the kidnapping of two Israeli soldiers in a cross-border raid

set off the thirty-three-day war.

Nasrallah has since said publicly - and repeated

to me - that he misjudged the Israeli response.

"We just wanted to capture prisoners for

exchange purposes," he told me. "We never wanted to drag the region into

war."

Nasrallah accused the Bush Administration of

working with Israel to deliberately instigate fitna, an Arabic word that is

used to mean "insurrection and fragmentation within Islam."

"In my opinion, there is a huge campaign

through the media throughout the world to put each side up against the

other," he said. "I believe that all this is being run by American and

Israeli intelligence."

(He did not provide any specific evidence for

this.)

He said that the U.S. war in Iraq had increased

sectarian tensions, but argued that Hezbollah had tried to prevent them from

spreading into Lebanon. (Sunni-Shiite confrontations increased, along with

violence, in the weeks after we talked.)

Nasrallah said he believed that President Bush's goal was,

"the drawing of a new map for the region.

They want the partition of Iraq. Iraq is not on the edge of a civil war

- there is a civil war. There is ethnic and sectarian cleansing.

The daily killing and displacement which is

taking place in Iraq aims at achieving three Iraqi parts, which will be

sectarian and ethnically pure as a prelude to the partition of Iraq.

Within one or two years at the most, there will be total Sunni areas,

total Shiite areas, and total Kurdish areas.

Even in Baghdad, there is a

fear that it might be divided into two areas, one Sunni and one Shiite."

He went on,

"I can say that President

Bush is lying when he says he does not want Iraq to be partitioned. All

the facts occurring now on the ground make you swear he is dragging Iraq

to partition. And a day will come when he will say, 'I cannot do

anything, since the Iraqis want the partition of their country and I

honor the wishes of the people of Iraq.' "

Nasrallah said he believed that America also

wanted to bring about the partition of Lebanon and of Syria.

In Syria, he said, the result would be to push

the country,

"into chaos and internal

battles like in Iraq."

In Lebanon,

"There will be a Sunni state, an Alawi

state, a Christian state, and a Druze state."

But, he said,

"I do not know if there will

be a Shiite state."

Nasrallah told me that he suspected that one aim

of the Israeli bombing of Lebanon last summer was,

"the destruction of Shiite areas and the

displacement of Shiites from Lebanon. The idea was to have the Shiites

of Lebanon and Syria flee to southern Iraq," which is dominated by

Shiites.

"I am not sure, but I smell this," he told

me.

Partition would leave Israel surrounded by,

"small tranquil states," he said.

"I can assure you that the Saudi kingdom

will also be divided, and the issue will reach to North African states.

There will be small ethnic and confessional states," he said.

"In other words, Israel will

be the most important and the strongest state in a region that has been

partitioned into ethnic and confessional states that are in agreement

with each other. This is the new Middle East."

In fact, the Bush Administration has adamantly

resisted talk of partitioning Iraq, and its public stances suggest that the

White House sees a future Lebanon that is intact, with a weak, disarmed

Hezbollah playing, at most, a minor political role.

There is also no evidence to support Nasrallah's

belief that the Israelis were seeking to drive the Shiites into southern

Iraq. Nevertheless, Nasrallah's vision of a larger sectarian conflict in

which the United States is implicated suggests a possible consequence of the

White House's new strategy.

In the interview, Nasrallah made mollifying gestures and promises that would

likely be met with skepticism by his opponents.

"If the United States says that discussions

with the likes of us can be useful and influential in determining

American policy in the region, we have no objection to talks or

meetings," he said.

"But, if their aim through

this meeting is to impose their policy on us, it will be a waste of

time."

He said that the Hezbollah militia, unless

attacked, would operate only within the borders of Lebanon, and pledged to

disarm it when the Lebanese Army was able to stand up.

Nasrallah said that he had no interest in

initiating another war with Israel. However, he added that he was

anticipating, and preparing for, another Israeli attack, later this year.

Nasrallah further insisted that the street demonstrations in Beirut would

continue until the Siniora government fell or met his coalition's political

demands.

"Practically speaking, this government

cannot rule," he told me. "It might issue orders, but the majority of

the Lebanese people will not abide and will not recognize the legitimacy

of this government. Siniora remains in office because of international

support, but this does not mean that Siniora can rule Lebanon."

President Bush's repeated praise of the Siniora

government, Nasrallah said,

"is the best service to the

Lebanese opposition he can give, because it weakens their position

vis-à-vis the Lebanese people and the Arab and Islamic populations. They

are betting on us getting tired. We did not get tired during the war, so

how could we get tired in a demonstration?"

There is sharp division inside and outside the

Bush Administration about how best to deal with Nasrallah, and whether he

could, in fact, be a partner in a political settlement.

The outgoing director of National Intelligence,

John Negroponte, in a farewell briefing to the Senate Intelligence

Committee, in January, said that Hezbollah,

"lies at the center of Iran's

terrorist strategy... It could decide to conduct attacks against U.S.

interests in the event it feels its survival or that of Iran is

threatened... Lebanese Hezbollah sees itself as Tehran's partner."

In 2002,

Richard Armitage, then the Deputy

Secretary of State, called Hezbollah,

"the A-team" of terrorists.

In a recent interview, however, Armitage

acknowledged that the issue has become somewhat more complicated.

Nasrallah, Armitage told me, has emerged as,

"a political force of some

note, with a political role to play inside Lebanon if he chooses to do

so."

In terms of public relations and political

gamesmanship, Armitage said, Nasrallah,

"is the smartest man in the Middle East."

But, he added, Nasrallah "has got to make it clear that he wants to play

an appropriate role as the loyal opposition. For me, there's still a

blood debt to pay" - a reference to the murdered colonel and the Marine

barracks bombing.

Robert Baer, a former longtime C.I.A. agent in

Lebanon, has been a severe critic of Hezbollah and has warned of its links

to Iranian-sponsored terrorism.

But now, he told me, "we've got Sunni Arabs

preparing for cataclysmic conflict, and we will need somebody to protect the

Christians in Lebanon. It used to be the French and the United States who

would do it, and now it's going to be Nasrallah and the Shiites.

"The most important story in the Middle East

is the growth of Nasrallah from a street guy to a leader - from a

terrorist to a statesman," Baer added.

"The dog that didn't bark this summer" -

during the war with Israel - "is Shiite terrorism."

Baer was referring to fears that Nasrallah, in

addition to firing rockets into Israel and kidnapping its soldiers, might

set in motion a wave of terror attacks on Israeli and American targets

around the world.

"He could have pulled the trigger, but he

did not," Baer said.

Most members of the intelligence and diplomatic

communities acknowledge Hezbollah's ongoing ties to Iran.

But there is disagreement about the extent to

which Nasrallah would put aside Hezbollah's interests in favor of Iran's. A

former C.I.A. officer who also served in Lebanon called Nasrallah,

"a Lebanese phenomenon," adding,

"Yes, he's aided by Iran and Syria, but Hezbollah's gone beyond that."

He told me that there was a period in the late

eighties and early nineties when the C.I.A. station in Beirut was able to

clandestinely monitor Nasrallah's conversations.

He described Nasrallah as,

"a gang leader who was able

to make deals with the other gangs. He had contacts with everybody."

TELLING CONGRESS

The Bush Administration's reliance on clandestine operations that have not

been reported to Congress and its dealings with intermediaries with

questionable agendas have recalled, for some in Washington, an earlier

chapter in history.

Two decades ago, the Reagan Administration

attempted to fund the Nicaraguan contras illegally, with the help of secret

arms sales to Iran. Saudi money was involved in what became known as the

Iran-Contra scandal, and a few of the players back then - notably Prince

Bandar and Elliott Abrams - are involved in today's dealings.

Iran-Contra was the subject of an informal "lessons learned" discussion two

years ago among veterans of the scandal. Abrams led the discussion. One conclusion was that even though the program

was eventually exposed, it had been possible to execute it without telling

Congress.

As to what the experience taught them, in terms of future covert

operations, the participants found:

"One, you can't trust our friends. Two, the C.I.A. has got to be totally out of it. Three, you can't trust the

uniformed military, and four, it's got to be run out of the

Vice-President's office" - a reference to Cheney's role, the former

senior intelligence official said.

I was subsequently told by the two government

consultants and the former senior intelligence official that the echoes of

Iran-Contra were a factor in Negroponte's decision to resign from the

National Intelligence directorship and accept a sub-Cabinet position of

Deputy Secretary of State. (Negroponte declined to comment.)

The former senior intelligence official also told me that Negroponte did not

want a repeat of his experience in the Reagan Administration, when he served

as Ambassador to Honduras.

"Negroponte said, 'No way. I'm not going

down that road again, with the N.S.C. running operations off the books,

with no finding.' "

(In the case of covert C.I.A. operations, the

President must issue a written finding and inform Congress.)

Negroponte stayed on as Deputy Secretary of

State, he added, because,

"he believes he can influence

the government in a positive way."

The government consultant said that Negroponte

shared the White House's policy goals but "wanted to do it by the book."

The Pentagon consultant also told me that,

"there was a sense at the

senior-ranks level that he wasn't fully on board with the more

adventurous clandestine initiatives."

It was also true, he said, that Negroponte,

"had problems with this Rube

Goldberg policy contraption for fixing the Middle East."

The Pentagon consultant added that one

difficulty, in terms of oversight, was accounting for covert funds.

"There are many, many pots of black money,

scattered in many places and used all over the world on a variety of

missions," he said.

The budgetary chaos in Iraq, where billions of

dollars are unaccounted for, has made it a vehicle for such transactions,

according to the former senior intelligence official and the retired

four-star general.

"This goes back to Iran-Contra," a former

National Security Council aide told me. "And much of what they're doing

is to keep the agency out of it."

He said that Congress was not being briefed on

the full extent of the U.S.-Saudi operations.

And, he said,

"The C.I.A. is asking,

'What's going on?' They're concerned, because they think it's amateur

hour."

The issue of oversight is beginning to get more

attention from Congress.

Last November, the Congressional Research

Service issued a report for Congress on what it depicted as the

Administration's blurring of the line between C.I.A. activities and strictly

military ones, which do not have the same reporting requirements.

And the

Senate Intelligence Committee, headed by Senator Jay Rockefeller, has

scheduled a hearing for March 8th on Defense Department intelligence

activities.

Senator Ron Wyden, of Oregon, a Democrat who is a member of the Intelligence

Committee, told me,

"The Bush Administration has

frequently failed to meet its legal obligation to keep the Intelligence

Committee fully and currently informed. Time and again, the answer has

been 'Trust us.' "

Wyden said,

"It is hard for me to trust

the Administration."